Most of Intel's announcements lately have focused on low-power chips, but every now and again it throws a bone to its high-end desktop users. Today we're getting our first look at Haswell-E and a new Core i7 Extreme Edition CPU, a moniker reserved for the biggest and fastest of Intel's consumer and workstation CPUs (if you want something faster than that, you'll need to start looking at Xeons).

We already got a little bit of information on these chips back in March, when Intel made announcements related to refreshed Haswell chips ("Devil's Canyon") and a handful of other desktop processors. Though much of today's information has already leaked, we'll run down the most important stuff for those of you who don't follow every leaked slide that makes its way to the public.

The CPUs

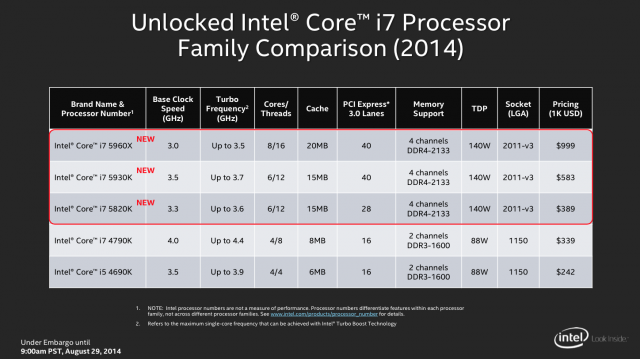

Intel is announcing three new chips today, the specifications for which have all leaked at this point. There are two six-core processors: the first is the $389 Core i7-5820K, which runs at 3.3GHz and Turbo Boosts up to 3.6GHz. The second is the $583 i7-5930K, which runs at 3.5GHz and Turbo Boosts to 3.7GHz. Both include HyperThreading, 15MB of L3 cache, and the same 140W TDP. The main difference aside from clock speed is that the i7-5820K only includes 28 PCI Express 3.0 lanes instead of 40. This is still more than the 16 lanes you'll get with quad-core desktop CPUs, but if you want a multi-card gaming rig the lower-end CPU may not be for you (otherwise it offers by far the best cost-to-performance ratio of any of these chips).

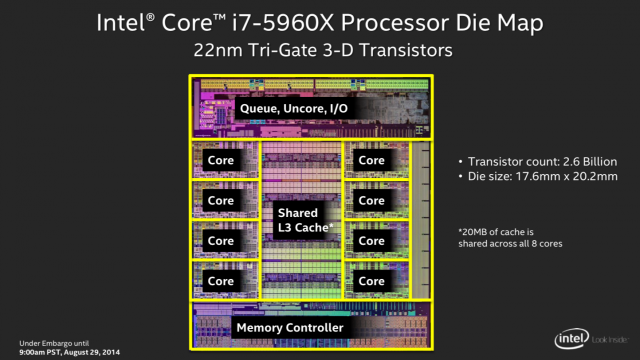

Six-core chips were top-of-the-line in the Sandy Bridge and Ivy Bridge-E families, but Haswell-E adds more in the eight-core i7-5960X, a $999 CPU with a 3.0GHz clock speed, a 3.5GHz Turbo Boost speed, and 20MB of cache. In the Sandy and Ivy Bridge families, you'd need to step up to EP or EX-class Xeon chips—some workstation manufacturers did just that, with the new Mac Pro being just one prominent example.

The caveat with these chips are the same as they are for any CPU that adds cores to add speed: you really need to have a heavily multi-threaded workload to take advantage of the extra cores. Intel's own slide deck focuses on workloads that benefit from this kind of thing—video editing, 3D rendering, and physics calculations. Intel estimates that the eight-core Haswell-E chip can covert video in Handbrake "up to 34 percent faster" than a six-core Ivy Bridge-E chip and "up to 69 percent faster" than a standard quad-core Ivy Bridge desktop chip (the i7-4790K, in this case.) For single-threaded or lightly-multithreaded tasks, you'll actually lose a little bit of clock speed here compared to Intel's top-end quad-core chips, so evaluate your workload carefully before you pull the trigger.

There's also a benefit for people who are doing GPU-intensive work, since 40 PCI Express 3.0 lanes can support up to three graphics cards all by themselves (two would have access to a full 16 lanes, while one would be restricted to eight). With additional components, you could add up to five GPUs (each with access to eight lanes.) Finally, all three CPUs come unlocked, so adventurous overclockers can try to squeeze a bit more performance out of them, though the regular Haswell platform hasn't exactly been known for its overclockability.

The other stuff

In addition to the information about the chips themselves, here's what you need to know about the associated motherboards, sockets, and chipsets.

Haswell-E brings with it another version of the LGA 2011 socket used for other high-end CPUs. The original LGA 2011 is used for Sandy Bridge and Ivy Bridge E and EP parts, and LGA 2011 v1 sockets were required for top-end Ivy Bridge-EX CPUs. Haswell-E uses LGA 2011 v3. As with the jump from Ivy Bridge to Haswell on consumer desktops, Ivy Bridge-E and Haswell-E parts won't be pin-compatible. We expect the majority of Ivy Bridge-E users aren't going to be upgrading these systems every single year anyway, but it's something new buyers should keep in mind as they piece together components.

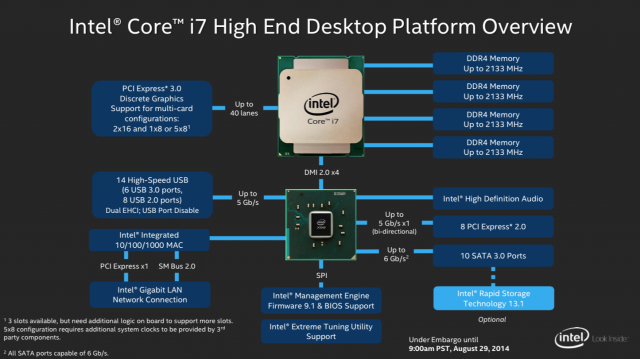

And speaking of new components, upgraders will need to throw out their DDR3 memory, too: Haswell-E is Intel's first platform to integrate support for DDR4 RAM, which we first wrote about back in 2012. Like DDR2 and DDR3 before it, DDR4 reduces voltage while increasing speeds—you step down from 1.5V of power to 1.2V, and step up from 1866MHz to 2133MHz (though increased latency may eat up some of these gains). DDR4 is already available in faster speeds and will continue to pull away from DDR3 as the technology matures, but that's the fastest speed supported by Intel's new platform as of this writing. Both the Haswell-E and Ivy Bridge-E platforms support quad-channel memory, where most desktops still use dual-channel.

DDR4 will come with a bit of a price premium over DDR3, but at the rated clock speeds it's not too big of a hit: a glance at Newegg shows 8GB sticks of DDR3-1866 starting at $82 and sticks of DDR4-2133 starting at $110. That's an increase of around a third, though if you're already putting down the money for the CPU and the motherboard it's probably not enough to make you flinch.

Finally, the glue that holds all of these parts together is Intel's X99 chipset, which supports most of the same features as the more down-to-earth Z97 and H97 chipsets announced earlier this year. The platform supports a total of 14 USB ports (six USB 3.0 ports), an Intel gigabit Ethernet port, eight additional PCI Express 2.0 lanes, integrated audio support, and a total of 10 SATA III ports. Unlike the Ivy Bridge-E platform, Haswell-E is able to support Thunderbolt 2.0, but your motherboard manufacturer will still need to integrate the dedicated controller to make that happen.

Intel has a lengthy list of partners lined up for the Haswell-E launch, including complete system builders like Alienware, Falcon Northwest, and CyberpowerPC; and motherboard makers like Gigabyte, Asus, and MSI. Intel can usually drum up plenty of industry support for its new platforms, so this isn't much of a surprise.

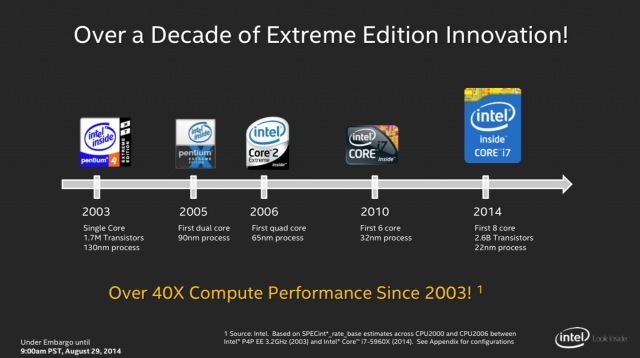

All in all it looks like a reasonably compelling update to Intel's high-end workstation platform, though anyone still happy with their Sandy Bridge and Ivy Bridge-E setups won't need to run out to upgrade right away. This slide from Intel drives it home pretty well:

The desktop space between 2003 and 2006 experienced a flurry of growth, going from the hot single-core Pentium 4 Extreme Edition to the quad-core Core 2 Extreme CPU. In those three years, Intel increased its chips' instructions-per-clock, their core counts, and their power consumption. The quad-core CPU has a TDP of 130W, just 15W higher than the single-core Pentium 4. The improvements came more quickly, and they were easier to demonstrate.

The four years between the Core 2 Extreme and the first six-core i7 chip look a lot quieter by comparison, not least because the late 2000s and early 2010s saw a big shift away from the desktop in the direction of mobile. Improving top-end performance was still important and it still increases year-to-year, but power consumption is the larger concern. A similar four-year gap separates the six-core Extreme Edition and today's eight-core version. The high-end desktop platform still improves every year; it's just more difficult to tell the difference between last year's performance and this year's than it was a decade ago.

Listing image by Intel

reader comments

119