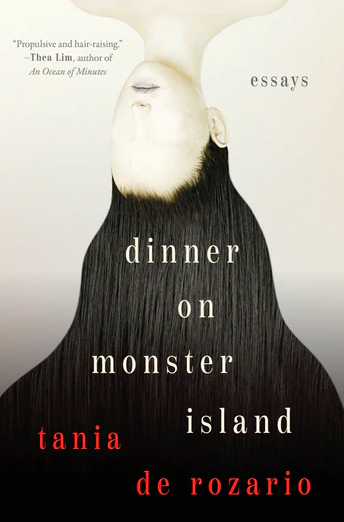

essays

The Monsters We Fear Tells Us Something Essential About Who We Are

I needed to understand why watching "The Ring" filled me with terror in a way no other villain ever had

1998. Lido Cineplex. Cold air, soft seats, the smell of popcorn. My friend Alice and I are both 17 years old and this is the quietest we’ve ever been together.

The audience too has been silent for the last ninety minutes. No whispers, no beeping pagers, no awkward laughter at inappropriate moments. The air is thick with tension. Even the walls are afraid to breathe.

On-screen, a man’s television set switches itself on. Static-ridden footage of an old brick well appears. A woman slowly emerges from it, her waist-length hair black, wet, and shrouding her face. Her long white dress hangs off her disjointed frame. She pulls herself out of the well and makes her way towards the camera. She moves slowly, painfully, hobbling from so many broken bones. Her movements seem unnatural, wrong. The closer she gets to the inside of the screen, the more we’re unsure of how this will end. And then, when she is as close as she can get, she pushes herself through the television screen, into his living room.

It is clear he is going to die. The cinema erupts into screams.

That was the first time I met Sadako Yamamura. The day she found her way into that man’s living room, she found her way into my flesh. The movie ended at 1:00 a.m. Alice came out of the cinema shaking. During the film’s climax, she had rolled herself into a ball and used God’s name in vain a thousand different ways. My own terror, more silent, haunted me persistently for weeks after.

It’s not like I have no tolerance for horror. By the time I met Sadako, I’d gorged my fill of Freddy Kruegers and Chucky dolls—anything Hollywood had to offer that friends could sneak past Singapore censors. Horror, to me, was a subset of comedy—funny, but for all the wrong reasons: the blood that looked inevitably fake, the groan-inducing jump scares, the stop-motion effects that always felt a step out of sync. In fact, we’d ended up watching Hideo Nakata’s Ringu that night precisely because the comedy we’d been planning on seeing was sold out. Internet booking didn’t exist yet and as fate had it, all that was available was some obscure Japanese film that neither of us had heard of.

What I had anticipated when we booked those tickets were jump scares, over-the-top effects, and cheesy music. What I got instead were long silences, vague segues, and lots of unanswered questions. Like Sadako herself, this film did not care for lengthy explanations or audience expectations. The only thing left unambiguous was Sadako’s rage—murderous, indiscriminate, everlasting.

That night, Alice begged me to stay over at her house, as I’d done so many times before. There was a television in her bedroom and she needed company.

I would have, except the first person to die in this movie was a girl at a sleepover.

Sadako taught me that there are limits even to friendship.

A woman slowly emerges, her waist-length hair black, wet, and shrouding her face. She pulls herself out of the well and makes her way towards the camera.

The week after my first encounter with Sadako, I returned to the cinema to watch Ringu again, thinking it would alleviate my fear. In actuality, the only thing this second viewing did was bring my attention to all the terrifying details I’d missed before. Thinking that perhaps the third time would make it better, I returned yet again. With everything I’d missed now magnified, I was high on terror and had to live with the side effects of my bad decisions. Back home, I jumped every time the phone rang. I prickled at every sound that even vaguely resembled static. I avoided looking at reflective surfaces.

It should have been clear to me that there was something besides being a sucker for pain that kept drawing me back into the cinema. Some strange kinship I felt with Sadako. I’d understand in years to come that I’d been investigating my own fear, wanting to know what it was about her that filled me with terror in a way no other movie villain ever had. Even later in life, I would understand that this is where my fascination with monsters—how we create them, why we create them, how what we fear says something about who we are—surfaced into consciousness.

But it would take many a horror movie more for me to make that leap. For the time being, all I knew was that I was swearing off television.

Over two decades since its first release, Ringu arguably remains the film that launched Japanese horror cinema into the international spotlight, spawning one Hollywood remake after another. By the mid- 2000s, South Korean horror and Thai horror had followed suit, and it was through these films that I eventually found my way back to Sadako.

You see, Sadako was a trendsetter. In almost every Asian horror film that made it big after Ringu there lingered a female ghost with long black hair and a long white dress, lurking in some celluloid corner. But watch enough horror from across Asia and you’ll see an even deeper pattern emerge:

In Japan’s Ju-On, Kayako haunts the house in which she and her child were murdered by her husband. In South Korea’s Phone, a woman is haunted by the ghost of the mistress her husband has killed. In Singapore’s The Maid, a domestic worker murdered by her employers returns to avenge her death.

Women being killed. Women refusing to die.

Something kept drawing me back into the cinema. Some strange kinship I felt with Sadako.

I could not bring myself to watch Ringu again, but I plowed through many other films, looking for language for my obsession. And finally, it was Natre, the ghost from Thailand’s Shutter, that taught me why Sadako kept calling me back.

In Shutter, Natre, who disappeared from her college many years before, returns to haunt her ex-boyfriend, Tun, through his photography. She appears in his prints. She materializes in developing solution. She rises from his darkroom sink, which overflows with water. At this point, I have already sworn off television, and as I sit through Shutter, I am pretty sure I am never taking another photograph again.

However, towards the end of the film, something inside me shifts. It is revealed through a flashback that Natre died by suicide. She had been raped by a schoolmate while Tun stood by, watched, and took a photo of the ordeal with the camera she had given him for his birthday. The scene is merciless and I find myself sobbing, brutalized by the sheer reality of it. By the time this information is revealed to us, Natre’s ghost has already driven all the men involved to suicide, while Tun awaits the same fate.

In the film’s climax, Tun stands alone in his apartment, yelling at the air, demanding Natre reveal herself. He takes multiple photos of his empty room with a Polaroid camera, hoping she will appear in the photographs. He does it manically, ridden with anxiety, finally throwing the camera to the floor in frustration when she does not oblige.

It is then that we hear the click of the shutter. A photo emerges. He walks towards the camera, pulls out the picture, and alongside him, we watch it develop. In it, we see him standing. And on his shoulders, like the weight of guilt, sits Natre. Her arms engulf him in a lover’s embrace. He throws the camera to the floor again and struggles to get her off him. But she is persistent and won’t let go. The last we see of him, she is covering his eyes as he stumbles blind through the apartment, eventually tumbling off the ledge of his balcony.

This is where my fascination with monsters—how and why we create them, how what we fear says something about who we are—surfaced into consciousness.The audience screams, and I scream too. Except I find that I am screaming “Yes!” I realize immediately that I’ve changed sides. To me, this is not a plot twist—it is an exercise in victory. Natre, Sadako, all these women—they were victims, not villains. And they’d found a way to survive.

These stories weren’t about seeking revenge. They were about dispensing justice.

Watch enough horror from across Asia and you’ll see an even deeper pattern emerge: Women being killed. Women refusing to die.

Sadako, like her avenging counterparts, treads a thin line between agency and oppression. On the one hand, she is a powerful figure seeking justice on her own terms. On the other, she is only allowed agency in death. The narrative may not have been intended as commentary, but like all film and television, once it is out in the world, it is subject to the context of the world. Sadako is a woman, but also a monster—a heightened version of us dishing out punishment upon a world in which violence against women and people of all marginalized genders often goes unpunished.

This is how Sadako comes into her own: born with psychic powers that her family does not know how to handle. Her father pushes her into a well, leaving her there to die. She remains alive for seven days, hopeless, scared, angry enough for her rage to manifest as a curse, inscribing itself onto a videotape housed in a cabin nearby. The tape sits unmarked, waiting for someone to watch it. Watch it, and you will receive a phone call filled with static, and in seven days, you will die too. She will rise before you, wherever you are, and look upon you from between locks of matted hair. Her mere gaze will cause your heart to stop.

Sadako’s is a story of feminine rage but also a testimony to how that rage has withstood the test of time. Sadako may have crawled her way onscreen in the nineties, but in truth, she is a contemporary expression of a much older archetype. While Hideo Nakata’s Ringu is based on Koji Suzuki’s 1991 novel of the same name, the film’s visual portrayal of Sadako is a clear homage to Oiwa, the vengeful spirit from Yotsuya Kaiden, a famous Japanese ghost story. Written in 1825 as a Kabuki play, it has been restaged across decades, and adapted into film and puppetry numerous times over.

The most obvious allusions to Oiwa are found in two of Ringu’s key scenes. The first is the climax, in which Sadako crawls out of the television set. In Yotsuya Kaidan, Oiwa emerges from a lantern—another object illuminated from within—in a moment so iconic to Japanese storytelling, it has been immortalized in woodblock prints now considered indispensable to Japan’s cultural history.

The second is found in Sadako’s iconic murderous glare, characterized by the camera closing in on a single, bloodshot eye. This references the poison that Oiwa was given by her husband, which injured her left eye, causing it to droop.

These stories weren’t about seeking revenge. They were about dispensing justice.

I’ve always loved how Sadako took the source of Oiwa’s impairment and turned it into the center of her power—the bloodshot eye, still drooping, that can kill with a single glance.

There is always so much talk about the male gaze. Imagine if this was what happened every time the rest of us gazed back.

Like Sadako and all her on-screen sisters, the ghost of Oiwa is not alone in her mythology. Asia, despite its myriad diversity, is fraught, across borders, with feminine monstrosity.

In Indonesia, the Sundel Bolong’s sexual appetites in life result in her perpetual appetite in death. No matter what she eats, it falls out of her stomach through a hole in her back so that she is never full, always hungry, always wanting.

In Japan, the Ubume stands in the pouring rain, infant in arms. She asks you to help her carry her baby. Gallant, you take it, and she disappears. The baby gets heavier and heavier, until you are eventually crushed under its weight.

In India, the Churel tricks you into her lair. You don’t realize that her feet are turned backwards. So when you see her footprints, you run in the opposite direction. Eventually you see her, waiting for you, her teeth sharp, your life short.

In Singapore, we grew up with the Pontianak—the ghost of a woman who dies in childbirth and seeks out revenge in the afterlife. While she originates in Malaysia (and her sister, the Kuntilanak, in Indonesia), versions of her exist in numerous countries across the continent. These women all have different names, but share a broad origin story that is remarkably similar—death in childbirth. In the original folklore, the Pontianak is said to seek out pregnant women or virgin girls whose bodily fluids she consumes. Today, she seeks out men, walking the streets at night by herself. Her pale skin and long dark hair are the epitome of Asian beauty standards, and she seduces these men with ease before transforming into a long-clawed monster who digs into their stomachs and feasts on their insides.

Sadako treads a thin line between agency and oppression. She is a powerful figure seeking justice on her own terms, but she is only allowed agency in death.

I can’t help but notice that in the older stories, written by men, she comes across as a cautionary tale for women, but in newer permutations, written by women, she issues warnings for men to heed: This body is not yours. This flesh is not yours. Beauty not as invitation, but as warning.

Sadako’s cursed videotape comprises several images. These include distorted figures crawling from sea to shore, text that dances across the screen, a strange hooded, pointing figure.

But the image that lingers most in collective imagination is the scene of Sadako’s young mother, looking into a mirror and slowly combing her hair. As you watch her, she notices you. Her mouth curls into a slow, deliberate smile, and she turns to meet your gaze.

Hair—usually long, black, and unruly—is a common motif in Asian horror. It pours out of faucets in deep, dark waves. It descends from the ceiling like a noose. It clogs drains and pipes, blankets children in their sleep, floats limp in cups of tea.

Historically, and as in many other cultures, hair functioned as a mark of status in Japan. The higher in status you were, the more elaborately structured and adorned your hair was likely to be.

For women in particular, hair held additional meaning; it spoke of moral purity. While long and luxurious hair was the epitome of beauty, women seen in public with their hair down were perceived to have “loose” morals or to be “mentally unsound.” In her essay “It’s Alive: Disorderly and Dangerous Hair in Japanese Horror Cinema,” academic Colette Balmain mentions how in households where wives and mistresses lived together, it was believed that jealousy between women took shape in their hair at night, turning strands into serpents that attacked one another while the women themselves slept. Consequently, we might conclude that keeping one’s hair pinned meant keeping the peace. The only time it was culturally acceptable for a woman to have her hair down in front of others was during burial rituals, when she was dead.

Natre, Sadako, all these women—they were victims, not villains. And they’d found a way to survive.

The scene of hair being brushed in Sadako’s video is no accident. In Kabuki theater, extended scenes of hair brushing were once erotically charged. It was in fact an adaptation of Yotsuya Kaidan that became the first piece of Kabuki theater to interrogate this trope.

In the adaptation, Oiwa sits onstage, brushing her hair. But because she has been poisoned, it falls out as she brushes it. Beneath the stage, stagehands pile prop hair onto the floor in front of her from a trapdoor on the stage. Bit by bit, the pile grows thick and grotesque—an abject mass that appears seemingly out of nowhere.

In Ringu, Sadako’s hair too is iconic. It covers her face for most of the film, and is pushed back only when her remains are dug up from the well. When we see her bones emerge, a thick swelling of hair slips off the wet surface of her skull, and sinks into the sludge. Like the well water, it is perfect black—night, coal, sleep, expired stars.

One of Japan’s most famous wells is located on the periphery of Himeji Castle, where a young servant girl named Okiku is said to have lived and worked. In one version of the story, a samurai who was both besotted with and rejected by her, decided to get revenge for her lack of reciprocity. He hid one of the king’s plates, knowing she would be accused of theft and thrown into the dungeon.

Frantic with fear, she looked everywhere for that plate, never finding it. Seeing that she was ripe with desperation, the samurai offered to rescue her from her fate in exchange for her hand in marriage. Despite her despair, she rejected him again. Enraged, he stabbed her with his sword, and threw her body into the castle well.

The well, named after Okiku, still exists. Whether Okiku herself really did is a whole other story. What is tangibly undeniable though, is the hard mesh wire bound tight over the mouth of the well, preventing anyone from falling in.

And preventing anyone from crawling out.

This may come as a surprise, but while 1998’s Sadako pays homage to 1825’s Oiwa, Oiwa herself was based on a real woman of the same name who lived in the 1600s. She was not murdered, not killed by a man, and lived happily into old age her with loving samurai husband. How she inspired centuries of ghost stories about vengeful women remains unclear, but I decided I wanted to meet her anyway.

Oiwa has two homes—both are in Tokyo. One is her grave, where her body lays, housed in Myoko-ji temple. The other is a shrine where she is said to reside—it is built into the garden of an old house in Yotsuya.

I decide to make a pilgrimage to the latter. I’ve read that film and theater directors who remake Yotsuya Kaidan come here to ask permission first. The house-shrine sits amidst residential property, flanked by vibrant red and white banners, concrete sculptures, and welcoming signage. I pay the necessary respects—entering from the left and washing my hands—and approach the heart of the shrine. I place a coin in the offering box, and pull the rope that sounds the heavy brass bell three times.

Oiwa is not the first woman to be killed in a story, then worshipped in real life. And certainly not the first ghost provided with a house to occupy. Spirit houses such as these exist in Japan, Korea, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia. They straddle various cultures and religions but are all created for the same purpose—to appease spirits that might otherwise cause trouble to the living.

I’m not sure what this says about the relationship between reverence and fear, demonization and deification. What it says about us as people, about how everything we destroy, we eventually worship. But as the deep thrum of the brass bell reverberates through the quiet neighborhood, I call into communion something larger than myself.

Maybe it is Oiwa. Maybe it is Sadako. Maybe it is every woman who has ever been beaten down, and emerged victorious. Maybe I am talking to all of these women. Maybe I am just talking to myself.

It’s been 25 years since Sadako and I first met, and our relationship has gone from strength to strength. I’ve rewatched the original Ringu, along with every sequel, prequel, spin-off, and remake. I’ve read the novel multiple times. I’ve dedicated poems, lectures, entire days to her. I believe I’ve also inherited a little bit of her attitude.

Alice never warmed up to her. Alice and I are no longer friends.

Sadako herself has gone through some changes. Since the demise of VHS, sequels find her emerging from laptop screens and airplane TVs—she refuses to be trapped in time. For a while, I worried that digital technology would submerge her into obsolescence, but she has proved time and again that she cannot be killed.

To survive, you must transform from victim to villain just like she did, and in doing so, must understand her pain.

I realize, of course, that I’ve yet to detail what happens after Sadako crawls out of that man’s television set. How she pours out of it like water from some leaking nightmare, limbs, dress, hair spread across living room floor. How the camera does close-ups on what it knows will repel you—the jagged movements of her broken body, the clumps of hair clinging to her face, the beds of her fingers where her nails used to be before she lost them clawing her way out of a well that became her tomb.

As the man trips over himself trying to escape, she straightens her body, rises above him, and with her famous glare, meets his gaze. Beneath her gaze, her eye the threshold to a grudge dark and unyielding, his heart stops. And when his body is found, his face is frozen in a perpetual scream—a message from beyond that cannot be wiped clean.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Sadako does not target her revenge specifically at those who’ve wronged her. It is not limited to the small seaside town from which she came. Her wrath is indiscriminate, accusatory. It speaks of our complicity as silent witnesses to her death.

But more important, there is one way to escape her wrath. Even if you chance upon that video. Even if you happen to watch it.

In the twist that ends Ringu, we learn the caveat to Sadako’s curse. If you want to live, you must make a copy of the tape, pass it on to someone else, and make sure they watch it. One life for another, and you will be spared.

This is the loophole that Sadako gives freely. To survive, you must transform from victim to villain just like she did, and in doing so, must understand her pain.

Into a well of your own you go: Who’s the monster now?

Excerpted from Dinner on Monster Island: Essays. Copyright © 2024, Tania de Rozario. Reproduced by permission of Harper Perennial. All rights reserved.