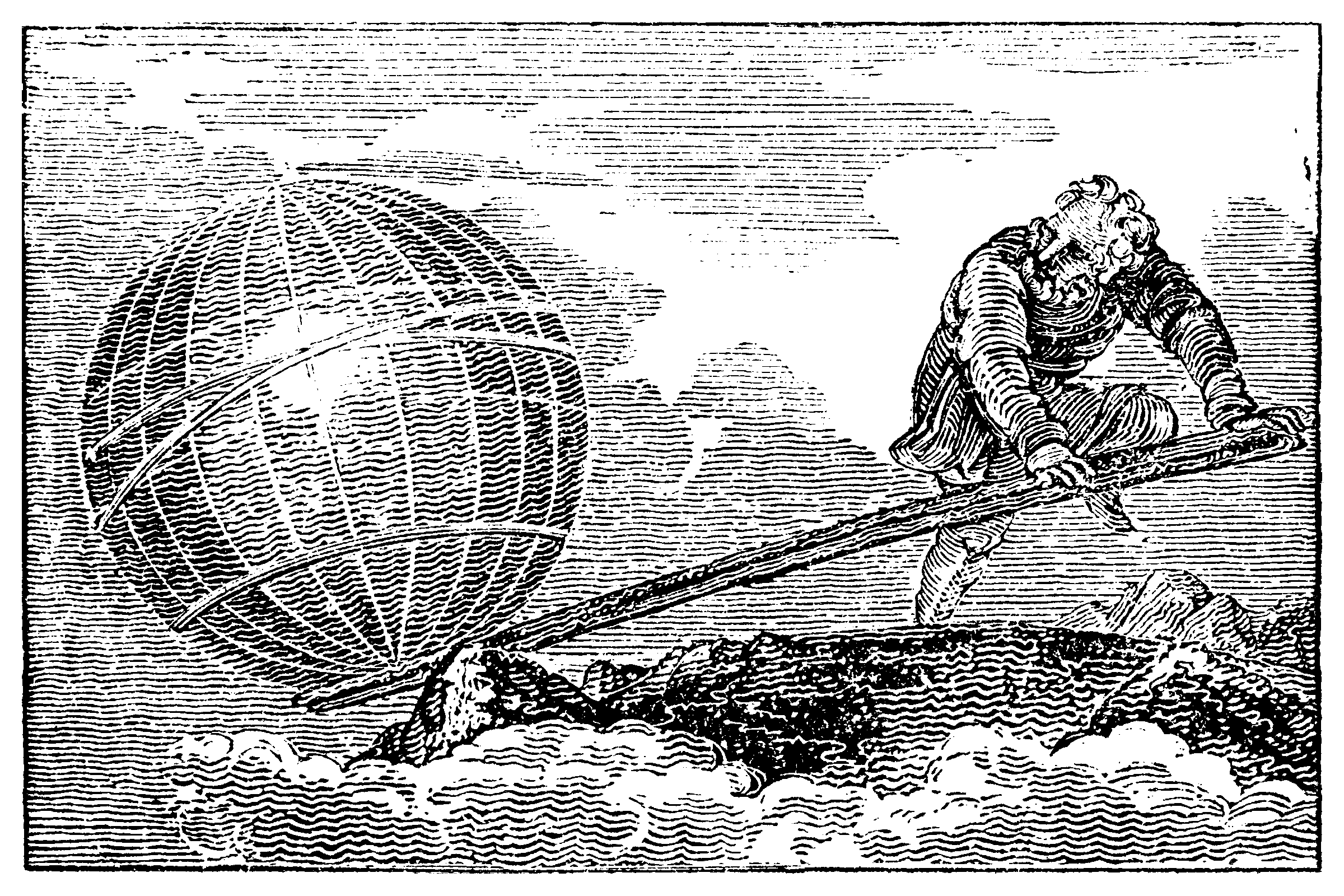

The ancient Greek Archimedes, the greatest scientist of his time, understood the principle of leverage better than any mortal ever had. With a long enough lever — a rigid bar resting over a fulcrum — Archimedes believed he could work mechanical miracles.

“Give me a place to stand,” the folklore of science has Archimedes proclaiming, “and I can move the world.”

Down through the centuries, political thinkers and leaders have embraced the majesty of that image. The great pamphleteer of 1776, Thomas Paine, saw the American Revolution as a lever that could move the political world.

“What Archimedes said of the mechanical powers,” Paine wrote in The Rights of Man, “may be applied to Reason and Liberty.”

In more modern times, President John F. Kennedy invoked Archimedes to make the case for a limited atomic bomb test ban treaty he signed with the Soviet Union. The treaty, JFK acknowledged in a 1963 United Nations address, wasn’t going to “put an end to war” or “secure freedom for all.” But the agreement, he went on, “could be a lever” that “can move the world to a just and lasting peace.”

We still, of course, haven’t reached that “just and lasting peace,” in no small part because the world has become a far more unequal place. Today we need a new lever — to move our world toward equity.

What could that lever be? A growing number of egalitarians feel they’ve found a handy one in the ratio of corporate CEO to worker pay.

This year, for the first time ever, publicly traded U.S. corporations must disclose the ratio between their CEO and typical worker compensation, a mandate that comes courtesy of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform act enacted in 2010. Thanks to this mandate, we now have an official benchmark we can use to see which U.S. corporations are making an effort to share the wealth and which aren’t.

We’ve so far learned from the new Dodd-Frank disclosures that 25 U.S. corporations last year paid their top executives over 1,000 times what they paid their median — most typical — workers.

Rewards like these are making a significant contribution to the growing divide between America’s extravagantly rich and everyone else. Some 60 percent of our nation’s top 0.1 percent owe their good fortune to their executive slots in America’s major corporations and banks.

These super rich also owe their good fortune to America’s taxpayers. Nearly every major American corporation is plumping up its profits with tax dollars from government contracts, tax breaks, and subsidies. These tax dollars are widening the gap between worker and CEO pay. But these same tax dollars, advocates for a more equal America believe, could help us significantly narrow corporate pay divides — and the inequality they engender.

Governments, for instance, could deny contracts for goods and services to corporations that pay their top executives outrageously more than their workers. They could condition subsidies and tax breaks on corporate pay practices as well. A company like Amazon wants a subsidy from taxpayers? No subsidies, taxpayers could insist, for corporations that reward the bulk of the benefits from those subsidies to their top executives.

Progressive legislators in about a half a dozen states have already introduced bills along these lines. One city — Portland, Oregon — has even put this leveraging principle into practice. Portland this year has begun taxing at a higher rate those corporations that are paying their top execs at over 100 and 250 times what their typical workers are earning.

CEO pay typically tracks corporate share prices. The more the share price of a CEO’s corporation rises, the more in compensation the CEO pockets. That dynamic gives CEOs a powerful incentive to jack up their company share price by any means necessary.

Today’s most popular CEO go-to strategy for jacking up share prices? That has become the share “buyback.” Top execs simply have their companies “buy back” their own corporate shares on the open market. These buybacks, notes business journalist Valentin Schmid, “artificially” boost earnings per share “by keeping earnings the same but reducing the number of shares.” That puts upward pressure on share prices.

CEOs can even have their companies borrow the money to buy back shares, then deduct the interest they pay on that debt off their corporate tax returns. Average taxpayers, in other words, end up subsidizing corporate stock buybacks that balloon the wealth of top corporate execs and other already rich corporate shareholders.

What sort of lever could end the stock buyback games executives play at average taxpayer expense?

U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders has just proposed one simple and straightforward answer. The Vermont lawmaker, working with Rep. Ro Khanna from California, has introduced legislation that would ban buybacks at any major U.S. corporation that either pays its workers less than $15 an hour or its execs over 150 times what the company’s typical workers are making.

The Sanders-Khanna legislation — the “Stop Welfare for Any Large Monopoly Amassing Revenue from Taxpayers Act” — puts a special focus on retail giant Walmart, a corporation that last year pocketed over $13 billion in profits and then began buying back $20 billion of its own stock.

In 2017, Walmart’s CEO took home 1,188 times the pay of Walmart’s most typical employee.

A half century ago, in a much more equal United States, precious few top corporate execs ever pocketed over 30 times what their workers were making. CEOs at major U.S. firms last year averaged 361 times the pay of average American workers.

If Archimedes could move the world, we can move that ratio.