ROBERT CAPA'S FALLING SOLDIER

BEFORE THE LENS

Richard Whelan

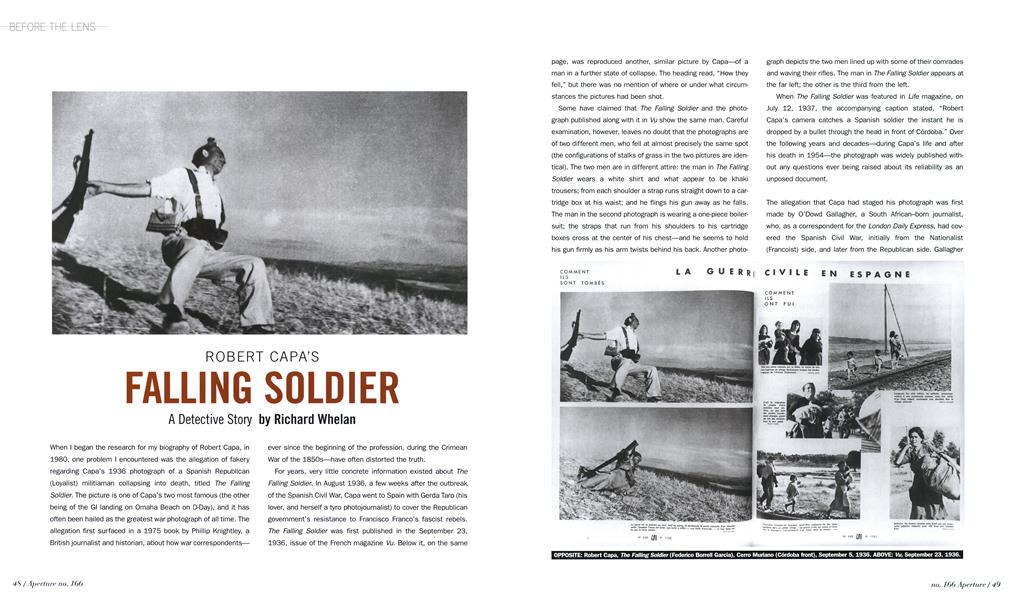

When I began the research for my biography of Robert Capa, in 1980, one problem I encountered was the allegation of fakery regarding Capa's 1936 photograph of a Spanish Republican (Loyalist) militiaman collapsing into death, titled The Falling Soldier. The picture is one of Capa's two most famous (the other being of the GI landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day), and it has often been hailed as the greatest war photograph of all time. The allegation first surfaced in a 1975 book by Phillip Knightley, a British journalist and historian, about how war correspondentsever since the beginning of the profession, during the Crimean War of the 1850s-have often distorted the truth.

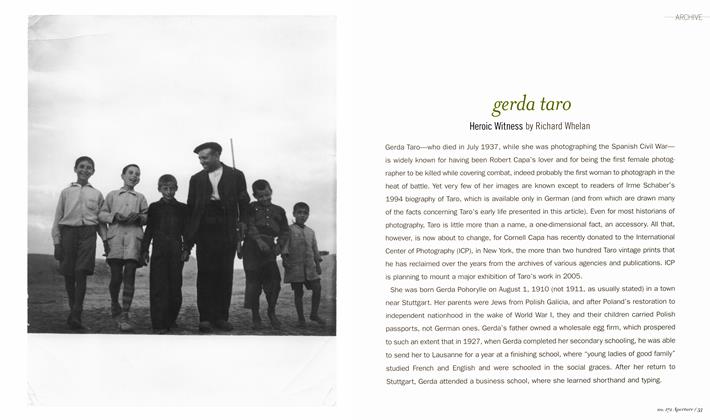

For years, very little concrete information existed about The Falling Soldier. In August 1936, a few weeks after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Capa went to Spain with Gerda Taro (his lover, and herself a tyro photojournalist) to cover the Republican government's resistance to Francisco Franco's fascist rebels. The Falling Soldier was first published in the September 23, 1936, issue of the French magazine Vu. Below it, on the same page, was reproduced another, similar picture by Capa—of a man in a further state of collapse. The heading read, “How they fell,” but there was no mention of where or under what circumstances the pictures had been shot.

Some have claimed that The Falling Soldier and the photograph published along with it in Vu show the same man. Careful examination, however, leaves no doubt that the photographs are of two different men, who fell at almost precisely the same spot (the configurations of stalks of grass in the two pictures are identical). The two men are in different attire: the man in The Falling Soldier wears a white shirt and what appear to be khaki trousers; from each shoulder a strap runs straight down to a cartridge box at his waist; and he flings his gun away as he falls. The man in the second photograph is wearing a one-piece boilersuit; the straps that run from his shoulders to his cartridge boxes cross at the center of his chest—and he seems to hold his gun firmly as his arm twists behind his back. Another photograph depicts the two men lined up with some of their comrades and waving their rifles. The man in The Falling Soldier appears at the far left; the other is the third from the left.

When The Falling Soldier was featured in Life magazine, on July 12, 1937, the accompanying caption stated, “Robert Capa’s camera catches a Spanish soldier the instant he is dropped by a bullet through the head in front of Córdoba.” Over the following years and decades—during Capa’s life and after his death in 1954—the photograph was widely published without any questions ever being raised about its reliability as an unposed document.

The allegation that Capa had staged his photograph was first made by O’Dowd Gallagher, a South African-born journalist, who, as a correspondent for the London Daily Express, had covered the Spanish Civil War, initially from the Nationalist (Francoist) side, and later from the Republican side. Gallagher told Phillip Knightley—who published the story in his 1975 book The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam; The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker—that “at one stage of the war he and Capa were sharing a hotel room” (the emphasis is added here to make the point that Gallagher seems not to have remembered where or when during the war he had shared a room with Capa). Gallagher told Knightley that at that time “there had been little action for several days, and Capa and others complained to the Republican officers that he could not get any pictures. Finally ... a Republican officer told them he would detail some troops to go with Capa to some trenches nearby, and they would stage some manoeuvres for them to photograph.” Although Knightley made a great show of leaving no stone unturned in his research into the subject, it is odd that he did not realize, or did not think to point out, that when Capa’s photograph was first published, late in September 1936, Gallagher was covering the war from the Nationalist side—and yet Gallagher said that Republican officers had staged the maneuvers for the photographers

"As they charged, the photographer timidly raised his camera to the top of the parapet and, without looking, but at the instant of the first machine gun burst, pressed the button."

In 1978 Jorge Lewinski published in his book The Camera at War his own interview with Gallagher, in which the journalist now claimed that Franco’s troops, not Republican ones, had staged the maneuvers. Gallagher told Lewinski that he and a group of other journalists were near San Sebastián, about five miles from IrCin. He stated:

Most of us reporters and photographers were there in a small shabby hotel. We went into Franco’s Spain across the Irún River, when allowed by Franco’s press officers in Burgos. . . . Once only the photographers were invited. . . . Capa told me of this occasion. They were given simulated battle scenes. Franco ’s troops were dressed in “uniforms ” and armed and they simulated attacks and defence. Smoke bombs were used to give atmosphere.

Capa, however, would never have had anything to do with Franco’s troops; he was a passionate antifascist and covered the Spanish Civil War as a committed partisan for the Republican side. And, as a photographer who was by the summer of 1936 well known for his affiliation with several French leftist publications, he would never have been welcome in Franco-held territory—except to be arrested. Furthermore, Capa’s travels in Spain between the outbreak of the civil war and the first publication of his photograph can be traced; he was never anywhere within several hundred miles of San Sebastián. Gallagher probably did share a room near San Sebastián with a photographer who may have made pictures of posed exercises, but that photographer was not Capa.

The obvious inconsistencies in Gallagher’s accounts to Knightley and Lewinski should have discredited his testimony, thereby ending the controversy immediately. Nearly forty years after the events, Gallagher’s memory had clearly played a trick on him. No doubt in perfectly good faith he confused Capa with someone else with whom he had shared a hotel room in 1936. There is, in fact, no evidence that Gallagher and Capa ever met before January 1939: on the night of January 24-25, Capa photographed Gallagher and Herbert Matthews typing their last dispatches before the three of them left the beleaguered city together to drive north to the French border and safety.

That a lapse of memory like Gallagher’s is possible—even unsurprising—was dramatically demonstrated to me while I was conducting interviews for my Capa biography. When I spoke with cartoonist Bill Mauldin, whose vigor inspired my confidence in his perfect recall, he told me that he had been with Capa on the Roer River front in the spring of 1945. I told him that I was surprised to hear that, as I was quite certain that Capa had been somewhere else at that time. Mauldin assailed my doubts by assuring me that he remembered so clearly being with the photographer that he could even describe the images Capa made on the Roer front, which were published in Life. His descriptions were so precise that I recognized the photographs instantly when I looked them up in the magazine. They had, however, been made by George Silk, not by Capa, who was then covering the paratroopers who jumped east of the Rhine.

In a July 5, 1998, article in the London newspaper Night & Day, Knightley stated that he had asked Cornell Capa or Magnum to “release the roll of film on which the two ‘moments of death’ appear so that we could see the whole sequence of shots.” He then complained that his requests had not been met, and by that complaint he clearly meant to insinuate that the negatives must support his allegation. In fact, the roll of film in question was cut into snippets by Capa’s darkroom man, Csiki Weiss, soon after Weiss had developed the roll. That was normal practice in Capa’s darkroom, as some publications insisted on making halftone plates from original negatives; filmstrips were cut to provide the requested frame, while keeping the rest of the negatives available for other publications. It is important to remember that Capa’s photographs were thought of simply as journalistic pictures with a brief period of timely interest, after which they would be considered stale news.

The negatives of the two “moment of death” photographs were evidently given out for publication and never returned; they have not been seen since the 1930s. All modern prints of The Falling Soldier have been made from a copy negative of the vintage print in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, in New York.

Capa’s own best-known account of the circumstances of his photograph is that reported by John Hersey in a 1947 profile titled “The Man Who Invented Himself.” Capa and Hersey were longtime friends and, at some unspecified time, Capa told Hersey an obviously tongue-in-cheek and characteristically picaresque and self-deprecating story about making The Falling Soldier. He said that in August 1936 he had been in the Catalonian and Andalusian mountains, where he had witnessed a tragic scene of Republican volunteer fighters—fanatical but ignorant—repeatedly charging a nest of fascist machine gunners. As Hersey retold Capa’s account: “They repeated this gallant and ingenuous procedure several times, until finally, as they charged, the photographer timidly raised his camera to the top of the parapet and, without looking, but at the instant of the first machine gun burst, pressed the button.” After that, Hersey wrote, Capa sent the film to Paris, undeveloped. Two months later he was notified that the random snapshot had turned out to be a clear picture of a brave man in the act of falling dead as he ran, and it had been published, over the name of Capa, in newspapers all over the world.

In a world eager to kill sacred cows, the Gallagher/ Knightley/Lewinski allegation spread like wildfire. For a time, it seemed that any mention of Capa's name would elicit, even from people with little knowledge of the history of photography, a remark along the lines of "Wasn't he the guy that faked that famous picture?"

Soon after Knightley’s book was published, in 1975, Cornell Capa asked several of the people who had been among his brother’s closest friends during the Spanish Civil War to refute Gallagher’s allegation. Csiki Weiss, living in Mexico City and married to Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, sent Cornell a telegram stating that, as Robert Capa’s darkroom man at the time, he could positively affirm that the negative of The Falling Soldier was “absolutely genuine.” Capa’s friend, journalist Martha Gellhorn spoke out vehemently in Capa’s defense, stating that for a man of such great integrity to have faked a photograph was unthinkable. When she and Knightley appeared together on British television to discuss The Falling Soldier, she became so furious that she stormed off the set in the middle of the program.

In a world eager to kill sacred cows, the Gallagher/ Knightley/Lewinski allegation spread like wildfire. For a time, it seemed that any mention of Capa’s name would elicit, even from people with little knowledge of the history of photography, a remark along the lines of “Wasn’t he the guy that faked that famous picture?” Rumors also flew about the man in the photograph. In 1985, for instance, at the photographic festival held annually in Arles, someone circulated an open letter claiming that the man in The Falling Soldier was still very much alive, residing in Venezuela.

In my biography of Capa, which was published in 1985, I began the discussion of The Falling Soldier by stating my case for establishing the place and date of the photograph. In his 1937 book The Spanish Cockpit, Swiss journalist Franz Borkenau recounts that he witnessed a battle around the village of Cerro Muriano, eight miles north of Córdoba, on the afternoon of September 5, 1936. He was accompanied by two photographers from the magazine Vu: Hans Namuth and Georg Reisner.

Brotóns knew that the man in the photograph must have belonged to the militia regiment from Alcoy.... He then confirmed in the Spanish government archives in Salamanca and Madrid that only one member of the Columna Alcoyana had been killed at Cerro Muriano on [September 5, 1936] —Federico Borrell Garcia.

That afternoon Namuth and Reisner photographed the terrorstricken inhabitants of the village as they were fleeing a fascist air raid. I interviewed Namuth, who told me that he had not seen Capa and Taro in Cerro Muriano. But when Vu, in its issue of September 23,1936, published Capa’s photographs of some of the same people that Namuth and Reisner had photographed along the same road outside Cerro Muriano, Namuth realized that Capa had indeed been there that day.

That fact provided the essential clue for pinpointing where Capa made The Falling Soldier. On the vintage prints, preserved in the files of Capa’s estate with their original chronological numbering written on the back, the numbers of the sequence to which The Falling Soldier belongs immediately precede those of the Cerro Muriano refugee series. I thus deduced (and stated in my biography of Capa) that he made The Falling Soldier at or near Cerro Muriano, on or just before September 5, 1936.

The controversy raged on—with an overabundance of hot tempers and a sad dearth of objective analysis or research—until a fantastic breakthrough occurred, in August 1996, when I received a telephone call from Rita Grosvenor, a British journalist based in Spain. To my amazement, Ms. Grosvenor told me that she had written an article about a Spaniard named Mario Brotóns Jordá, who had identified the man in The Falling Soldier as one Federico Borrell Garcia, who had been killed in battle at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936. Grosvenor’s article was to be published in the London Observer on Sunday, September 1, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of Capa’s photograph and of Borrell’s death.

The story of how Brotóns made his discovery is a fascinating one. Born in the village of Alcoy, near Alicante, in southeastern Spain, Brotóns had himself joined the local Loyalist militia, the so-called Columna Alcoyana, at the age of fourteen—and was a combatant in the battle against the Francoist forces that took place on and around the hill known as La Loma de Las Malagueñas at Cerro Muriano on that September day in 1936. When Brotóns’s friend Ricard Bañó, a young Alcoy historian, mentioned to him that he had read (in my Capa biography, incidentally) that Capa’s photograph might have been made during the battle at Cerro Muriano, Brotóns began his own research. He knew that the man in the photograph must have belonged to the militia regiment from Alcoy, as he wore distinctive cartridge cases specially designed by the commander of the Columna Alcoyana and made by the leather craftsmen in Alcoy; no one in any of the other units participating in the battle at Cerro Muriano would have worn such cartridge cases. Brotóns then confirmed in the Spanish government archives in Salamanca and Madrid that only one member of the Columna Alcoyana had been killed at Cerro Muriano on that particular day—Federico Borrell García. The other Loyalists killed there that day belonged to other units. Brotóns then showed Capa’s photograph to Federico’s younger brother, Everisto, who confirmed the identification.

Brotóns revealed his discovery in the second edition of his 1995 self-published book, Retazos de una época de inquietudes. There, he recounts that Borrell (whose nickname was “Taino”) was a twenty-four-year-old mill worker from Alcoy. He had been a founding member of the local branch of the Juventudes Libertarias (Libertarian Youth), an organization affiliated with the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, or CNT (an important piece of evidence, as the man in the photograph is wearing a CNT cap). Borrell was one of about fifty militiamen who had arrived at Cerro Muriano on the morning of September 5 to reinforce the Columna Alcoyana’s front line. That afternoon he was defending the artillery battery in the rearguard of the Alcoy Infantry when enemy troops Infiltrated behind the Loyalist lines and began firing at them from behind as well as from in front, hoping to squeeze the Loyalists in a vise. It was about five o’clock when Borrell was fatally shot. That time accords with the long shadows in Capa’s photograph.

Brotóns died soon after the publication of his book. When Rita Grosvenor came across a copy of it in Alicante, where she was living, she recognized both the importance and the timeliness of his revelation. She went to Alcoy with a reproduction of the famous photograph and showed it to Maria, the widow of Federico’s brother Everisto. Maria told Grosvenor that the man was certainly Federico. “I knew him well,” she said. She showed Grosvenor some family photographs that further confirmed the identification.

At the end of her article Grosvenor reported that Knightley “remains sceptical but promises: ‘If I’m wrong, I’ll apologise to Cornell Capa.’” In July 1998, at the time of a Robert Capa retrospective exhibition in London, Knightley came out with an article dismissing Brotóns’s discovery and stating, “The famous photograph is almost certainly a fake, Capa posed it.” He went on to argue fatuously, “Federico could have posed for the photograph before he was killed.”

To provide a definitive refutation of this absurd suggestion, I turned to an expert—a man who is uniquely qualified in this particular case: Captain Robert L. Franks, chief homicide detective of the Memphis Police Department, and a talented sculptor and photographer in his own right. I asked Franks, in September 2000, if he might give a reading of the photograph as if it were evidence in a murder case. In his analysis, he said that the first thing that struck him as odd about The Falling Soldier was that the man “had been standing flat footed when he was shot. He clearly was not in stride when he was shot.” He went on to say in his written report:

As an investigator you have to put yourself in the place of the victim and the suspect to draw a workable solution. . . . The image is slightly out of focus and the camera lens is set on a large aperture as if Mr. Capa was about to take a portrait of this soldier from the ground looking up at him. Fiad the danger passed? Did the soldier get up on his own or did Mr. Capa ask him to stand up so a picture could be taken? We will never know. Think about standing flat-footed and holding a rifle in your hand down by your waist instead of port arm in ready combat position. There are many questions that are unresolved. Was this picture posed? I think not, based on the human reflex response. You will notice that the soldier’s left hand, which is partially showing under his left leg, is in a semi-closed position. If the fall was, in fact, staged, the hand would be open to catch his fall (simply a self-preservation reflex to keep from getting hurt). The right hand that held the rifle is open, which would indicate to me a relaxed state of the muscle. No soldier would let his rifle fall into the dirt for fear of malfunction of the weapon at a later time.

The most telling element, in Franks’s reading, is the soldier’s left hand, seen below his horizontal left thigh. Franks wrote (and elaborated to me in conversation) that the fact that the fingers are somewhat curled toward the palm clearly indicates that the man’s muscles have gone limp and that he is already dead. Hardly anyone faking death would ever know that such a hand position was necessary in order to make the photograph realistic. It would be nearly impossible for any conscious person to resist the reflex impulse to brace his fall by flexing his hand strongly backward at the wrist and extending his fingers out straight.

"...The camera lens is set on a large aperture as if Mr. Capa was about to take a portrait of this soldier from the ground looking up at him. ... Did the soldier get up on his own or did Mr. Capa ask him to stand up so a picture could be taken? We will never know...."

Captain Franks’s inferences that the man in The Falling Soldier had been standing flat-footed and not expecting to use his rifle led me to reconsider a story that Flansel Mieth, a Life staff photographer in the late 1930s, wrote to me in a letter of March 19, 1982. Capa had once told her about the situation in which he had made his famous photograph. She said that Capa, who was very upset, told her that when he’d made the famous photograph, “They were fooling around. We all were fooling around. We felt good. There was no shooting.” Then suddenly, without warning, they were fired upon. Capa implied that he felt at least partially responsible for the death of the man in The Falling Soldier.

Taking all of the foregoing information into consideration, I have come to a hypothesis about Robert Capa’s experience on La Loma de Las Malagueñas on the afternoon of September 5, 1936, during the battle between various Loyalist militias and the Francoist forces.

Capa encountered a group of militiamen (and at least one militiawoman) from several units—Francisco Borrell García among them—in what was at that moment a quiet sector. Having decided to play around a bit for the benefit of Capa’s camera, the men began by standing in a line and brandishing their rifles. Then, with Capa running beside them, they jumped across a shallow gully and hugged the ground at the top of its far side, pretending to take aim and fire their rifles. I have always stated that the militiapersons then got up and continued their advance, running down the hillside. I now realize that what must have happened instead is that at least a couple of the men, including Borrell, turned around and climbed back up the uphill side of the gully.

In Capa’s two photographs of the soldiers crossing the gully, we can clearly see, in the upper-left corner of each picture, upstanding stalks of grass like those underfoot in both of the “moment of death” photographs.

Once Borrell had climbed out of the gully, he evidently stood up, back no more than a pace or two from the edge and facing down the hillside, so that Capa (who had remained in the gully) could photograph him. Just as Capa was about to press his shutter release, a hidden enemy machine gun opened fire. Borrell, hit probably in the head or heart, died instantly and went limp while still on his feet, as Capa’s photograph shows. (What some viewers have assumed to be a piece of the man’s skull blown off is actually the tassel on his cap.) Immediately after he had fallen to the ground, comrades must have dragged his body back into the gully. That would explain why his corpse is not visible in the other picture.

Indeed, Franks concluded that the man in The Falling Soldier was the first to be shot. He wrote, “I base this upon the cloud formation that seems to be tighter in [The Falling Soldier] and more dissipated in the [other] picture. The second soldier’s photograph is in focus, which indicates to me that Robert Capa had time to attend to the settings on his camera between the two shots.”

As for the other soldier, Franks wrote that the photograph of him “indicates to me that the soldier was on his knees, leaning back with his buttocks resting on the heels of his feet, the rifle being held in his right hand and the rifle muzzle pointing up and slightly to the rear. As the soldier was thrown back by a bullet, gravity took over pulling the weight of the barrel towards the ground.”

Capa—presumably with at least a few of the militiapersons— must have remained safely in the gully until the coast was sufficiently clear to allow a return to the village.

I firmly believe that there can be no further doubt that The Falling Soldier is a photograph of Federico Borrell Garcia at the moment of his death during the battle at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936. May the slanderous controversy that has plagued Robert Capa’s reputation for more than twenty-five years now, at last, come to an end with a verdict decisively in favor of Capa’s integrity. It is time to let both Capa and Borrell rest in peace, and to acclaim The Falling Soldier once again as an unquestioned masterpiece of photojournalism and as perhaps the greatest war photograph ever made. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Word About Angels

Spring 2002 By Carole Naggar -

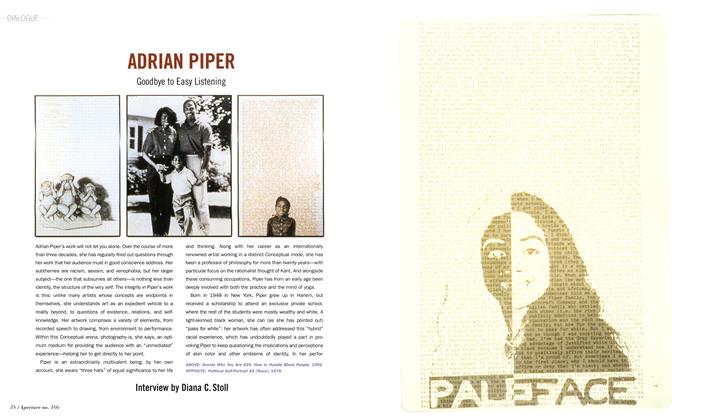

Dialogue

DialogueAdrian Piper

Spring 2002 By Diana C. Stoll -

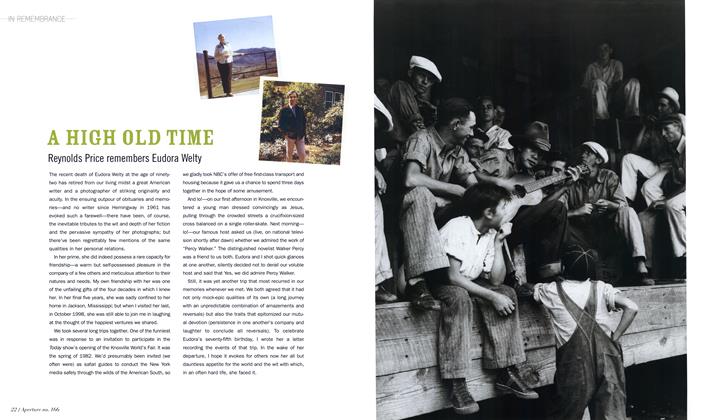

In Remembrance

In RemembranceA High Old Time

Spring 2002 -

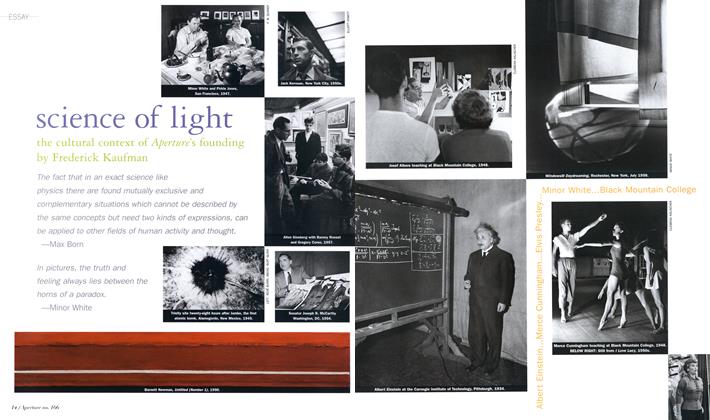

Essay

EssayScience Of Light

Spring 2002 By Frederick Kaufman -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaNew Style Sacred Allegory The Video Art Of Shirin Neshat

Spring 2002 By Minna Proctor -

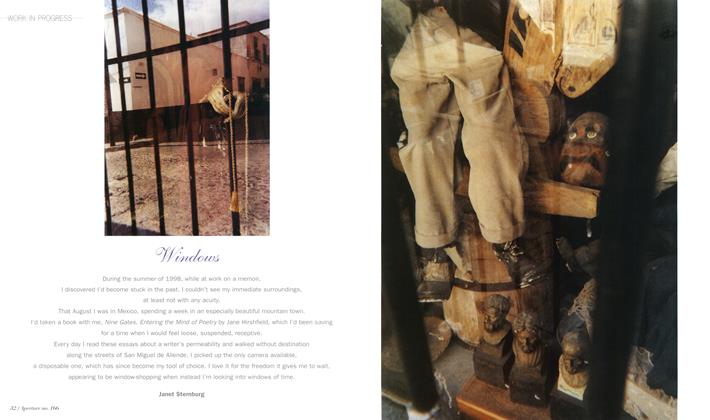

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressWindows

Spring 2002 By Janet Sternburg

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Richard Whelan

Before The Lens

-

Before The Lens

Before The LensRichard Avedon And Lee Friedlander: One Day In May

Fall 2007 By Jeffrey Fraenkel -

Before The Lens

Before The LensJessie At 18 Daughter, Model, Muse Jessie Mann On Being Photographed

Winter 2001 By Jessie Mann -

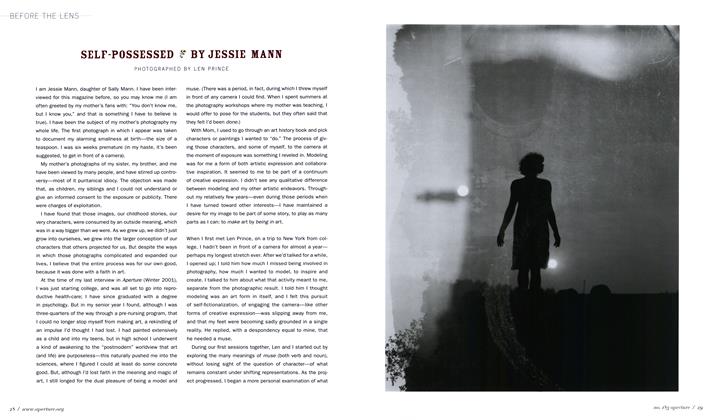

Before The Lens

Before The LensSelf-Possessed

Summer 2006 By Jessie Mann -

Before The Lens

Before The LensJh Engström: Looking For Presence

Spring 2008 By Martin Jaeggi -

Before The Lens

Before The LensTiny-Erin Photographs By Mary Ellen Mark

Winter 2005 By Mary Ellen Mark, Martin Bell -

Before The Lens

Before The LensLatent Image

Summer 2000 By Michael L. Sand, Yoshio Uemura