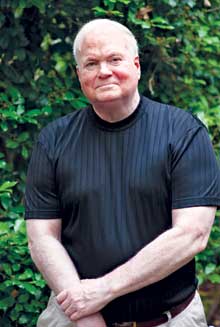

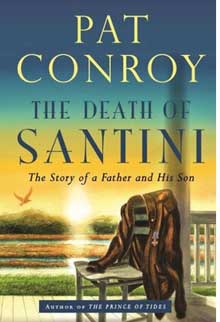

As his new memoir The Death of Santini floods bookstores nationwide, we bring you a free-style, freewheeling, unabridged conversation with the man whose life has been an open book.

As his new memoir The Death of Santini floods bookstores nationwide, we bring you a free-style, freewheeling, unabridged conversation with the man whose life has been an open book.

By Margaret Evans, Editor

If you’ve lived in Beaufort for any time at all, you probably have a Pat Conroy story. Maybe you played basketball together as teenagers, or he was your high school English teacher. Perhaps you were in his writers’ group, or he was your neighbor on Fripp, or you still smoke cigars together on his back porch every Sunday afternoon. Maybe your association is more ephemeral – you ran into him once at Publix, or at the old Bay Street Trading Co., or in his favorite restaurant, Griffin Market. But you really connected. Or maybe you’ve just read his books, and you feel like you’ve known him forever. No matter how fast or loose the relationship, we Beaufortonians all think of Pat Conroy as ours. He belongs to us. He’s part of our mythology. Heck, he wrote our mythology.

My own Pat Conroy story goes back over 20 years. I was a young newlywed living on Fripp Island, with a shiny new masters in English and nowhere to use it. Enter the famous writer – he happened to be my neighbor – who generously offered me a job as his research assistant. To this day, I’m not sure whether he actually needed me or was just being nice. (That would be just like him.) It was a part-time gig; I spent most of my days working in a little dress shop while Pat spent his writing a book called Beach Music. He was a wonderful boss and we became friends, but when the novel was finished, so was  my job. Our lives meandered off in different directions. Looking back, though, I see we were always on strangely similar paths. In the two decades since, we both divorced and remarried, and we both left Fripp and moved into town. Career-wise, mine has clearly been the more stunning trajectory. No longer a shop girl, I am now the proud editor of this illustrious publication. Pat, on the other hand, has been content to remain as he was when I first met him – a world-famous, critically celebrated, bestselling author and American icon. What can I say? Some folks just aren’t that ambitious.

my job. Our lives meandered off in different directions. Looking back, though, I see we were always on strangely similar paths. In the two decades since, we both divorced and remarried, and we both left Fripp and moved into town. Career-wise, mine has clearly been the more stunning trajectory. No longer a shop girl, I am now the proud editor of this illustrious publication. Pat, on the other hand, has been content to remain as he was when I first met him – a world-famous, critically celebrated, bestselling author and American icon. What can I say? Some folks just aren’t that ambitious.

Pat Conroy talks a lot about circles – he believes in their power – and today as I sit on his cozy back porch, looking out over Battery Creek and the autumn-gilded marsh, it occurs to me that those of us who fall into his orbit, whenever and however that happens, tend to stay there. Like planets circling the sun, we just keep coming back around. Lately, I’ve been working for Pat again. Again, it’s a part-time gig. And again, I’m not sure he really needs me. But I’m not asking any questions . . .

Not about that, anyway. I am here to ask questions about The Death of Santini, Pat’s new memoir released just last week. In this book, we finally meet the family that launched a thousand novels, face to face, without their fictional masks, including the rage-driven father Pat says he remembers hating “even when I was in diapers.” It is a beautiful, harrowing book that, for me – as someone who loves Pat Conroy – was as difficult to read as it was to put down.

We’ve been talking on this porch for almost two hours, and much to my journalistic delight, Pat keeps telling me that “nothing’s off the record” . . .

Margaret Evans: Pat, you’ve said that you don’t take pleasure in writing your books. Unlike your wife Cassandra King, who has fun with her writing (“I crack myself up,” she recently told the Post & Courier), you find the process grueling and painful. I’m guessing that writing The Death of Santini was a bit like extracting your own teeth?

Cassandra King, who has fun with her writing (“I crack myself up,” she recently told the Post & Courier), you find the process grueling and painful. I’m guessing that writing The Death of Santini was a bit like extracting your own teeth?

Pat Conroy: It was awful. Just awful. And it’s been funny to hear the array of reactions from my brothers and sisters. My brother Jim was the most terrified about the book. He was dreading it. So, he reads it, and I call him up, “What’s the verdict, Jim?” The Dark One (that’s what I call him) is not effusive; he’s very male, judgmental, restrained. Jim said I’d written an “adequate” book. So I call Mike – six weeks after sending him the book – and he says, “Nah, Pat . . . I’ve been so busy. Haven’t even opened it yet.” My sister Kathy seems to like it, which pleases and surprises me.

ME: Kathy doesn’t normally like your books?

PC: Actually, I don’t know. Basically, my family never mentions to me that they’ve even read the books. Including my daughters. Anyway, my brother Tim, like me, is an emotional male. Tim is all out there. He lets you know how he feels. He said, “Pat, reading your book was like taking a lead pipe and hitting myself in the head over and over for 350 pages. I found it agonizing. Why did we have to go through all that? We were just little kids. We were children. What were these people thinking?” He was reading it out loud to his wife Terrye, but finally had to stop because she kept breaking down, weeping, over everything we’d been through. Tim says, “I’ll be able to tell you in about 15 or 20 years what I think of it, but right now I’m so upset by it, so distraught and angry over it, than I can barely talk to you.” I said, “That seems like a good read.”

ME: What about your sister Carol? Has she seen the book?

PC: She will never see the book unless she buys it or gets it from the library. We don’t talk. By the way, my siblings all agreed that I was way too easy on Carol in the book . . .

ME: Carol comes across in some parts of the book as certifiably insane. In other parts, she’s like this prophetic voice. You write of your sister, “With odd skills of articulation, she spoke truths her parents were not interested in hearing.” So what do you think it was, Pat? Nurture or nature? Was Carol genetically predisposed to mental illness, or was she just a sensitive, poetic girl driven crazy by growing up in that house?

PC: I don’t know. Let’s just put it this way – there was no way Carol could have grown up in that house without going crazy.

ME: I used to think you were exaggerating when you’d write about your father. But you say in this book that Don Conroy was actually meaner than Bull Meechum, the character you based on him in The Great Santini. You say your editor made you add some “nice” scenes to that book because she didn’t think the readers would buy the character of Bull as you’d written him. I found that shocking!

ME: I used to think you were exaggerating when you’d write about your father. But you say in this book that Don Conroy was actually meaner than Bull Meechum, the character you based on him in The Great Santini. You say your editor made you add some “nice” scenes to that book because she didn’t think the readers would buy the character of Bull as you’d written him. I found that shocking!

PC: It’s true. The scene when he gives his son the flight jacket? Or when he gives his daughter roses? Never happened. None of it. When my family was sitting together at the premier of the “Santini” movie, and Duvall was slapping the mother (played by Blythe Danner) around and raging at the kids, my brother Jim leans over and whispers, “Bambi. Duvall’s like Bambi up there compared to Dad.”

ME: Looking back, and given your family’s history, do you think it’s possible that your father was mentally ill?

PC: No, I think he was just an asshole. He was just a jerk from the word Go. He came out of a  civilization of poor, mean, hard Irishmen from Chicago. It was a tough society he came from, and he was a product of that society.

civilization of poor, mean, hard Irishmen from Chicago. It was a tough society he came from, and he was a product of that society.

ME: While reading this book, it occurred to me that in all your books – and throughout your life – you have always identified with those who suffer. The underdogs. “The wretched of the earth.” Whether it be blacks in the Jim Crow South, or gays during the AIDS crisis in San Francisco, or your own grandmother chained to a life of poverty in rural Alabama . . . Where there is suffering, that’s where you are. That’s where you’re most alive. I think it’s where your art comes from. I know you always credit your mom for turning you into a writer, by instilling in you a love of language at a young age. But is it possible that in some strange way, your father had a hand in your writerly destiny, too? By giving you this unintentional gift of great empathy?

PC: That’s very possible. The writer Katherine Clark is currently doing an oral biography of me, and our interviews have been grueling . . . it’s been like going through therapy all over again. In fact, she’s actually interviewing my old therapist, Dr. Marion O’Neill, whom I credit with saving my life. When Marion first took me on, I was in terrible shape. I was driving from Fripp to Hilton Head five days a week, for three hours of therapy a day. And Marion only took me as a patient on one condition. She made me promise not to commit suicide while seeing her. She said, “If the author of The Prince of Tides kills himself under my care, it will end my career. I’ll be finished.” (Laughs)

ME: So she put that on you?

PC: She put that on me. The very first day. And it worked. She made me laugh. Anyway, Dr. Marion O’Neill told my biographer recently, “Pat has to see himself as a hero. It’s because his father was a warrior.” This was a whole new insight for me! It answered so many questions. Like… Why have I gotten in so many fights throughout my life? Daufuskie . . . The Citadel . . . SCAD . . . various school boards. There’ve been a million of them. I’ve always wondered why I keep getting myself into these fights. Hearing these words from Marion, it suddenly hit me: I’m the son of a warrior. It’s in me. It’s in my gene pool. I’ve got my dad’s genes, and, God, it has screwed up my life!

PC: She put that on me. The very first day. And it worked. She made me laugh. Anyway, Dr. Marion O’Neill told my biographer recently, “Pat has to see himself as a hero. It’s because his father was a warrior.” This was a whole new insight for me! It answered so many questions. Like… Why have I gotten in so many fights throughout my life? Daufuskie . . . The Citadel . . . SCAD . . . various school boards. There’ve been a million of them. I’ve always wondered why I keep getting myself into these fights. Hearing these words from Marion, it suddenly hit me: I’m the son of a warrior. It’s in me. It’s in my gene pool. I’ve got my dad’s genes, and, God, it has screwed up my life!

ME: Yes, but you learned to channel that warrior’s impulse, that anger, toward . . .

PC: Toward suicide. I channeled my anger toward suicide. (Laughs)

ME: Well, I was going to say “toward good causes and into your writing.” But, okay. Let’s talk about the suicide thing. Do you still struggle with that self-destructive impulse?

PC: Well, I’m getting older now, so I no longer feel like I need to hurry the process along. It’ll happen in a couple of years, anyway. (Laughs) Honestly, though . . . No, I don’t struggle with it now like I did.

ME: Do you think that might be, in part, because of your wife Sandra?

PC: Yeah, I do. Absolutely.

ME: She’s brought a real gentle influence into your life.

PC: She’s been fabulous. She’s a great woman. Beautiful. Sweet. And she’s a damn good writer.

ME: I know. I’m not sure what she sees in you . . .

PC: (Laughs.) No kidding. You know, I remember sitting in my adolescent psychology class at The Citadel with Oliver Bowman – great teacher – who stunned me when he said that if you grew up in a house where the mother was beaten up, or the children were beaten up, there is something like a 60% chance that you will beat your wife and children. I remember thinking, “Oh great . . . there’s some poor girl out there, I haven’t even met her yet, and I’m gonna be beating the living daylights out of her, and she hasn’t done a f***ing thing . . . and then, we’ll have kids, and I’ll be beating them, too. Because of a stat??” It was horrifying to me.

ME: Do you think you made a decision, then and there, not to let that happen?

PC: I always felt that if I ever did that, I’d kill myself.

ME: So, going back to the nature/nurture question . . . Is it possible that you don’t just learn to be an abuser, but that it’s somehow in your DNA? Like, you can get the “anger gene”?

PC: Oh, yeah . . . I think I did. When I was talking to my biographer about Dad I said, “My entire life has been about controlling the anger I either inherited or ‘picked up’ from my father.” I think it’s both. And I think it’s a huge part of my life, and of my writing life. I think there’s a huge amount of anger contained in my writing.

ME: I think so, too. But sometimes it’s tamped down by humor.

PC: That’s the Conroy way. You know, I’m still horrified that we laughed at that joke the Dark One made after Tom’s funeral.

ME: And I’m so horrified, I’m leaving that joke out of this interview entirely. My readers will just have to buy the book. But to bring them up to speed, your youngest brother Tom committed suicide by jumping off a building in Columbia. He was schizophrenic, right?

PC: Paranoid schizophrenia was his diagnosis. It started in his teenage years. As the mother of a twelve-year-old, doesn’t that scare you to death?

ME: So much so that I will now abruptly change the subject. According to the book, your dad went through a rather radical transformation in his later years. He became a kinder, gentler Don Conroy. What brought this about? Was it the death of your brother? The birth of grandchildren? The loss of his wife? It’s never quite clear in the book.

ME: So much so that I will now abruptly change the subject. According to the book, your dad went through a rather radical transformation in his later years. He became a kinder, gentler Don Conroy. What brought this about? Was it the death of your brother? The birth of grandchildren? The loss of his wife? It’s never quite clear in the book.

PC: I think it was a combination of those things, plus the fact that he just hated the way I had portrayed him in The Great Santini. I think he was determined to prove he wasn’t that guy. But, yeah . . . the loss of his wife, my mom, must have stunned Dad. It must have shocked him to the core. Because in Dad’s one-celled way – and Dad was a one-celled animal, and he was a blunt instrument – I believe he thought he was an exemplary father and husband. Providing for his children, clothing his children, educating his children . . . These were things his parents didn’t do for him – couldn’t do for him – during the Depression. So the fact that he did all these things for his kids – I think he truly believed he was a great father and husband. So when my mother left him, it must have stunned him.

But there was something else, too. I have noticed that the South changes people. No matter when they get here, it changes them. I saw Fripp Island retirees get friendlier the longer they lived there. They got comfortable, they loosened up. I think this happened to my father. Dad became an extraordinarily charming man later in life, and I think living in the South had something to do with it.

ME: Let’s talk about some other “southerners” who appear in this book – namely Beaufort locals. As I said earlier, I used to think you exaggerated some of your fictional characters – so many of them seem larger than life – but then I read this book and saw the way folks I know are portrayed, and those portraits are dead on. Let’s take Bernie Schein, for instance. You totally nailed Bernie. I howled laughing through every page on which he appears; I could literally see Bernie and hear his voice. So I no longer believe you exaggerate; I think you are simply drawn to “big” personalities . . . or maybe they are drawn to you.

PC: Thank you. I tell people I’m actually a shy minimalist, but they never believe me. So thanks for that.

ME: And I love the chapter about Big John Trask. I never knew him, but you make me wish I had. All the Trasks I know seem like such elegant, aristocratic people. But Big John sounds like something else entirely. I kept picturing Big Daddy from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

PC: Perfect. That’s a perfect description. I loved Big John Trask . . .

ME: In the book, you’re summoned for a command appearance before him after you’ve failed to attend a party thrown in your honor by his son.

PC: It was while The Great Santini was being filmed, and the party was given by John, Jr. and Caroline for Robert Duvall, Blythe Danner and me. I came home from Atlanta for this party, and I walked into a hornet’s nest. I walk into my mother’s house, and she’s at the kitchen table, bawling. Turns out she hasn’t been invited to the party. She’s devastated. My mom could be socially hurt worse than anybody I’ve ever seen; having grown up poor, she was so insecure about that stuff. So I go over to Freddie’s house to try to work this out – he was my best friend at the time, and John’s brother – and he hadn’t been invited to the party, either. Knew nothing about it.

ME: Maybe it was a very small party?

PC: It was huge.

ME: Continuing with this theme . . . George Trask was your lawyer when you fought the Beaufort County Board of Education after they fired you from your teaching job on Daufuskie, correct?

PC: Yeah, he was. And we walk into court on the first day, and he looks around and says, “Wow. This is really impressive.” I say, “What do you mean?” and he says, “This is my first case.” I say, “What?!?” (Laughs.) I had no idea. Anyway, we never really had a chance. I didn’t know it at the time, but the law said the superintendent could fire a teacher for any reason he wanted, at any time.

ME: You were fired for your unorthodox approach to teaching out on Daufuskie Island. Seems you took some liberties . . .

PC: Looking back, I can see I was a pain in the ass. But Daufuskie was hard. I was trying to do things like . . . well, teach the kids to swim. I figured they lived on an island; they needed to know how to swim.

ME: You didn’t like Jon Voidt’s portrayal of you in the movie Conrack, which was based on your book  The Water is Wide. In your new book, you call his performance “goofy and disconnected,” and you believe it was because Hollywood didn’t know what to make of a white southerner who was nice to black people.

The Water is Wide. In your new book, you call his performance “goofy and disconnected,” and you believe it was because Hollywood didn’t know what to make of a white southerner who was nice to black people.

PC: Yeah, they made him daffy. Kind of a Boo Radley figure. They just didn’t know what else to do with him, I guess . . .

ME: You write, “In the South, there were only fire-breathing white racists and wonderful, life-affirming black people.” This was the Hollywood stereotype in 1972. Do you think our image has changed since then?

PC: Well, with the rise of the Tea Party, I don’t know. I think our image has been set back a little.

ME: In the new book, you say you were very hurt by the fact that Penn Center didn’t support you during your trial, and in fact backed up the Beaufort County Board of Education.

PC: It was a big wound. Gene Norris used to take me out to Penn Center all the time, starting when I was fifteen. I met Martin Luther King, Jr. at Penn Center, and it had a huge impact on me. I even taught the first Afro American history course at Beaufort High. So, yeah . . . when I got fired in 1970, and Penn Center decided, as a political act, to support the black principal at Daufuskie instead of a white teacher (me), it hurt my feelings. I understood the decision, but it hurt. By the way, you’ll never find any of this in the Beaufort Gazette. They never reported on my trial. At all.

ME: You’ve got to be kidding?

PC: No. In fact . . . I was living in San Francisco 20 years later, in 1991, and I got a call from a young reporter at the Beaufort Gazette who wanted to interview me. She says, “Mr. Conroy, you have once again irritated the town of Beaufort. You are attending a premiere of The Prince of Tides in San Francisco, but are not attending the premiere in Beaufort, your home town, where the novel takes place.” I say, “Yes, what would you like me to say about that?” She says, “We wonder why you refuse to come to Beaufort, a town that’s given so much to your career?” So I say, “Let me introduce you to a little history. This is my first interview in the Beaufort Gazette in my whole life.” She replies, “I can hardly believe that.” I say, “You’re a reporter; you can look it up. And to answer your question, the reason I’m not coming to the premiere gala in Beaufort is because I wasn’t invited.”

ME: Well, you’ve certainly made up for your dearth of invitations and media attention since then. And speaking of media attention . . . In the new book you write: “I trained myself to be unafraid of critics, and I’ve held them in high contempt since my earliest days as a writer because their work seems pinched and sullen and paramecium-souled.” By the way, a critic could never have written that sentence.

PC: (Laughs) Shame on you!

ME: It’s true. But what I’m wondering is this: How much do ‘the critics’ mean to you at this point in your career? Their reviews of your work are often mixed. Do you care? Do you even read them?

PC: No, no . . . In fact, I’ve even gotten Sandra to quit reading hers. You know, there’s this thing people tell me about that just destroys writers. It’s called the Internet.

ME: You mean Amazon reviews? Where any Tom, Dick or Harry can write a review and post it for all the world to see?

PC: Yeah, stuff like that. And there must be dozens of them out there now . . .

ME: There are, and they’re full of reader reviews of Pat Conroy books. You’ve got such a tremendous, passionate readership, and they hang on your every word and never miss a book. What does that feel like?

PC: It feels great. I’m always surprised by it. You know, I’ve been very surprised by my whole career. Margaret, what are the chances of a guy like me having a career like I’ve had?

ME: A guy with your talent? Probably pretty good. A guy with your background? Maybe not as good.

PC: Yeah, I’m thinking of The Citadel. Not exactly a cradle of novelists . . .

ME: In The Death of Santini, you bid farewell to your mom and dad as literary characters. You write, “Mom and Dad, though I won’t come this way again, I hope that your strong souls rest in peace.” Do you really mean it? Are you truly done writing about your parents?

PC: Yeah, I think so. I think I’ve written about my parents more than anybody in American history. I don’t think there’s anybody close. Not even remotely.

ME: What have you been trying to do all this time?

PC: What I write for is this – I write to try to explain my own life to myself. Because it’s been very confusing to me. And I’ve noticed that life is confusing to almost everybody. You know . . . how we live our life, what we consider happiness . . . what does happiness consist of . . . All these things are very strange. We raise our children and hope we don’t screw them up. I said to my girls a long time ago, I said, “Girls, listen up – your mother and I are raising you and we’re doing the best we can, but we’re screwing you up. I don’t know how we’re screwing you up, but you’ll find out one day. So if you see me doing it, just ignore it.”

PC: What I write for is this – I write to try to explain my own life to myself. Because it’s been very confusing to me. And I’ve noticed that life is confusing to almost everybody. You know . . . how we live our life, what we consider happiness . . . what does happiness consist of . . . All these things are very strange. We raise our children and hope we don’t screw them up. I said to my girls a long time ago, I said, “Girls, listen up – your mother and I are raising you and we’re doing the best we can, but we’re screwing you up. I don’t know how we’re screwing you up, but you’ll find out one day. So if you see me doing it, just ignore it.”

ME: But do kids really “see us” screwing them up? With your dad, it was obvious, but it’s usually more subtle. And about your dad . . . he’s still a mystery to me. A cypher. I’ve read all your books, and now this one, and I still don’t understand his transformation. I can’t figure him out. I think maybe that’s because you never figured him out. You just learned to love him.

PC: Yeah. That still pisses Tim off.

***

Pat Conroy will be signing copies of ‘The Death of Santini’ at The Beaufort Bookstore in Town Center on Sunday, November 10th from 1 – 4 pm.

Margaret Evans is editor of Lowcountry Weekly

and writer of the regular column Rants & Raves.