Judith slaying the sleeping Holofernes investigated….The Haarlem painter Jan de Bray (1627–1697) painted the Biblical story of Judith slaying the sleeping Holofernes in 1659. After more than 350 years, De Bray’s depiction still deftly captures the determination on the heroine’s face and the unsuspecting tranquility of her slumbering foe, but other elements have been obscured over the ages.

The Rijksmuseum painting conservation studios hosts interns from conservation training programs all over the world. Gerrit Albertson is a student at the Department of Art Conservation at Winterthur/University of Delaware, USA. Read his blog on his experience in the first weeks of his internship at the Rijksmuseum here: https://www.artcons.udel.edu/news/Pages/Student-Blog-Rijksmuseum.aspx

In preparation for the conservation treatment of De Bray’s painting, the small, oak panel was examined using ultraviolet and raking light, stereomicroscopy, x-radiography, infrared imaging, and macro x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. These tools helped Gerrit with the interpretation of De Bray’s original intentions, and how these may have been altered over time by darkening varnish, degraded pigments, and previous harsh treatments, helping to inform his own treatment of the painting in the coming months.

One of the techniques used is Macro-XRF scanning, a relatively new technique where a very small X-ray beam is send to the painted surface. The surface, at the size of a pixel, is ‘excited’ by the beam and emits X-ray fluorescence radiation. This radiation is recorded by the Macro-XRF scanner. The specific amount of energy of this emitted radiation indicates the elements present in that particular spot. The Macro-XRF scanner moves the beam in scanning mode over the whole paint surface. This results in High Resolution images of the distribution of the elements in the painting, so-called elemental maps. The map of lead for example (Pb in the periodic table), indicates where the painter used a lead containing pigment such as lead white or lead-tin yellow.

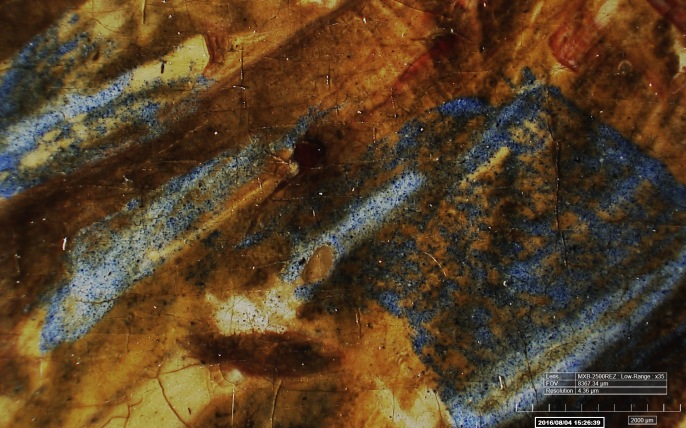

This elemental map of the De Bray, made using a Macro-XRF scanner, shows only the distribution of copper (Cu) in the highlighted areas, indicating the copper-based pigments such as green verdigris, in the painting. The map reveals intricate brushwork in the background drapery in the upper left corner, which is difficult to see in the actual painting. This is due to the darkening of the binding medium, most likely linseed oil.

Paintings often show traces of former treatments. Here a photomicrograph, made with a 3D Digital microscope (HIROX) at high magnification, shows how harsh treatments in the past may have abraded away some of the blue pigment in Judith’s scarf. The blue paint layer is very thin in places, or even gone altogether.

Removing a yellowed varnish layer, or layers, as sometimes a painted has been varnished more than once over a longer period of time, is a complicated task as the removal of any original paint should be prevented. To examine this, Gerrit performed some extensive testing of the solubility of the yellowed varnish layers, using a stereomicroscope to establish a safe and effective method for varnish removal.

Infrared reflectography is a technique which allows us to look through paint layers. The long wave lengths of infrared radiation can penetrate paint layers and reveal what is beneath. The amount of penetration depends on the thickness of the paint layers and the paint or drawing materials used, as some will absorb the infrared radiation while others will reflect it. Especially carbon containing materials, such as charcoal and black chalk or ink, often used for underdrawings, will absorb the infrared radiation. The infrared camera will capture the reflected light, which will show up from light grey to white, while the areas where the infrared radiation is absorbed will appear dark or even black. The resulting digital black and white image is a so-called infrared reflectogram. Depending on the absorption of the infrared radiation the reflectogram will reveal the layers of the painting that are otherwise not visible, such as underdrawings but also changes in the composition.

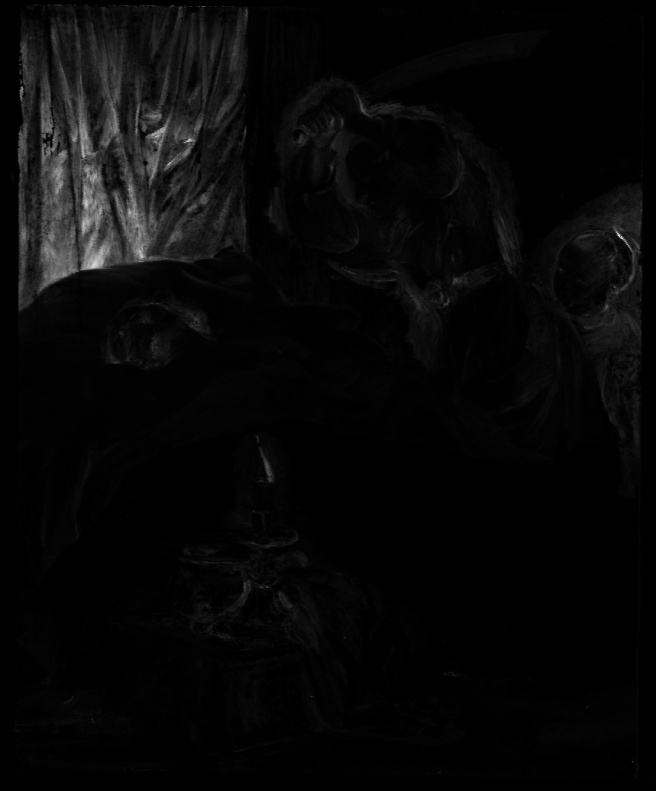

The infrared reflectogram presented shows that De Bray made a few changes in the composition as he worked; for instance, here you can see that Holofernes’ left hand, which was originally sketched in on his chest, was later painted over, and his right hand slightly shifted position.

Gathering all this information using a range of imaging techniques, tests, as well as discussions with colleagues, both conservators and curators, helped to make the right decisions on the treatment of the De Bray’s small panel, but also adds more information on the techniques and materials De Bray used.

Thanks to Gerrit Albertson.

Erma