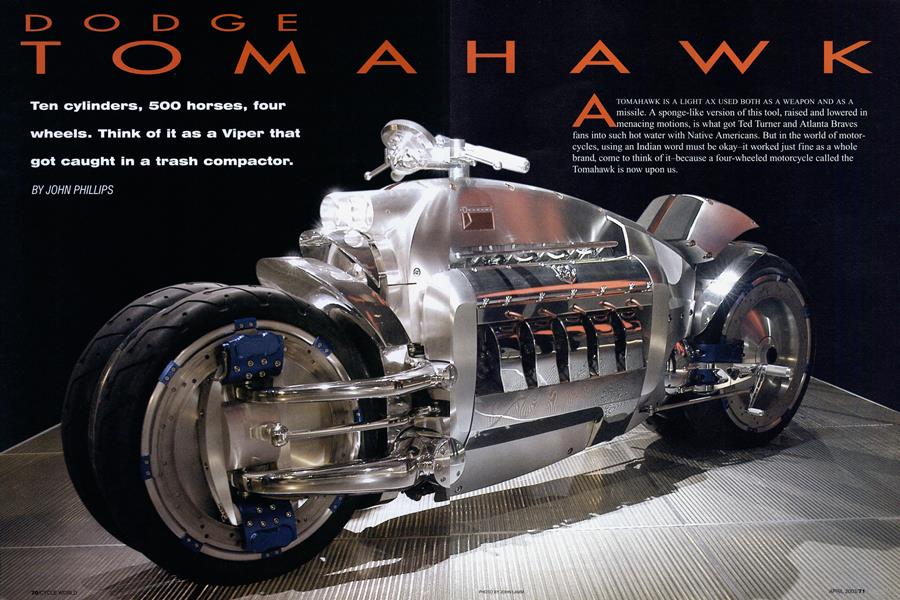

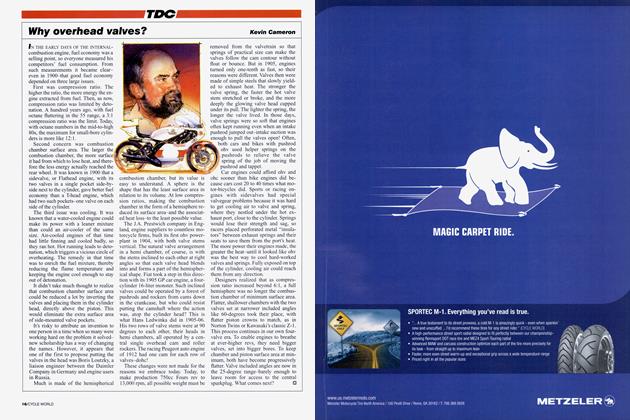

DODGE TOMA H A W K

Ten cylinders, 500 horses, four wheels. Think of it as a Viper that got caught in a trash compactor.

JOHN PHILLIPS

A TOMAHAWK IS A LIGHT AX USED BOTH AS A WEAPON AND AS A missile. A sponge-like version of this tool, raised and lowered in menacing motions, is what got Ted Turner and Atlanta Braves fans into such hot water with Native Americans. But in the world of motorcycles, using an Indian word must be okay-it worked just fine as a whole brand, come to think of it-because a four-wheeled motorcycle called the Tomahawk is now upon us.

During Cycle World's editorial meetings, here is something that Editor Edwards does not often say: “All right, guys, have we missed any road tests? Anything new from Triumph? From Victory? No? How about Dodge?”

Dodge? Doesn’t Dodge build minivans?

Well, yes. But Dodge also builds the Viper supercar, whose V-10 now produces 500 horsepower and more BTUs than half of the geothermal vents in Iceland. Thing is, folks are now over-familiar with Viper show cars, which have appeared in more variations than Anna Nicole’s Appalachian-like décolletage. And so, for the North American International Auto Show in Detroit this past January, there was interest in showcasing a Viper V-10 but without a lot of distracting plastic body panels and snake logos wrapped all around.

We’ll never know what dramatic possibilities were contemplated-perhaps a V-10-powered George Foreman grill, a Viper-motivated Hoover Elite upright vacuum, a 525-foot-pound Black & Decker paint mixer? What Dodge uncorked instead was a V-10-motivated motorcycle.

That’s right. Five hundred horses. Five hundred and five cubic inches. 8603 cubic centimeters. A 500-pound motor. Says the Tomahawk’s designer, Mark Walters, “All that oomph, it seemed like a good idea to give it two driven wheels.” Why also two wheels up front? This went largely unexplained. Symmetry, perhaps.

That and the years, American failed steadfastly citizenry has, to request for years such a device is not relevant to today’s discussion. It’s not clear who in America asked for a Cadillac pickup truck, either.

Last May, when Walters went looking for someone who could render his vision in aluminum, his boss, DaimlerChrysler’s Senior VP of Design Trevor Creed, recalled a 30,000-square-foot shop in Wixom, Michigan-the RM Corporation, an outfit famous for refurbishing Can-Am cars and, not incidentally, famous for refurbishing Creed’s own 427 Cobra. Which is how Kirt Bennett, 32-yearold vice-president of RM, got the job of assembling the planet’s very first Tomahawk.

“Mark showed me what Chrysler wanted it to look like, but 100 percent of the mechanical design was up to us,” says Bennett. “I’m not a motorcycle guy, so I went on a search for similar bikes-three, four wheels, any funky layout. But I couldn’t find anything that applied. Because of the bike’s weight (1500 pounds) and the length of the V-10, it was a mind-blowing packaging exercise. But that’s okay, we usually work on strange old McLarens, Lolas, Marches, things like six-wheeled Tyrrells. Over the years, you leam how guys solve odd problems. So I just went ahead and started inventing things.”

The first thing Bennett had to invent was a cooling package. In the Viper’s bulbous snout, of course, there’s room for a radiator the size of an NFL end zone. But with the Tomahawk, the only available space was in the traditional gastank area, essentially nestled in the engine’s vee. Bennett redesigned the intake runners to rise vertically and draw atmosphere through two jutting scoops just beneath the handlebars-making us wonder if the V-10 still produces 500 bhp. Nonetheless, this freed up enough room to insert a pair of 8 x 20-inch radiators angled in an upside-down V. They’re force-fed by a fan driven off the crankshaft.

Packaging dilemma #2: The V-10 is drysumped, and its 8-quart kidney-shaped reservoir had to be incorporated as part of the bodywork in front of the left valve cover. Small LED headlights and taillights were mounted between the front and rear sets of wheels-splash through mud at night and you’ll soon be riding blind.

The hand-made two-speed transmissiontransverse-mounted with dog ring and straightcut gears-feeds through a conventional 7.25inch double-disc clutch. Both rear wheels are driven by 110-link chains.

“I think they may have come from a forklift,” says Walters.

“Everybody worries about that small transmission handling so much wallop,” notes Bennett, “but the gears are the same we use in 600-horsepower F-5000 cars. Anyway, the safety fuse is the rear tires, which spin long before you’re putting a big load on the driveline.”

He should know. One night, when Chrysler COO Wolfgang Bernhard arrived to monitor the Tomahawk’s progress, Bennett performed an unbidden 30-foot burnout that continued right out the shop’s back door. “Man, just these two side-by-side black streaks,” he recalls, laughing. “Wolfgang is like, T don’t believe you just did that.’ We’re leavin’ the marks on the floor, like trophies-preserve them in urethane, maybe.”

The Tomahawk’s front suspension is approximately as complex as your average arms-reduction treaty-outboard, single-sided parallel upper and lower control arms made from billet aluminum, mounted via ball joints to aluminum steering uprights and hubs. At the rear are steel box-section inboard swingarms, located between the tires. There’s no frame to speak of. Everything bolts to engine plates.

Each outside 20-inch of the brake rims, rotor, is gripped attached by to two the four-piston calipers at the front and one four-piston caliper at the rear. In case you don’t have a calculator handy, that’s 24 pistons, which should ensure that Sunday-aftemoon brake overhauls extend right into Monday Night Football.

The question onlookers invariably ask first is, “Don’t the outside tires lift off the pavement in turns?”

“No, they don’t,” asserts Bennett firmly. “It’s an independent suspension, 2.5 inches of travel fore, 3.0 inches aft. The bike always thinks it’s on one wheel, front and rear." Creed tries to clarify: "If you put your open hands out in front of you, palms facing each other two inches apart, then twist them parallel, your little finger will always stay on the table. That's the principle." Of course, no one has yet leaned the Tomahawk into any curve except the one preceding the stage in Detroit.

Behind the front wheels is a snowplow-shaped fender that is hollow. It holds three gallons of fuel. In the street car, three gallons will get you almost to your mailbox.

What onlookers usually ask next is, "When you crack the throttle, doesn't the torque about twist the bike in half?" Responds Bennett, "It definitely rocks a few degrees, but the crankshaft is below the centerline of the wheels-a really low c of g-so it's nothing that'd toss you off the seat."

Creed wouldn't care it if did. "We meant it to be crude," he confesses, "like a chopper-not a bike you'd take to a track and race."

A t the unveiling, DaimlerChrysler digni taries resembled high school juniors in Mrs. Grinder's fourth-period study hail, conjuring all manner of performance possi Lilities. Zero to 60 mph in 2.5 seconds, they ager1y reckoned-i .4 seconds quicker than the Viper. lop speed? Well, here the speculation ran amok. "This engine and a 1-to-i drive ratio, with Dut factoring in aero drag, works out to 420 mph," theorized one Chrysler rep. Offered another, "If a 3400-pound Viper goes 190, this'll go 400, easy."

Really? We naturally volunteered to test this assertion, but had to withdraw when no 400-mphcapable trousers could be located. Asked one journalist: “Has anyone ever seen a wing-walker on a Boeing 747? No? Possibly there’s a reason.” The Tomahawk raises other awkward questions. For instance, if narrowing the track of a four-wheel vehicle eventually creates a motorcycle, would widening the track of a Roto Tiller eventually create a Humvee? Does anything with four wheels and 1500 pounds of heft even qualify as a motorcycle? Such inquiries perturb designer Walters not one whit. “The whole time we were working, I could hear the biker community in the back of my mind, saying, ‘Whoa, that’s not a bike.’ So?”

In fact, more than a few show-goers suggested that the Tomahawk is to vehicular commerce what the Hindenberg was to recreational ballooning. Not so. Parts of its bodywork can serve double-duty as a Tappan range hood. And it is sufficiently aluminum-intensive to attract interest from soft-drink bottling consortia nationwide. At the Detroit show a few years ago, Pontiac introduced a flamboyant concept car called the “Rageous.” Remarked an editor from the Detroit Free Press: “They should have called it the ‘Diculous.’”

Hold on. That’s too harsh, especially since the Tomahawk ceases being ridiculous the instant you clap eyes on all that jewel-like stainlesssteel and polished aluminum-a Georg Jensen jewelry exhibit on wheels. “We didn’t tool up stuff,” notes Bennett. “We’d just carve alu-

minum until we got what we wanted. The section under the seat began as a 750-pound billet. Now it weighs 25 pounds, max.”

If Dodge produces this hypercycle-further disturbing the psyches of those who own such conveyances as the Boss Hoss-the Tomahawk will likely fetch $200,000. Sure, that’s pricey, but remember that it stands upright all by itself, no need for a costly aftermarket kickstand. Of course, if the principal allure is simply the V-10, as Dodge is self-servingly wont to suggest, then why not buy an $85,000 Viper and throw away everything else? That would still leave enough cash to buy a Ducati 999 and a Ranger NASCARedition bass boat and part of a rain forest for Sting.

If the bike is produced, Dodge reckons it will be in “limited numbers.” We can guess what “limited numbers” means. It means two-the one that Jay Leno buys and the one that first lands in Dodge’s legal department.

Product-liability lawyer #1:

“Jim, did you check out this Tomahawk action?”

Product-liability lawyer #2: “I swear to God, Bob, you better be talkin’ about Ted Turner at a Braves game.”

It’s worth remembering that the Tomahawk’s main mission is to advertise an engine. An automobile engine.

“I still think we could do 100 copies or so,” asserts Bennett, “maybe even by ourselves, if Dodge doesn’t want to do ’em. A dozen guys already called here to say, ‘I’ll write a check right now.’” In fact, Chrysler has assigned RM Corporation to do more development on handling and cooling. “The first thing, though,” Bennett adds, “is to figure out how many wheels it should have.”

It’s ironic-or perhaps it isn’t-that the most publicized auto at the North American International Auto Show wasn’t an auto. Unfortunately for the Tomahawkers, Cadillac unveiled its own paean to one-upmanship a mere 50 yards away-a luxo sedan with a V-16 producing 1000 bhp. Twice the Tomahawk’s output. Which means-at least by Dodge’s amusingly convoluted logic-that Caddy’s engine could propel a bike to 800 mph. They could call it the Cadillac Flaming White Man’s Scalp.

Would this give us a shot at breaking the speed of sound on a motorcycle? Should someone notify Johnny Knoxville? □

For 28 years, John Phillips has written features for national magazines and is an Editor-atLarge for Car and Driver. This is his first story for Cycle World.