May 15, 2014

H.R. Giger, The Visionary behind “Alien,” Has Died

The dreary surrealist, who trained as an architect and industrial designer, was 74.

The nightmare is over for H.R. Giger. The pioneering artist, responsible for one of science fiction’s most famous on-screen monsters, died at age 74 Tuesday.

Pleasure principle and death drive formed a perfect unity for Giger, fused together. They were not, as Freud thought, mutually exclusive or opposites. Biomechanical and thanato-erotic themes pervade Giger’s work. Sometimes they appear organically in the composition of a single organism, as one undifferentiated mass of ferreous flesh. Other times they appear violently thrust together or torn apart, as in the penetration of all those quivering orifices by pipes and scraps of metal, or the epidermal extrusion of gears and wires. The night terrors that Giger suffered throughout his life, keeping him awake to all hours, are by now an integral part of his artistic body of work. Yet these alone are not enough to explain the deranged genius behind these disturbing, extraterrestrial images.

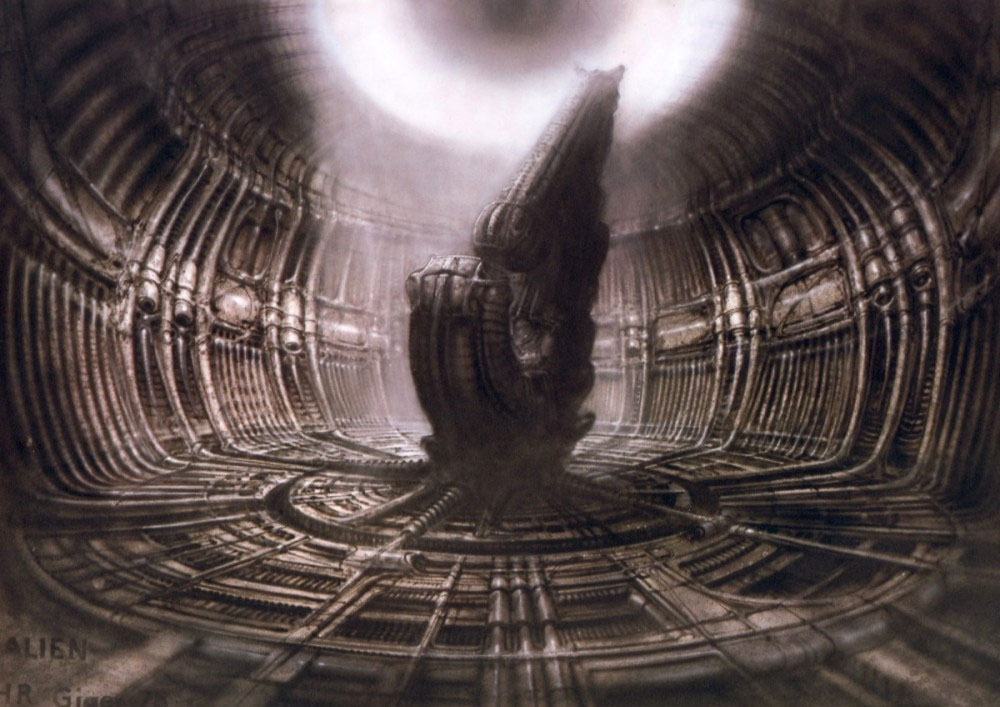

Like most of his fans, my first exposure to Giger’s unsettling vision of reality came through Alien (1979). It’s likely that he would have remained an obscure figure were it not for Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece. All the private obsessions that haunted Giger throughout his life were burned into the brains of millions of moviegoers. Not just the xenomorph itself, but all the accompanying artifacts as well. The enormous shipwreck in the shape of a wishbone, the undulating bionic walls of its interior, the fossilized remains of that elephantine creature strapped into a chair—its ribcage bent outward, having exploded from within. (Giger somewhat mysteriously dubbed it the “space jockey.”) Viewers caught a glimpse into the wasteland of his imagination, and have not forgotten since.

The Giger Bar in Gruyeres, realized based on the artist’s designs

Courtesy Amy Dianna via Flickr

At first glance there might seem nothing obviously “architectural” about Giger’s work, apart from the blasted landscapes and structures he was known to depict. It might surprise some readers to discover, then, that his formal training in Zürich during the 1960s was as an architect and industrial designer. This can hardly come as a shock to anyone who has seen the behind-the-scenes footage of Alien, however. Scott and Giger can be seen there erecting the massive interior of the derelict spaceship, almost two-thirds to scale. Children were placed into landing suits for the more grandiose shots in this sequence, in keeping with the proportions.

Beginning in the 1990s, moreover, Giger started to design a personal lair for himself and his wife in the Swiss metropolis, featuring numerous items from his inventory of diabolical creations. Weird functionless gadgets, a throne of sorts, and even a “garden of unearthly delights” are part of this estate. One can only imagine what an excavation of such a site would uncover. Fittingly, the rest of his collected corpus is housed in a medieval castle, the Château St. Germain, which Giger purchased in 1998 and now serves as a museum celebrating his creative output.

An unrealized design for the aborted film Dune.

Courtesy webodysseum.com

Of course, Giger had been at it long before Alien hit the box office. Some of the images that would later make up his Necronomicon series were exhibited at galleries around Europe before coming to the attention of the American painter Robert Venosa during the mid-1970s. Venosa introduced Giger to Salvador Dalí in 1977, after showing the aged surrealist part of the Necronomicon catalogue, released earlier that year. Impressed by the sense of metaphysical horror evoked by these pictures and the artist behind them, Dalí recommended Giger to the Polish filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, who was then busy assembling a dream team of artists and actors (including Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, and David Carradine, as well as the cartoonist Jean Giraud) to realize his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune. Jodorowsky immediately phoned Giger urging him to come on board.

Still relatively unknown, the Swiss designer eagerly assented. Unfortunately, the project foundered in the production process and much of the work never saw the light of day. Called by some “the greatest film never made,” it has received some attention lately thanks to a recent documentary by Frank Pavich (2013). Nevertheless, Giger was able to salvage some of the drawings he’d intended for Dune by reusing them for Alien, one of many subsequent movies spawned by Jodorowsky’s abortive space opera.

The iconic xenomorph from Alien.

Courtesy H.R. Giger

Fresh on the heels of Alien‘s success, Giger went on to create the cover for Debbie Harry’s solo album Koo Koo (1981). Later he’d team up with Glenn Danzig of Misfits fame to design the artwork for Danzig III: How the Gods Kill (1992). He also made some sketches for Alien 3 that were never used, but mostly lived off his celebrity status post-Alien. Collections of his work, such as Necronomicon and Erotomechanics (1979), continue to sell well, and will likely be reissued in light of his passing.

View of the cockpit of a spaceship from Alien.

Courtesy H.R. Giger

Comparisons have inevitably been drawn between the desolate worlds dreamt up by Giger and those envisioned by that other great dreamer, Lebbeus Woods, also recently deceased. In a 2012 issue of Art in America Aaron Betsky cited Giger alongside Leonardo, Piranesi, and Boullée as major forerunners of Woods’ baroque architectural delineations. Part of the association owes to their shared connection to the Alien mythos, no doubt, though their professional relationship to the series was quite opposite. (Woods worked briefly on Alien 3 as a “conceptual artist,” under the direction of Vincent Ward, but left the project after Ward was forced out. Later Woods would sue Twentieth Century Fox for using his designs without acknowledgement or compensation). There are, of course, numerous differences between the two. Giger’s style―often emulated but thoroughly inimitable―employed a much narrower palette of blacks, purples, and greens, whereas Woods was known for reds and yellows, as well as other colors across the spectrum. Yet there’s a common architectonic present in the work of both these artists, one grounded in the nightmarish recognition that modernity has gone awry. Somewhere between the parasitical modernism of Woods and the perverse industrialism of Giger lie the disjecta membra of twentieth-century architecture, which they assembled in various ways.

Ross Wolfe is a writer and historian of Soviet architecture currently living in New York. He blogs at The Charnel House.