The Original Code Talkers: U.S. Army Choctaw Code Talkers who served during World War I.

THE CHOCTAWS: WORLD WAR I

The use of Native Americans to transmit coded messages for the U.S. armed forces was a technique first developed during World War I as American troops were fighting in the trenches of the Western Front.

On April 6, 1917, the United States of America officially declared war against the German Empire. By that point The First World War had been raging for almost three years while the United States had maintained a policy of neutrality in hopes of avoiding the carnage that had engulfed Europe and the Middle East. The escalation of German Submarine attacks on American shipping and a German plot to forge an alliance with Mexico ultimately compelled the United States to enter the war on the side of the Allied Powers.

For over three years the Allies had been embroiled in a bloody stalemate with the Germans along the Western Front in Northern France and Belgium. One particular aspect of the war the Allies were losing was the battle against German code breakers. Not only were the Germans able to tap into Allied communication lines, but they were able to accurately intercept and decipher coded Allied transmissions. This provided the Imperial German Army with a distinct tactical advantage of gaining foreknowledge of Allied plans and operations.

In World War I the only way to communicate besides radio and telephone was to send soldiers out as “runners” to personally deliver messages from one unit to another. But this method was time consuming, it was wasteful of manpower, and too often runners would end up killed or captured. Carrier pigeons were also utilized to deliver written messages, but as with using runners, there was no guarantee that the pigeons would reach their destination in one piece. Radio and telephone were the most efficient ways for units to communicate on the battlefield, but to combat German code breakers a new way of communicating had to be developed.

During the fall of 1918, American troops from the 142nd Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division were stationed along the Western Front near St. Etienne, France. While walking through the trenches, an officer named Captain Lawrence overheard two soldiers speaking in what sounded like gibberish. Out of curiosity Captain Lawrence walked over and found that the voices he was hearing were two American Choctaw Indians, Solomon Lewis and Mitchell Bobb. The men happened to be speaking to each other in their old tribal language. Captain Lawrence realized that if he could not understand a word these men were saying then neither would the Germans.

Even in 1918, The Native American languages were as alien then as they were when Christopher Columbus had first landed in America over four hundred years earlier. Many of the Native American languages had never been written down or recorded, and to learn them was extremely difficult. There were nearly 1,000 Native Americans serving in the 36th Infantry Division representing twenty six different tribes from across the United States. The 142nd Infantry Regiment alone had several dozen American Indians within their ranks who spoke a multitude of different languages of which only four or five had ever been recorded.

After listening to Louis and Bobb, Captain Lawrence relayed his idea to Colonel Alfred W. Bloor, commanding officer of the 142nd Infantry Regiment. Lawrence brought the two Choctaw soldiers to the command post and told them “Look i’m going to give you a message to call into headquarters. I want you to give them the message in your language. There will be somebody there who can understand it”. Using a field telephone Mitchell Bobb relayed the Captain’s message to headquarters where it was received and translated by Ben Carterby, another Choctaw soldier who was brought in by headquarters. The Choctaws quickly and accurately translated the message proving Captain Lawrence’s concept. Working closely with other Choctaw soldiers, U.S. Army officers developed a new code based on their language replacing it with the standard code they had been using.

The new code was put to the test on October 26, 1918. While engaging the Germans near Chufilly, France during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Colonel Bloor ordered a tactical withdrawal of two companies to the town of Chardeny. The Choctaws relayed his orders using their coded language over telephones. From American observation, the Germans appeared to have been caught completely off guard by the maneuver. After the battle a captured German officer gave the Americans critical insight as to how well their new code worked. He told his captors that they had successfully wire taped American communications, however they were “completely confused by the Indian language and gained no benefit whatsoever”.

The Argonne Forrest, 1918: U.S. troops during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in Northern France. The Choctaw Code Talkers would play a critical role in several battles during this campaign.

Auteuil, France: A Choctaw Soldier wounded while serving on the Western Front receives treatment at a U.S. National Red Cross hospital.

After the success at Chufilly, Choctaws were placed as radio operators in other units, giving the Americans the ability to communicate and coordinate without worrying about the Germans ease dropping on their transmissions. The Choctaw Code Talkers would go on to participate in several successful engagements during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Even the most expert German code breakers were baffled by the Choctaw language as they were unable to gain any intelligence on Allied positions and movements.

Just days after pressing the Code Talkers into service, Allied forces had broken through German defenses in the Meuse-Argonne sector. The Allies had finally achieved a decisive breakthrough. On November 11, 1918; the guns on the Western Front fell silent. With their economy in ruins, their military decimated, and their allies Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria defeated, The German Empire agreed to an armistice with the Allied Powers, bringing an end to one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history.

November 11, 1918: U.S. troops celebrate after news of an Armistice is announced.

While the United States was only involved in the final year of the conflict, the Americans had helped turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies. After the war Colonel Bloor expressed with great satisfaction the role the Choctaws played in the conflict. He especially praised the ingenuity of the Code Talkers since there were no translations in the Choctaw language for certain military terminology, the Code Talkers improvised using alternate Choctaw words or phrases such as "Big Gun" for “artillery”, “little gun shoot fast” for “Machine Gun”, “Stone” for “Grenade”, and “Scalp” for “casualty”. The Choctaw Code Talkers in the 142nd Infantry also designated each battalion in the regiment one, two, or three grains of corn in their coded language. The beauty was that even a Choctaw speaker wouldn’t understand the meaning of the message unless they had a comprehensive knowledge of the Code.

Choctaw Code Talkers: A group of Native American soldiers who helped develop an unbreakable code based on their tribal language for the U.S. Army during World War I.

There were nineteen Choctaw servicemen officially recognized as Code Talkers by the U.S. Army during World War I; Albert Billy, Mitchell Bobb, Victor Brown, Ben Carterby, Benjamin Franklin Colbert, George Edwin Davenport, his half brother Joseph Harvey Davenport, James (Jimpson M.) Edwards, Tobias W. Frazier, Benjamin Wilburn Hampton, Noel Johnson, Otis Wilson Leader, Solomon Bond Louis, Peter Maytubby, Jeff Nelson, Joseph Oklahombi, Robert Taylor, Charles Walter Veach, and Calvin Wilson. All of whom were born in the Choctaw Nation; a semi-autonomous republic of the Indian Territory in what is now Southeastern Oklahoma.

At the time America entered World War I, the Choctaws weren’t even recognized as U.S. citizens. A number of Native American tribes had not been granted citizenship and were not entitled to certain privileges such as the right to vote. In many government-run boarding schools Native American children could be punished simply for speaking in their tribal language. Repressing Native American children of their language and culture was part of a long running government effort to assimilate American Indians into society. Despite years of discrimination, and subjugation, it is estimated that around 12,000 Native Americans had served in the U.S. Military during World War I, which was roughly a quarter of the male Native American population at that time. On June 2, 1924, all American Indians were finally granted US citizenship, partially in recognition for their wartime services.

While the Choctaws are regarded as the first Code Talkers, the first known use of the Native American language for coded military communications actually took place during the Second Battle of the Somme in September 1918. A group of Cherokee Indians serving with the U.S. 30th Infantry Division transmitted messages in their tribal language while under heavy fire. At the time the unit was under British command and little was mentioned about the event or the men who transmitted the messages.

Besides the Cherokee and the Choctaws, the U.S. Army recruited other Native American soldiers to serve as Code Talkers such as the Cheyenne, the Comanche, and the Sioux. Since the nature of their mission was regarded as a military secret, The Code Talkers were buried in the annals of history. They were largely forgotten and never given recognition for their services. However the incredible success of the Code Talkers would inspire the U.S. Military to develop new codes based on other American Indian languages.

THE MESKWAKI: MEDITERRANEAN THEATER WWII

February 26, 1943: U.S. troops maneuver through the Kasserine Pass in Tunisia. During the North African Campaign, it was the mission of the Meskwaki Code Talkers to recon these areas for enemy movement.

In January 1941, a group of twenty-seven Meskwaki Indians from Tama County, Iowa enlisted in the U.S. Army. At the time this group represented 16% of the Meskwaki population in Iowa. Assigned to the 168th Infantry Regiment of the Iowa National Guard, eight of the Meskwaki were selected to undergo training as Code Talkers. The soldiers accepted into the program were Edward Benson, Dewey Roberts, Frank Sanache, his brother Willard Sanache, Melvin Twin, Judy Wayne Wabaunasee, his brother Mike Wayne Wabaunasee, and Dewey Youngbear. After completion of basic training in Camp Dodge, Iowa, the Code Talkers were sent to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana to undergo intensive communications training and field exercises.

Like the Code Talkers in World War I, the Meskwaki came up with code words for military terms that didn’t have translations in their language, so they used words like “Hummingbird” as code for “Fighter Plane”, “Beaver” as code for “Minesweeper”, and “Race Track” as a code for “Half Track”. In October 1942, the Meskwaki Code Talkers rejoined the 168th Infantry Regiment and departed for Europe. After a brief stint in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the Meskwaki would get to take part in one of the first major American campaigns against the Axis Powers.

On November 8, 1942; the Allies launched Operation Torch, a joint British-American amphibious Invasion of French North Africa. Pro-Axis French forces in Morocco and Algeria collapsed quickly, while British troops led by Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery were advancing west through Libya. Pushed into Tunisia with their backs to the sea, German and Italian troops fought desperately to hold onto their last stronghold in North Africa. In Tunisia the Americans would have to face the battle hardened veterans of the German Afrika Korps who were commanded by the legendary “Desert Fox” Field Marshall Erwin Rommel.

Assigned to the 34th Infantry Division, The Meskwaki Code Talkers and the 168th Infantry Regiment landed in Algiers, French Algeria during Operation Torch. Vichy French troops either surrendered or joined the Allies, but Rommel’s Afrika Korps would prove to be a much harder adversary. Meskwaki Code Talker Frank Sanache described the deserts of North Africa as “the worst place this side of hell”. The fighting in Tunisia was bitter and bloody, as the inexperienced 34th Infantry struggled to make headway against The Afrika Korps. Throughout the North African Campaign the Meskwaki Code Talkers were utilized as scouts for the 34th Infantry. They would move out two miles ahead of American troops across hot and barren deserts reporting enemy movements. The Meskwaki would transmit messages in their tribal language which confused and frustrated the Germans. They provided critical battlefield intelligence for the U.S. Army but these dangerous missions would prove costly.

In February 1943, Frank Sanache was captured by German troops while scouting the Faid Pass near the town of Sidi Bouzid, in Central Tunisia. German Panzer Divisions had launched a surprise attack under the cover of a sandstorm and took the Allies completely by surprise. Allied forces were pushed back from Sidi Bouzid, leading to the Battle of the Kasserine Pass where the Afrika Korps inflicted heavy losses on inexperienced U.S. troops. Dewey Youngbear and Judy Wayne Wabaunasee would also end up captured by the Germans later on during the fierce battles in Central Tunisia. Their treatment at the hands of the Axis was a grueling experience. They endured exhausting manual labor, malnourishment, and in some cases beatings.

Dewey Youngbear made several escape attempts while he was a prisoner in Axis controlled Europe. During his third escape attempt he got his hands on an Italian Army uniform, which he was able to use as a disguise as he tried to slip out of Italy. Compelled by extreme hunger, Youngbear stopped at a local restaurant but was uncovered when he couldn’t understand or respond to German and Italian soldiers there. Youngbear, Wabaunasee, and Sanache would spend the rest of the war laboring in various POW camps across Europe. Despite their capture neither man gave their captors any information about the other Meskwaki or their codes.

Meanwhile back in North Africa, The remaining Meskwaki Code Talkers continued to aid the Allied war effort as the Axis forces were squeezed out of Tunisia. After the humiliating defeats at Sidi Bouzid and the Kasserine Pass, the Americans rallied back with renewed skill and determination. The Allies relentlessly pushed Axis forces into the Mediterranean. On May 6, 1943; Allied troops took Tunis and Bizerte, Erwin Romnel’s once vaunted Afrika Korps was all but broken. On May 13, all Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered.

From the fall of 1943 to the summer of 1944, the Meskwaki Code Talkers would take part in the Italian Campaign, serving with the 34th Infantry as they battled up the rugged Italian countryside against bitter German resistance. Code Talker Dewey Roberts recalled bitter memories of the Italian Campaign stating; “The 34th Division got chewed up. From Salerno to the Naples area we lost a lot of men. They were killed, wounded, and captured.” The Meskwaki Code Talkers handled critical battlefield communications for the 34th Infantry as they endured constant shelling and fought fierce battles as they advanced up the peninsula in a long and bitter uphill struggle.

On June 4, 1944, Allied troops had finally captured the city of Rome. For the small group of Meskwaki Code Talkers, the fall of Rome was the culmination of all their hard work. Their war was effectively over as they would soon return to their reservation in Iowa.

THE COMANCHES: EUROPEAN THEATER WWII

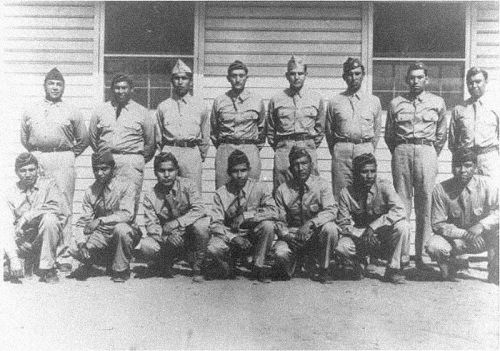

Fort Benning, Georgia: The Comanche Code Talkers; (Back row from left to right) Morris Sunrise, Perry Noyebad, Ralph Wahnee, Haddon Codynah, Robert Holder, Albert Nahquaddy, Clifford Ototivo, Forrest Kassanavoid, (Front row from left to right) Roderick RedElk, Simmons Parker, Larry Saupitty, Melvin Permansu, Willie Yackeschi, Charles Chibitty and Willington Mihecoby.

In December 1940, the U.S. Army recruited seventeen Comanche American soldiers to become Code Talkers; Charles Chibitty, Haddon Codynah, Robert Holder, Forrest Kassanavoid, Wellington Mihecoby, Perry Noyabad, Clifford Otitivo, Simmons Parker, Melvin Permansu, Elgin Red Elk, Roderick Red Elk, Albert Nahquaddy Jr., Larry Saupitty, Morris Tabbyetchy (Sunrise), Anthony Tabbytite, Ralph Wahnee, and Willie Yacheschi. All of the soldiers recruited were from the Comanche Nation in southwestern Oklahoma.

The Comanche squad was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, where they were assigned to the signal company of the 4th Infantry Division. Like the Code Talkers in World War I, the Comanches didn’t have translations for certain military terms, so they used letter and word substitutions as codes for certain terms. Together they came up with 250 coded words and terms such as "Tutsahkuna Tawo'i” (Sewing Machine), which was code for “Machine Gun”, “Wakaree'e” (Turtle), which was code for “Tank”, and “Po'sa Taiboo” (Crazy White Man), which was code for Adolf Hitler. They created an entire dictionary of code words covering every possible term from weapons, vehicles, to geographical features.

One problem that the Code Talkers had encountered was that they didn’t have translations for cities, towns, or villages, which could prove especially problematic when communicating on foreign battlefields. Fortunately they came up with an ingenious solution; they created their own alphabet which they would use common Comanche words to represent letters that they could use to spell out words in their coded language. At the time machines could transmit and decode a message in four hours, the Comanche Code Talkers could accomplish the same feat in three minutes or less.

Comanche Code Talkers assigned to the U.S. Army 4th Signal Company of the 4th Infantry Division.

On January 26, 1944; The Comanche Code Talkers embarked from Hoboken, New Jersey with elements of the 4th Infantry Division destined for Liverpool, England. The Comanches spent the next four months in Southern England rigorously training to take part in the Allied Invasion of Nazi-Occupied France. The 4th Infantry would be one of thirty nine Allied Divisions to take part in the Invasion code named Operation Overlord. In the early morning hours of D-Day, June 6, 1944; over 150,000 Allied troops came by air and sea across the English Channel destined for Normandy, France. The 4th Infantry was given the task of taking a three mile stretch of the Normandy coast codenamed Utah Beach. Each regiment in the Division was assigned at least two Comanche Code Talkers to handle strategic radio communications during the campaign. Landing craft carrying American troops pushed through the rough waters of the English Channel as they approached the target beach.

Hitting the shore the front ramps of the landing crafts dropped as the first wave of American troops stormed the beach. Shortly after landing, the Comanches went right to work sending and decoding messages. The first message from the Comanches on Utah Beach came from Code Talker Larry Saupitty, who transmitted the following message; “Tsaaku nunnuwee. Atahtu nunnuwutee” (“We made a good landing. We landed at the wrong place”). It turns out the current had pushed the landing craft off course and the 4th Infantry had landed a mile from their assigned targets. Ironically Saupitty was serving as radio operator for Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of late President Theodore Roosevelt, and deputy commander of the landing forces on Utah Beach. Saupitty was with General Roosevelt when he gave his famous order “This is as good a place as any to start the war. We’ll start right here”.

D-Day, June 6, 1944: U.S. troops of the 4th Infantry Division climb over the seawall after landing on Utah Beach in Normandy during the Allied Invasion of Nazi-Occupied France. The Comanche Code Talkers played a vital role in coordinating the logistical support for troops advancing inland.

What could have been a disastrous blunder turned out to be an inconvenience as U.S. troops overwhelmed beleaguered German defenders and pushed inland. All the while a small group of Comanche Indians were handling heavy radio traffic, relaying critical battlefield information in a rapid and efficient manner. Since American troops had landed in the wrong location, the Comanche Code Talkers coordinated the vital follow on support that helped the Americans advance inland during the first chaotic hours of D-Day.

During the Breakout from Normandy, the Comanches provided vital communications for the 4th Infantry when its troops captured the strategic town of St. Lo. In the coming months the Comanche Code Talkers aided the legendary U.S. Army General George S. Patton during his lightning offensive through France, culminating in the liberation of Paris on August 25. Allied forces advanced rapidly as the German Army retreated east, many started to speculate that the war could be over by Christmas. However resistance intensified as the Allies pushed towards Germany’s western border.

From November 7 to December 6, the 4th Infantry and the Comanche Code Talkers took part in fierce fighting in a rugged and heavily wooded area along the Belgian-German border known as the Hurtgen Forest. U.S. commanders hoped to push through the forest to the Rur River, but the battle that ensued was incredibly brutal and bloody. The Americans made little headway in the face of determined and skilled resistance. The Battle of the Hurtgen Forest resulted in 33,000 American and 28,000 German casualties. It was one of the bloodiest battles fought in Western Europe during the war. Exhausted from heavy fighting, the 4th Infantry Division was sent south to Luxembourg to get some much needed rest. The Comanche Code Talkers received no respite, they were put to work repairing damaged communication lines.

Just ten days after arriving in Luxembourg City, word got out that the Germans had launched a massive offensive that tore through under strength and inexperienced American units holding the Ardennes Forest further north. Led by elite Panzer and SS Divisions, the German Army launched their offensive on December 16 to coincide with a period of extreme winter conditions that would keep the Allied air forces grounded. Despite being exhausted, low on manpower, and fighting in near freezing temperatures, the 4th Infantry Division held its positions north of Luxembourg City in the face of the German onslaught. Comanche Code Talkers were once again hard at work relaying critical battlefield information trying to make sense of the chaos as American forces were caught completely off guard. The offensive created a huge bulge in the Allied line earning it the name “The Battle of the Bulge”.

January, 1945: U.S. troops maneuver through the snowy wilderness to drive the Germans out of Herresbach, Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. For the Comanche Code Talkers, this was their last major campaign of the war.

Ultimately the Allies were able to rally and stop the Germans far short of their objectives. An Allied counter-offensive crushed the Bulge by January 25, 1945. While the Allies had suffered heavy casualties, Hitler’s desperate gamble to break the Allies had nearly broken the German Army. For the Comanche Code Talkers the Battle of the Bulge would be their last major engagement of the war. In the spring of 1945, Nazi Germany was invaded from the east and west, culminating in the unconditional surrender of all German forces on May 8, 1945. Amazingly not a single Comanche Code Talker had been killed during the war.

THE NAVAJO: PACIFIC THEATER WWII

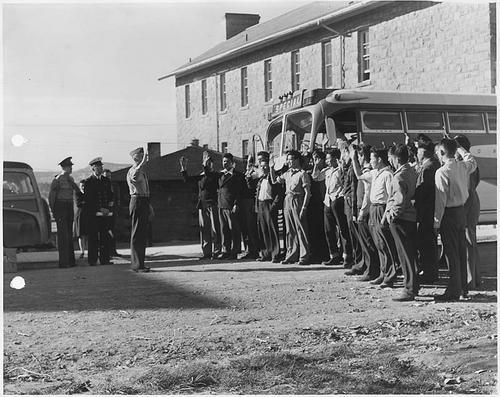

Fort Wingate, New Mexico, 1942: The first Navajo Code Talkers are sworn into service with the United States Marine Corps.

In Los Angeles, California just days after the United States entered World War II, civil engineer and World War I veteran Philip Johnston read in the paper about the U.S. Army training Comanche Indians to serve as Code Talkers. The idea inspired Johnston as he believed that the Navajo Indians could also be utilized in the same manner. As the son of a Christian missionary, Johnston grew up in Flagstaff, Arizona where his father worked on the nearby Navajo Reservation. As a child Johnston played with Navajo children on the reservation where he learned to speak their tribal language. He was one of only a handful of Americans who could fluently speak Navajo. Johnston recruited four Navajos working in Los Angeles to help prove his theory and he presented the idea to the United States Marine Corps.

On February 25, 1942, Johnston and the Navajos arrived at Camp Elliot in San Diego, California, to demonstrate the viability of the Navajo language as a military code to the top brass of the U.S. Marine Corps. Using standard military field phones, the Navajos were able to transmit and decode a three-line message in twenty seconds when machines at that time took a half hour to accomplish the same task. Marine officers were so impressed by the demonstration that they soon began a Navajo Code Talker program.

On May 4, 1942; the first batch of twenty-nine Navajo recruits boarded a bus from Fort Defiance, Arizona destined for the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego. Some of the young Navajo had never even set foot off the reservation before. In San Diego they would endure seven weeks of basic training to become Marines. Know as Platoon 382, they became the first all-Navajo unit in the U.S. Military. After completing basic training on June 27, Platoon 382 was sent to Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California where they would undergo further training in the communications.

The Navajos created and perfected a code using substitutions for Military terms that didn’t have translations in their language, such a Chay-da-gahi (Tortoise) which was Navajo code for “Tank”, Be-al-doh-tso-lani (Many Big Guns) was code for “Artillery”, Be-al-doh-cid-da-hi (Sitting Gun) was code for “Mortar”, Tsas-ka (Sandy Hollow) was codeword for “Bunker”, and Ni-ma-si (Potato) was codeword for “Grenade”. As the war progressed new terms were added to the Navajo Code, such as Jay-sho (Buzzard) which was codeword for “Bomber Plane” and Besh-lo (Iron Fish) which was codeword for “Submarine”. They also created their own alphabet which they could use a certain word that represented a letter and use a sequence of words to spell out a code word. The Navajo Code Talkers memorized all their terms and codes, then they practiced transmitting and decoding messages rapidly under the most stressful conditions which they could accomplish in three minutes or less.

Eventually around 400 Navajo Indians would become Code Talkers in the United States Marine Corps. Unlike the Germans, the Japanese had almost no experience dealing with American Indians, and the U.S. Military knew this. They also knew that many within Japanese Military Intelligence had been educated in the United States and were able to break every code that the Americans were using. So the Navajo Code Talkers were deployed to the Pacific where they would put their unique skills to use against the Empire of Japan.

On August 7, 1942; U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands chain, just northeast of Australia. Guadalcanal was of great strategic importance for both sides. The Japanese were in the process of constructing an airfield on the island. If completed, Japanese aircraft could threaten to cut off supply routes from the United States to Australia and New Zealand. But In American hands the airfield could give the Allies a strategic base of operations to drive the Japanese out of the South Pacific.

While the landings were unopposed and the Marines took the airfield without much opposition, the Japanese launched a major counter-offensive to regain control of Guadalcanal. The U.S. Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy engaged in fierce clashes around the Solomon Islands, while the Marines and the Japanese endured nightmarish conditions in what would be one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific Theater.

Guadalcanal, September 1944: U.S. Marines patrol the Matanikua River. Guadalcanal was the first battle involving the Navajo Code Talkers during World War II.

Like other Native American Code Talkers, the Navajo were extremely critical in coordinating U.S. forces by relaying tactical battlefield information. In his first action of the war, fellow Marines were pinned down in the jungle by Japanese machine gun fire, Code Talker Chester Nez transmitted the following message in Navajo code over the radio; “Beb-na-ali-trosie a-knah-as-donih ab-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi.” A fellow Code Talker listening in received and decoded the message; “Enemy machine-gun nest on your right flank. Destroy”. Within seconds after sending the message, American artillery accurately destroyed the Japanese emplacement without causing any harm to fellow American troops.

In similar engagements across Guadalcanal the Navajo Code Talkers were proving to be a valuable asset to the Marines. Even under the most stressful conditions with gunfire and explosions going off around them, the Navajo Code Talkers were widely commended for their speed, accuracy, and efficiency. One Marine sergeant who fought on Guadalcanal stated “If it was not for the Code Talkers, we may not have been able to take the island”. The Japanese were absolutely baffled by the voices they were hearing over the radio, they couldn’t tell what they were saying. Thanks to the Navajo Code Talkers, an untold number of American lives were saved, and the Japanese gained absolutely no intelligence listening onto Marine communications.

Guadalcanal, November 1942: U.S. Marines inspect a bunker for signs of Japanese troops. Navajo Code Talkers were vital in helping to pinpoint Japanese defenses and accurately directing American fire support.

After six months of brutal jungle warfare, U.S. forces secured Guadalcanal on February 9, 1943. It was a major strategic victory for the Allies in the Pacific as they would use the island as a base of operations to retake the Solomon Islands. But on Guadalcanal a disturbing incident had occurred that would plague the Navajos periodically during the war.

A number of U.S. troops had mistaken the Navajos for Japanese. Native Americans shared certain physical characteristics that were considered Asian in nature. Some thought the Navajos were Japanese spies or infiltrators. One such incident had occurred not long after the Code Talkers had arrived on Guadalcanal.

“I got captured by my own men. We were waiting out on the beach and the army was coming in. They put a gun to my head and took me to the Provost Marshal. And the Provost Marshall said I don’t want the Jap, go shoot him. And the Sergeant, he said, “Well, he’s got a Marine Corps thing on there, and he talks good English.” The Provost Marshall said, “That don’t make any difference, let’s shoot him”. But just then I say, “My outfit is down there". Finally they sent me back to my outfit. I had 15 men around me and a gun pointed to my head. I got down to the beach and I got back to my outfit, where they were sitting around playing cards and the sergeant says, “Is this your man?” And one guy, his name was Bonner says, “Yeah, he’s one of our men.” “And so they got me back and they got this guy, Charlie, Charlie Woods or Charlie somebody to watch me. They gave me him as a bodyguard. And I went everywhere. I go everywhere and he came right behind me.”

- William McCabe, Former Navajo Code Talker, USMC.

In order to prevent further incidents, a fellow Marine would be tasked with guarding Navajo Code Talkers to make sure that they weren’t unnecessarily detained or shot at by American troops who might mistake them for Japanese. These Marines were also to ensure that the Navajo were not captured by the Japanese since the code was considered of great strategic importance. Despite some incidents of discrimination, the Navajos would continue to serve with great distinction throughout the war.

July 7, 1943: PFC Preston Toledo and PFC Frank Toledo, Cousins and Navajo Code Talkers serving with the Marine Corps in the South Pacific.

On June 30, 1943, American-led Allied forces began a series of offensives in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea with the aim of encircling Rabaul, the main Japanese base in the South Pacific. The Navajo Code Talkers took part in some of the fiercest fighting with the Marines throughout the Solomon Islands including Bougainville, where pockets of fanatical Japanese troops waged a bitter guerrilla campaign against Allied troops until the end of the war. Meanwhile further north, U.S. forces were preparing for another major offensive against the Japanese.

The first target for U.S. forces in the Central Pacific was an airbase located 2,400 miles southwest of Hawaii, on Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands. The capture of Tarawa would give the United States a base to launch offensives further west against the Japanese in the Marshall Islands. On November 20, 1943, the Americans launched a massive air and naval bombardment of Tarawa in preparation for the Marine landings. At 9am that day the Marines began their assault. The Navajo Code Talkers went in with 2nd Marine Division rocking back and forth in the Higgins boats unsure of what to expect when they hit the beach. All they could see was fire and smoke coming from the tiny island which had been turned into a hell on earth by the naval bombardment. Things soon went terribly wrong.

To their horror the Marines found that the tide was too low, and the Higgins Boats got caught up in the coral reefs, forcing the Marines to disembark in shallow water 500 yards from the beach. The Marines struggled to wade through the shallow tide with full combat gear while taking heavy fire from Japanese defenders. Only the tracked landing vehicles known as “Alligators” made it past the coral reefs onto the beaches but they were unable to break through the sea wall.

Navajo Code Talker Jerry C. Begay Sr. was riding on an Alligator that ran into a pier and was disabled by enemy artillery. While under heavy fire, Begay found himself helping wounded Marines on a beach that was becoming a scene of unspeakable horrors. The dead and wounded littered the sands of Tarawa, the rotten smell of flesh filled the air, and the tide turned blood red. Machine guns, snipers, artillery, and mortars took a heavy toll on the Marines as they fought their way ashore.

November 20, 1943: The Battle of Tarawa. Painted by Tom Lovell, USMC retired.

Tarawa, November 1943: An American LVT “Alligator” disabled on the beach by enemy fire.

Tarawa, November 1943: A Navajo Code Talker on a radio directing logistical support and American fire support for advancing Marines.

Alligators were ferrying Marines stranded on the Coral Reefs onto the beach, but many of the tracked landing vehicles were being disabled by intense enemy fire. Attempts to bring in tanks onto the beaches floundered as landing craft were getting hung up on the reefs or were getting hit by enemy fire. Despite everything that had gone wrong, by noon the Marines had established a small beachhead and were able to penetrate the first line of Japanese defenses. Of the 5,000 Marines that went ashore that first day, 1,500 were dead, wounded, or missing.

All the while the Navajo Code Talkers were working tirelessly under the worst conditions coordinating naval fire support and follow on logistical support for the Marines as they pushed forward. It took two more days of savage fighting but by November 23, Tarawa had fallen. The fanatical Japanese garrison had fought to the last man. Only seventeen soldiers and 129 labour workers were taken prisoner. The aftermath was horrific; 4,690 Japanese were killed along with 1,696 Americans over a tiny little patch of sand in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Many within the military and back home in the United States were questioning, “Was it worth it?”. But according to U.S. Marine Corps Colonel Joseph Alexander; “The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific”.

Ten weeks later U.S. Air forces on Tarawa provided critical support for American troops during the Marshall Islands Campaign. Unlike Tarawa, the Marshall Islands fell far easier and U.S. forces were much better coordinated. Tarawa had provided the Marine Corps and the Navy vital lessons that would prove critical in the coming battles.

In the summer of 1944, the 2nd Marine Division and its Code Talkers were back in action ready to take part in the Marianas Campaign. The key objectives were the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. If taken, U.S. forces could gain strategic air and naval bases that they could use as a staging point for the upcoming campaign to liberate the Philippines. Most importantly the airfields in the Marianas would put American B-29 bombers within range of Japan, including the capital city of Tokyo.

At 7am on June 15, 1944; the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, along with their Navajo Code Talkers invaded Saipan after U.S. forces had spent the last two days bombarding the island by air and sea. Despite fanatical Japanese resistance and heavy losses from artillery, the 2nd and 4th Marines managed to secure a beachhead and push inland.

Saipan, June 1944: (From left to right) Cpl. Oscar B. Gallup, PFC Chester Nez, and PFC Carl Gorman. Navajo Code Talkers were praised by Marine Corps leaders for their role in the Battle of Saipan.

During the Battle of Saipan, the Navajo Code Talkers impressed U.S. military commanders for rapidly and accurately directing naval and artillery gunfire. The Navajos ability to coordinate fire support for the Marines was critical in taking the island. Beyond the beaches the Japanese were well dug into the mountainous terrain of Saipan. Heavy fighting raged as the Americans struggled to dislodge the Japanese from their underground fortifications. Parts of Saipan earned dubious nicknames such as “Hell’s Pocket”, “Purple Heart Ridge”, and “Death Valley” as U.S. forces relentlessly drove the Japanese to the northern end of the island.

July 8, 1944: U.S. Marines take cover behind an American M4 Sherman while clearing the Japanese from their defensive positions on Saipan.

On July 7, the last remnants of Japanese defenders launched a suicidal “banzai” charge that went on for fifteen hours. The Americans suffered heavy losses, but the Japanese were all but wiped out. On July 9, the island of Saipan was finally secured by the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. It was the bloodiest battle of the war at the time. Over 29,000 Japanese had died, along with over 3,400 Americans and 22,000 civilians. Not long after, U.S. Marines launched successful amphibious assaults on Guam (July 21- August 10) and Tinian (July 24-August 1). While Saipan was a brutal battle, many Americans would not have survived had it not been for the Navajos.

Throughout the war, the Japanese were continuously frustrated by the Navajo Code Talkers and while they had broken the U.S. Army and U.S. Air Corps codes, they were still not able to break the U.S. Marine Corps codes. Japanese Military commanders became so desperate they were brutally interrogating U.S. POW’s of Navajo descent. One such Prisoner was Sergeant Joe Kieyoomia, a U.S. Army soldier from New Mexico who was serving with the 200th Coast Artillery unit defending the Philippines during the Japanese Invasion on December 8, 1941. Sergeant Kieyoomia was one of 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners who endured the infamous “Bataan Death March”. Later on he would experience appalling conditions on a Japanese prisoner transport dubbed “Hell Ships” by allied captives. Laboring in a POW camp in Nagasaki, Japan, Sergeant Kieyoomia was suddenly questioned about the Navajo Code Talkers.

While he was able to translate the messages that were recorded, he was just as confused as the Japanese. The messages were a disjointed series of words and sentences that made no sense except to a trained Code Talker which Kieyoomia was not. His translations were therefore useless. He repeatedly told his captors he did not know the meaning of the code, but they didn’t believe him. He was stripped naked and taken outside on a cold winter day and forced to stand outside barefoot in the snow until he could reveal any useful information about the code. When Sergeant Kieyoomia was finally given permission to return to his cell after an hour in the snow, he found that his feet were frozen to the ground. When the guard shoved him, the skin on the bottom of his feet tore off. Prison Guards continued to beat Sergeant Kieyoomia on a daily basis during his time in captivity. Amazingly he also survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki because he was protected by the concrete walls of his jail cell. He spent three days locked in his cell alone until a Japanese officer finally freed him and the war ended soon after. Joe Kieyoomia passed away on February 17, 1997, and is currently buried in Farmington, New Mexico. He proudly use to boast “I salute the Code Talkers, and even if I knew about their code, I wouldn’t tell the Japanese”

On September 15, 1944; the 1st Marine Division and the Navajo Code Talkers began landing under heavy fire on the beaches of Peleliu, an island located 500 miles east of the Philippines. Instead of throwing everything they had to stop the Marines on the beaches, the Japanese dug into the rugged terrain of the island, creating an elaborate system of bunkers and underground fortifications. This allowed the Japanese to conserve their strength while forcing the Americans to launch costly frontal assaults against heavily fortified defensive positions. The result was a grueling war of attrition which both sides suffered heavy losses. U.S. commanders originally believed that Peleliu would be captured in four days, but the battle lasted for two months. Peleliu was secured on November 27, but by that point over 1,500 Americans had died along with nearly 11,000 Japanese. The 1st Marine Division was severely mauled suffering 6,500 total casualties, over one third of the division’s total strength.

Peleliu, September 1944: U.S. Marines fighting to clear Japanese defenses while under heavy fire on Peleliu.

For the Navajo Code Talkers serving with the Marines, Peleliu was a nightmarish experience. Over 150,000 mortars had been fired during the battle, and it took an average of 1,500 rounds of artillery to kill each Japanese soldier defending the island. The amount of fire power the Americans had to expend to subdue the enemy was mind boggling. While the island and its airfield played little significance in the Philippines Campaign, The Battle of Peleliu did provide the Code Talkers and the U.S. Military with critical lessons about the deadly new defensive tactics employed by the Japanese.

The next target for U.S. forces was a tiny volcanic island called Iwo Jima. Located just 750 miles south of Tokyo, Japan, Iwo Jima was a desolate island, but the three airfields located there was of great strategic importance. If captured, the U.S. Army Air Force could use Iwo Jima as an important base of operations where they could bombard Japan in preparation for an Allied invasion. Iwo Jima was Japanese soil, and the Americans knew that the enemy would defend their home territory with zealous ferocity. By this point Japan’s only hope was to inflict as many casualties on the Americans as possible so that hopefully the Allies would cancel plans to invade the Japanese home islands and negotiate for peace. Japanese troops began constructing a complex network of underground fortifications turning Iwo Jima into a fortress. The U.S. Navy and Army Air Force relentlessly pounded the island by air and sea for over eight months in an effort to soften Japanese resistance for the coming assault.

February 19, 1945: After a massive pre-invasion bombardment, American landing crafts surge forward towards the beaches of Iwo Jima.

On February 19, 1945; U.S. Marines landed on Iwo Jima. Amongst the thousands of Marines landing on the island were six Navajo Code Talkers. Hitting the beach the Marines expected to come immediately under heavy fire, but instead they were greeted with an eerie silence. The Marines cautiously advanced forward, and then all hell broke loose. It turned out that the Japanese underground fortifications were too well entrenched and too well camouflaged to be affected by the American bombardment. Despite months of unrelenting air and naval attacks, Iwo Jima’s defenses were barely scratched by the time the Marines landed. The Japanese simply waited until the beaches were congested with Marines, supplies, and equipment before unleashing a devastating barrage of machine gun, sniper, artillery, and mortar fire from well concealed defensive positions.

February 19, 1945: U.S. Marines under heavy fire after landing on the island of Iwo Jima. In the foreground is Mount Suribachi, an extinct Volcano which was a key Japanese defensive position on this island fortress.

Corporal Merrill Sandoval was a Navajo Code Talker serving in the 5th Marine Division during the Battle of Iwo Jima. Many years later Sandoval could still recall vivid memories of the chaos he and other Marines endured that day;

“We had to climb down these large cargo nets hanging over the edge of the ship to get down to our landing crafts. As I was going down, I slipped and fell into the landing craft.

Once we were all loaded into the landing craft, we had to wait for our order to go in. As we waited, we circled the Tennessee. I remember it was a large battleship. When we finally got our order, I remember the mortar being fired above our heads from both directions, from the battleships and from the Japanese on the island.

As we approached the edge of the island we did not come in squarely, so our landing craft tipped over. We lost all our equipment, including a jeep. I had the radio equipment with me, but I had to let it go and swim ashore. There were already a lot of dead Marines all around.

The island was a volcanic island, so the shore was not like a beach. It was a steep drop off like a cliff. We had to climb up out of the water and try to find cover the best we could. The ground was hard, so we couldn’t dig fox holes.

We were pinned down with the Japanese firing down on us from Mount Suribachi. I remember seeing our planes strafing the mountain and some of them didn’t make it. I remember thinking I was watching a movie and couldn’t believe I was really there. We had to make our way over three inclines before we were finally able to dig in. This was near the Japanese airfield. It took us 3 days to regroup”

- Merrill Sandoval, Former Navajo Code Talker, USMC.

Despite heavy casualties, the Marines kept pushing forward, and reinforcements kept landing on the beach despite withering enemy fire. Like Saipan and Peleliu, the Marines had to methodically clear out enemy fortifications using grenades and flamethrowers. Amazingly the Marines found the Japanese popping out behind them and reoccupying bunkers that were just cleared. To their shock the Marines discovered that the Japanese had built a sophisticated network of underground tunnels throughout the island connecting their defenses like a giant ant colony. Progress was slow and painful, but with each bloody foot inland the Marines were able to overwhelm Japanese defenses by sheer numbers. 30,000 U.S. Marines had landed on Iwo Jima that day, and another 40,000 would follow later.

Using radios and walkie talkies, the Navajo Code Talkers directed a massive arsenal of American firepower against enemy positions. The Navajo were also coordinating the flow of troops, supplies, and equipment swarming the beaches. During the first two critical days of the battle, the Navajo Code Talkers transmitted and decoded over 800 messages without error. Not a single one of those messages could be deciphered by the Japanese.

By the end of the first day, the Marines had cut off Mount Suribachi from the rest of the island. On February 23, after four days of savage fighting, Mount Suribachi had fallen, culminating in the iconic image of the Marines raising the U.S. flag over the Iwo Jima. During the Battle for Mount Suribachi, the Code Talkers relayed coordinates of Japanese defenses from Marines on the front lines to the Navy and Air Force. Air strikes and naval artillery accurately pounded Suribachi’s defenses thanks to the Code Talkers.

February, 1945: The U.S. flag over Iwo Jima after the fall of Mount Suribachi. The Navajo Code Talkers played a vital role in helping the Marines overcome the seeming impregnable defense on Suribachi.

With the Southern end of Iwo Jima secured, the Marines pushed north capturing the airfields. The terrain was extremely rocky, and Japanese defenses were just as formidable as Suribachi. Inch by bloody inch the Marines took Iwo Jima, and the Navajo Code Talkers followed close behind directing air strikes and naval gunfire which took a heavy toll on the battered Japanese defenders who resisted to the last man. Navajo Code Talker Samuel Tso recalled one of his most harrowing experience fighting on Iwo Jima.

“When I ran across that Death Valley, I ran into a whole bunch of Marines who got shot down trying to cross that valley. Some were still alive, and they reached out to us to ask for help. But the sergeant was right behind us and said, "You’re not supposed to do that kind of duty, you’re supposed to locate the machine-gun nests and report back. That is your mission.” So we didn’t have time to help anybody out, we just kept going and we located a couple of them (enemy positions).

Just to keep the machine guns silent, we threw some hand grenades close by the machine-gun nest. And we found out it’s not an open nest, it’s an enclosed nest, and there’s just a slit where they were firing from. Even though we hit the enclosed nest, the hand grenade bounced off and exploded outside. But then that was just to keep their heads down until we crossed back across the valley and report, and we did report, and that’s when one of the Navajo Code Talkers sent a message and ordered artillery fire, mortar fire and rockets.

While he was sending over there, and I was over on the other side, the sergeant chewed me out. Oh, he really got after two of us who stopped and tried to help those wounded Marines. And when they finished sending the message, within about five minutes, they started shelling and (dropping) all that bombardment on that machine-gun area, they just literally blew everything up. I don’t know how many minutes it took them.

When they stopped firing, they ordered the Marines to cross it, and the Marines just walked across that valley. So those machine guns were all knocked out. That was toward the end of the Iwo Jima operation.“

- Samuel Tso, Former Navajo Code Talker, USMC.

The Navajos worked nonstop around the clock until Iwo Jima was finally captured on March 26. It was one the bloodiest and fiercest battles of the war. The Americans suffered 26,000 total casualties including 6,800 killed while over 18,000 Japanese had died including 3,000 who chose to commit ritual suicide instead of being captured or live with the shame of defeat. Only 216 Japanese were taken prisoner. While it had come at a heavy cost, Iwo Jima became a key base for the Air Force bombing campaign against Japan.

The role that the Navajo Code Talkers played in the Battle of Iwo Jima was recognized by the highest echelons of the U.S. Marine Corps. The Signal Officer of the 5th Marine Division, Major Howard Connor stated "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima”.

After a long and bloody island hoping campaign across the Pacific, by the spring of 1945, American-led Allied forces were at the doorstep of the Japanese Home Islands. With the fall of Iwo Jima there was only one final island U.S. forces had to capture before a full scale Allied Invasion of Japan could commence. Located just 400 miles south of Japan, was the island of Okinawa. With its strategic naval base and airfields, If Okinawa could be captured it would be the staging point for the planned Allied invasion of Japan. As the last line of defense to the home islands, the Japanese were planning to put up the fiercest fight that U.S. troops had ever encountered.

April 1, 1945: U.S. Marines land on the Island of Okinawa in the largest amphibious invasion of World War II.

On April 1, 1945, U.S. Army and Marine Corps units landed on the western coast of Okinawa. Expecting a bloodbath, the Americans were surprised that they faced no resistance landing on the beach. The strategic airbases at Kadena and Yomitan were captured within hours after the landings. Cautiously advancing inland U.S. troops pushed across the narrow island cutting it in half with little opposition. While the Marines were tasked with clearing the Northern end of the Okinawa, two U.S. Army Divisions pushed to clear out the Southern end of the island. Everything up to that point had been too easy. But on April 4, Okinawa suddenly turned into the bloodiest killing field of the Pacific.

In the south the U.S. Army ran into a heavily fortified series of defenses centered on the historic Shuri Castle. The Americans suffered 1,500 casualties taking “Cactus Ridge” and “The Pinnacle”, but they soon realized that they had only scratched the outer perimeter of the Shuri Line.

By the end of April, the Marines were redeployed to reinforce battered Army units still trying to break through the Shuri Line. The sheer intensity of the fighting was overwhelming, driving even the most battle-hardened Marine to the breaking point. As they had done throughout the war, the Navajo Code Talkers did their best to support their Marine brothers by directing airstrikes, naval gunfire, artillery, rockets, and mortars against Japanese defenses. Former Navajo Code Talker Roy Hawthorne recalled one of his most harrowing experiences on Okinawa when his unit was pinned down by heavy enemy fire, and his radio was damaged during the fight.

“We encountered a force that was superior in manpower and firepower, and so we were pinned down for a couple of days at least. That was the time the antenna on my radio was shot off.

We were trained in a number of areas of communication, and one of those was field wire, so we’d always have some field wire with us and the tools to work with it, like pliers and cutters and stuff like that. So I was fortunate enough to put that back together. At least for a temporary fix to get a message out. So we got a message out for an air strike. And they showed up in just a little while and saved the day.”

- Roy Hawthorne, Former Navajo Code Talker, USMC.

Okinawa, May 1945: U.S. Marines watch as a Japanese Bunker is destroyed by demolition charges.

Progress along the Shuri Line was slow and bloody as U.S. troops methodically used artillery, dynamite, grenades, and flamethrowers to flush out Japanese defenders from their caves, tunnels, bunkers, and pillboxes. As May came to a close, monsoon rains had turned the island into a muddy quagmire. It was a miserable experience as troops struggled through the mud, and the dead from both sides were left rotting and half buried in the muddy ground.

Okinawa, 1945: A group of Marines cautiously probe caves along a hillside for hidden Japanese troops.

After nearly two months of heavy fighting, Shuri Castle was finally captured by U.S. Marines on May 29. While the Shuri Line was finally broken, the Japanese only withdrew to their last line of defense on the Kiyan Peninsula. The final battle on Okinawa was a slaughter of horrific proportions as U.S. troops launched costly frontal assaults against formidable defenses, while the Japanese were determined to fight to the death despite a massive bombardment of American firepower. Pushed into the southernmost corner of the island the last remnants of Japanese resistance were exterminated on June 21, 1945, but amazingly isolated pockets of Japanese guerrillas continued to resist until the end of the war.

The Battle of Okinawa was the bloodiest battle of the Pacific Theater far surpassing casualties of any previous engagement. The U.S. Military suffered 82,000 total casualties including over 12,500 killed or missing. Over 110,000 Japanese had been killed, and estimates regarding the deaths of Okinawan civilians range from 40,000 to 150,000. In total roughly a quarter of a million people had died in the Battle of Okinawa. Many feared that if so many had to die for this tiny little island, how many would be lost in the Invasion of Japan. Thankfully it would never come to that.

On August 6, 1945; the U.S. Army Air Force dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki. Both cities were wiped out and roughly a quarter of a million people were killed. On August 15, 1945; the Empire of Japan agreed to surrender unconditionally to the Allied Powers. On September 2, 1945, a Japanese delegation signed the instrument of surrender on the deck of the American Battleship U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay, officially bringing an end to World War II.

The Navajo Code Talkers had seen action in the bloodiest battles of the Pacific Theater; Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Tarawa, Saipan, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. The Navajo Code Talkers returned home to their reservations in the American southwest where they were hailed as heroes by their people.

The U.S. Military kept the Navajo Code as a closely guarded secret for use in future conflicts. Navajo Code Talkers were again utilized in smaller numbers during the Korean War in the 1950s and in the early years of the Vietnam War in the 1960s. The Code Talkers would wait many years before the nature of their missions came to public light and many more years before they were given recognition for their service.

RECOGNITION

October 28, 2009: A group of former U.S. Marines and Navajo Code Talkers visit the World War II Iwo Jima Memorial in Washington D.C. (From left to right) Keith Little, Peter MacDonald, Frank Chee Willetto, and Bill Toledo.

During World War II, the U.S. Military utilized Native Americans from eighteen different tribes as Code Talkers including the Cherokee, Cheyenne, Choctaw, Creek, Comanche, Hopi, Lakota, Meskwaki, Navajo, and Seminole. They were amongst 25,000 Native Americans who had served in the Second World War. The exploits of the Code Talkers during World War II were kept secret by the government, the military, even the Code Talkers themselves. Even the families of the Code Talkers knew little to nothing about what their loved ones did during the war. According to Navajo Code Talker Chester Nez;

“When we got out, discharged, they told us this thing you that you guys did is going to be a secret. When you get home you don’t talk about what you did; don’t tell your people, your parents, family, don’t tell them what your job was. This is going to be a secret; don’t talk about it. Just tell them you were in the service, defend your country and stuff like that. But, the code, never, never, don’t mention; don’t talk about it. Don’t let people ask you, try to get that out of you what you guys did. And that was our secret for about 25, 26 years. Until August 16th, 1968. That’s when it was declassified; then it was open. I told my sister, my aunt, all my families what I really did”.

When the U.S. Military declassified the Navajo Code Talker Program in 1968, the public finally learned about the important role that Code Talkers had played in World War II. Finally the veterans were allowed to speak and tell their stories to their families, their tribe, and a grateful nation. The public’s interest grew in the Navajo Code Talkers, and slowly the achievements of other Native American Code Talkers came to light.

In 1982, the Navajo Code Talkers were awarded a certificate of recognition for their vital contributions during World War II. President Ronald Reagan declared August 14, 1982 “Navajo Code Talker Day”. On September 17, 1992, the Pentagon opened an exhibit dedicated to the Navajo Code Talkers. Thirty five Navajo veterans attended the ceremony where they witnessed the exhibit featuring photos, equipment, and a comprehensive overview of the code they created. On December 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton signed a law awarding the original twenty nine Navajo Code Talkers with the Congressional Gold Medal and Congressional Silver Medals for all Navajo Code Talkers who served in World War II.

After nearly seventy years, the Choctaw Code Talkers of World War I were finally given their long overdue recognition when the Choctaw Nation posthumously awarded the Choctaw Medal of Valor to the families of the nineteen Code Talkers in 1986. On November 3, 1989, the French government presented the Chevalier de I'Ordre National du Merite (Knight of the National Order of Merit) Choctaw Code Talkers in honor of their valiant defense of France during World War I. In 1995 the Choctaw War Memorial was built in Tuskahoma, Oklahoma at the Choctaw Capital Building with an inscription reading the names of the Choctaw Code Talkers.

In 1989, the same year France honored the Choctaw Code Talkers, the French government awarded the Chevalier de I'Ordre National du Merite to the Comanche Code Talkers for their service in liberating France from Nazi Occupation during World War II. Three surviving Comanche Code Talkers who attended the ceremony; Charles Chibitty, Roderick Red Elk, and Forrest Kassanavoid were honored. Amazingly the French honored the Comanche Code Talkers long before the United States government had done so. On November 30, 1999; the United States Department of Defense honored Charles Chibitty at the Pentagon with the Knowlton Award which recognizes significant achievements in Military Intelligence. During the ceremony, a tearful Chibitty commented “I always wonder why it took so long to recognize us for what we did… they are not here to enjoy what im getting after all these years. Yes, it’s been a long, long time”.

Chibitty was the last surviving Comanche Code Talker of World War II. He was a decorated veteran who participated in the battles at Normandy, St. Lo, The Hurtgen Forest, and the Battle of the Bulge. Amongst his multitude of awards was a cavalry officers Sabre given to him by the Comanche tribe which in their culture is equivalent to the Medal of Honor. He became a chief amongst his people, sharing with younger Comanches his war stories, memories of his fellow code talkers, and taught the Comanche language to other Americans. On July 20, 2005, Charles Chibitty died in a hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma after a long battle with diabetes. The old chief was 83 years old.

Charles Chibitty (November 10, 1921- July 20 2005). A decorated veteran and hero amongst his tribe, Chibitty was the last Comanche Code Talker of World War II to pass away.

Of the eight Meskawaki Code Talkers who served in World War II, Frank Sanche was the last to pass away. He had endured five months of grueling fighting in the deserts of North Africa, and two years languishing as a Prisoner of War. He was eighty six years old when he passed away on August 21, 2004. He is currently buried in a tribal cometary in Tama County, Iowa. Sadly the Meskwaki never lived to receive any recognition for their contributions in World War II. However their families would finally receive the great honor that many like them had long waited for.

On November 15, 2008, President George W. Bush signed the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008, recognizing all Native American Code Talkers who had served during both World Wars awarding the families with the Congressional Gold Medal. For many of the families who had fought so long for the recognition of their relatives services, it was a bittersweet moment. Dozens of Indian tribes and nations were honored with Congressional Gold Medals which were uniquely designed for each specific tribe and the Code Talkers who represented their people. The men who had served so honorably and courageously as Code Talkers have become a source of great pride amongst their tribes. They used the very language of their people and their ancestors to help defeat America’s enemies in two World Wars. While so few of the Code Talkers remain today, their stories of honor, loyalty, and courage have continued to serve as inspiration, and they have come to define the Native American people.

Ocala, Florida: A plaque dedicated to the Navajo Code Talkers at the Florida Memorial Park.

"I found out I was fighting for all the Indian people. All the people in the United States, all what we had, as we call the United States. I found out this is what we were fighting for. From whoever try to take over us”.

- Samuel Tso, Former Navajo Code Talker, USMC.

© Daniel Ramos 2013. This is a summarized chapter from the book, Unsung Americans: Minorities at War by Daniel Ramos. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written consent of the author.

indigeraptor reblogged this from militarywiz

indigeraptor liked this

militarywiz posted this