Once a month, John Cobb stops by Evergreen Cemetery in East Oakland to check on the Jonestown Memorial. Eleven of his family members are buried there, including his mother and five siblings. He’ll sit on the bench, contemplating those he lost, or get to work wiping away the acorn shells and foxtails on the granite memorial plaques he helped put in place over a decade ago.

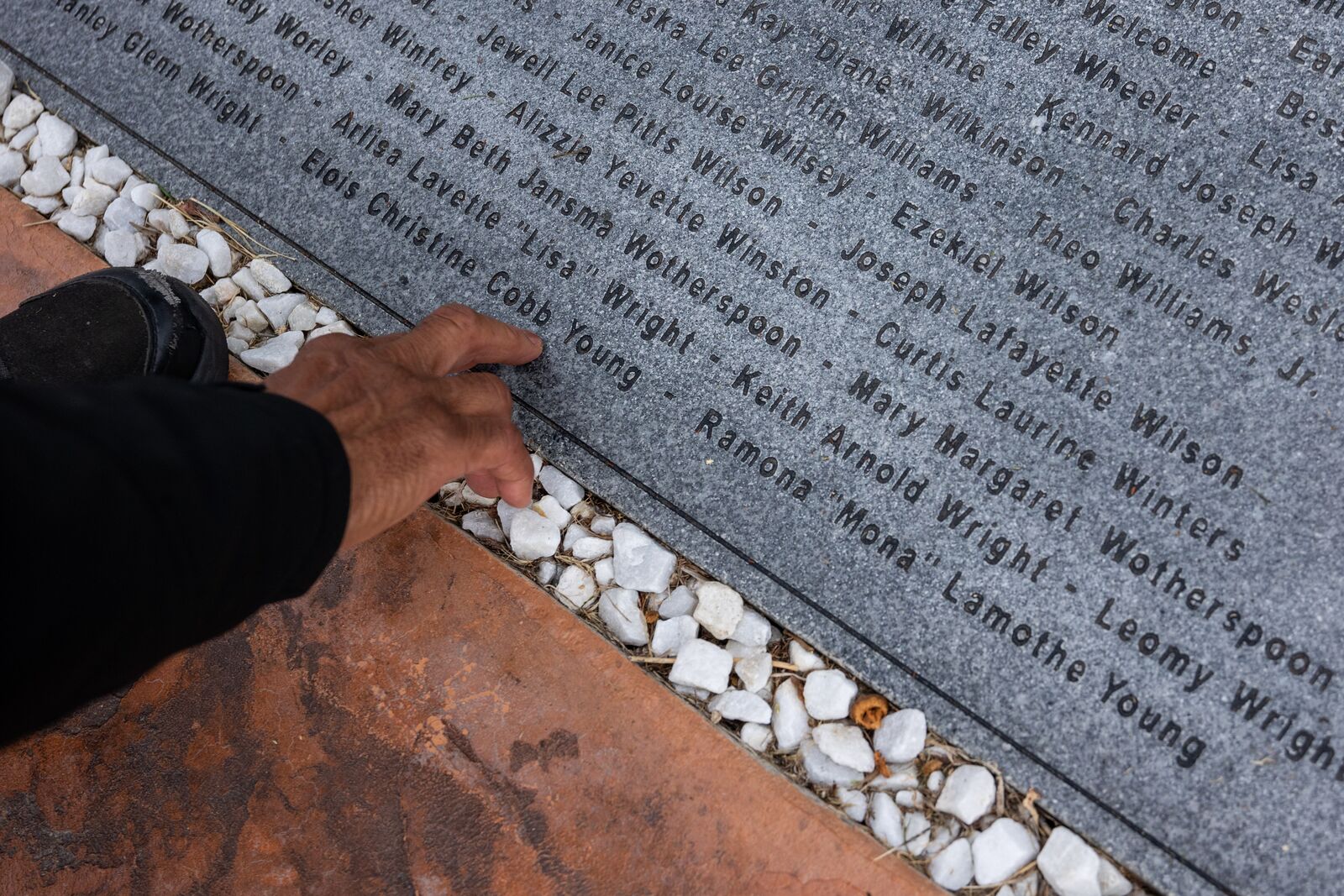

The memorial exists to ensure the stories of his loved ones aren’t forgotten. It sits on a half-moon-shaped hill in the cemetery, which is located just below MacArthur Boulevard between 64th and 68th avenues, overlooking the Coliseum in the distance. The memorial is remarkably humble — four plaques with 918 engraved names of the Peoples Temple members who died 45 years ago — and belies how big Jonestown has loomed in the collective imagination.

Cobb lives near the memorial and now runs a furniture business. But when the Jonestown tragedy happened, he was 18 years old and part of Jim Jones’ personal security detail in Guyana. Jones started Peoples Temple church in the 1950s, first in Indiana then San Francisco, championing racial equality during a time of overt segregation. It ended with him using drugs, paranoid in a “promised land” he called Jonestown in the interior jungle of Guyana, where he forced death on members via poisoned Flavor Aid and gunshot. Over a third were under the age of 18.

When Cobb is at the memorial, reading the names, his memories are nothing like the horrific images from Guyana that flooded the media in the days that followed. What he sees are ordinary moments of ordinary people: Sharon “Tobi” Stone, who said little but hit that cowbell hard in Cobb’s R&B band, Black Velvet; Free movie tickets for the kids in the hands of Patty Cartmell, who could talk her way into anything; Marceline Jones’s love of burnt toast.

It’s been said, but Cobb feels it hasn’t been said enough: They weren’t “mindless victims mesmerized by a cult leader.” They were people who’d lived through Jim Crow, emerging scarred and exhausted, wanting more equality and less discrimination. A world where access to healthcare, education, and food was possible without struggle — and without racism.

More than three-quarters of Peoples Temple members were Black; nearly half were women and girls. When Cobb recalls why his mother Christine joined, leaving the Midwest to come to California, the word he continually uses is “brave.” She had seven kids and believed Peoples Temple was a community where her children could have a good life, a belief shared by many of the members.

As a child, Cobb would participate in non-violent rallies and protests alongside social justice luminaries like Angela Davis, Dennis Banks, and Cesar Chavez. They marched for farmworkers’ rights, housing solidarity, and racial justice. He sees little difference between then and now, and talks about the members’ commitment to creating an alternative way of living in Jonestown with pride.

“The reasons they went there and things they were trying to change are some of the same exact things going on today,” he said.

On the day of the tragedy, in 1978, Cobb was playing point guard in a basketball game against the Guyanese national team in the capital city of Georgetown. The last person he heard from was his sister, Sandy, who’d worked as a nurse in the medical facility at Jonestown and called him over the radio. When Cobb asked what was happening, she said: “I just love you, Johnny.” It was the last communication he heard.

When he talks about it, he doesn’t shy away from the regret he’s learned to live with. “I could’ve stopped it,” he said.

Stigma shrouded Jonestown. The Guyana government refused to keep the bodies and sent them back to the United States, where the remains of over 400 unclaimed members stayed at the Dover Air Force base in Delaware for six months until Evergreen Cemetery owner Buck Kamphausen offered to give them a final dignified resting place. No other cemetery would.

Kamphausen, who’d taken over Evergreen in 1971, had watched the tragedy unfold on the news. “It became more and more clear that a lot of people were captive and had gotten sucked into this deal,” he said.

He felt sorry for them, and realized he could excavate a rundown, sloping hill behind the crematorium to make room for a mass burial –- an area within the cemetery that at the turn of the century excluded Black people, who had to be buried across the street.

Kamphausen bought concrete burial boxes, and started with the children. The whole process took about a month.

“It’s been a healing place for a lot of people,” Kamphausen said. “There are very few cemeteries that have something like this.”

Evergreen Cemetery already had some notoriety. Thousands of people who died from the 1918 flu pandemic are buried there, as well as Hell’s Angels riders and the original Buckwheat from the TV show Little Rascals. It’s also where Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton was cremated.

“If you think about Oakland’s rich history of civil rights, it’s fitting that it’s here,” Cobb said, referencing the Jonestown Memorial. “It worked out the way it should have.”

Before each anniversary, Cobb makes an extra effort to ensure the memorial shines. He picks the surrounding weeds, polishes the granite, and buys flowers. He also replaces the white rocks that form a border around the names because the birds take them to reinforce their nests.

The rest of the year, it’s quieter. Yet visitors continue to trickle and Cobb often finds objects near the plaques: coins, flowers, figurines, seashells. He’s always meeting people who are curious, and says what’s changed over the last four decades is their openness to learning the whole story.

Cobb himself wasn’t always so open. For nearly three decades, a lone gravestone put in place by the Guyana Emergency Relief Committee marked the spot and read: “In memory of the victims of the Jonestown tragedy.” A picturesque eucalyptus tree towers over it and remains to this day.

Survivors and loved ones gathered every Nov. 18 to pay their respects and enjoy the camaraderie with each other – but for the first 10 years, Cobb didn’t attend. He was more recognizable as a survivor when he was younger, he said, so would go to the memorial in the morning by himself before the barrage of press arrived.

“Back in the early years, people would find out and go, ‘Are you serious? That shit was crazy.’ without thinking of your feelings,” he said. “So you pretty much shut it all off to live.”

He opened his furniture business, got married, and had a daughter who knew nothing about his past because her mother didn’t want her mired in controversy. But when she was a freshman in high school, she learned about Jonestown in class—including some erroneous information about the community. She came home to her father and said, “Those people were crazy! They believed in aliens and spaceships!”

That’s when Cobb knew it was time for her to know his truth. She cried, and he held her like a father does, feeling her pain.

Afterward, he began talking more publicly about what happened and felt an obligation to formalize the memorial, after an earlier attempt by others to do so had been unsuccessful. In 2011, he along with his stepbrother Jim Jones Jr. and Fielding McGehee formed the Jonestown Memorial Committee and raised $15,000 for the plaques in three weeks.

It was important to the committee to list everybody’s names who died at Jonestown, as well as their nicknames. Congressman Leo Ryan and four others who traveled to Guyana to intervene and were shot and killed on an airstrip just prior to the massacre were also listed. James Warren Jones, too. A group of Los Angeles survivors protested his inclusion but the committee believed it was a matter of historical record.

Kamphausen put in the funds to raise and flatten the hill so people could walk to the memorial without wobbling. They continued to come back year after year, and some began a tradition of going to Harry’s Hofbrau in San Leandro afterward. The number has dwindled as people have gotten older and passed away, but a few members requested to be buried near their loved ones and currently rest around the perimeter.

“I hope when people come, they walk away with a different understanding of the people here who died. That in spite of everything they’ve heard and read, they were a group of people who wanted to create a better place to live.”

John Cobb

Cobb, 63, is one of three original members still living who was born into the church. The awareness of his mortality is what motivates him to keep showing up. “Once we’re gone, that history is gone,” he said.

Some of the older Peoples Temple members still call him “Little Johnny Cobb,” and there isn’t a day that goes by where he doesn’t think about that time. But the good parts. Whenever an old song plays on the radio — “Best of Our Love” by The Emotions or “Mona Lisa” by Nat King Cole — he’s right back to memories of his mother and sisters, dancing.

Cobb says he’ll keep tending to the memorial as long as he’s “six feet above ground” — and now welcomes talking to others about his experience at Jonestown. He’s also working on a memoir, For Them, driven to “tell the stories of those who can’t tell it themselves.”

He says the story of Jonestown is a sad one, no doubt. But it’s also a courageous one.

“This history is in our backyard. I hope when people come, they walk away with a different understanding of the people here who died. That in spite of everything they’ve heard and read, they were a group of people who wanted to create a better place to live,” Cobb said. “And maybe that opens up something in themselves.”

One day at the memorial, a pair of 30-something-year-old friends from nearby Auburn visited. The women had watched every documentary and listened to every podcast about Jonestown, and Cobb spent some time talking to them about his family, pointing out his mother Christine’s name. He thanked them for paying their respects. “I saw you saying a little prayer,” he said. “It was so nice and so attentive.” They’ve since kept in touch, and Cobb has an invitation for them to reach out, anytime.

The Jonestown Memorial 45th anniversary gathering will take place this year on November 18 at Evergreen Cemetery at 2 p.m. All are welcome.