July 7, 2015 Photo by: Hamish Brown

The Chemical Brothers' last major outing was 2012's Don't Think, an unusual concert film collaged together from the perspectives of multiple gobsmacked audience members—a strobe-lit, jump-cutting jolt that put a point on the duo's ecstatic two-decade career. "It felt like the culmination of a lot of years' work," says Tom Rowlands. "I suppose, after we made the film, you could have said, 'That's it, they've done their thing.'"

But calling it quits wasn't in the cards, even though fellow Brother Ed Simons is now increasingly occupied with his academic career, the details of which he prefers not to divulge. ("'Non-specific academic work' is the phrase he's very keen on," says Rowlands.) In fact, Simons will sit out the group's upcoming live shows, in which Rowlands will be accompanied by Adam Smith, their longtime visuals partner. But the pair still DJ together on a fairly regular basis, and Rowlands can be found in his London studio pretty much daily. That's where he and Simons spent the better part of the last three years working on their eighth album, Born in the Echoes—not just woodshopping their sound, but rethinking the purpose of the entire project.

"When you first start out, you make a record and you go on tour, and you're just in that cycle," says Rowlands. "But at this point, we have to make something that feels vital, something that we couldn't not make. A lot of time was spent experimenting and finding a vibe."

They got their first intimations of that vibe as they began perfecting "Sometimes I Feel So Deserted", a white-knuckled, peak-time anthem that does pretty much none of the things that peak-time anthems are supposed to do: There's hardly any kick drum, there's no real bassline, and the drops are actually anticlimactic, building to a frenzy and then pulling the rug out, leaving the listener hanging in midair. Nevertheless, the exhilaratingly uneasy track became a staple of their DJ sets, in part because it sounded so different.

"It was a conscious decision not to make that track so pumped-up—it felt more like a like band playing techno music, but with their instruments not quite plugged in," says Rowlands. "It's exciting for us when we can make a record that doesn't sound like another club record but still gives you that response when we play it in the club."

Fittingly, Born in the Echoes contains some of the duo's most effective club cuts in years: "Just Bang", a gnarly house bruiser that sounds like the bastard child of Ron Hardy and the Bomb Squad; "EML Ritual", a seasick acid-house burner featuring the high-strung crooner Ali Love and a battery of rushing 909 snares; and "Reflexion", a pitch-bending instrumental that wails like a five-alarm fire in a synthesizer factory. Rowlands calls the album's tougher cuts "instinct records—they're not trying to be everything to everyone."

These subwoofer-stretchers are just part of the album, though. Elsewhere, St. Vincent plays an ice princess on the shuddering "Under Neon Lights", and Beck drops his guard on the melancholy "Wide Open". There are '60s-inspired psychedelic rave-ups and odd, radiophonic sketches; in my estimation, the spooky and slippery title track, featuring Cate Le Bon, is one of the best things they've ever written.

And then there's "Go", the album's first big single, complete with a quirky Michel Gondry video. The song's a quick-stepping hip-house joint that finds Q-Tip riding a boisterous, Technicolor-soul chorus. It's not my favorite song on the album, but I can imagine hearing it on a car stereo 10 years from now and being supremely stoked. Rowlands laughs when I tell him this.

"It's one of those things that some people love, and other people just go, 'Ugh, that doesn't sound like the Chemical Brothers,'" he says. "But to me it really sounds like where we started, mixing hip-hop and synthesizers together. If I were going to a friend's house and there was going to be dancing and fun, I'd want that record in my bag."

He imitates the beat, singing the hook through the phone. "Some people don't want to go down that road—whoa-oh, ba da da da da da da da—but that's the bit I always sing. This record is about trusting what you feel, going with what makes you feel good, and not worrying what people will make of it."

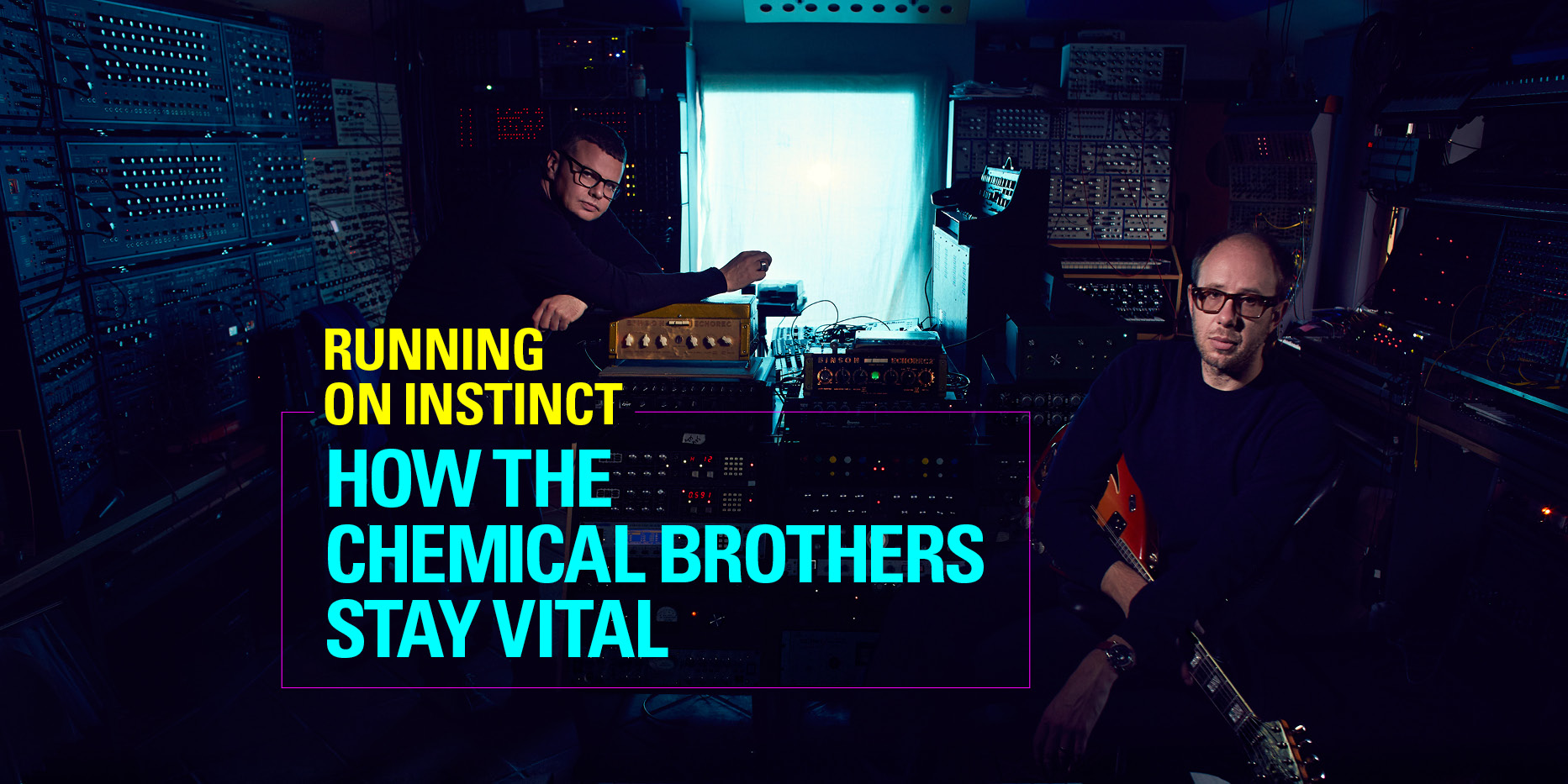

Tom Rowlands and Ed Simons. Photo by Hamish Brown.

Pitchfork: How is making music different for you guys now compared to when you were starting out 20 years ago?

Tom Rowlands: When we started making music, it's almost like we had no choice about what we made. There was only one thing that came out of me; I was trying to copy a Public Enemy record, but I wasn't up to it, so it came out like it did. But the more skillful you become, the more choices you have, like, "Oh, I could do it like this, and I could do it like that…" It's a curse, really.

For this record, it's almost like we were trying to unlearn our skills and do everything on a more instinctive level. A couple of years ago, we were listening to a lot of these old Ron Hardy edits, and it was all so strange and primal and wrong and raw—exactly what excites me about dance music. A lot of big, maximalized electronic music now is kind of easy to make, and we were trying to find a different sound.

Pitchfork: How did that decision play out as far as instrumentation and decisions on how the album would actually sound?

TR: We used a lot of the stuff that we used on our first couple of records: sequencers, Akai samplers, MPCs, old E-Mu drum machines. And there's a lot of samples of ourselves playing guitar or bass; creative sampling still really excites me. I love the idea of, like, a hi-hat from some old jazz record next to some sample you've made of dropping a piece of concrete into water next to the sound of playing a cymbal with a bow—all these weird things together. We're just really into making funny sounds and putting them into some kind of order that makes sense.

There's a lot of strange, half-broken old synthesizers all over the record, too. "Born in the Echoes" was made with antiquated technology, and that's another song that feels simple and clear, and when an interesting sound comes in, it's just the right sound. It feels like one of those strange records that you hear, and you're like, "What is that? Where is that from?"

Pitchfork: Another synthesizer track that stands out is "Taste of Honey", which sounds almost like ‘60s electronic pioneers Perrey and Kingsley with its buzzing bees, and then that guitar solo at the end. Was that a studio experiment that just—

TR: That went wrong.

Pitchfork: Or went right!

TR: It reminded us of things we put on some of our early records that weren't fully formed, ideas that took you on strange trips to some other place—I love it when that bee comes through my brain. There's obviously some humor in it. Not every song has to be the meaning of life.

Pitchfork: How did you decide upon the featured vocalists for the album?

TR: When we collaborate with people, it's always from a perspective of us being a fan of what they do, and them having some kind of unique voice or approach to making music as well as being open to experiment. I love the process of collaboration, where you have an idea and someone else has an idea that you'd never have imagined, and the music moves on from that.

Being in the studio with St. Vincent, you feel like you're in the presence of someone who is an artist, who can just conjure things up. She's amazing. And as far as track that we made with Beck, we'd been working on the music for a while, and it always felt like we needed something that really connects emotionally, so it was a joy for him to bring that to the record.

Pitchfork: You were pioneers of live electronic music. In the days before Ableton, was it difficult to take what you did in the studio and translate it to the stage?

TR: In 1993, we were DJing tiny parties in London, but when people asked us to DJ at big events, we'd be like, "Oh no, we're not proper DJs. We'll come and play live!" We would set up in the club with an MPC and some analog synthesizers and everything would get very sweaty and break. Now, the idea terrifies me, but it was a different time, really.

One of the first places we played live for a lot of people was in Orlando, in 1994. We were just amazed that someone knew who we were and got in touch and paid for a plane ticket to America to play. And then we turn up, and it's a massive, full-on rave. We had this track, "Chemical Beats", and we'd show up with an MPC and a Juno-106 and some distortion pedals and just make it up.

Pitchfork: Was there a sense of culture shock in those first trips to America, before you had any idea of what was happening in the States?

TR: Yeah. No one was asking us to come and play that kind of thing in England then. We'd turn up in the States and play records like "Song to the Siren" and people would know them. It was mind-blowing, really. We'd made this record in our bedroom, and suddenly we were in America, which for us was an exotic place to go—even though, I must admit, Orlando is maybe not the most exotic place in the world. But for us, at that time, we couldn't believe it! And then we'd go off to San Francisco and New York.

Someone the other day was saying they were surprised at the massive EDM-ification of American music, but we used to go there in 1994 and play these big raves that were all separated by scenes and miles. And now they're all being joined up.

Pitchfork: Even though Ed isn't touring with you now, you guys still DJ together, right?

TR: Yeah, we always DJ together, and it definitely feeds into our music and stops us from disconnecting. It makes you excited about making music, which I think is something that a lot of people in more traditional bands kind of lose that as they play live less. But in general we just like to play small DJ events.

Pitchfork: You started out in a world of intimate clubs, yet the music you make feels better suited to festivals. It's almost like the current festival format grew up around electronic artists like you, whose music is too big to be contained by a dance club.

TR: Well, I don't know. From our initial experience of dance music, it was this dual thing of being in small local nightclubs and then going to massive raves, where you'd have 20,000 people dancing to a Renegade Soundwave record. It's always seemed to us like dance music does work on that scale. People were amazed that Orbital could play a big stage at Glastonbury in 1994, and I was like, "of course!" because we had seen Orbital play in a massive field outside London to the same amount of people. It always felt like this music was made to be shared. I remember playing "Leave Home" in the basement of a pub in 1994, and you can play that same piece of music on a stage at Woodstock. That's what I like about music. You make it, and it goes off and becomes something else, or it doesn't. You don't really control what it means.