Beloved amateur video essayist Tony Zhou earned knowing nods across the internet when he observed in a 2014 video that “in the last four or five years, something’s happened: Filmmakers have started adopting a new formal convention, the on-screen text message.” At the time, shows like Sherlock and House of Cards were relatively new, and the way they depicted texting, shunning the zoom-in onto a phone screen in favor of overlaying words directly onto the picture, felt groundbreaking.

Five years later, on shows like Jane the Virgin and The Bold Type, this mode of on-screen texting has become ubiquitous: Television is full of shows where characters’ messages are transposed into bubbles and boxes on the screen. The conversation has moved beyond how to portray texts on screen because texts themselves have changed. They’re multimedia now. People aren’t just texting words to each other: They’re texting emojis; they’re sending screenshots; some weirdos are even trading voice memos. (They’re also doing so in group texts, Slacks, and DMs.) What’s more, people do all sorts of things on their phones beyond text: They Google, they tweet, they like Instagram posts. Smartphone use on TV is generally less likely to incorporate these behaviors, not that they’re particularly advanced; TV characters tend to be a few years behind the rest of us, tech-wise, and how to portray what’s happening on our screens remains an ongoing challenge for film and TV show–makers. That’s why it’s so surprising that amid this, a few shows have taken upon themselves to do something new, and in a way, a little radical: They’ve showed GIFs on screen.

This is where it gets confusing, so let’s clarify: Usually, moments from TV shows become GIFs. Witness this one of the Broad City girls using their middle fingers to move up the corners of their mouths after someone on the street yells at them to smile: Great TV moment begets great GIF. But that’s not what we’re talking about here. We’re not talking about what may, technically speaking, be the original TV GIF, the dancing baby from Ally McBeal. We’re talking about a TV show, in a display of its devotion to realistic storytelling, showing a GIF on screen, because the show seeks to portray that in real life, the way many of us live and talk to each other and experience the world is, well, with GIFs.

The GIF’s staying power in pop culture was not preordained. As a format, the GIF is almost 32 years old, which is, as Wired has put it, “ancient in web years”—strange, the magazine noted, because “the proliferation of animated GIFs is a relatively recent phenomenon.” The theory goes that while early web design trends of the nascent years of the internet moved beyond the GIF, the format stuck around in social online spaces like Reddit and web forums, and then the rise of smartphones allowed internet culture to flourish and people to start inserting GIFs all over the place. What might have been a passing fad persisted and continues to be an enduring mode of online communication.

So perhaps it’s not such a surprise that GIFs have made the trippy leap from a format mostly used to immortalize moments from media, like TV, to bits of visual texture in those very media. “In terms of GIFs being prevalent in TV shows, it just shows more and more how GIFs are becoming a standard form of communication,” said Ernestine Fu, the chairwoman of Gfycat, a service that provides users with tools for creating GIFs. It’s just logical that if TV shows seek to be realistic about how people communicate with each other, GIFs ought to be a consideration. “Memes, gifs, emoticons, all these things are just language,” said Matt Schimkowitz, a senior editor at Know Your Meme, the meme database.

Still, the idea of GIFs on TV does sort of feel like it could kick off a world-destroying paradox, doesn’t it? There’s a whoa factor to thinking about GIF use on any TV show—isn’t it weird that we make GIFs out of TV shows, so we could potentially have a GIF that contains a GIF of another GIF? “We’re at a point in popular culture where the history of the medium is being layered on top of each other,” said Anna McCarthy, a professor at New York University who has studied the animated GIF.

But let’s ignore that for now. The GIF’s slow infiltration of television has had a big year. Perhaps you noticed the GIFs in the first episode of Broad City’s fifth and last season, which aired earlier this year: The entire episode took the form of a string of social media “Stories,” à la Instagram, as if it were made up of footage that one of the show’s main characters, Ilana, shot on her own phone. These stories were peppered through with GIFs to make them look more like the Stories we all see every day in our own social media travels. For example, early in the episode, Ilana shows off her outfit, bragging about a pair of shoes she got on sale, and a small cartoon of some cash with flapping wings pops up in the picture. It’s a GIF! A few minutes after that, we get a still photo of the shoes (because on Instagram, sometimes Stories are photos, and other times they’re videos), with a graphic of an American flag waving next to the shoes: another GIF, this time a patriotic one. Later, Ilana injures herself and gets a wheelchair of some kind, and to add to the footage she’s taking of herself mugging for the camera with her new wheels, she adds some rotating 3D text that reads, “Hot Since ’94.” It’s a total GIF party.

What Broad City did may not have looked revolutionary, because it resembled the images we all see inside our phones all the time. But melding such ephemera into an entertaining, coherent narrative was no small feat. McCarthy praised Broad City’s GIF spectacle: “The whole narrative is told from a kind of first-person social media perspective, so you need GIFs for the verisimilitude of that,” she said. “It wouldn’t be social media if there weren’t GIFs.” Schimkowitz added: “Broad City is an example of a show that really understands the language it’s using. It knows how to use these things effectively and in a way that doesn’t feel like they’re speaking down to the people that are watching it. It doesn’t feel like it’s trying to exploit internet culture just to engage a young audience.”

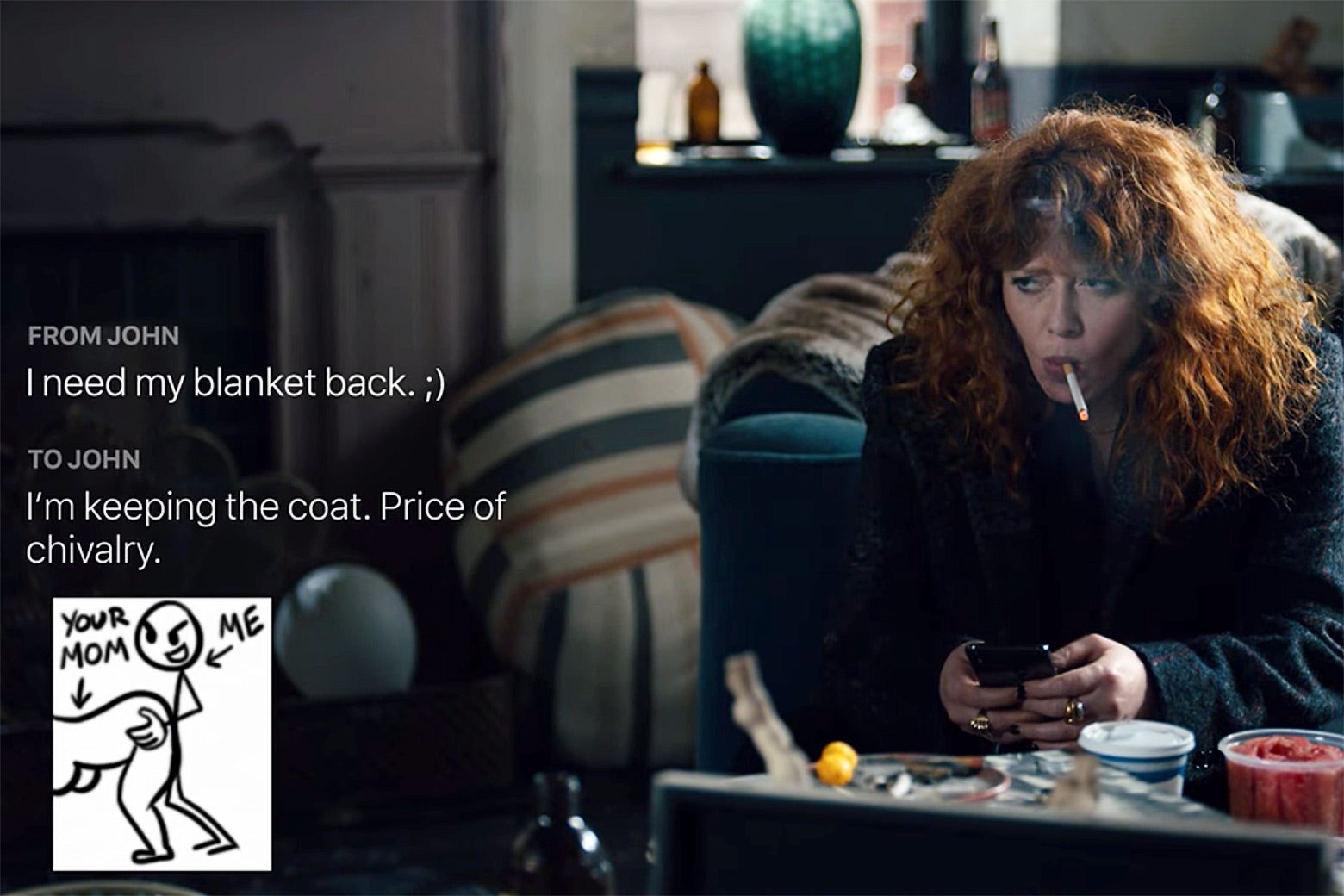

Broad City is far from alone in its embrace of the GIF. Also this year, in the third episode of Russian Doll’s first season, main character Nadia gets a text from her ex-boyfriend saying that he needs his coat back—he put it over her when she was sleeping. She responds that she’s not giving it back. “Price of chivalry,” she writes. And for good measure, she adds a GIF of a stick figure, labeled “me,” having sex from behind with a woman, labeled “your mom.” It’s a pretty revealing character moment, you have to admit.

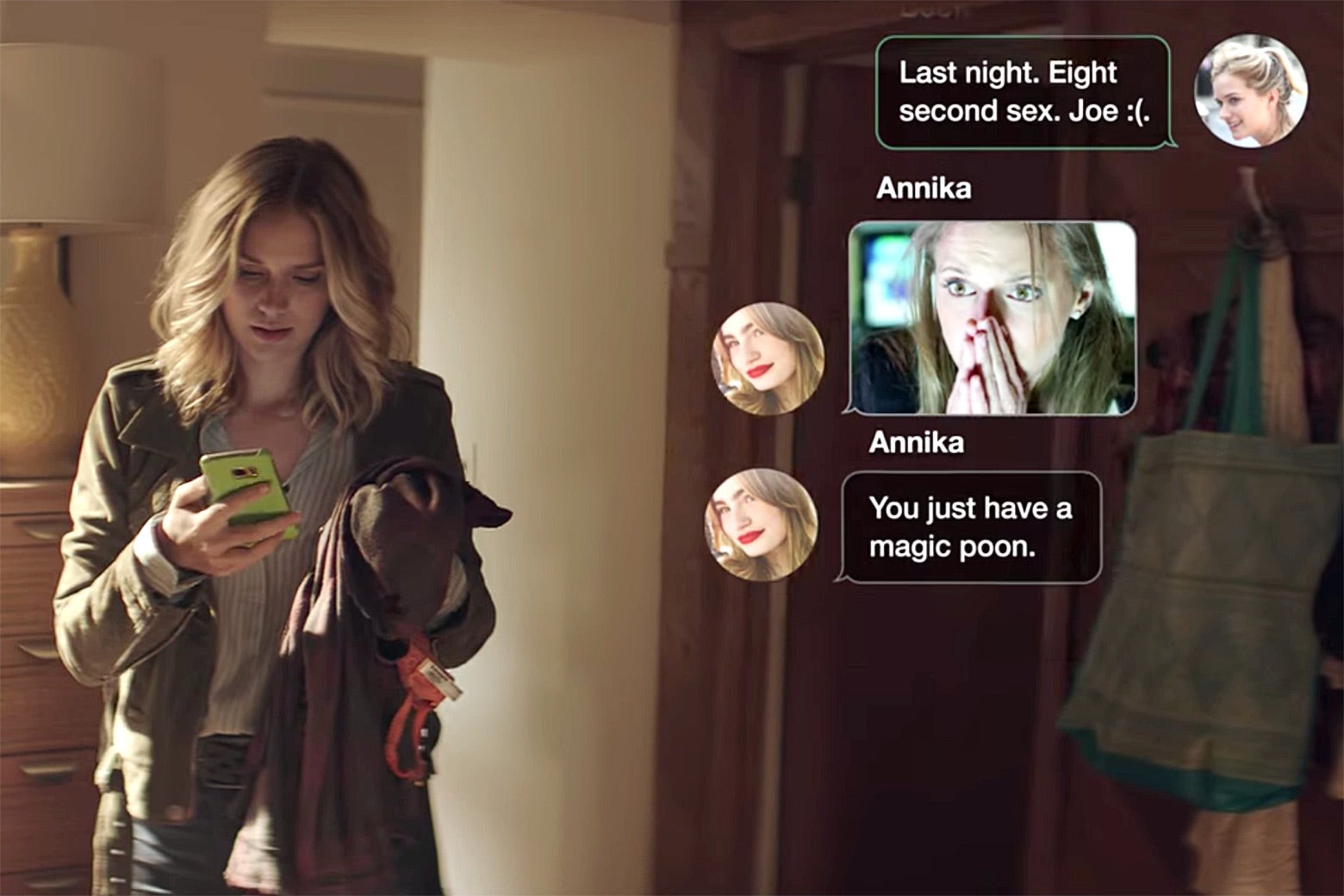

The on-screen text message exchange that Zhou originally highlighted seems to be the most popular context for showing a GIF on TV. It’s how it happened on Insecure, a GIF pioneer, having used one from the TV show Martin in a 2017 episode (Season 2’s “Hella LA”). It’s also the pretext for the GIFs that appear in You, the former Lifetime series that took Netflix by storm a few months ago. In a group text between female lead Beck and her best girlfriends, they respond to one of her texts with reaction GIFs, but notably, they aren’t recognizable reaction GIFs but generic ones seemingly created for the show: an unknown girl covering her mouth with her hands in surprise, another sitting in a theater and shielding her eyes. You and Russian Doll’s workarounds (animation and off-brand GIFs) show that one thing standing in the way of realistic technology on television and full GIF verisimilitude might be copyright law.

Then there was how The Simpsons handled a GIF earlier this year. The show also chose the text message route, inserting a GIF into an exchange between Homer and Lisa.

Homer backing into a bush is a classic GIF, one you’ve probably used or received, that translates to something like, “I’ll just pretend I wasn’t here.” It’s so classic, apparently, that Homer himself uses it: In a January episode of the show, the character texted it to his daughter Lisa. It’s the TV GIF I’ve encountered that most directly invites the paradox of endless GIF loops. “You could probably send your brain into a tailspin trying to figure out why that GIF would exist in the world of The Simpsons,” said Schimkowitz, of Know Your Meme.

This also speaks to how complicated it can be to reproduce culture. The Simpsons effectively reused and remixed its own joke, and You and Russian Doll approximated how people GIF, if not the exact materials with which they do it. When a show uses an existing, and well-known, GIF, is it depicting how real people communicate, or getting a laugh off of someone else’s material? “It’s a little bit tricky to navigate when you use a meme or a GIF,” Schimkowitz said. Referring to the moment when the movie Black Panther gave a shoutout to the internet by referencing the “What are those?” Vine, he went on, “Even the Black Panther thing, it was exciting for them to use ‘What are those?’ But that’s not Black Panther’s joke. That’s someone else’s joke.” When we layer all this media on top of each other, as McCarthy put it, things can get complicated.

That’s TV’s problem, though—for a company like Giphy, the GIF-discovery platform, the continued ascension of the format into mainstream culture is an unqualified win. Broad City had a preexisting relationship with Giphy before its foray into GIFs—the company has partnerships to live-GIF lots of TV shows on social media—but its producers gave the company a heads’ up about its plans for its season premiere, according to Stacy Rizzetta, the senior director of content development there. “We were really excited to hear that they wanted to specifically do an episode that revolved around social media, that revolved around GIFs.” As far as taking up the cause of promoting the use of more GIFs on TV, “It’s not necessarily something that we’re actively seeking,” Rizzetta said. No GIF lobby—for now. Still, “I definitely find myself thinking that GIFs should somehow be more a part” of what’s on television, she added. So one day soon, don’t be surprised if you see your favorite character side by side with a GIF on your TV screen. It’s not a gimmick; it’s the way we live now—dot gif.