“Muhammad Ali may be, outside of the Pope, the most beloved figure in the world. … He was willing to stand on his principles.” So said Dick Ebersol, a former NBC executive, recalling why he wanted Ali to light the torch at the 1996 Olympic games in Atlanta. That moment has become symbolic of the global reverence for Ali. Visibly ailing from Parkinson’s, Ali shook as he lit the torch, his determination to overcome adversity a heartwarming symbol of American greatness.

Such reminiscences of Ali in his later years represent an interesting revision of historical reality. When Ali announced to the world in 1964 that he was a Muslim, he was not only mocked but forced to sideline his boxing career. Far from a man of principle, an American patriot representing his nation on the world stage, he was derided as a “brainwashed” fool.

“Brainwashing” is a much-disputed concept in contemporary psychology, which has found that it’s impossible to scientifically replicate conditions under which a person’s mind and personality can be forcibly changed. The term nevertheless continues to circulate widely in popular culture and some academic studies. Anti-vaxxers allege that everyone lining up for the COVID-19 vaccination “jab” has been brainwashed by pharmaceutical companies and “big government.” Their critics assert that anti-vaxxers are the real brainwashing victims. News reports, pop psychology analyses, and survivors’ accounts describe “brainwashing” within secretive and coercive organizations, from the multilevel marketing sex club NXIVM to the Scientology community. It’s a term so commonly used today to discredit a controversial religion or an opposing political viewpoint that we have lost sight of how important Muhammad Ali was to its popularization in the early 1960s.

Cassius Clay, the name given to Ali by his parents, returned from the 1960 Olympics in Rome as a boastful star. Just 18 years old, he proudly displayed his gold medal when he mugged for the cameras. Riding around his hometown of Louisville in a pink Cadillac, he teased his opponents with nicknames and rhymes. In the ring, he was a serious competitor. He won nearly all of his fights on the heavyweight boxing circuit.

With a seemingly innate flair for courting publicity, Clay nevertheless tried to keep his religious life private. Cassius and his younger brother, Rudy, had been raised in a Baptist household, but by 1962 they regularly attended Nation of Islam rallies and visited its temples. Initially oblivious to the shift, journalists eventually took note. They pestered Cassius with questions about whether he was a “Black Muslim,” the term for members of the Nation of Islam adopted by editors of both historically white- and Black-owned newspapers but rejected by members of the Nation. Cassius refused to answer.

The first allegation of “brainwashing” came from Clay’s father. In early February 1964, about two weeks before Cassius Clay was scheduled to face Sonny Liston in the heavyweight title fight in Miami, a reporter tracked down Cassius Clay Sr., a 51-year-old sign painter, at his home in Louisville. Clay Sr. described his son as a weak-willed victim of the Nation of Islam’s information campaigns. Leaders of the Nation, he said, had been indoctrinating his son for years, “hammering him and brainwashing him.” Later portrayed by biographers as a tough and even cruel parent, Clay Sr. insulted his son’s intelligence: “[The Nation’s leaders] deal only with the ignorant colored people.” Clay Sr. laid most of the blame at the feet of Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, accusing him of practicing nefarious forms of mind control.

The idea that Cassius Clay had been brainwashed by leaders of the Nation of Islam reflected a growing fear about mind control as a particularly frightening aspect of communists’ strategies in the Cold War. A 1950 study of coercive Chinese methods of indoctrination had introduced the word brainwash into English vernacular. When about two dozen American prisoners of war refused repatriation at the end of the U.S. military action in Korea in 1953, social scientists and others looked for ways to explain why these American men would choose communism over American democracy. “Brainwashing” became the default explanation. It connoted mental coercion, employed by communist oppressors to force their ideas on the people whose freedoms they had stolen.

Fears of brainwashing pulsed through Cold War America. The CIA secretly studied whether its agents could use brainwashing to their own advantage, testing the effects of psychedelic drugs such as LSD as a means of mind control. Brainwashing seemed to explain mass conformity and even the popularity of political movements. It became part of the zeitgeist, providing the turning point in the plot of The Manchurian Candidate, the popular 1959 novel about U.S. soldiers who returned home to the United States unaware that their minds remained under the thrall of the Chinese communists who “brainwashed” them during captivity. The film version of The Manchurian Candidate played on screens in Kentucky; perhaps Cassius Clay Sr. saw it, read about it, or heard it discussed among friends and clients.

Cassius Clay Sr.’s allegation that his son had been “brainwashed” was the first time that the concept was used publicly to discredit a religious convert. Reporters ran after Cassius Clay Jr. to get his response to his father’s insulting remarks. Cornered in Miami in early February 1964, he refused to take the bait: “I don’t care what my father said. I’m not interested and I’m not talking,” he told a reporter. Headline writers forged ahead; “Brainwashing,” blazed the Washington Post.

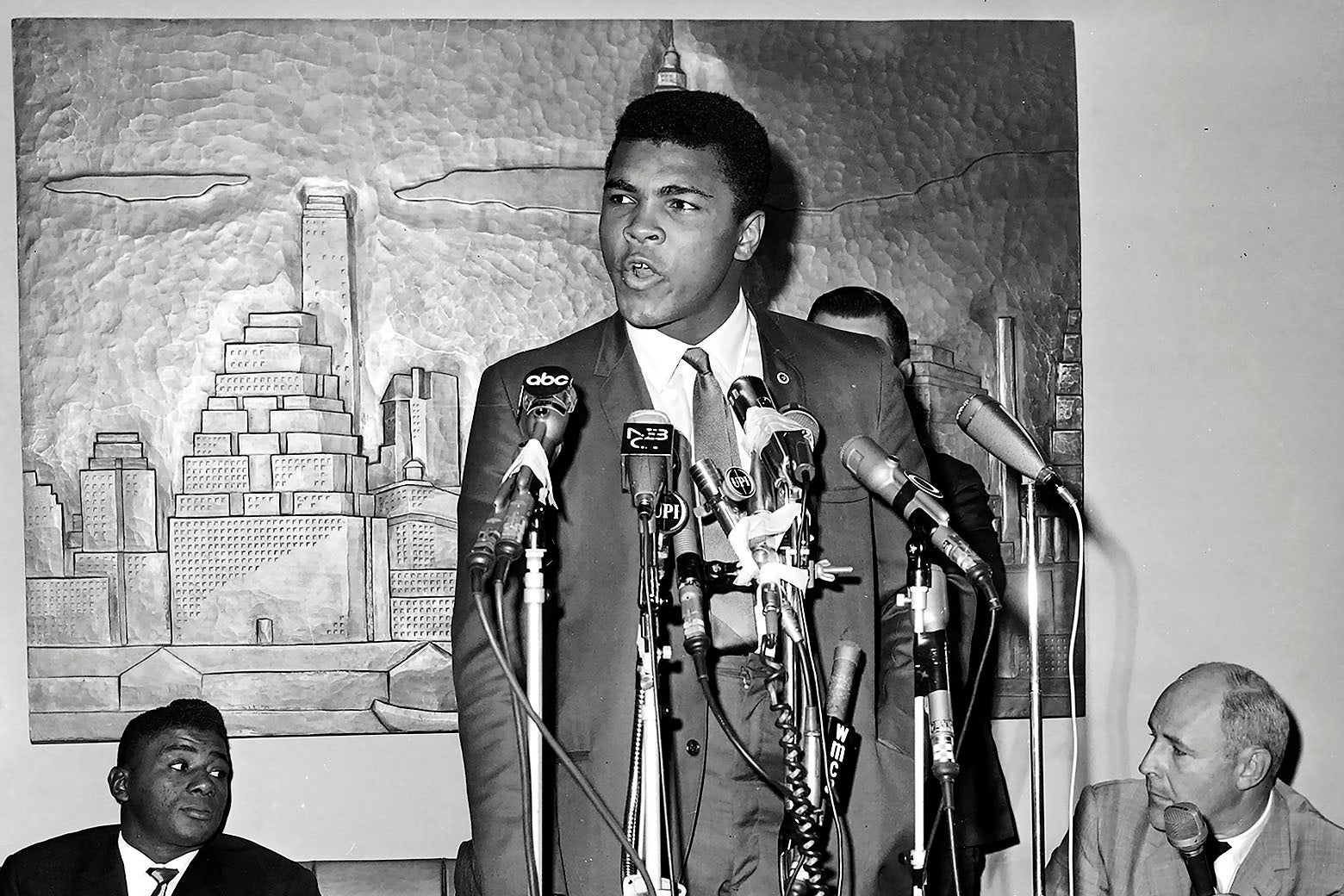

The boxer saved his first public announcement that he was a member of the Nation of Islam until after he had defeated Sonny Liston in late February 1964 to become the world heavyweight boxing champion. The morning after the fight, he put the rumors to rest by affirming that Islam was his religion. Over the next several days and weeks, Cassius Clay continued to explain why he loved Islam, a religion of peace, and why he agreed with the Nation’s philosophy of racial separation. Elijah Muhammad gave him the name Muhammad Ali. The boxer became, next to the Nation’s fiery orator Malcolm X, the most famous member of the Nation.

Muhammad Ali was learning from Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad that white people had been brainwashing Black people for millennia, and that the Nation offered their only hope of intellectual and spiritual autonomy. In a 1967 speech at Howard University, Ali explained, “See, we have been brainwashed. Everything good and of authority was made white. We look at Jesus, we see a white with blond hair and blue eyes. … Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in Black Africa, he’s white!” Writer James Baldwin similarly recalled Elijah Muhammad’s comments about the importance of resisting the “brainwash” of lies about American history that white people told themselves. Black people, Baldwin explained, coped by “dismiss[ing] white people as the slightly mad victims of their own brainwashing.”

“Brainwashing” connotes the loss of a person’s ability to make a free choice, but that freedom was exactly what Muhammad Ali claimed when he defended his new faith. “I know where I’m going and I know the truth and I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want,” he told reporters in Miami. He paid a steep price for his religious freedom. In the spring of 1964, the World Boxing Association threatened to strip him of his title because of his conversion to a religion its leaders found offensive. Boxing fans booed announcers who called him Muhammad Ali instead of Cassius Clay. Ali’s principled refusal of the draft in 1966 ultimately led to the revocation of his boxing license and his title, depriving him of his ability to fight when he was at his physical prime.

Widespread fears about the growth of “cults” in the 1970s put “brainwashing” front and center once again, gesturing to it as a way to understand why some people converted to faiths that others found unappealing or dangerous. Psychologists and other social scientists thoroughly debunked the notion of brainwashing, however, in the 1980s, finding instead that individuals made their own decisions about what they believed, and that ideological systems all engaged in varying degrees of social control.

As he aged, Muhammad Ali became a symbol of the very qualities denied to him in the 1960s. Denigrated as a traitor to his nation when he refused to be inducted into the U.S. Army, Ali lit the Olympic torch in 1996 as a living emblem of patriotism. The faith that once discredited him now proved his devotion to peace. And if the idea of “brainwashing” erased his intellectual or spiritual agency in the 1960s, later in life he signified the freedom to choose a religion according to conscience. During a telethon to raise money for first responders after the al-Qaida attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, actor Will Smith introduced Ali as “one of the greatest heroes of our time, and he is a Muslim.” President George W. Bush awarded him the Medal of Freedom.

This historical footnote about Muhammad Ali reveals the vacuousness of using “brainwashing” to discredit an opposing viewpoint. Whatever its rhetorical power, “brainwashing” is too crude a concept to encompass the complex reasons why people come to believe what they believe and which principles they stand for. When someone else’s beliefs are so contrary to our own—so steeped in white supremacy, for example, or supportive of Black separatism—“brainwashing” implies that this person was coerced into their opinions. The harsher reality is that ideas we find repellant are often quite appealing to others. And as Ali’s life reminds us, “brainwashing” can all too easily serve to discredit the deeply held beliefs of people whose race, faith, or national identities challenge the status quo.