This Fourth of July, in parades across the country, you’ll likely see Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty together, smiling, waving, maybe holding hands. Their jaunty appearance as America’s Odd Couple is as predictable as the parades’ antique cars and marching bands. In fact, the idea of them as a twosome dates back more than a century to when Uncle Sam and (a fairly fierce looking) Lady Liberty first teamed up to sell war bonds and boost enlistment in World War I, and later World War II.

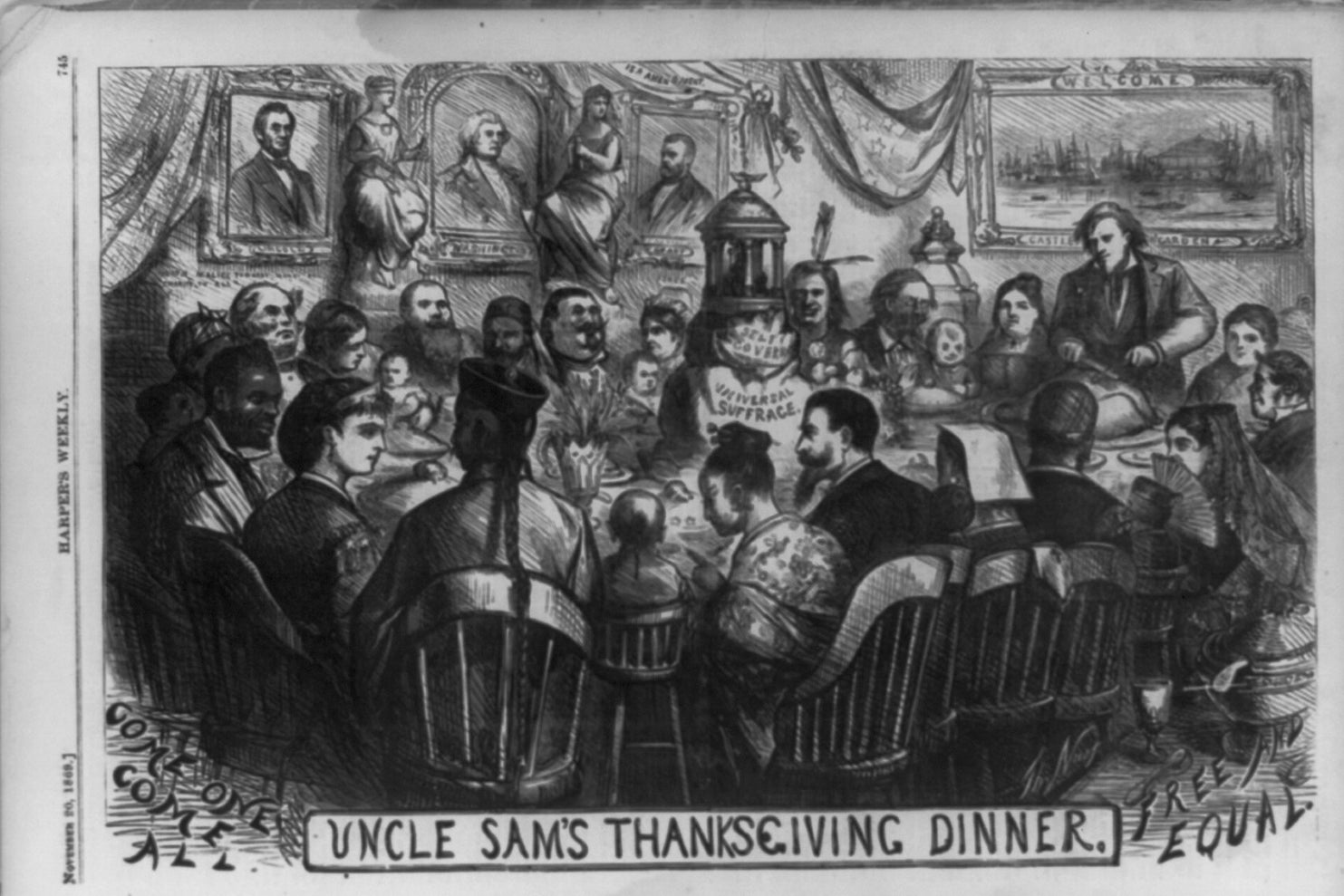

But don’t believe their cheery handholding. Though Uncle Sam was officially recognized as a national symbol in 1950, and Liberty as a national monument in 1924, the truth is that they have always been on opposite sides of the most contentious issues in America, beginning even before the Statue of Liberty’s inauguration in 1886. The job of personified national symbols is to promote a unified citizenry, a task cartoonist Thomas Nast attempted to accomplish in his very first drawing of Uncle Sam in 1869, a sentimental multicultural fantasy he called “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner.” Instead, Sam and Liberty routinely mirror our divisions. The United States is the only country that has two such diametrically opposed personified national symbols. In 2022, this looks like a warning.

Both Sam and Liberty are old—she’ll turn 136 this year, and he’s 210—and most people in the US don’t know their full histories, but they each have a coherent biography, initiated by editorial cartoonists like Nast and carried forward by their successors, as well as advertisers, illustrators and photographers. Though there are outlier characterizations of both Sam and Liberty, media has generally depicted their incompatiblity in our country’s areas of deepest conflict—immigration, race and religion.

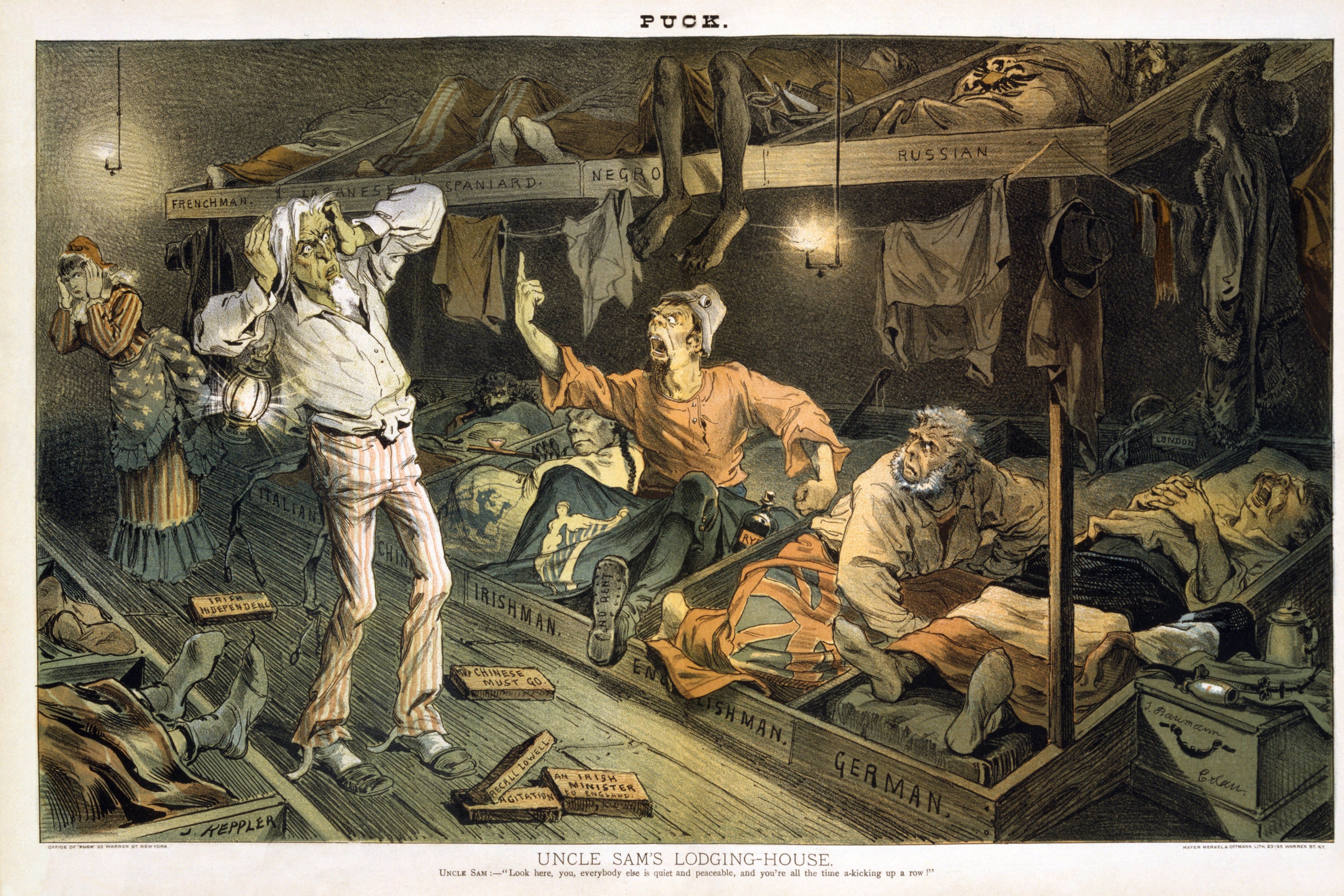

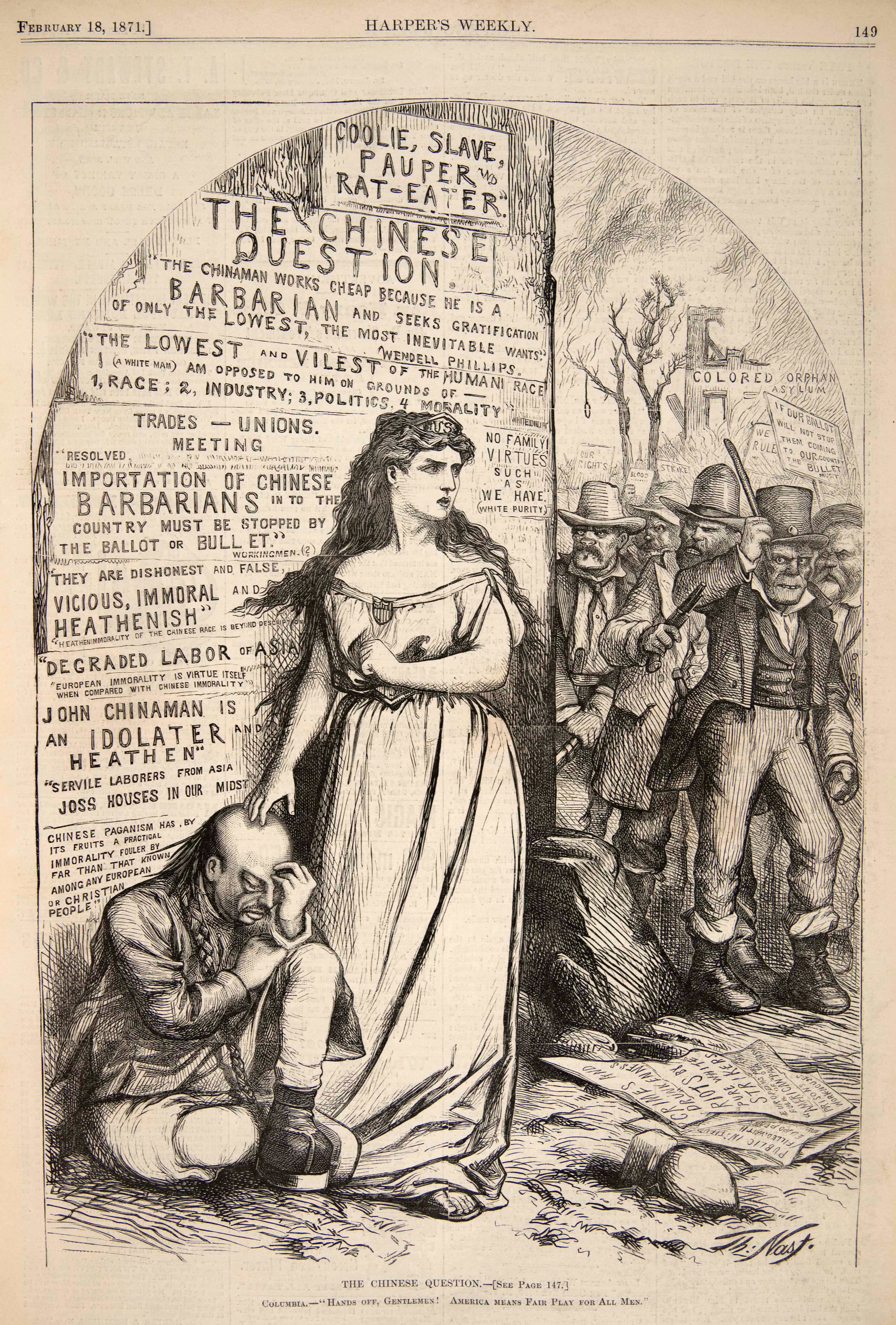

Sam—said to be named after Sam Wilson, a merchant from Troy, New York who supplied the troops with meat during the War of 1812—has long been represented as a militaristic religious bigot, a nativist, a racist, and an imperialist. In the period between the end of the Civil War and the start of World War I, the consensus among the most well-known editorial cartoonists was that Sam was a nativist who opposed entry for all immigrants who were not Northern Europeans—namely, the Chinese, Japanese, Italians and other southern European immigrants, Eastern European Jews, particularly those fleeing the pogroms of Russia, and Roman Catholics, especially the Irish.

Sam is our second male national symbol. For the first half of the 19th century, he was overshadowed by Brother Jonathan, a carryover from the original colonies. Some say Jonathan’s namesake was Connecticut Gov. John Trumbull, who supported the Revolution and was supposedly called “Brother Jonathan” by George Washington. Alternately, “Brother Jonathan” was a derogatory name for Puritans dating back to the English Civil War (1642-1651), which was later extended to colonial Puritans by the British. As a figure, Brother Jonathan was an enterprising, if crafty, businessman. During the 1840s, however he became increasingly associated with the Know-Nothing Party, made up of native-born Protestants who felt threatened by the waves of German and Irish immigrants arriving. These immigrants’ growing presence ignited nativist bigotry in general, and antipathy to Roman Catholics in particular, as you can see in a political cartoon by Nathaniel Currier (of Currier and Ives) that also shows how much Brother Jonathan sometimes resembled Uncle Sam.

By the late 1850s, because he had been claimed by the Know-Nothings for their own, Brother Jonathan was no longer a viable national symbol. As Jonathan gradually receded, Sam became more prominent, mostly acting as his brother’s surrogate in opposing immigration, starting with the Chinese.

Meanwhile, after the Civil War, Lady Liberty was first conceived of as a celebratory symbol of slavery’s end, by Frenchman Édouard De Laboulaye, an expert on the US Constitution and an abolitionist. Some years later, Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi was commissioned to design her statue. By 1886, with Jim Crow laws in place, Liberty’s original commitments were less popular. Instead, she was introduced to the American public as a gift from France and a symbol of Franco-American friendship. What remained of the original conception by the time she was installed in New York harbor was a broken shackle at her feet—a symbol of emancipation, mostly hidden by her gown. By 1901, Liberty was little more than a green elephant, a failed lighthouse in disrepair.

The Statue of Liberty had her own female predecessor in Columbia, said to have first been personified as a symbol of America at the start of the American Revolution by the Black American poet Phillis Wheatley, in “To His Excellency, General Washington.” Sometimes Columbia is depicted as a maternal figure with long flowing hair, as protective of immigrants as Sam was abusive, and explicitly sympathetic to Black Americans during the Civil War. Alternately, Columbia is depicted as a symbol of liberty, identifiable by her red, white and blue garments and her headgear, known as a Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty worn by freed slaves in the Roman Empire and carried forward to the French Revolution. Either way, Columbia as a symbol lasted into the 20th century, but faded away as the Statue of Liberty gained symbolic power.

In the 20th century, both Sam and Liberty acquired language. For Sam, it was the famous “I Want You” World War I recruitment poster. As for Liberty, she got a voice of her own in 1903 when Georgina Schuyler, a politically progressive descendant of Alexander Hamilton, had a bronze plaque hung in Liberty’s pedestal inscribed with “The New Colossus,” the now-famous sonnet written by her late friend, Emma Lazarus. This was a massive rebranding, countering Sam’s nativism, and naming her “The Mother of Exiles,” speaking up to defend “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

It took Liberty a few decades to fully consolidate her new identity as a protector of immigrants, initially reinforced via illustration or photograph. However, according to historian Roger A. Fischer, Liberty’s new identity solidified fairly quickly. Rarely was she treated irreverently and rarely (but not never) positioned on the wrong side of an issue like immigration. In 1924, Columbia Pictures presented Columbia as its logo. In 1926, she was provided with a torch in her raised right hand, explicitly merging her with Lady Liberty, and establishing her once and for all as a pop culture icon.

As we become more polarized, Liberty and Sam—our archetypal mother and father—do, too. These days, Sam has been explicitly embraced by 21st century Know-Nothings, most notably the Proud Boys, five of whose leaders have now been indicted for “seditious conspiracy” in relationship to the events of January 6. Other right-wing fans of Uncle Sam’s include state and local Republicans, for instance, Arizona Republicans who recently used his iconic “I Want You” poster —with Donald Trump’s face inserted—to recruit poll watchers.

Happily, whether by design or zeitgeist, the evidence seems to be that within the federal government, Uncle Sam is currently under-employed. Since the end of World War II, he hasn’t been given much of anything to do in the way of official business. The last postage stamp to show his face was issued in 1998. Since then, all we’ve seen of him is his hat. In 2017, in a promising impulse, the government issued a postage stamp, “Uncle Sam’s Hat,” that attempted to merge the symbol of Sam with the idea of ethnic diversity. Sam’s hat also appears at the website, Sam.gov, where those doing business with the federal government can register.

As a representation of most of us, Lady Liberty has fared much better, in recent years, than Uncle Sam. As the symbol for a racially diverse nation, Liberty has the advantage of being just slightly ambiguous—not identifiable by her ethnicity, or time or place of birth. Even the circulating rumors about her origins enhance her multicultural popularity, one being that the original model for the Statue was Black. (A 2000 report neither confirms nor denies this assertion about the model, while finding no existing evidence that Bartholdi intended the Statue to be a black woman.) Liberty’s explicit or implicit association with certain political groups—like NARAL or New York State (which used her image in PSAs advocating vaccines and mask wearing)—will taint her as a symbol in some parts of the country, but the values she’s associated with—not only the right to abortion and the use of Covid vaccines and masking, but also gun control—have wider public support than those of Uncle Sam. The death of George Floyd prompted a few dozen editorial cartoonists to connect his dying words—“I can’t breathe”—to Liberty, most keeping her in character—maternal and protective.

National symbols aren’t something we can formally retire; they’re deep in the culture, and can only fade away, like Brother Jonathan or Columbia, as people’s values change. But this Fourth of July, if Sam and Liberty march by, hand-in-hand, at my parade, I know who I’m rooting for. Hey hey. Ho ho. Uncle Sam has got to go.