Nearly five years ago, on a muggy August night, I stepped outside and smoked my last cigarette. I’d just gotten off the phone with my Nana, who reminded me that my grandfather, a former smoker, died of lung cancer. My Nana isn’t a somber woman, not usually, but that night it was on her spirit. She solemnly asked me what I was going to do. And I, not usually a dutiful granddaughter, pivoted from my rebellious ways and obliged.

It wasn’t a bad choice to make. In the lead-up to the night I smoked my last Marlboro menthol, I had been considering dropping the habit anyway. While I thought smoking made me more attentive, I was always tired and fatigued. I couldn’t get up a flight of stairs, or down the block, without being winded. And, perhaps most disturbingly, I would hack up a dark, cigarette ash–colored phlegm each morning.

Yet, I still smoked half a pack each day.

The fumes from a cigarette take the same route through your body as oxygen. Smoke travels down your throat and into your lungs. The blood vessels housed there absorb it rather quickly, and the smoke’s byproduct is pumped to your heart before being directed to your brain.

About 15 to 20 seconds after taking a puff, you start to feel the effects of nicotine.

“You’re getting a high level of nicotine to the brain, you’re getting it quickly, which reinforces behavior, and you’re also able to titrate the dose,” explained Neal Benowitz, an emeritus medical professor at the University of California, San Francisco and expert on smoking’s biological consequences. “If you get too much … you take a longer time until the next puff. Because of high levels, you overcome tolerance that would be present if you were using lowered levels. We know in general, smoking a drug is a highly addictive way of using it.”

My decision to start smoking menthols wasn’t a conscious one. They were the type of cigarette I saw smoked the most by the people around me, but I did deliberately choose to keep smoking them after I’d tried nonmentholated cigarettes. In the other option, the nasty taste of cigarette smoke was evident, and the smoke seemed thicker and harsher. Taking a pull from a nonmentholated cigarette required more lung power. It was like inhaling smog.

On April 29, the Food and Drug Administration announced that it plans to propose product standards that would ban cigarettes with added menthol, which have been disproportionately and insidiously marketed in Black communities. An earlier federal ban on flavor additives, adopted in 2009, prevented tobacco companies from producing cherry, vanilla, clove, and other sweet-flavored cigarettes. But menthol remained legal.

From its inception, the tobacco industry sought ways to make its products more palatable. One New York state health department report from 1888 says that sugar, licorice, molasses, and glycerin were added to smoking and chewing tobacco in hopes of improving the taste. These additives and flavorings, according to several researchers and physicians who spoke with Slate, are what make cigarettes more enjoyable and thus a harder habit to break.

Menthol is the “ultimate candy flavor,” said Phillip Gardiner, a public health researcher and activist. “It helps the poison go down easier.

“The number one killer of Black folks is tobacco-related diseases,” he continued. “The main vector of that is menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars.”

There are more than 7,000 chemicals in cigarette smoke. Some of them cause cell damage and chronic inflammation, which can lead to lung damage and heart problems. The resulting carbon monoxide levels in a smoker’s blood reduces oxygen delivery to the body. Smoking also increases the risk for atherosclerosis and blood clotting, and prevents the blood vessels from dilating normally. Smoking predisposes people to diabetes and can lead to adverse effects on cholesterol. It can also cause heart enigmas, which can be fatal in some scenarios.

Smoking can cause premature heart disease, sudden death, stroke; lung, kidney, bladder, esophageal, liver cancer, and leukemia, to name a few; and chronic obstructive lung disease. For pregnant people, there’s an increased risk of infections, especially in the lungs, premature birth, stillbirth, and infant sudden death. (Increases in lung cancer correlated with an uptick in smoking were observed as far back as the 1880s, said Suzaynn Schick, an associate professor of medicine at UCSF.)

While menthol doesn’t have a direct effect on nicotine levels, it does make cigarette smoke easier to inhale by masking its harshness. It also stimulates cold receptors, acts as an anesthetic, increases salivation, allows for deeper inhalation, slows the metabolism of nicotine, and increases how much nicotine is absorbed through the tissues that line the mouth.

Despite smoking fewer cigarettes per day and attempting to quit more frequently, Black smokers are more likely to die from tobacco-related diseases and tend to have higher levels of cotinine, a metabolite formed after nicotine enters the body, denoting a recent exposure to cigarette smoke, in their systems.

The mortality disparity is not rooted in any inborn biological differences. It’s likely due to a number of social factors—including quality of health care received, late diagnoses, apathetic health care providers, medical racism, and differential smoking behaviors. (One example, Schick explained, would be holding smoke longer because you’re getting by on fewer cigarettes.)

A federal ban on menthols might spur current smokers into successfully quitting. More than 85 percent of Black people who smoke opt for menthols, and one study found that 44.5 percent of Black people who smoke menthols would try to quit if the flavor additive were banned. Generally, the desire to quit was higher among Black respondents in several other studies. But Black smokers have a harder time stopping smoking, which is likely due to limited access to smoke cessation programs, fewer no-smoking mandates in public places, high community rates of smoking, higher stress levels, and the plethora of advertisements in Black communities. There’s some research that suggests menthols are also just harder to quit due to the physical and psychological effects provided by the flavoring.

“There’s this trope of people smoking to curb stress,” said Lincoln Mondy, who created Black Lives/Black Lungs, a short film looking at the tobacco industry’s role in the Black neighborhoods.

“What we don’t talk about enough is just how much trauma and how much stress our communities are going through and how we need holistic health,” he said. “We need proactive public health strategies, but it’s so, so clear that, at the same time as our communities—specifically in lower-income, Black, and Latinx communities—are going through so much … they’re looking for a bit of relief.”

This is where the tobacco industry comes in. In the industry’s mid-20th-century heyday, companies handed out free cigarettes in Black communities. Even now, menthols are cheaper in Black communities.

“When you add all of this up, plus the predatory marketing,” said Gardiner, “no wonder African Americans die disproportionately to tobacco-related diseases.”

By the 1950s, the tobacco industry had so deftly infiltrated American life that not smoking was pretty weird. In the later part of that decade, industry giants started looking into fostering underdeveloped markets, which kicked off an extensive, concerted effort to get Black people to use menthol cigarettes. In the early 1960s, Brown & Williamson, a tobacco company that later merged with R.J. Reynolds, held a series of focus groups that discovered Black smokers were more attracted to television advertising than their white counterparts.

So they dumped significant portions of their advertising budgets into TV ads.

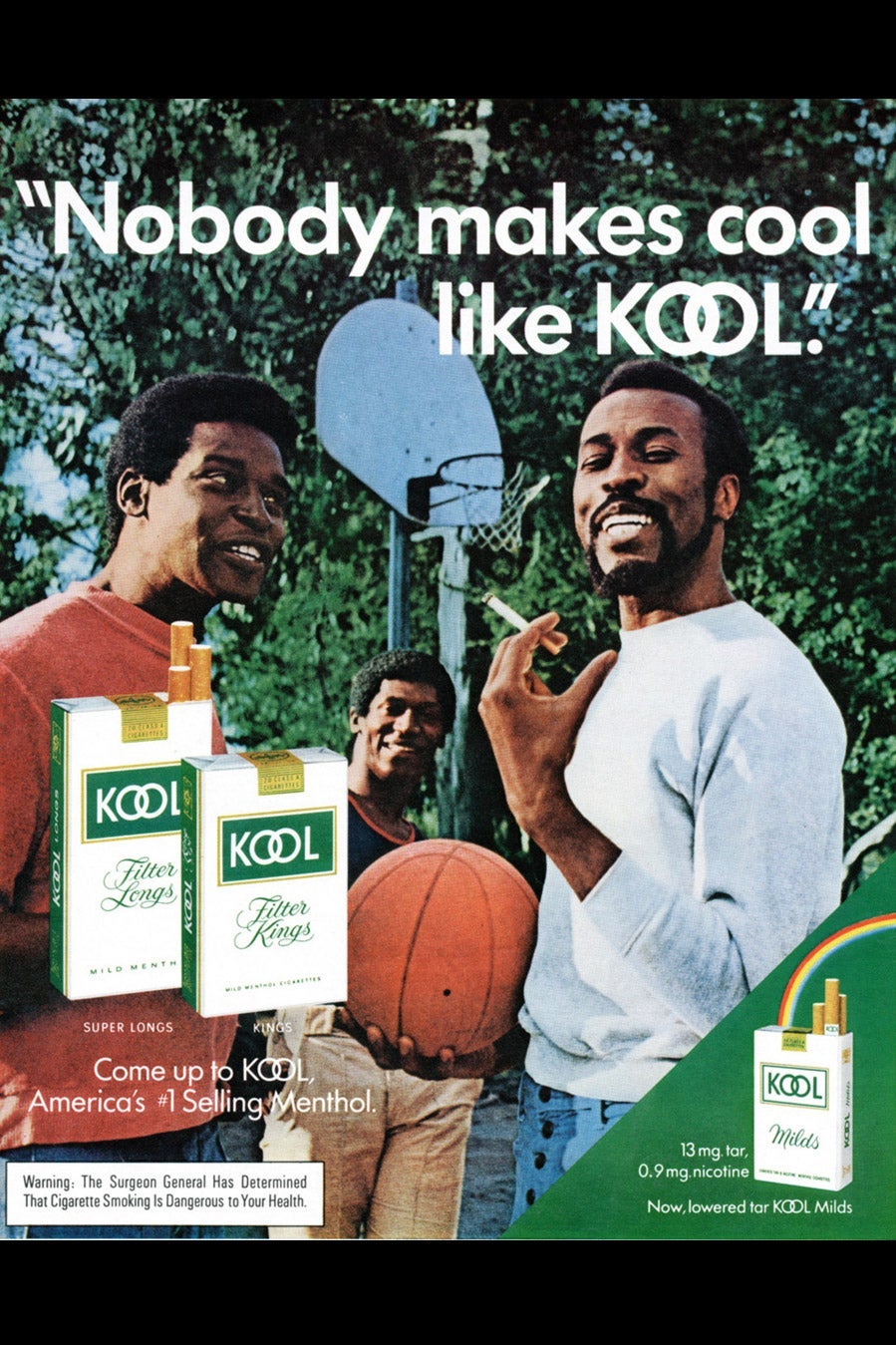

“They began to run commercials in the 1960s with Black athletes, particularly Elston Howard of the New York Yankees, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, all selling these products,” said Gardiner, who wrote the most comprehensive study on the tobacco industry’s advertising efforts in Black communities. “This is the midst of the civil rights movement going on. I mean, the March on Washington was in 1963. The bombing of the church in Birmingham was in 1963. Here we have, in 1963, Elston Howard selling cigarettes on national television.”

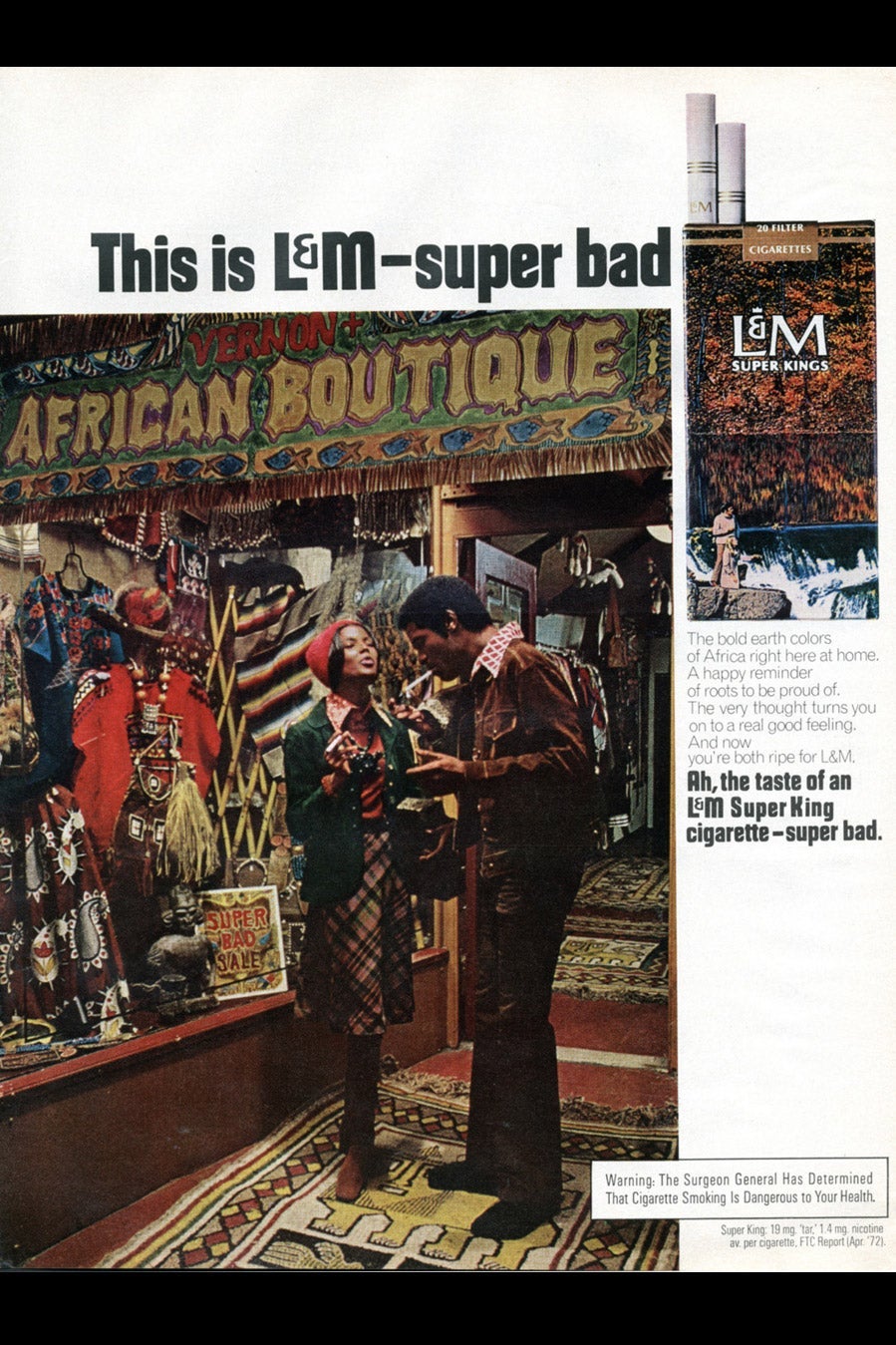

In one tobacco advertisement shown to me by Robert Jackler, a physician and expert on tobacco marketing, the now-defunct Tobacco Institute ran a “remember the man, remember the dream” ad aligning itself with Martin Luther King Jr. There are other ads, mostly from magazines like Ebony and Jet, that employed Black models who were lighter-skinned doppelgangers for famous Black actors and musicians.

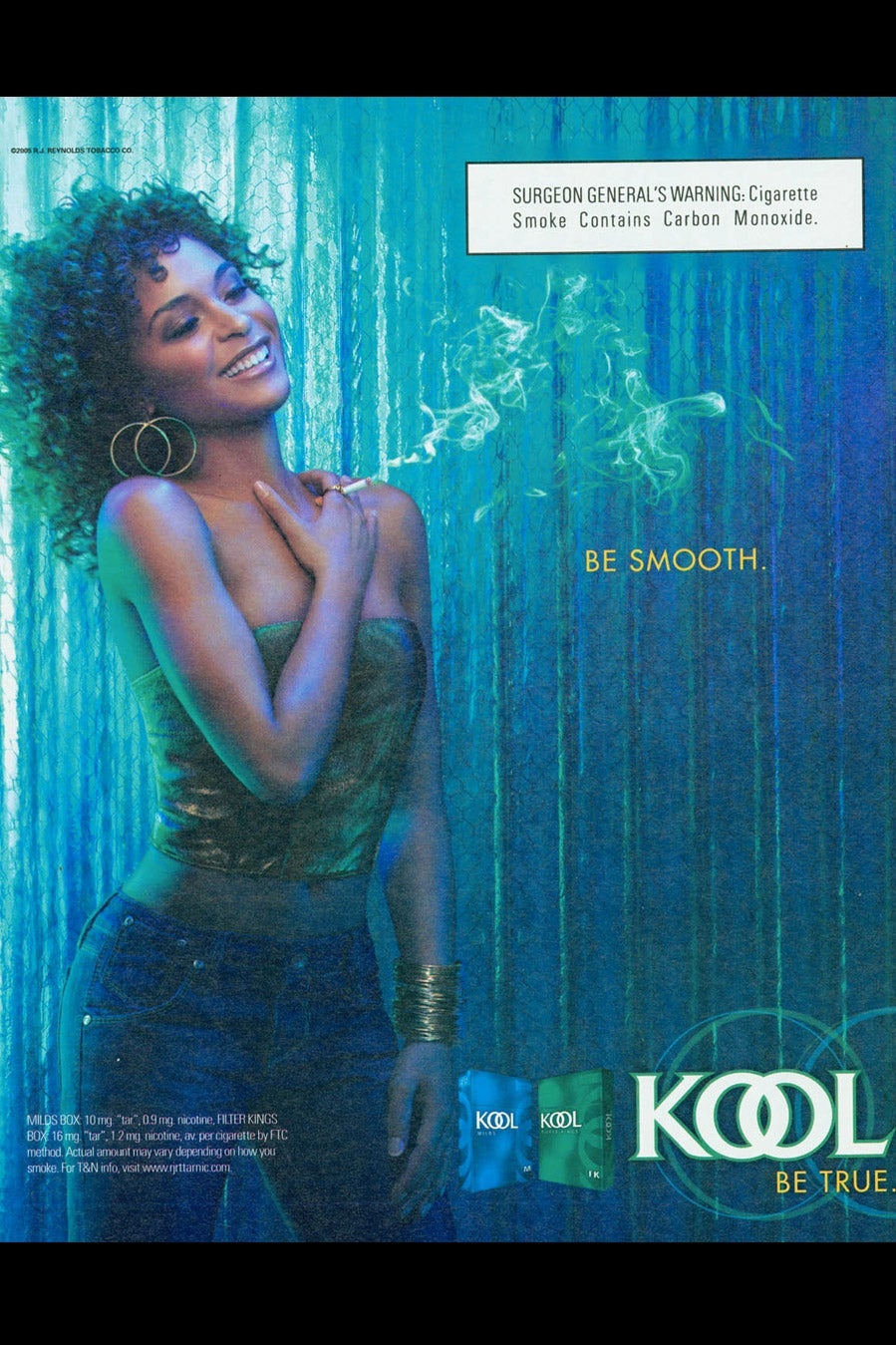

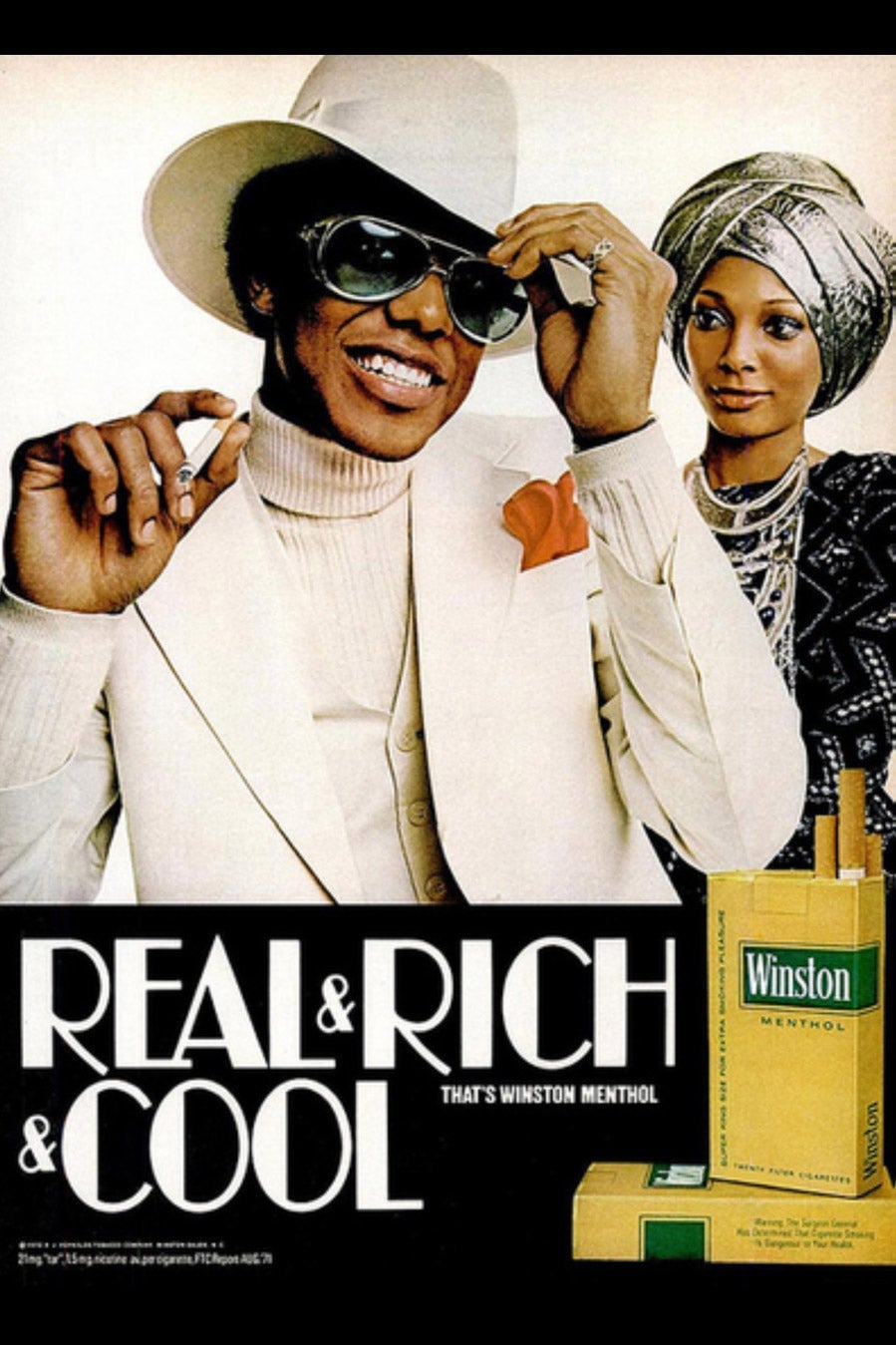

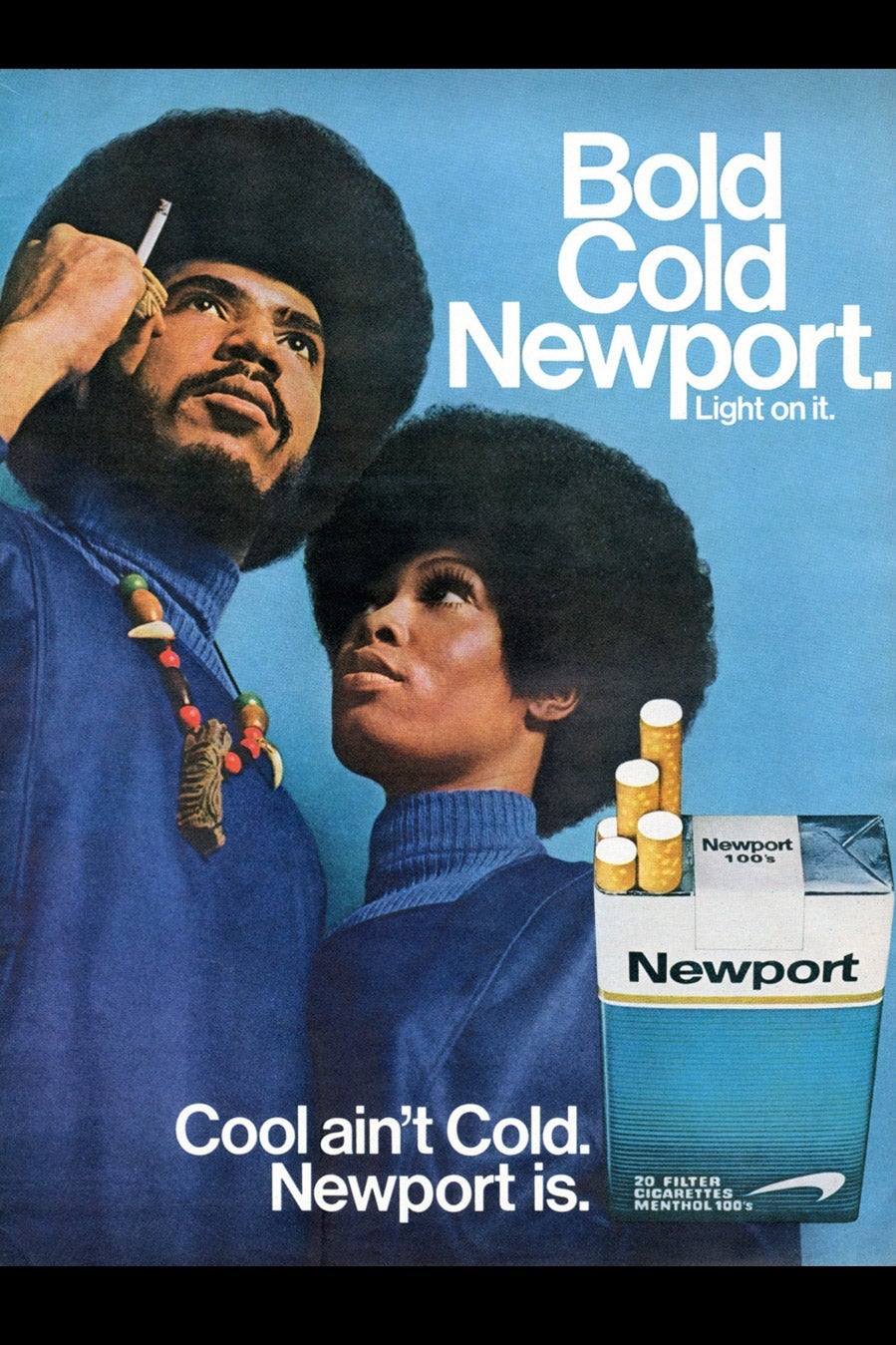

The majority of the advertisements employ aspirational marketing, said Jackler, who has collected almost 60,000 tobacco advertisements. Their energy implies that smoking will make you part of the crowd and that you can have a lifestyle that’s better than your current condition. For teenagers, this works because they want to be like the cool, twentysomething models seen in the advertisements. For young Black people, the idea was that menthols were “fresh and modern,” according to Gardiner’s research, and maybe even were healthier than nonmentholated cigarettes.

Tobacco advertisements emulated the shifting moods of Black culture over time. In the 1970s, companies ran ads showcasing Black models, standing dignified and sporting large Afros—echoing the Blaxploitation era and the personal style of prominent Black political figures. (One Newport ad in particular reminded me of the Black Panthers.) According to industry surveys cited in Gardiner’s research, people who smoked Kool cigarettes were perceived by their Black peers as brave, daring, tough, and ambitious. Some sloganing even mimicked popular songs of the time.

“These same qualities were the ethos of the mass African American liberation movement that was sweeping away and dismantling the main props of segregation and demanding fair housing, equal job and education opportunities, and an end to police brutality,” wrote Gardiner in his paper.

As the ads inched into more recent decades, companies pivoted from the single-race format to showing Black models alongside white ones. In the ’90s, the ads portray cigarette smoking as trendy, sexy, and exclusive, with photos resembling stills from Sex and the City or any other show you can’t watch on basic cable. Nowadays, tobacco companies are following society’s descent into wellness culture, boasting “plant-based cigarettes” even though tobacco is a literal plant.

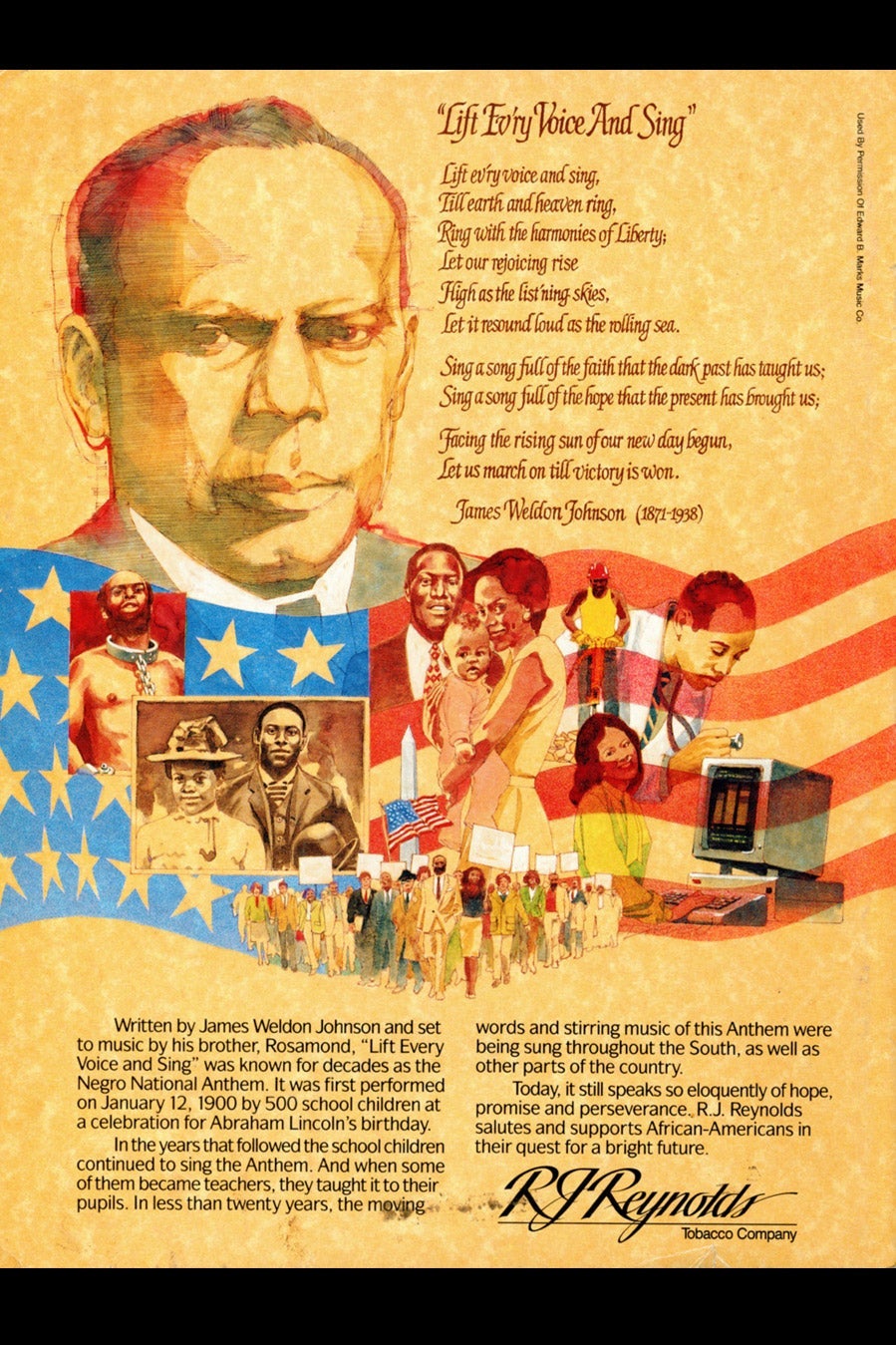

Tobacco companies also poured money into, and built relationships with, Black institutions. It was an insidious way to draw these industries closer and reduce the chances that they would raise any qualms about human health.

This history complicates the otherwise understandable expressions of concern that a ban on mentholated cigarettes could lead to police targeting individual smokers. A letter to the Biden administration, the Congressional Black Caucus, and other offices from the ACLU, Drug Policy Alliance, and other civil rights organizations warns that a ban could “lead to unconstitutional policing” and “trigger criminal penalties.” Al Sharpton, who has accepted money from the tobacco industry, has spoken out against the ban as well.

But it’s true there are already harsh penalties imposed upon people who sell and carry illegal tobacco products. And it’s not beneath the police to use unauthorized cigarette sales as a reason to instigate an unnecessary and potentially deadly interaction with a Black person. While the FDA has said that individuals will not be targeted under a potential ban, because the focus would be on the manufacturers, history invites skepticism.

Before the 2009 ban on additives became law, the Congressional Black Caucus was split on whether menthol should be included. At the time, the tobacco industry was one of the organization’s biggest donors, and Philip Morris threw its weight behind the bill as long as it didn’t include menthols. As it becomes more socially unacceptable to smoke, and as public health crackdowns ensue, Big Tobacco is funding anti-smoking groups and rebranding itself. Some industry giants, after decades of targeting Black people with their products, are attempting to make themselves look as though they’re aware of systemic racism—recently, the tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds used Eric Garner’s death at the hands of a New York police officer to denounce a proposed ban on menthols in the city.

There are 65 menthol bans of some sort in place around the United States currently, according to Gardiner’s estimate.

“The ban will not give police any more relationship with people who have a menthol cigarette than not,” said Gardiner. “Not one person has been arrested for a menthol cigarette possession because it isn’t in the laws at the local level or at the state level. This is not about individual possession.

“In fact, let’s take it a step further—there should be decriminalization of all commercial tobacco products, period,” he continued. “It’s about restricting the production, manufacture, the wholesaling, and retailing [of menthol cigarettes]. It has nothing to do with possession.”

And if anyone is worried about a black market, Gardiner says, look at the manufacturers. “In essence, where the black market starts is in Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia. That’s where the manufacturers are,” he said. “So how do they get from the manufacturer who has been told you can’t do this anymore to the underground market? You better look at the manufacturers.”

I still crave nicotine a few times a month, and I found working on this story to be quite triggering. I caught myself ruminating on what it would take for me to go buy a pack of smokes and if I could prevent myself from becoming “A Smoker” should I take another pull.

Benowitz told me that this is because the psychological aspect of what habitual smoking does to the human body is as powerful as the immediate physiological effects of the smoke.

When someone smokes thousands of times, their brain generates new brain circuits that function similarly to memory circuits. Animal studies have shown that those circuits remain months, or even years, later, which is why people are at risk of relapse years after they’ve quit. (Although, Benowitz said, the highest risk of relapse is within the first year.)

“Nicotine works because it mimics the effects of acetylcholine, which is the body’s natural and most prevalent neurotransmitter that conducts information from one cell to the next,” he said.

Acetylcholine works with nearly every organ in the body, which means nicotine could have effects on every organ in the body. In the brain, nicotine works mostly to release other neurotransmitters—like dopamine (pleasure), norepinephrine (arousal and appetite suppression), glutamate (learning and memory), endogenous opiates, and serotonin (mood modulation). And when an addiction is linked to something else that provokes enjoyment—like a certain flavor or a cup of coffee—it’s more reinforcing.

If the rule-making process for a menthol ban were to go smoothly, it could take years before being enacted. The tobacco industry could also sue and disrupt the process. In the interim, Gardiner and Mondy both emphasized the need to invest in cessation programming that is well-funded, accessible, culturally appropriate, and meets people where they are. Cigarettes are profoundly addictive and a ban, while a worthy start, won’t be enough on its own.

“All the work that we’ve been doing at the local level and state levels to get bans in place must continue, because the federal government is going to take years to deal with this,” said Gardiner. “During that time, many lives are going to be lost. We should be about saving Black lives.”