TO

WILLIAM TENNANT GAIRDNER,

M.D.,LL.D.,F.R.S.,

In admiration of his noble character,

Philosophic teaching, wide culture, and

many labours devoted with exemplary fidelity to

the interpretation of nature and the service of man.

This book

is respectfully dedicated

by The Author.

FROM A PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

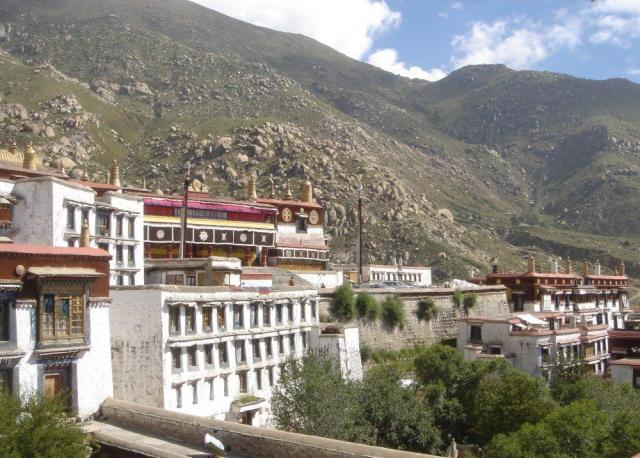

Little positive was known about the Buddhism of Tibet- that far off vast isolated towering tableland and “Forbidden land” on the roof of the World in Middle Asia, separated by the icy walls of the Himalayas from the Indian plains, the homeland of the Buddha and Buddhism before the publication of this book in 1895.

It was written under uniquely favourable circumstances for penetrating for the first time the frigid reserve and jealously guarded mysteries of the Tibetan Buddhist priests or “Lāmas.” This Tibetan term “Lāma” means in Tibetan literally “the Superior or Exalted One” and significantly it is the literal Tibetan translation of “Arya” or “Aryan” or Sumerian Ar ”exalted or noble “); but used in an ecclesiastical Buddhistic, and not in a racial sense.

PREFACE.

NO apology is needed for the production at the present time of a work on the Buddhism of Tibet, or “Lāmaism ” as it has been called, after its priests. Notwithstanding the increased attention which in recent years has been directed to Buddhism by the speculations of Schopenhauer and Hartmann, and the widely felt desire for fuller information as to the conditions and sources of Eastern religion, there exists no European book giving much insight into the jealously guarded religion of Tibet, where Buddhism wreathed in romance has now its chief stronghold. The only treatise on the subject in English, is Emil Schlagintweit’s Buddhism in Tibet

[ Leipzig and London, 1863 That there is no lack of miscellaneous literature on Tibet and Lāmaism may be seen from the bibliographical list in the appendix ; but it is all of a fragmentary and often conflicting character]

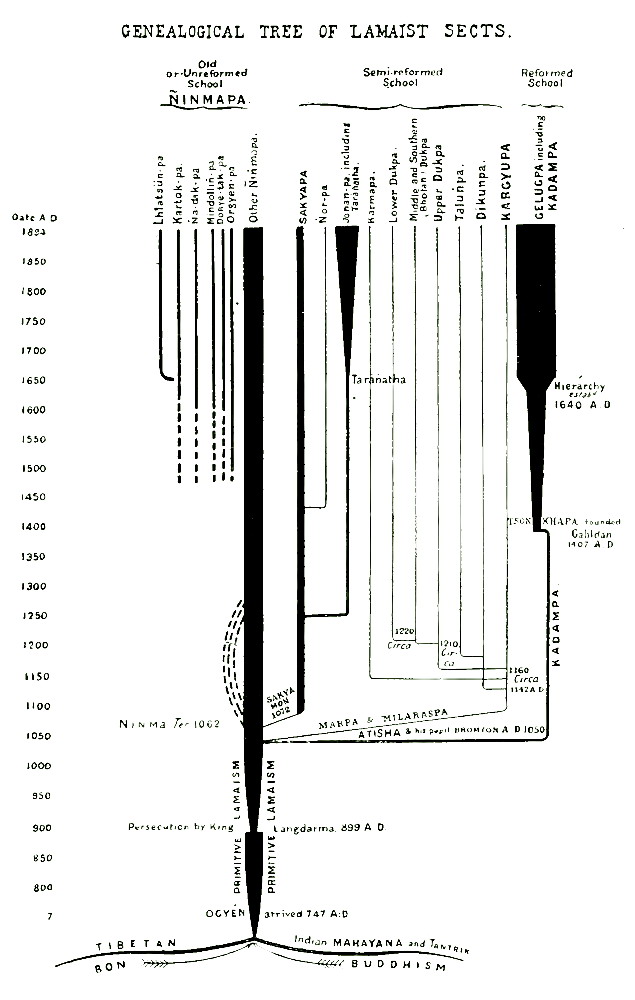

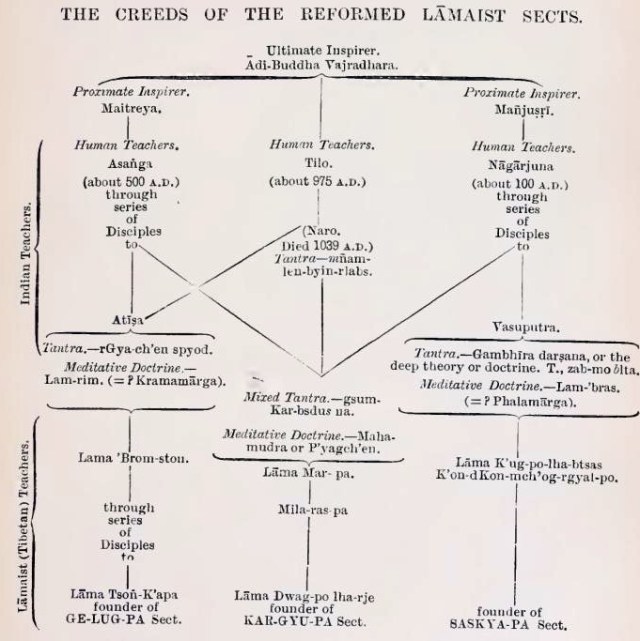

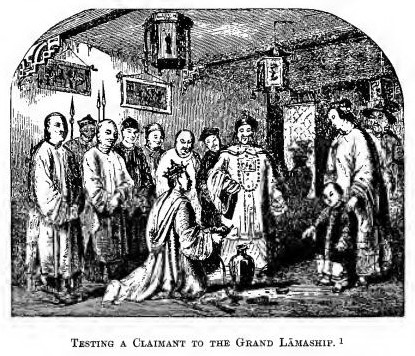

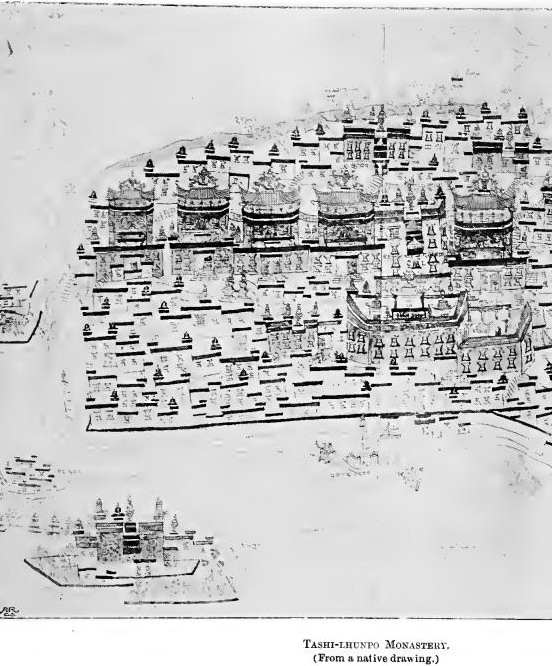

published over thirty years ago, and now out of print. A work which, however admirable with respect to the time of its appearance, was admittedly fragmentary, as its author had never been in contact with Tibetans. And the only other European book on Lāmaism, excepting Giorgi’s curious compilation of last century, is Koppen’s “Die Lāmaische Hierarchie und Kirche” published thirty-five years ago, and also a compilation and out of print. Since the publication of these two works much new information has been gained, though scattered through more or less inaccessible Russian, German, French, and Asiatic journals. And this, combined with the existing opportunities for a closer study of Tibet and its customs, renders a fuller and more systematic work now possible. Some reference seems needed to my special facilities for undertaking this task. In addition to having personally studied “southern Buddhism” in Burma and Ceylon ; and “northern Buddhism” in Sikkim, Bhutan and Japan; and exploring Indian Buddhism in its remains in ” the Buddhist Holy Land,” and the ethnology of Tibet and its border tribes in Sikkim, Assam, and upper Burma ; and being one of the few Europeans who have entered the territory of the Grand Lāma, I have spent several years in studying the actualities of Lāmaism as explained by its priests, at points much nearer Lhāsa than any utilized for such a purpose, and where I could feel the pulse of the sacred city itself beating in the large communities of its natives, many of whom had left Lhāsa only ten or twelve days previously. On commencing my inquiry I found it necessary to learn the language, which is peculiarly difficult, and known to few Europeans. And afterwards, realizing the rigid secrecy maintained by the Lāmas in regard to their seemingly chaotic rites and symbolism, I felt compelled to purchase a Lāmaist temple with its fittings ; and prevailed on the officiating priests to explain to me in full detail the symbolism and the rites as they proceeded. Perceiving how much I was interested, the Lāmas were so obliging as to interpret in my favor a prophetic account which exists in their scriptures regarding a Buddhist incarnation in the West. They convinced themselves that I was a reflex of the Western Buddha, Amitabha, and thus they overcame their conscientious scruples, and imparted information freely. With the knowledge thus gained, I visited other temples and monasteries critically, amplifying my information, and engaging a small staff of Lāmas in the work of copying manuscripts, and searching for texts bearing upon my researches. Enjoying in these ways special facilities for penetrating the reserve of Tibetan ritual, and obtaining direct from Lhāsa and Tashi-lhunpo most of the objects and explanatory material needed, I have elicited much information on Lāmaist theory and practice which is altogether new. The present work, while embodying much original research, brings to a focus most of the information on Lāmaism scattered through former publications. And bearing in mind the increasing number of general readers interested in old world ethics, custom and myth, and in the ceaseless effort of the human heart in its insatiable craving for absolute truth ; as well as the more serious students of Lāmaism amongst orientalists, travelers, missionaries and others, I have endeavored to give a clear insight into the structure, prominent features and cults of this system, and have relegated to smaller type and footnotes the more technical details and references required by specialists. The special characteristics of the book are its detailed accounts of the external facts and curious symbolism of Buddhism, and its analyses of the internal movements leading to Lāmaism and its sects and cults. It provides material culled from hoary Tibetan tradition and explained to me by Lāmas for elucidating many obscure points in primitive Indian Buddhism and its later symbolism. Thus a clue is supplied to several disputed doctrinal points of fundamental importance, as for example the formula of the Causal Nexus. And it interprets much of the interesting Mahayana and Tantrik developments in the later Indian Buddhism of Magadha. It attempts to disentangle the early history of Lāmaism from the chaotic growth of fable which has invested it. With this view the nebulous Tibetan ” history ” so-called of the earlier periods has been somewhat critically examined in the light afforded by some scholarly Lāmas and contemporary history ; and all fictitious chronicles, such as the Mani-kah-‘bum, hitherto treated usually as historical, are rejected’ as authoritative for events which happened a thousand years before they were written and for a time when writing was admittedly unknown in Tibet. If, after rejecting these manifestly fictitious “histories” and whatever is supernatural, the residue cannot be accepted as altogether trustworthy history, it at least affords a fairly probable historical basis, which seems consistent and in harmony with known facts and unwritten tradition. It will be seen that I consider the founder of Lāmaism to be Padma-sambhava — a person to whom previous writers are wont to refer in too incidental a manner. Indeed, some careful writers omit all mention of his name, although he is considered by the Lāmas of all sects to be the founder of their order, and by the majority of them to be greater and more deserving of worship than Buddha himself. Most of the chief internal movements of Lāmaism are now for the first time presented in an intelligible and systematic form. Thus, for example, my account of its sects may be compared with that given by Schlagintweit, 1 to which nothing practically had been added. [1 Op.cit., 72.] As Lāmaism lives mainly by the senses and spends its strength in sacerdotal functions, it is particularly rich in ritual. Special prominence, therefore, has been given to its ceremonial, all the more so as ritual preserves many interesting vestiges of archaic times. My special facility for acquiring such information has enabled me to supply details of the principal rites, mystic and other, most of which were previously undescribed. Many of these exhibit in combination ancient Indian and pre-Buddhist Tibetan cults. The higher ritual, as already known, invites comparison with much in the Roman Church ; and the fuller details now afforded facilitate this comparison and contrast. But the bulk of the Lāmaist cults comprise much deep-rooted devil-worship and sorcery, which I describe with some fullness. For Lāmaism is only thinly and imperfectly varnished over with Buddhist symbolism, beneath which the sinister growth of poly-demonist superstition darkly appears. The religious plays and festivals are also described. And a chapter is added on popular and domestic Lāmaism to show the actual working of the religion in every-day life as a system of ethical belief and practice.

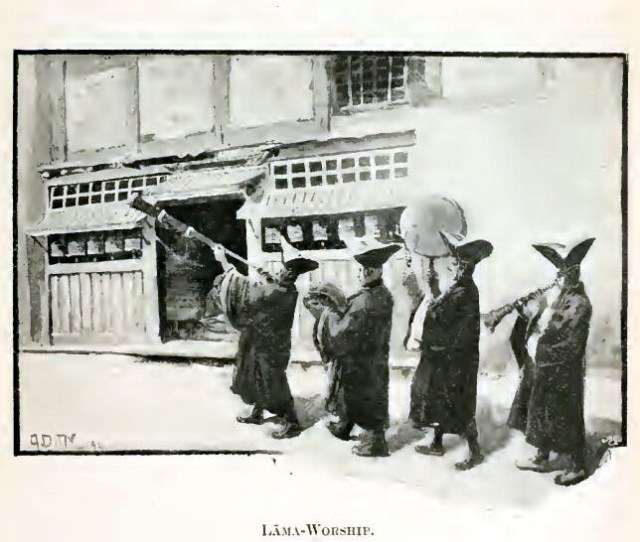

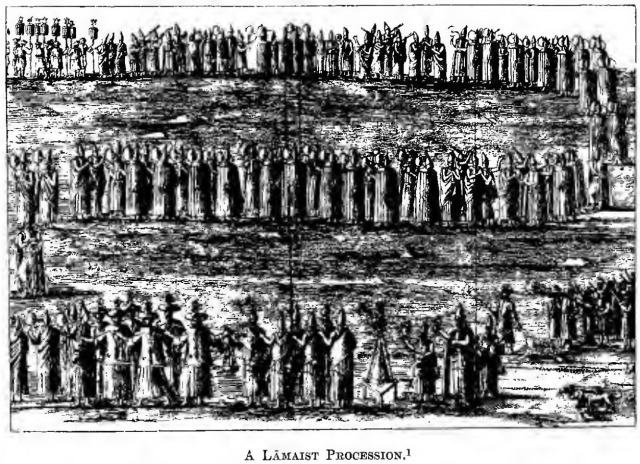

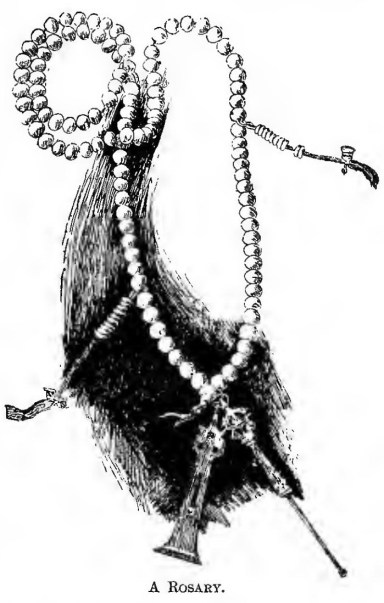

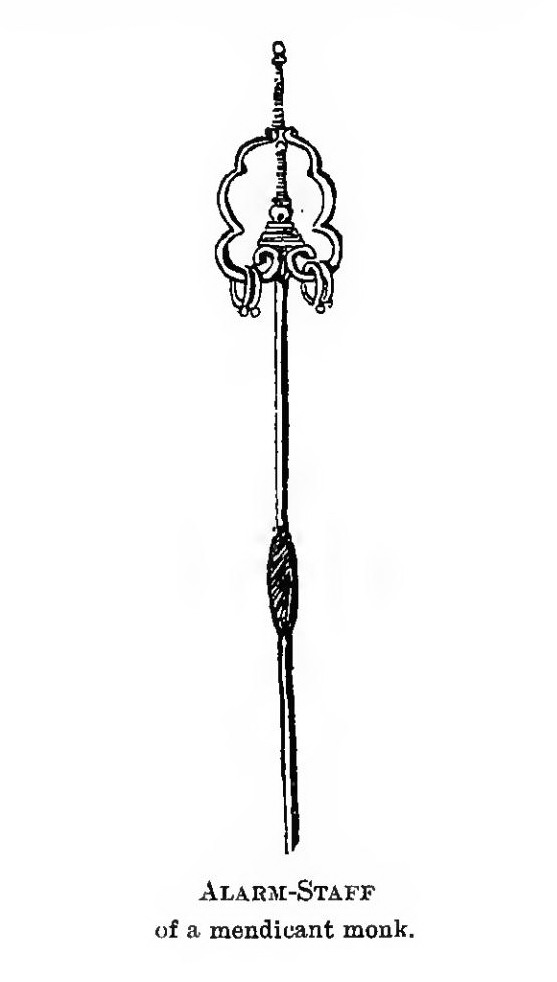

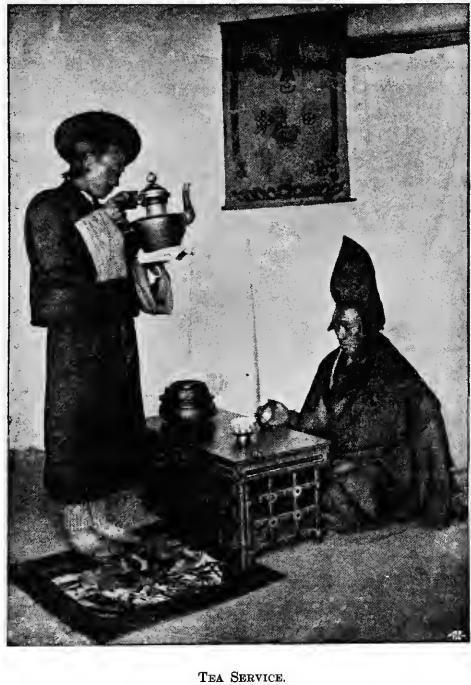

3 A few of the drawings are by Mr. A. D. McCormick from photographs, or original objects ; and some have been taken from Giorgi, Hue, Pander, and others.

A full index has been provided, also a chronological table and bibliography . I have to acknowledge the special aid afforded me by the learned Tibetan Lāma, Ladma Chho Phel ; by that venerable scholar the Mongolian Lāma She-rab Gya-ts’o; by the Nin-ma Lāma, Ur-gyan Gya-ts’o, head of the Yang-gang monastery of Sikkim and a noted explorer of Tibet; by Tun-yig Wang-dan and Mr. Dor-je Ts’e-ring; by S’ad-sgra S’ab-pe, one of the Tibetan governors of Lhāsa, who supplied some useful information, and a few manuscripts; and by Mr. A.W. Paul, C.I.E., when pursuing my researches in Sikkim. And I am deeply indebted to the kind courtesy of Professor C.Bendall for much special assi stance and advice ; and also generally to my friend Dr. Islay Muirhead. Of previous writers to whose books I am specially under obligation, foremost must be mentioned C’soma Korosi, the enthusiastic Hungarian scholar and pioneer of Tibetan studies, who first rendered the Lāmaist stores of information accessible to Europeans. 1 Though to Brian Boughton Hodgson, the father of modern critical study of Buddhist doctrine, belongs the credit of discovering 2 the Indian nature of the bulk of the Lāmaist literature and of procuring the material for the detailed analyses by Csoma and Burnouf. My indebtedness to Koppen and Schlagfntweil has already been mentioned.

1. Alexander Csoma of Koros, in the Transylvanian circle of Hungary, like most of the subsequent writers on Lāmaism, studied that system in Ladak. After publishing his Dictionary , Grammar, and Analysis, he proceeded to Darjiling in the hope of penetrating thence to Tibet, but died at Darjiling on the 11th April, 1842, a few days after arrival there, where his tomb now bears a suitable monument, erected by the Government of India. For details of his life and labours, see his biography by Dr. Duka. 2.Asiatic Researches, XVI 1828.

Jaeschke’s great dictionary is a mine of information on technical and doctrinal definitions. The works of Giorgi, Vasiliev, Schiefner, Foucaux, Rockhill, Eitel, and Pander, have also proved most helpful. The Narrative of Travels in Tibet by Babu Saratcandra Das, and his translations from the vernacular literature, have afforded some useful details. The Indian Survey reports and Markham’s Tibet have been of service ; and the systematic treatises of Professors Rhys Davids, Oldenberg and Beal have supplied several useful indications. The vastness of this many-sided subject, far beyond the scope of individual experience, the backward state of our knowledge on many points, the peculiar difficulties that beset the research, and the conditions under which the greater part of the book was written — in the scant leisure of a busy official life — these considerations may, I trust, excuse the frequent crudeness of treatment, as well as any errors which may be present, for I cannot fail to have missed the meaning occasionally, though sparing no pains to ensure accuracy. But, if my book, not- withstanding its shortcomings, proves of real use to those seeking information on the Buddhism of Tibet, as well as on the later Indian developments of Buddhism, and to future workers in these fields, I shall feel amply rewarded for all my labours.

L. Austine Waddell.

London,

31st October, 1894.

CONTENTS.

Preface I. Introductory — Division of Subject 1-4

A. HISTORICAL

II. Changes in Primitive Buddhism Leading to Lāmaism 5-17 III. Rise, Development and Spread of Lāmaism. 18-53 IV. Two sects of Lāmaism 54-75

B. DOCTRINAL.

V. Metaphysical Sources of the Doctrine 76-131 VI. The Doctrine and its Morality 132-154 VII.SCRIPTURES AND LITERATURE 155-168

C. MONASTIC.

VIII. The Order of Lāmas 169-211 IX. Daily Life and Routine … 212-225 X. Hierarchy and Re-incarnate Lāmas 226-254

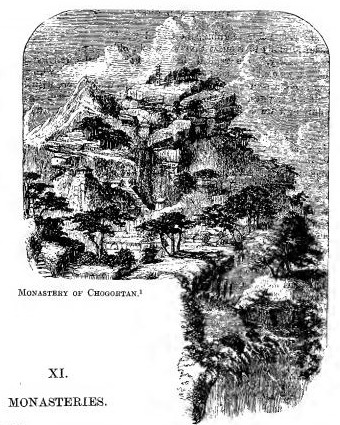

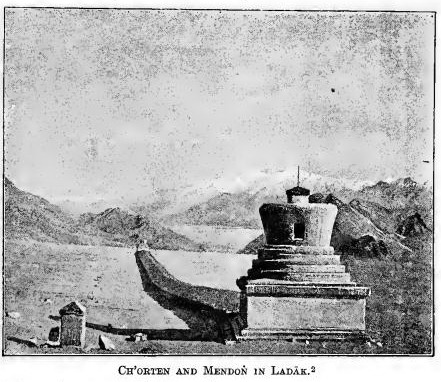

D. BUILDINGS.

XI. Monasteries 255-286 XII. Temples and Cathedrals 287-304 XIII. Shrines and Relics (And Pilgrims) 305-323

E. MYTHOLOGY AND GODS.

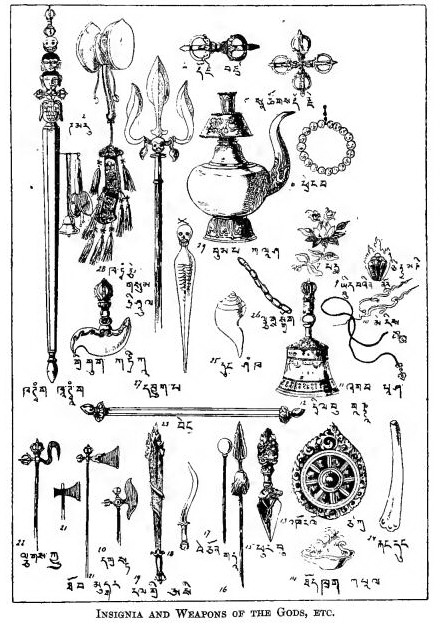

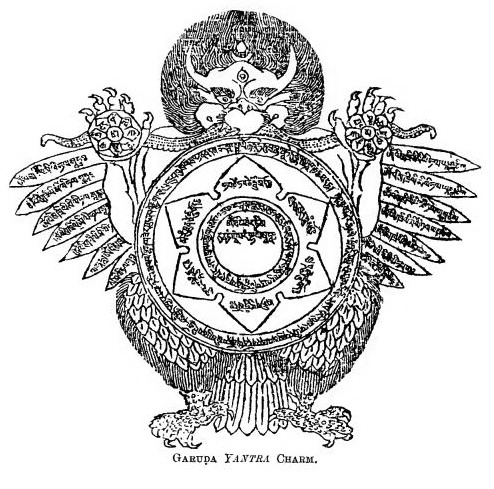

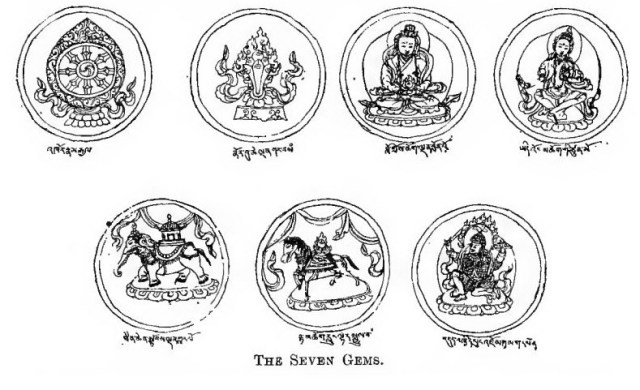

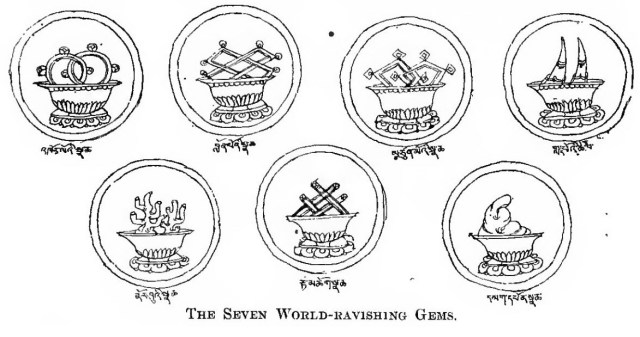

XIV. PANTHEON AND IMAGES 324-386 XV. SACRED SYMBOLS AND CHARMS. 387-419

F. RITUAL AND SORCERY

XVI. Worship and Ritual 420-449 XVII. Astrology and Divination 450-474 XVIII. Sorcery and Necromancy. 475-500

G. FESTIVALS AND PLAYS

XIX. Festivals and Holidays … 501-514 XX. Sacred Dramas, Mystic Plays and Masquerades. 515-565

II.POPULAR LAMAISM

XXI. Domestic and Popular Lamaism 566-573

APPENDICES

PRONUNCIATION. The general reader should remember as a rough rule that in the oriental names the vowels are pronounced as in German, and the consonants as in English, except c which is pronounced as ” ch,” ṅ as ” ng ” and ñ as ” ny.” In particular, words like Buddha are pronounced as if spelt in English ” Bood-dha,” Sākya Muni as ” Sha-kya Moo-nee,” and Karma as ” Kur-ma.” The spelling of Tibetan names is peculiarly uncouth and startling to the English reader. Indeed, many of the names as transcribed from the vernacular seem unpronounceable, and the difficulty is not diminished by the spoken form often differing widely from the written, owing chiefly to consonants having changed their sound or dropped out of speech altogether, the so-called ” silent consonants.” ‘ Thus the Tibetan word for the border-country which we, following the Nepalese, call Sikhim is spelt ‘bras-ljoṅs, and pronounced ” Den-jong,” and bk-ra-s’is is “Ta-shi.” When, however, I have found it necessary to give the full form of these names, especially the more important words translated from the Sanskrit, in order to recover their original Indian form and meaning, I have referred them as far as possible to footnotes.

1 Somewhat analogous to the French ils parlent. 2 The exceptions mainly are those requiring very specialized diacritical marks, the letters which are there (Jaeschke’s Dict., p. viii.), pronounced ga as a prefix, cha, nya”. the ha in several forms as the basis for vowels ; these I have rendered by g, ch’ ñ and ‘ respectively. In several cases I have spelt words according to Csoma’s system, by which the silent consonants are italicized.

For the use of readers who are conversant with the Indian alphabets, and the system popularly known in India as “the Hunterian,” the following table, in the order in which the sounds are physiologically produced — an order also followed by the Tibetans — will show the system of spelling Sanskritic words, which is here adopted, and which it will be observed, is almost identical with that of the widely used dictionaries of Monier- Williams and Childers. The different forms used in the Tibetan for aspirates and palato-sibilants are placed within brackets : — (palatals) c(c’) ch(ch’) j jh ñ (cerebals) ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh ṇ (dentals) t th(t’) d dh n (labials) P ph(p’) b bh m (palato-sibil.) (ts) (ts’) (z & ds) (z’) y v r l (sibilants) ṣ sh(s’) s ABBREVIATIONS. B. Ac. Ptsbg. = Bulletin de la Classe Hist. Philol. de l’Academie de St. Petersbourg. Burn. I. — Burnouf’s Introd. au Budd.indien. Burn. II. = ” ” Lotus de bonne Loi. cf. = confer, compare. Csoma An. = Csoma Korosi Analysis in Asiatic Researches Vol.XX Csoma Gr. = ” ” Tibetan Grammar. Davids = Rhys Davids’ Buddhism. Desg. = Desgodins’ Le Tibet, etc. Eitel = Eitel’s Handbook of Chinese Buddhism, Jaesch. D. = Jaeschke’s Tibetan Dictionary. J.A.S.B. = Jour, of the Asiatic Soc. of Bengal. J.R.A.S. = Journal of the Royal Asiatic Soc, London. Hodgs. = Hodgson’s Essays on Lang., Lit., etc. Hue = Travels in Tartary, Tibet, etc., Hazlitt’s trans. Kopp n = Koppen’s Lāmaische Hier. Markham = Markham’s Tibet. Marco P. = Marco Polo, Yule’s edition. O.M. = Original Mitt. Ethnolog. Konigl. Museum fur Volkerkunde Berlin. Pander = Pander’s Das Pantheon, etc. pr. = pronounced. Rock. L. = Rockhill’s Land of the Lāmas. Rock. B. = „ Life of the Buddha, etc. Sarat = Saratcandra Dās. S.B.E. = Sacred Books of the East. Schlag. = E. Schlagintweit’s Buddhism in Tibet. Skt. = Sanskrit. S.R. = Survey of India Report. T. = Tibetan. Tāra. = Tāranātha’s Geschichte, etc., Schiefner’s trans. Vasil. = Vasiliev’s or Wassiljew’s Der Buddhismus.

INTRODUCTORY . .

TIBET, the mystic Land of the Grand Lāma, joint God and King of many Millions, is still the most impenetrable country in the world. Behind its icy barriers, reared round it by Nature herself, and almost insurmountable, its priests guard its passes jealously against foreigners Few Europeans have ever entered Tibet; and none for half a century have reached the sacred city. Of the travellers of later times who have dared to enter this dark land, after scaling its frontiers and piercing its passes, and thrusting themselves into its snow-swept deserts, even the most intrepid have failed to penetrate farther than the outskirts of its central province.And the information, thus perilously gained, has, with the exception of Mr. Rockhill’s, been almost entirely geographical, leaving the customs of this forbidden land still a field for fiction and romance.

TIBET, the mystic Land of the Grand Lāma, joint God and King of many Millions, is still the most impenetrable country in the world. Behind its icy barriers, reared round it by Nature herself, and almost insurmountable, its priests guard its passes jealously against foreigners Few Europeans have ever entered Tibet; and none for half a century have reached the sacred city. Of the travellers of later times who have dared to enter this dark land, after scaling its frontiers and piercing its passes, and thrusting themselves into its snow-swept deserts, even the most intrepid have failed to penetrate farther than the outskirts of its central province.And the information, thus perilously gained, has, with the exception of Mr. Rockhill’s, been almost entirely geographical, leaving the customs of this forbidden land still a field for fiction and romance.

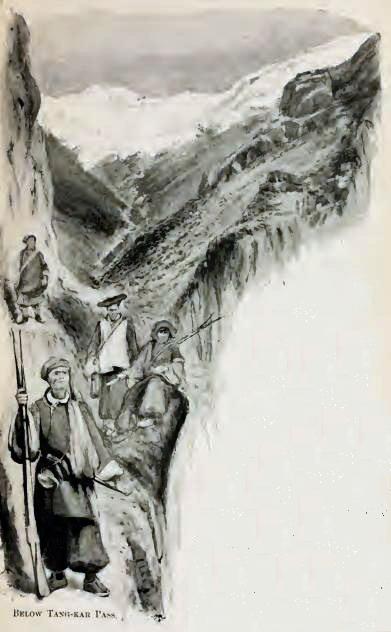

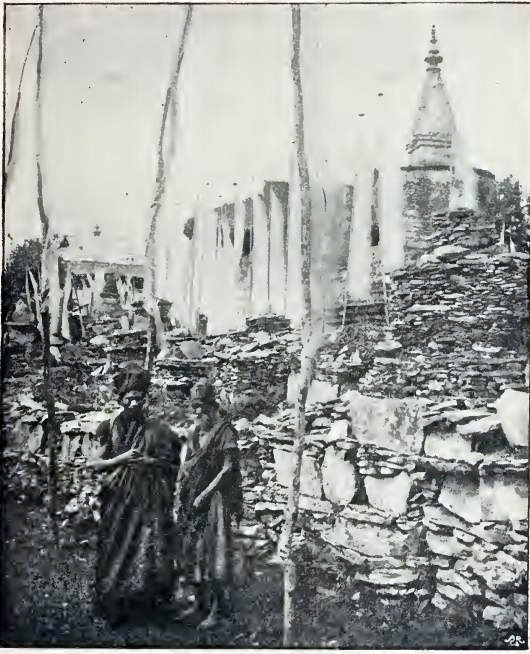

View into S.W. Tibet (from Tang-kar La Pass, 16,600ft.).

1 The Few Europeans who have penetrated Central Tibet have mostly been Roman missionaries. The first European to reach Lhāsa seems to have been Friar Odoric, of Pordenne, about 1330 A.D. on his return from Cathay (Col. Yule’s “Cathay and the Road Thither”,I,149; and C. Markham’s Tibet, xlvi.). The capital city of Tibet referred to by him with its “Abassi ” or Pope is believed to have been Lhāsa. In 1661 the Jesuits Albert Dorville and Johann Gruher visited Lhāsa on their way from China to India.

In 1706 the Capuchine Fathers Josepho de Asculi and Francisco Marie de Toun penetrated to Lhāsa from Bengal, in 1716 the Jesuit Desideri reached it From Kashmir and Ladāk. In 1741 a Capuchine mission under Horacio de la Penna also succeeded in getting there, and the large amount of information collected by them supplied Father A. Giorgi with this material for his Alphabetum Tibetanum, published at Rome in 1762.

The friendly reception accorded this party created hopes of Lhāsa becoming a centre For Roman missionaries; and a Vicar apostolicus for Lhāsa is still nominated and appears in the “Annuario pontificio,” though of course he cannot reside within Tibet. In l81l Lhāsa was reached by Manning, a Friend of Charles Lamb, and the only Englishman who seems ever to have got there; For most authorities are agreed that Moorcroft, despite the story told to M, Hue, never reached it. But Manning unfortunately left only a whimsical diary, scarcely even descriptive of his fascinating adventures. The subsequent, and the last, Europeans to reach Lhāsa were the Lazarist missionaries, Hue and Gabet, in 1845. Hue’s entertaining account of his journey is well known. He was soon expelled, and since then China has aided Tibet in opposing foreign ingress by strengthening its political and military barriers, as recent explorers : Prejivalskj , Rockhill, Bonvalot, Bower, Miss Taylor, etc, have found to their cost; though some are sanguine that the Sikhim Trade Convention of this year (1894)is probably the thin edge of the wedge to open up the country, and that no distant date Tibet will be prevailed on to relax its jealous exclusiveness, so that, ‘ere 1900, even Cook’s tourists may visit the Lāmaist Vatican.

Captain of the Guard of DONGXYA PASS. (S.-Western Tibet.) ; Thus we are told that, amidst the solitudes of this ” Land of the Supernatural ” repose the spirits of ” The Masters,” the Mahātmas, whose astral bodies slumber in unbroken peace, save when they condescend to work some petty miracle in the world below. In presenting here the actualities of the cults and customs of Tibet ; and lifting higher than before the veil which still hides its mysteries from European eyes, the subject may be viewed under the following sections: — a. Historical. The changes in primitive Buddhism leading to Lāmaism, and the origins of Lāmaism and its sects. b. Doctrinal. The metaphysical sources of the doctrine. The doctrine and its morality and literature. c. Monastic. The Lāmaist order. Its curriculum, daily life, dress, etc., discipline, hierarchy and incarnate-deities and reembodied saints. d. Buildings. Monasteries, temples, monuments, and shrines. e. Pantheon and Mythology, including saints, images. fetishes, and other sacred objects and symbols. f. Ritual and Sorcery, comprising sacerdotal services for the laity ,astrology, oracles and divination, charms and necromancy. g. Festivals and Sacred Plays, with the mystic plays and masquerades. h. Popular and Domestic Lāmaism in every-day life, customs, and folk-lore. Such an exposition will afford us a fairly full and complete survey of one of the most active, and least known, forms of existing Buddhism; and will present incidentally numerous other topics of wide and varied human interest. For Lāmaism is, indeed, a microcosm of the growth of religion and myth among primitive people; and in large degree an object -lesson of their advance from barbarism towards civilization. And it preserves for us much of the old-world lore and petrified beliefs of our Aryan ancestors.

Captain of the Guard of DONGXYA PASS. (S.-Western Tibet.) ; Thus we are told that, amidst the solitudes of this ” Land of the Supernatural ” repose the spirits of ” The Masters,” the Mahātmas, whose astral bodies slumber in unbroken peace, save when they condescend to work some petty miracle in the world below. In presenting here the actualities of the cults and customs of Tibet ; and lifting higher than before the veil which still hides its mysteries from European eyes, the subject may be viewed under the following sections: — a. Historical. The changes in primitive Buddhism leading to Lāmaism, and the origins of Lāmaism and its sects. b. Doctrinal. The metaphysical sources of the doctrine. The doctrine and its morality and literature. c. Monastic. The Lāmaist order. Its curriculum, daily life, dress, etc., discipline, hierarchy and incarnate-deities and reembodied saints. d. Buildings. Monasteries, temples, monuments, and shrines. e. Pantheon and Mythology, including saints, images. fetishes, and other sacred objects and symbols. f. Ritual and Sorcery, comprising sacerdotal services for the laity ,astrology, oracles and divination, charms and necromancy. g. Festivals and Sacred Plays, with the mystic plays and masquerades. h. Popular and Domestic Lāmaism in every-day life, customs, and folk-lore. Such an exposition will afford us a fairly full and complete survey of one of the most active, and least known, forms of existing Buddhism; and will present incidentally numerous other topics of wide and varied human interest. For Lāmaism is, indeed, a microcosm of the growth of religion and myth among primitive people; and in large degree an object -lesson of their advance from barbarism towards civilization. And it preserves for us much of the old-world lore and petrified beliefs of our Aryan ancestors.

CHANGES IN PRIMITIVE BUDDHISM LEADING TO LĀMAISM.

” Ah ! Constantine, of how much ill was cause,

Not thy conversion, but those rich domains

That the first wealthy Pope received of thee.” 1

TO understand the origin of Lāmaism and its place in the Buddhist system, we must recall the leading features of primitive Buddhism, and glance at its growth, to see the points at which the strange creeds and cults crept in, and the gradual crystallization of these into a religion differing widely from the parent system, and opposed in so many ways to the teaching of Buddha.  No one now doubts the historic character of Siddhārta Gautama, or Sākya Muni, the founder of Buddhism ;though it is clear the canonical accounts regarding him are overlaid with legend, the fabulous addition of after days. 2 Divested of its embellishment, the simple narrative of the Buddha’s life is strikingly noble and human. Some time before the epoch of Alexander the Great, between the fourth and fifth centuries before Christ, 3Prince Siddharta appeared in India as an original thinker and teacher, deeply conscious of the degrading thraldom of caste and the priestly tyranny of theBrāhmans

No one now doubts the historic character of Siddhārta Gautama, or Sākya Muni, the founder of Buddhism ;though it is clear the canonical accounts regarding him are overlaid with legend, the fabulous addition of after days. 2 Divested of its embellishment, the simple narrative of the Buddha’s life is strikingly noble and human. Some time before the epoch of Alexander the Great, between the fourth and fifth centuries before Christ, 3Prince Siddharta appeared in India as an original thinker and teacher, deeply conscious of the degrading thraldom of caste and the priestly tyranny of theBrāhmans

1. Dante, Paradiso, XX. (Milton’s trans.) 2 See Chapter V. for details of the gradual growth of the legends.3 See Chronological Table, Appendix i.

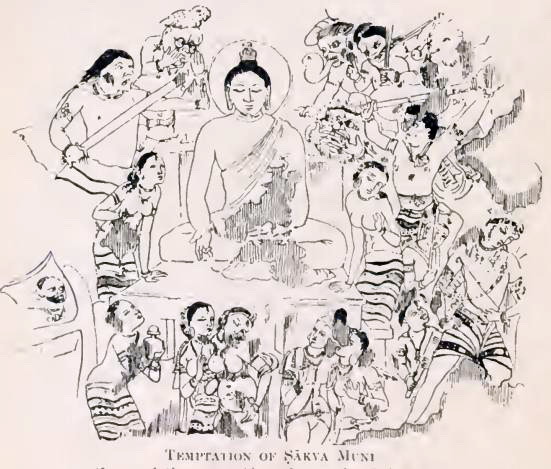

1 and profoundly impressed with the pathos and struggle of Life, and earnest in the search of some method of escaping from existence which was clearly involved with sorrow. His touching renunciation of his high estate,2 of his beloved wife, and child. and home, to become an ascetic, in order to master the secrets of deliverance from sorrow; his unsatisfying search for truth amongst the teachers of his time ; his subsequent austerities and severe penance, a much-vaunted means of gaining spiritual insight; his retirement into solitude and self-communion; his last struggle and final triumph — latterly represented as a real material combat, the so-called “Temptation of Buddha”: —

(from a sixth century Ajanta fresco, after Raj. Mitral.)

1 The treatises on Vedic ritual, called the Brahmanas, had existed for about three centuries previous to Buddha’s epoch, according to Max Muller’s Chronology [ Hibbert Lectures.1891,p58] the initial dates there given are Rig Veda, tenth century B.C. ; Brahmanas, eighth century B.C; Sutra sixth, and Buddhism fifth century B.C.

2 The researches of Vasiliev, etc., render it probable that Siddhartha’s father was only a petty lord or chief (cf. also OLDENBURG’S Life, Appendix), and that Sakya’s pessimistic view of Life may have been forced upon him by the loss of his territories through conquest by a neighbouring king,

3.Milton’s Paradise Regained, Book IV

his reappearance, confident that he had discovered the secrets of deliverance ; his carrying the good tidings of the truth from town to town; his effective protest against the cruel sacrifices of the Brahmans, and his relief of much of the suffering inflicted upon helpless animals and often human beings, in the name of religion ; his death, full of years and honours, and the subsequent

Buddha’s Death (from a Tibetan picture, after Grunwedel).

burial of his relics,— all these episodes in Buddha’s life are familiar to English readers in the pages of Sir Edwin Arnold’s Light of Asia, and other works. His system, which arose as a revolt against the one-sided development of contemporary religion and ethics, the caste-debasement of man and the materializing of God, took the form, as we shall see, of an agnostic idealism, which threw away ritual and sacerdotalism altogether. Its tolerant creed of universal benevolence, quickened by the bright example of a pure and noble life, appealed to the feelings of the people with irresistible force and directness, and soon gained for the new religion many converts in the Ganges Valley. And it gradually gathered a brotherhood of monks, which after Buddha’s death became subject to a succession of “Patriarchs,” 1 who, however, possessed little or no centralized hierarchical power, nor, had at least the earlier of them, any fixed abode. About 250 B.C. it was vigorously propagated by the great Emperor Asoka, the Constantine of Buddhism, who, adopting it as his State-religion, zealously spread it throughout his own vast empire, and sent many missionaries into the adjoining lands to diffuse the faith. Thus was it transported to Burma, 2 Siam, Ceylon, and other islands on the south, to Nepal 3 and the countries to the north of India, Kashmir, Bactria, Afghanistan, etc.

l The greatest of all Buddha’s disciples, Ṣāriputra and Mandgalyayāna, who from their prominence in the system seem to have contributed materially to its success,having died before their master , the first of the patriarchs was the senior surviving disciple, Mahākāṣyapa. As several of these Patriarchs are intimately associated with the Lāmaist developments, I subjoin a list of their names, taken from the Tibetan canon and Tāranātha’s history, supplemented by some dates from modern sources.After Nāgārjuna, the thirteenth (or according to some the fourteenth) patriarch, the succession is uncertain.

List of the Patriarchs.

1. Mahākāṣyapa, Buddha’s senior disciple

2. Ananda, Buddha’s cousin and favourite attendant.

3. Ṣaṇāvāsu.

4. Upagupta, the spiritual adviser of Asoka,250 B.C

5. Dhṛiṭaka.

6. Micchaka or Bibhakala.

7. Buddhananda.

8. Buddhamitra (=? Vasumitra, referred to as president of Kanishka’a Council).

9. Pārṣva, contemporary of Kanishka, circa 78 CE.

10. Suṇaṣata (? or Puṇyayaṣas).

11. Aṣvaghosha, also contemporary of Kanishika circa 100 CE.

12. Maṣipala (Kapimala).

13. Nāgārjuna, ཀླུ་སྒྲུབ་ klu sgrub, circa 150-250 CE

14. Deva or Kānadeva.

15. Rāhulata (?).

16. Saṅghanandi.

17. Saṅkhayaseta

18. Kumarada.

19. Jayata.

20. Vasubandhu, circa 400 CE.

21. Manura.

22. Haklenayaṣas.

23. Siṅhalaputra.

24. Vaṣasuta.

25. Puṇyamitra.

26. Prajñatāra.

27. Bodhidharma, who visited China by sea in 526 CE.

2 By SONA and UTTARO (Mahavamso p. 71). 3 BUCHANAN-HAMILITON (acct. of Nepal, p.190) gives dates of introduction as A.D.33; probably this was its reintroduction. 4. During the reign of the Emperor Ming Ti . BEAL (Budd.in China, p 58) gives date of introduction as 71 A.D

___________________________

in the sixth century A.D., to Japan, taking strong hold on all of the people of these countries, though they were very different from those among whom it arose, and exerting on all the wilder tribes among them a very sensible civilizing influence. It is believed to have established itself at Alexandria. 1 And it penetrated to Europe, where the early Christians had to pay tribute to the Tartar Buddhist Lords of the Golden Horde ; and to the present day it still survives in European Russia among the Kalmaks on the Volga, who are professed Buddhists of the Lāmaist order. Tibet, at the beginning of the seventh century, though now surrounded by Buddhist countries, knew nothing of that religion, and was still buried in barbaric darkness. Not until about the year 640 A.D., did it first receive its Buddhism, and through it some beginnings of civilization among its people. But here it is necessary to refer to the changes in Form which Buddhism meanwhile had undergone in India. Buddha, as the central figure of the system, soon became invested with supernatural and legendary attributes. And as the religion extended its range and influence, and enjoyed princely patronage and ease, it became more metaphysical and ritualistic, so that heresies and discords constantly cropped up, tending to schisms, for the suppression of which it was found necessary to hold great councils. Of these councils the one held at Jalandhar, in Northern India, towards the end of the first century A.D., under the auspices of the Scythian King Kanishka, of Northern India, was epoch-making, for it established a permanent schism into what European writers have termed the ” Northern ” and ” Southern ” Schools : the Southern being now represented by Ceylon, Burma, and Siam ; and the Northern by Tibet, Sikhim, Bhutan, Nepal, Ladāk, China, Mongolia, Tartary, and Japan. This division, however, it must be remembered, is unknown to the Buddhists themselves, and is only useful to denote in a rough sort of way the relatively primitive as distinguished from the developed or mixed forms of the faith, with especial reference to their present-day distribution.

1 The Mahāvanso (Turnour’s ed.,p.171) notes that 30,000 Bhikshus, or Buddhist monks, came from “Alasadda,” considered to be Alexandria.

The point of divergence of these so-called “Northern” and “Southern” Schools was the theistic- Mahāyāna doctrine, which substituted for the agnostic idealism and simple morality of Buddha, a speculative theistic system with a mysticism of sophistic nihilism in the background. Primitive Buddhism practically confined its salvation to a select few; but the Mahayana extended salvation to the entire universe. Thus, from its large capacity as a ” Vehicle ” for easy, speedy, and certain attainment of the state of a Bodhisattva or potential Buddha, and conveyance across the sea of life (saṃsāra) to Nirvāṇa, the haven of the Buddhists, its adherents called it “The Great Vehicle” or Mahāyāna ; l while they contemptuously called the system of the others— the Primitive Buddhists, who did not join this innovation — ” The Little or Imperfect Vehicle,” the Hinayāna,2 which could carry so few to Nirvāṇa, and which they alleged was only fit for low intellects. This doctrinal division into the Mahāyāna and Hinayāna, however, does not quite coincide with the distinction into the so-called Northern and Southern Schools; for the Southern School shows a considerable leavening with Mahāyāna principles,3 and Indian Buddhism during its most popular period was very largely of the Mahāyāna type. Who the real author of the Mahāyāna was is not yet known. The doctrine seems to have developed within the Mahā-saṅghika or “Great Congregation” — a heretical sect which arose among the monks of Vaisāli, one hundred years after Buddha’s death, and at the council named after that place. 4 Aṣvaghosha, who appears to have lived about the latter end of the first century CE., is credited with the authorship of a work entitled On raising Faith in the Mahāyāna. 5 But its chief expounder and developer was Nāgārjuna, who was probably a pupil of Aṣvaghosha, as he ____________________________

1 The word Yāna, (Tib., Teg-pa ch’en-po) or “Vehicle” is parallel to the Platonic δχμηα, is noted by BEAL in Catena, p.124. 2 Tib., Teg-pa dman-pa.3 Cf. HIUEN TSIANG’S Si-yu Ki (Beal’s), ii., p.133; EITEL, p. 90; Dharmapāla in Mahā bodhi Jour., 1892; Taw Sein Ko, Ind. Antiquary, June, 1892. 4 The orthodox members of this council formed the sect called Sthaviras or “elders.” 5 He also wrote a biography of Buddha, entitled Buddha-Carita Kārya, translated by Cowell, in S.B.E. It closely resembles the Lalita Vistara, and a similar epic was brought to China as early as 70 A.D. (Beal’s Chinese Buddhism, p. 90). He is also credited with the authorship of a clever confutation of Brāhmanism, which was latterly entitled Vajra Sūci (Cf. Hodgs., III., I27).

___________________________

followed the successor of the latter in the patriarchate. He could not, however, have taken any active part in Kanishka’s Council, as the Lāmas believe. Indeed, it is doubtful even whether he had then been born. 1 Nāgārjuna claimed and secured orthodoxy for the Mahāyāna doctrine by producing an apocalyptic treatise which he attributed to Sākya Muni, entitled the Prajñāpāramitā, or ” the means of arriving at the other side of wisdom,” a treatise Which he alleged the Buddha Nāgārjuna

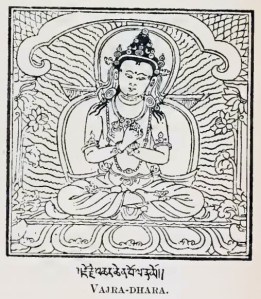

had himself composed, and had hid away in the custody of the Nāga demigods until men were sufficiently enlightened to comprehend so abstruse a system. And, as his method claims to be a compromise between the extreme views then held on the nature of Nirvāṇa,it was named the Mādhyamika, or the system “of the Middle Path.” 2 This Mahayana doctrine was essentially a sophistic nihilism ; and under it the goal Nirvāṇa, or rather Pari- Nirvāṇa, while ceasing to be extinction of Life, was considered a mystical state which admitted of no definition.By developing the supernatural side of Buddhism and its objective symbolism, by rendering its

had himself composed, and had hid away in the custody of the Nāga demigods until men were sufficiently enlightened to comprehend so abstruse a system. And, as his method claims to be a compromise between the extreme views then held on the nature of Nirvāṇa,it was named the Mādhyamika, or the system “of the Middle Path.” 2 This Mahayana doctrine was essentially a sophistic nihilism ; and under it the goal Nirvāṇa, or rather Pari- Nirvāṇa, while ceasing to be extinction of Life, was considered a mystical state which admitted of no definition.By developing the supernatural side of Buddhism and its objective symbolism, by rendering its

1 Nāgārjuna(T., kLu-grub.) appears to belong to the second century CE. He was a native of Vidarbha (Berar) and a monk of Nālanda, the headquarters of several of the later patriarchs. He is credited by the Lāmas (J.A.S.B., 1882, 115) with having erected the stone railing round the great Gandhola Temple of “Budh Gāya,” though the style of the lithic inscriptions on these rails would place their date earlier. For a biographical note from the Tibetan by H. Wenzel, see .J. Pali Text Soc., 1880, p. 1, also by Sarat, J.A.S.B;., 51, pp. l and 115. The vernacular history of Kashmīr (Rājatāranginī) makes him a contemporary and chief monk of Kanishka’s successor, King Abhimanyu (cf. also Eitel, p. 103; Schl., 21, 301-3; Kopp., ii., 14 ; O.M., 107, 2; Csoma, Gr., xii., 182).

2 It seems to have been a common practice for sectaries to call their own system by this title, implying that it only was the true or reasonable belief. Sākya Muni also called his system “the Middle Path*’ (Davids, p. 47). claiming in his defense of truth to avoid the two extremes (of superstition on the one side, and worldliness or infidelity on the other. Comp. the Via media of the Anglican Oxford movement.

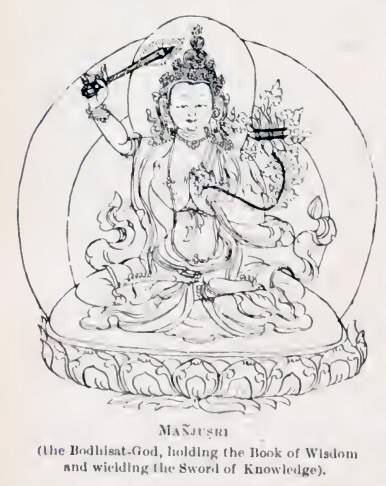

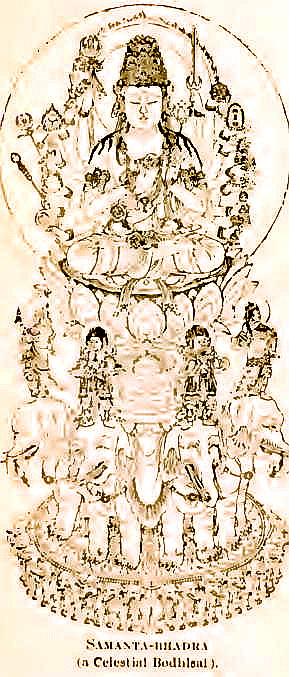

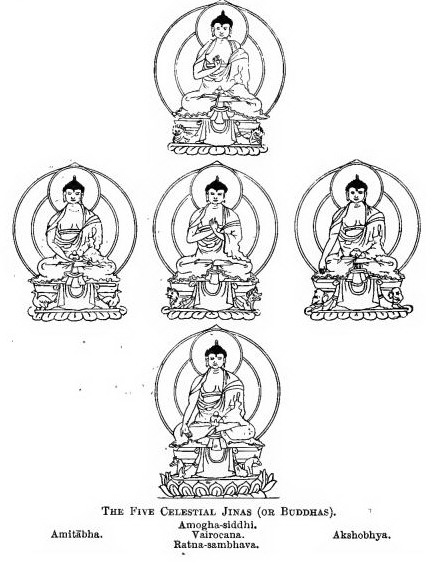

salvation more accessible and universal, and by substituting good words for the good deeds of the earlier Buddhists, the Mahāyāna appealed more powerfully to the multitude and secured ready popularity. About the end of the first century of our era, then, Kanishka’s Council affirmed the superiority of the Mahāyāna system, and published in the Sanskrit language inflated versions of the Buddhist Canon, from sources for the most part independent of the Pāli versions of the southern Buddhists, though exhibiting a remarkable agreement with them. 1 And this new doctrine supported by Kanishka, who almost rivaled Asoka in his Buddhist zeal and munificence, became a dominant form of Buddhism throughout the greater part of India ; and it was the form which first penetrated, it would seem, to China and Northern Asia.Its idealization of Buddha and his attributes led to the creation of metaphysical Buddhas and celestial Bodhisattva s, actively willing and  able to save, and to the introduction of innumerable demons and deities as objects of worship, with their attendant idolatry and sacerdotalism, both of which departures Buddha had expressly condemned. The gradual growth of myth and legend, and of the various set in, are sketched in theistic developments which now detail in another chapter.

able to save, and to the introduction of innumerable demons and deities as objects of worship, with their attendant idolatry and sacerdotalism, both of which departures Buddha had expressly condemned. The gradual growth of myth and legend, and of the various set in, are sketched in theistic developments which now detail in another chapter.

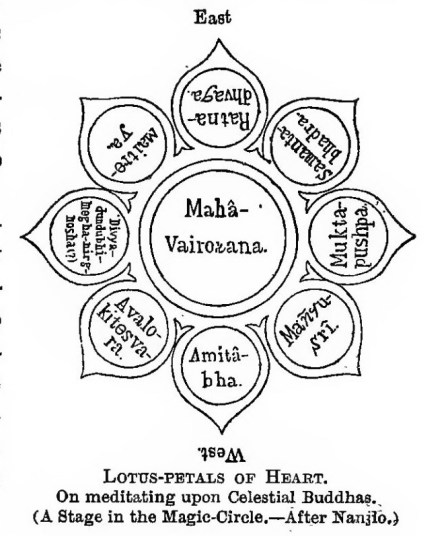

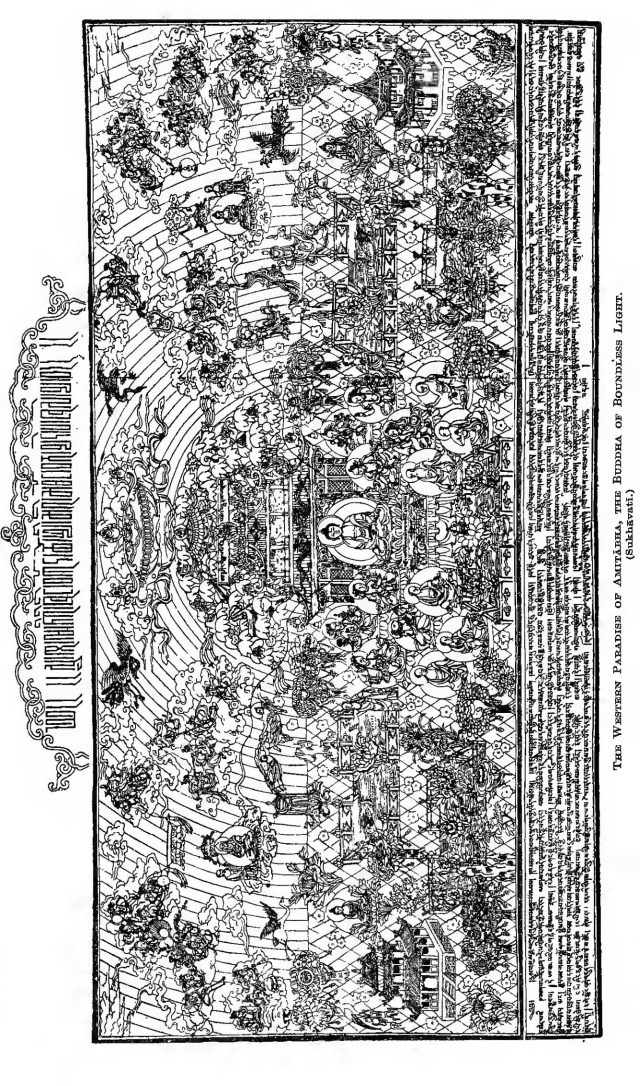

As early as about the first century CE., Buddha is made to be existent from all eternity and without beginning And one of the earliest forms given to the Greatest of these metaphysical Buddhas — Amitābha, The Buddha of Boundless Light

1. Several of the Chinese and Japanese Scriptures are translated from the Pāli in BEAL’s Buddhism in China p.50 and also a few Tibetan (Cf. Chap.VII)

— evidently incorporated a Sun-myth, as was indeed to be expected where the chief patrons of this early Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Scythian s and In-do-Persians, were a race of Sun-worshippers. The worship of Buddha’s own image seems to date from this period, the first century of our era, and about four or five centuries after Buddha’s death ;1 and it was followed by a variety of polytheistic forms, the creation of which was probably facilitated by the Grecian Art influences then prevalent in Northern India.2 The worship of Buddha’s own image seems to date from this period, the first century of our era, and about four or five centuries after Buddha’s death ;1 and it was followed by a variety of polytheistic forms, the creation of which was probably facilitated by the Grecian Art influences then prevalent in Northern India.2  Different forms of Buddha’s image, his life, were afterwards idealized into originally intended to represent different epochs in various Celestial Buddhas, from whom the human Buddhas were held to be derived as material reflexes. About 500 CE. 3 arose the next great Development in Indian Buddhism with the importation into it of the pantheistic cult of Yoga, or the ecstatic union of the individual with the Universal Spirit, a cult which had been introduced into Hinduism by Patanjali about 150 B.C. Buddha himself had attached much importance to the practice of

Different forms of Buddha’s image, his life, were afterwards idealized into originally intended to represent different epochs in various Celestial Buddhas, from whom the human Buddhas were held to be derived as material reflexes. About 500 CE. 3 arose the next great Development in Indian Buddhism with the importation into it of the pantheistic cult of Yoga, or the ecstatic union of the individual with the Universal Spirit, a cult which had been introduced into Hinduism by Patanjali about 150 B.C. Buddha himself had attached much importance to the practice of

VAJRA-PĀṆI(the Wielder of the Thunderbolt )

1.Cf. statue of Buddha found at Ṣrvāsti, Cunningham’s Stupa of Barhut, p. vii. So also in Christianity, Archdeacon Farrar, in his recent lecture on “The Development of Christian Art.” states that for three centuries there were no pictures of Christ, but only symbols, such as the fish, the lamb, the dove.The catacombs of St. Callistus contained the first picture of Christ, the date being 313. Not even a cross existed in the early catacombs, and still less a crucifix. The eighth century saw the first picture of the dead Christ. Rabulas in 586 first depicted the crucifixion in a Syriac Gospel. 2 SMITH’s Greco-Roman infl. on Civilization of Ancient India, J. A. S.B., 58 et seq.. 1889, and GRUNWEDEL’s Buddh. Kunst. 3 The date of the author of this innovation, Asaṅga, the brother of Vasubandhu,

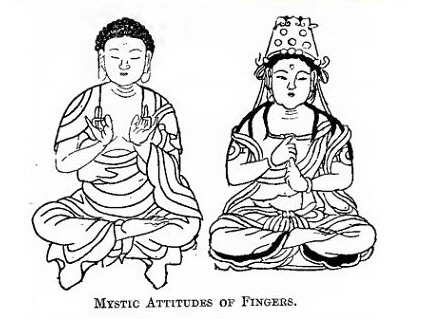

abstract meditation among-st his followers; and such practices under the mystical and later theistic developments of his system, readily led to the adoption of the Brāhmanical cult of Yoga, which was grafted on to the theistic Mahāyāna by Asaṅga, a Buddhist monk of Grandhārā (Peshawar), in Northern India. Those who mastered this system were called Yogācārya Buddhists. The Yogācārya mysticism seems to have leavened the mass of the Mahāyāna followers, and even some also of the Hinayāna; for distinct traces of Yoga are to be  found in modern Burmese and Ceylonese Buddhism. And this Yoga parasite, containing within itself the germs of Tantrism, seized strong hold of its host and soon developed its monster outgrowths, which crushed and cankered most of the little life of purely Buddhist stock yet Left in the Mahāyāna. About the end of the sixth century CE., Tantrism or Ṣivaic mysticism, with its worship of female energies, spouses of the Hindū god Ṣiva, began to tinge both Buddhism and Hindūism. Consorts were allotted to the several Celestial Bodhisattva and most of the other gods and demons, and most of them were given forms wild and terrible, and often monstrous, according to the supposed moods of each divinity at different times. And as these goddesses and fiendesses were bestowers of supernatural power, and were especially malignant, they were especially worshipped. By the middle of the seventh century CE., India contained many images of Divine Buddhas and Bodhisats with their female energies and other Buddhist gods and demons, as we know from Hiuen Tsiang’s narrative and the lithic remains in India; 1 and the growth of myth and ceremony had invested the dominant form of Indian Buddhism with organised litanies and full ritual.

found in modern Burmese and Ceylonese Buddhism. And this Yoga parasite, containing within itself the germs of Tantrism, seized strong hold of its host and soon developed its monster outgrowths, which crushed and cankered most of the little life of purely Buddhist stock yet Left in the Mahāyāna. About the end of the sixth century CE., Tantrism or Ṣivaic mysticism, with its worship of female energies, spouses of the Hindū god Ṣiva, began to tinge both Buddhism and Hindūism. Consorts were allotted to the several Celestial Bodhisattva and most of the other gods and demons, and most of them were given forms wild and terrible, and often monstrous, according to the supposed moods of each divinity at different times. And as these goddesses and fiendesses were bestowers of supernatural power, and were especially malignant, they were especially worshipped. By the middle of the seventh century CE., India contained many images of Divine Buddhas and Bodhisats with their female energies and other Buddhist gods and demons, as we know from Hiuen Tsiang’s narrative and the lithic remains in India; 1 and the growth of myth and ceremony had invested the dominant form of Indian Buddhism with organised litanies and full ritual.

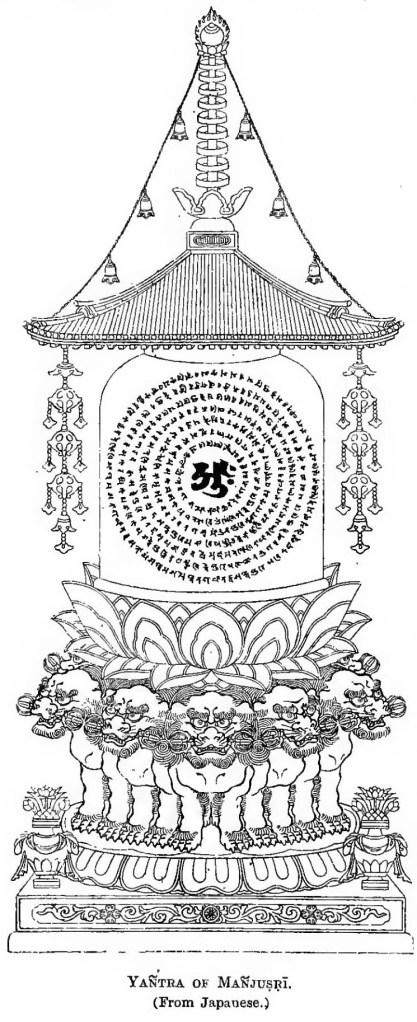

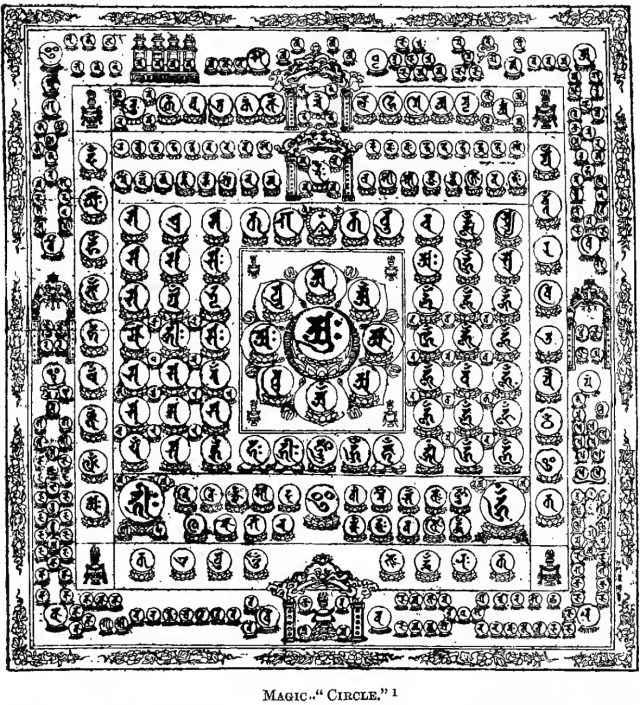

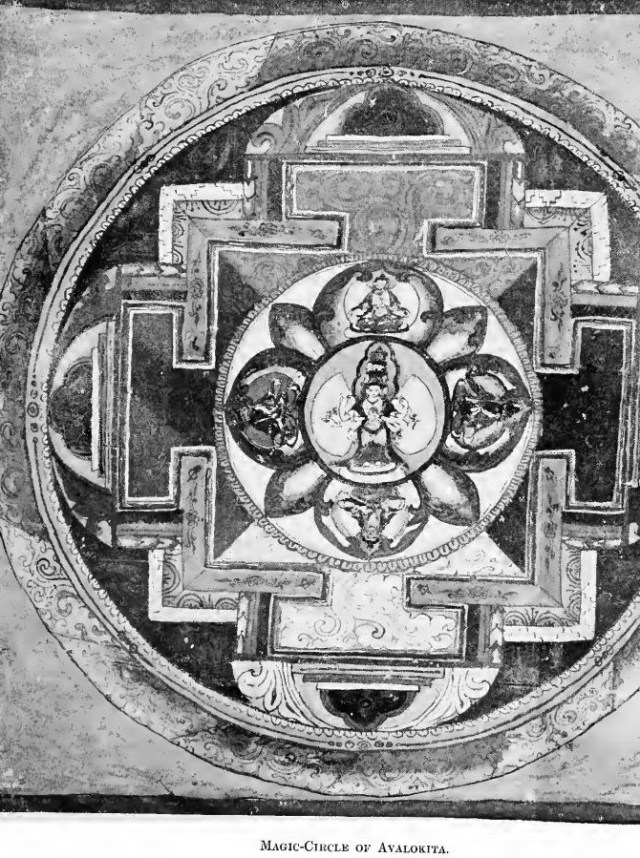

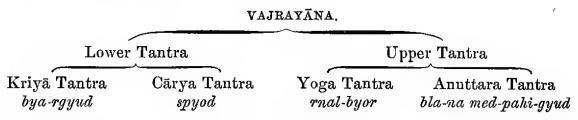

Such was the distorted form of Buddhism introduced into Tibet about 640 CE. ; and during the three or four succeeding centuries Indian Buddhism became still more debased. Its mysticism became a silly mummery of unmeaning jargon and ” magic circles,” dignified by the title of Mantrāyāna or “The Spell- Vehicle”; and this so-called ” esoteric,” but properly” exoteric,” cult

was given a respectable antiquity by alleging that its real founder was Nāgārjuna,who had received it from the Celestial Buddha Vairocana through the divine Bodhisat Vajrasattva at “the iron tower ” in Southern India. In the tenth century CE,’ 2 the Tantrik phase developed in Northern India, KashmĪr, and Nepal, into the monstrous and polydemonist doctrine, the Kālacākra,3 with its demoniacal Buddhas, which incorporated the Mantrāyāna practices, and called itself the Vajra-yāna, or “The Thunderbolt-Vehicle,” and its followers were named Vajrācārya, or ” Followers of the Thunderbolt”

was given a respectable antiquity by alleging that its real founder was Nāgārjuna,who had received it from the Celestial Buddha Vairocana through the divine Bodhisat Vajrasattva at “the iron tower ” in Southern India. In the tenth century CE,’ 2 the Tantrik phase developed in Northern India, KashmĪr, and Nepal, into the monstrous and polydemonist doctrine, the Kālacākra,3 with its demoniacal Buddhas, which incorporated the Mantrāyāna practices, and called itself the Vajra-yāna, or “The Thunderbolt-Vehicle,” and its followers were named Vajrācārya, or ” Followers of the Thunderbolt”

1 See my article on Uren, J.A.S.B., 1891, and on Indian Buddhist Cult, etc., in J.R.A.S., 1894, p. 51 et seq. 2 About 965 CE. (CS0MA, Gr., p. 192). 3 Tib., ‘Dus-Kyi-‘K’or-lo, or Circle of Time , see Chap. vi. It is ascribed to the fabulous country of Sambhala (T., De-juṅ) to the North of India, a mythical country probably founded upon the Northern land of St. Padma-Sambhava, to wit Udyāna,

In these declining days of Indian Buddhism, when its spiritual and regenerating influences were almost dead, the Muhammadan invasion swept over India, in the latter end of the twelfth century CE., and effectually stamped Buddhism out of the country. The fanatical idol-hating Afghan soldiery 1 especially attacked the Buddhist monasteries, with their teeming idols, and they massacred the monks wholesale;2 –

NĀRO (an Indian Buddhist Vajrācārya Monk of the Eleventh Century CE.).

and as the Buddhist religion, unlike the more domestic Brāhmanism, is dependent on its priests and monks for its vitality, it soon disappeared in the absence* of these latter. It lingered only for a short rime longer in the more remote parts of the peninsula, to which the fiercely fanatical Muhammadans could not readily penetrate. 3 But it has now been extinct in India for several centuries, leaving, however, all over that country, a legacy of gorgeous architectural remains and monuments of decorative art, and its

l See article by me in J.A.S.B., LXVI., 1892, p. 20 et seq., illustrating this fanaticism and massacre with reference to Magadha and Asam. 2 Tabaqat-i-Nāsiri, Elliot’s trans., ii., 306, etc. 3 Tāranātha – says it still existed in Bengal till the middle of the fifteenth century CE., under the ” Chagala ” Raja, whose kingdom extended to Delhi and who was converted to Buddhism by his wife Be died in 1448 CE., and Prof. Bendall finds (Cat.Buddh.Skt. MSS. intr.p. iv)that Buddhist MSS. were copied in Bengal up to the middle of the fifteenth century, namely, to 1446. Cf. also his note in J.R.A.S.,New Series.,XX., 552, and mine in J.A.S.B. (Proc), February, 1893

living effect upon its apparent offshoot Jainism, and upon Brāhmanism, which it profoundly influenced for good. Although the form of Buddhism prevalent in Tibet, and which has been called after its priests ” Lāmaism,” is mainly that of the mystical type, the Vajra-yāna, curiously incorporated with Tibetan mythology and spirit-worship, still it preserves there, as we shall see, much of the loftier philosophy and ethics of the system taught by Buddha himself. And the Lāmas have the keys to unlock the meaning of much of Buddha’s doctrine, which has been almost inaccessible to Europeans.

1 From a photograph by Mr. Hoffman

III. RISE, DEVELOPMENT, AND SPREAD OF LĀMAISM.

TIBET emerges from barbaric darkness only with the dawn of its Buddhism, in the seventh century of our era. Tibetan history, such as there is — and there is none at all before its Buddhist era, nor little worthy of the name till about the eleventh century A..D. — is fairly clear on the point that previous to King Sron Tsan Gampo’s marriage in 638-641 CE., Buddhism was quite unknown in Tibet. 1 And it is also fairly clear on the point that Lāmaism did not arise till a century later than this epoch. Up till the seventh century Tibet was inaccessible even to the Chinese. The Tibetans of this prehistoric period are seen, from the few glimpses that we have of them in Chinese history about the end of the sixth century, 2 to have been rapacious savages and reputed cannibals, without a written language, 3 and followers of an animistic and devil-dancing or Shamanist religion, the Bön, resembling in many ways the Taoism of China.Early in the seventh century, when Muhammad (” Mahomet “) ________________

1 The historians so-called of Tibet wrote mostly inflated bombast, almost valueless for historical purposes. As the current accounts of the rise of Buddhism in Tibet are so overloaded with legend, and often inconsistent, I have endeavoured to sift out the more positive data from the mass of less trustworthy materials. I have looked into the more disputed historical points in the Tibetan originals, and, assisted by the living traditions of the Lāmas, and the translations provided by Rockhill and Bushell especially, but also by Schlagintweit, Sarat, and others, 1 feel tolerably confident that as regards the questions of the mode and date of the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet, and the founding of Lāmaism, the opinions now expressed are in the main correct.

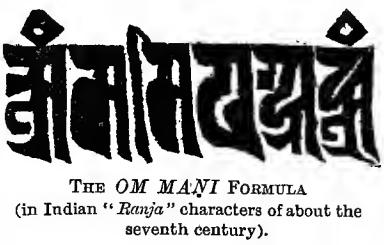

The accounts of the alleged Buddhist events in prehistoric Tibet given in the Maṇi-Kāh-‘bum, Gyal-rabs, and other legendary books, are clearly clumsy fictions. Following the example of Burma and other Buddhist nations (cf. Hiuen Tsiang, Julien’s trans., i., 179 ; ii., 107, etc.) who claim for their King an ancestry from the Sākya stock, we find the Lāmas foisting upon their King a similar descent. A mythical exiled prince, named gNah-K’ri-b Tsan-po, alleged to be the son of King Prasenjit, Buddha’s first royal patron, and a member of the Licchavi branch of the Ṣākya tribe, is made to enter Tibet in the fifth century B.C. as the progenitor of a millennium of Sroṅ Tsan Gampo’s ancestors; and an absurd story is invented to account for the etymology of his name, which means “the back chair”; while the Tibetan people are given as progenitors a monkey (” Hilumandju,” evidently intended for Hanumānji, the Hindu monkey god, cf. Rock., LL., 355) sent by Avalokiteṣwara and a rakshasi fiendess. Again, in the year 331 CE, there fell from heaven several sacred objects (conf. Rock., B., p. 210), including the Om mani formula, which in reality was not invented till many hundred (probably a thousand) years later. And similarly the subsequent appearance of five foreigners before a King, said to have been named T’o-t’ori Ñyan-tsan, in order to declare the sacred nature of the above symbols, without, however, explaining them, so that the people continued in ignorance of their meaning. And it only tends still further to obscure the points at issue to import into the question, as Lassen does (Ind. Alt., ii., 1072), the alleged erection on Mt. Kailās, in 137 B.C, of a temporary Buddhist monastery, for such a monastery must have belonged to Kashmir Buddhism, and could have nothing to do with Tibet, 2 Bushell, loc. cit, p. 435. They used knotched wood and knotted cords (Remusat’s Researches, p. 384,

was founding his religion in Arabia, there arose in Tibet a warlike king, who established his authority over the other wild clans of central Tibet, and latterly his son, Sroṅ Tsan Gampo, 1 harassed the western borders of China; so that the Chinese Emperor T’aitsung, of the T’ang Dynasty, was glad to come to terms with this young prince, known to the Chinese as Ch’itsung-luntsan, and gave him in 641 CE. 2 the Princess 3 Wench’eng, of the imperial house, in marriage. 4 Two years previously Sroṅ Tsan Gampo had married Bhṛikuṭi, a daughter of the Nepal King, Aṃṣuvarman ; 5 and both of these wives being bigoted Buddhists, they speedily effected the conversion of their young husband, who was then, according ________________ 1 Called also, prior to his accession (says Rockhill, Life, p. 211) Khri-ldan Sroṅ -btsan (in Chinese, Ki-tsung hm-tsan). His father, g’Nam-ri Sroṅ -tsan, and his ancestors had their headquarters at Yar-luṅ, or “the Upper Valley,” below the Yar-lha sam-po, a mountain on the southern confines of Tibet, near the Bhutan frontier. The Yar-luṅ river flows northwards into the Tsang-po, below Lhāsa and near Samye. This Yar-luṅ is to be distinguished from that of the same name in the Kham province, east of Bathang, and a tributary of the Yangtse Kiang. The chronology by Bu-ton (t’am-c’ad K’an-po) is considered the most reliable, and Sum-pa K’an-po accepted it in preference to the Baidyur Kar-po, composed by the Dalai Lāma’s orders, by De-Srid Saṅ-gyas Gya-mts’o, in 1686. According to Bu-ton, the date of Sroṅ Tsan Gampo’s birth was 617 CE. (which agrees with that given by the Mongol historian, Sasnang Setzen), and he built the palace Pho-daṅ-Marpo on the Lhāsa hill when aged nineteen, and the Lhāsa Temple when aged twenty-three. He married the Chinese princess when he was aged nineteen, and he died aged eighty-two. The Chinese records, translated by Bushell, make him die early. Csoma’s date of 627 {Grammar, p. 183) for his birth appears to be a clerical error for 617. His first mission to China was in 634 (Bushell, J.R.A.S., New Ser., xii., p. 440). 2 According to Chinese annals (Bushell, 435), the Tibetan date for, the marriage is 639 (C, G.,p.183), that is, two years after his marriage with the Nepalese princess. 3 Kong-jo = “princess” in Chinese. 4 The Tibetan tradition has it that there were three other suitors for this princess’s hand, namely, the three greatest kings they knew of outside China, the Kings of Magadha, of Persia (sTag-zig), and of the Hor (Turki) tribes. See also Hodgson’s Ess. and Rockhill’s B., 213 ; (Csoma’s Gr., 196; Bodhimur, 338. 5 Aṃṣuvarman, or “Glowing Armour,” is mentioned by Hiuen Tsiang (Beal’s Ed. Si-yu-ki, ii-. p. 81) as reigning about 637, and he appears as a grantee in FLEET’s Corpus Insern. Ind. (iii., p. 190) in several inscriptions ranging from 635 to 650 a.d., from which it appears that he was of the Ṭhākurī dynasty and a feudatory of King of Harshavardhana of Kanauj, and on the death of the latter seems to have become independent. The inscriptions show that devi was a title of his royal ladies, and his 635 CE. inscription recording a gift to his nephew,a svāmin (an officer), renders it probable that he had then an adult daughter. One of his inscriptions relates to Sivaist lingas, but none are expressedly Buddhist. The inscription 635 was discovered by C. BENDALL. and published in Ind. Ant. for 1885, and in his Journey, pp. 13 and 73. Cf. also Ind. Ant., IX., 170, and his description of coins in Zeitchr. der Deutsch. to Tibetan annals, only about sixteen years of age, 1 and who, under their advice, sent to India, Nepal, and China for Buddhist books and teachers. 2 It seems a perversion of the real order of events to state, as is usually done in European books, that Sroṅ Tsan Gampo first adopted Buddhism, and then married two Buddhist wives. Even the vernacular chronicle, 3 which presents the subject in its most flattering form, puts into the mouth of Sroṅ Tsan Gampo, when he sues for the hand of his first wife, the Nepalese princess, the following words : ” I, the King of barbarous 4 Tibet, do not practise the ten virtues, but should you be pleased to bestow on me your daughter, and wish me to have the Law, 5 I shall practise the ten virtues with a five-thousand-fold body . . , though I have not the arts . . . if you so desire . . . I shall build 5,000 temples.” Again, the more reliable Chinese history records that the princess said ” there is no religion in Tibet “; and the glimpse got of Sroṅ Tsan in Chinese history shows him actively engaged throughout his life in the very un-Buddhist pursuit of bloody wars with neighbouring states. The messenger sent by this Tibetan king to India, at the instance of his wives, to bring Buddhist books was called Thonmi Sam-bhota. 6 The exact date of his departure and return are uncertain, 7 and although his Indian visit seems to have been within the period covered by Hiuen Tsiang’s account, this history makes no mention even of the country of Tibet, After a stay in India 8 of several years, during which Sam-bhota studied under the _____________

1 The Gyal-rabs Sel-wai Meloṅ states that S. was aged sixteen on his marriage with the Nepalese princess, who was then aged eighteen, and three years later’ he built his Pho daṅ-Marpo Palace on the Red Hill at Lhāsa. 2 The monks who came to Tibet during Sroṅ Tsan Gampo’s reign were Kusara (? Kumāra) and Saṅkara Brāhmana, from India ; Sila Mañju, from Nepal • Hwa shang Mahā-ts’e, from China, and (E.SCHLAGT., Gyal-rabs, p. 49) Tabuta and Ganuta from Kashmīr. 3 Mirror of Royal pedigree, Gyal-rabs Sel-wai Meloṅ. 4 mT’ah-‘k’ob. 5 K’rims. 6 Sambhota is the Sanskrit title for ” The good Bhotiya or Tibetan.” His proper name is Thon-mi, son of Anu. 7 632 CE. is sometimes stated as date of departure, and 650 as the return ; but on this latter date Sroṅ Tsan Gampo died according to the Chinese accounts, although he should survive for many (48) years longer, according to the conflicting Tibetan record. 8 “Southern India”(Bodimur; p. 327).

Brāhman Livikara or Lipidatta 1 and the pandit Devavid Siṅha (or Siṅha Ghosha), he returned to Tibet, bringing several Buddhist books and the so-called “Tibetan” alphabet, by means of which he now reduced the Tibetan language to writing and composed for this purpose a grammar. 2 This so-called “Tibetan” character, however, was merely a somewhat fantastic reproduction of the north Indian alphabet current in India at the time of Sam-bhota’s visit. It exaggerates the nourishing curves of the ” Kuṭila ” which was then coming into vogue in India, and it very slightly modified a few letters to adapt them to the peculiarities of Tibetan phonetics. 3 Thonmi translated into this new character several small Buddhist texts, 4 but he does not appear to have become a monk or to have attempted any religious teaching. Sroṅ Tsan Gampo , being one of the. greatest kings of Tibet and the first patron of learning and civilization in that country, and having with the aid of his wives first planted the germs of Buddhism in Tibetan soil, he is justly the most famous and popular king of the country, and latterly he was canonized as an incarnation of the most popular of the celestial Bodhisattvas, Avalokita ; and in keeping with this legend he is figured with his hair dressed up into a high conical chignon after the fashion of the Indian images of this Buddhist god, ” The Looking-down-Lord.” His two wives were canonized as incarnations of Avalokita’s consort, Tārā, “the Saviouress,” or Goddess of Mercy; and the fact that they bore him no children is pointed to as evidence of their divine nature. 5 The Chinese princess Wench’eng was deified

1 Li-byin = Li + “to give.” 2 sGrahi bstan bch’os sum ch’u-pa. 3 The cerebrals and aspirates not being needed for Tibetan sounds were rejected. And when afterwards the full expression of Sanskrit names in Tibetan demanded these letters, the live cerebrals were formed by reversing the dentals and the aspirates obtained by suffixing an h, -while the palato-sibilants ts, tsh, and ds were formed by adding a surmounting crest to the palatals ch, chh, and j. it is customary to say that the cursive style, the “headless” or U-med (as distinguished from the full form with the head the U-ch’en) was adapted from the sO-called “Wartu” form of Devanagri— Hodgson, As. Res.,XVI.,420; SCHMIDT, Mem. del’Ac.de Pet.,i.,41 ; CSOMA.Gr.,204 ; SARAT, J.A.S.B., 1888, 12. 4 The first book translated Seems to have been the Karanda-vyuha Sutra, a favourite in Nepal ; and a few other translations still extant in the Tan-gyur are ascribed to him (CSOMA, .A.. and ROCK.,B., 212. 5 His issue proceeded from two or four Tibetan wives.

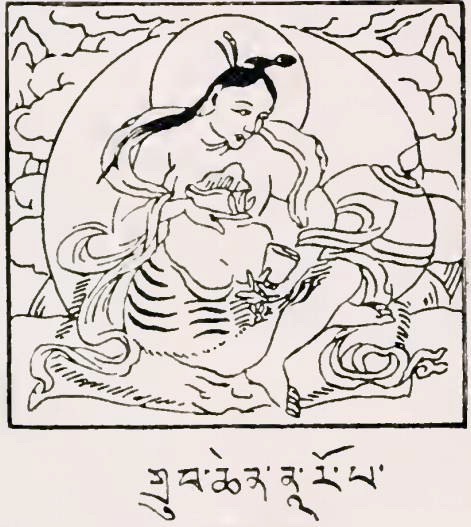

as ” The white Tāra,” 1 as in the annexed figure ; while the Nepalese princess “Bri-bsun” said to be a corruption of Bhṛikuṭi,was apotheosised as the green Bhṛi-kuṭi Tāra, 2 as figured in the chapter on the pantheon. But he was not the saintly person the grateful Lāmas picture, for he is seen from reliable Chinese history to have been engaged all his life in bloody wars, and more at home in the battlefield than the temple. And he certainly did little in the way of Buddhist propaganda, beyond perhaps translating a few tracts into Tibetan, and building a few temples to shrine the images received by him in dower, 3 and others which he constructed. He built no monasteries. Tara, the White. The Deified Chinese Princess Wench’eng.4

chapter on the pantheon. But he was not the saintly person the grateful Lāmas picture, for he is seen from reliable Chinese history to have been engaged all his life in bloody wars, and more at home in the battlefield than the temple. And he certainly did little in the way of Buddhist propaganda, beyond perhaps translating a few tracts into Tibetan, and building a few temples to shrine the images received by him in dower, 3 and others which he constructed. He built no monasteries. Tara, the White. The Deified Chinese Princess Wench’eng.4

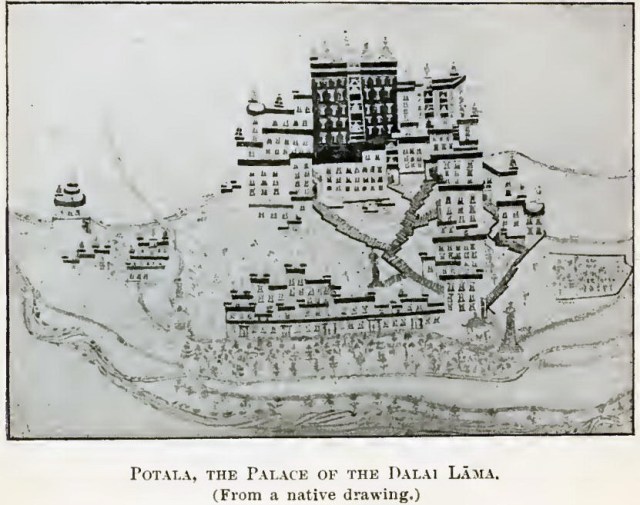

1 E. Schlagintweit (p. 66) transposes the forms of the two princesses, and most subsequent writers repeat his confusion. 2 She is represented to have been of a fiery temper, and the cause of frequent brawls on account of the precedence given to the Chinese princess. 3 He received as dower with the Nepalese princess, according to the Gyal-rabs, the images of Akshobhya Buddha, Maitreya and a sandal-wood image of Tāra ;and from his Chinese wife a figure of Ṣākya Muni as a young prince. To shrine the images of Akshobhya and the Chinese Ṣākya he built respectively the temples of Ramoch’e and another at Rāsa, now occupied by the Jo-wo K’an at Lhāsa. The latter temple was called Rasa-‘p’rul snan gi gtsug-lha-K ‘an, and was built in his twenty-third year, and four years after the arrival of the Chinese princess (in 644 CE., Bushell). The name of its site, Ra-sa, is said to have suggested the name by which it latterly became more widely known, namely, as Lhā-sa, or “God’s place.” The one hundred and eight temples accredited to him in the Mani-Kāh-‘bum are of course legendary, and not even their sites are known to the Lāmas themselves.

1 After Pander.

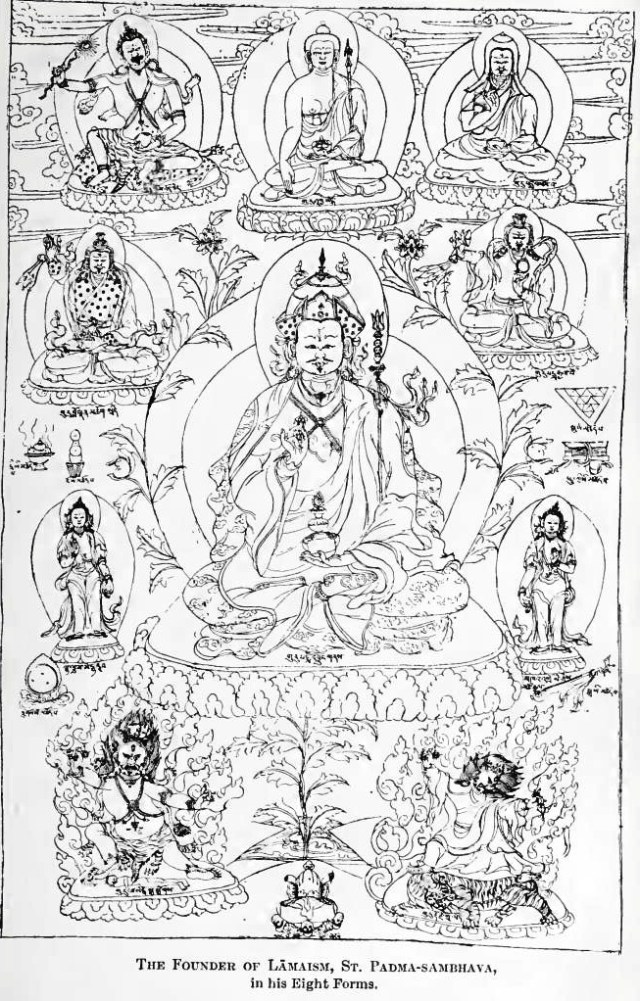

After Sroṅ Tsan Gampo’s death, about 650 CE.,1 Buddhism made little headway against the prevailing Shamanist superstitions, and seems to have been resisted by the people until about a century later in the reign of his powerful descendant Thi-Sroṅ Detsan, 2 who extended his rule over the greater part of Yunnan and Si-Chuen, and even took Changan, the then capital of China. This king was the son of a Chinese princess, 3 and inherited through his mother a strong prejudice in favour of Buddhism. He succeeded to the throne when only thirteen years old, and a few years later 4 . he sent to India for a celebrated Buddhist “King Thi-Sroṅ Detsan” priest King Thi- Sroṅ Detsan. to establish an order in Tibet; and he was advised, it is said, by his family priest, the Indian monk Ṣānta-rakshita, to secure if possible the services of his brother-in- law, 5 Guru Padma-sambhava, a clever member of the then popular Tantrik Yogācārya school, and at that time, it is said, a resident of the great college of Nālanda, the Oxford of Buddhist India. This Buddhist wizard, Guru Padma-sambhava, promptly responded to the invitation of the Tibetan king, and accompanied the messengers back to Tibet in 747 CE. 6 As Guru Padma-sambhava was the founder of Lāmaism, and is now deified and as celebrated in Lāmaism as Buddha himself, than whom, indeed, he receives among several sects more worship, he demands detailed notice.

the then capital of China. This king was the son of a Chinese princess, 3 and inherited through his mother a strong prejudice in favour of Buddhism. He succeeded to the throne when only thirteen years old, and a few years later 4 . he sent to India for a celebrated Buddhist “King Thi-Sroṅ Detsan” priest King Thi- Sroṅ Detsan. to establish an order in Tibet; and he was advised, it is said, by his family priest, the Indian monk Ṣānta-rakshita, to secure if possible the services of his brother-in- law, 5 Guru Padma-sambhava, a clever member of the then popular Tantrik Yogācārya school, and at that time, it is said, a resident of the great college of Nālanda, the Oxford of Buddhist India. This Buddhist wizard, Guru Padma-sambhava, promptly responded to the invitation of the Tibetan king, and accompanied the messengers back to Tibet in 747 CE. 6 As Guru Padma-sambhava was the founder of Lāmaism, and is now deified and as celebrated in Lāmaism as Buddha himself, than whom, indeed, he receives among several sects more worship, he demands detailed notice.

1 He was succeeded in 650 by his grandson Mang- Sroṅ-Mang-tsan under the regency of Sroṅ Tsan’s Buddhist minister, Gar (mk’ar), known to the Chinese as Chushih (BUSHELL, loc. cit., 446). 2 K’ri- Sroṅ Ideu-btsan. (Of. Kopp., ii., 67-72 ; Schlag., 67 ; J.A.S.B., 1881, p. 224.) ROCK.,B., quotes p. 221 contemporary record in bsTan-gyur (XCIV., f.387-391), proving that in Thi- Sroṅ Detsan’s reign in the middle of the eighth century, Tibet was hardly recognized as a Buddhist country. 3 Named Chin cheng (Tib., Kyim Shaṅ), adopted daughter of the Emperor Tchang tsong (BUSHELL, 456). 4 In 747 (Csoma,Gr.,183) ; but the Chinese date would give 755 (BUSHELL). 5 The legendary life of the Guru states that he married the Princess Mandāravā, a sister of Ṣānta-rakshita. 6 Another account makes the Guru arrive in Tibet in anticipation of the king’s wishes.

The Founder of Lāmaism, St. Padma-sambhava, in his Eight Forms.

is usually called by the Tibetans Guru Rin-po-ch’e, or ” the precious Guru ” ; or simply Lo-pon, 2 the Tibetan equivalent of the Sanskrit ” Guru ” or “teacher.” He is also called ” Ugyan” or ” Urgyan,” as he was a native of Udyāna or Urgyan, corresponding to the country about Ghazni 3 to the north-west of Kashmīr. Udyāna, his native land, was famed for the proficiency of its priests in sorcery, exorcism, and magic. Hiuen Tsiang, writing a century previously, says regarding Udyāna : ” The people are in disposition somewhat sly and crafty. They practise the art of using charms. The employment of magical sentences is with them an art and a study.” 4 And in regard to the adjoining country of Kashmīr also intimately related to Lāmaism, Marco Polo a few centuries later says : ” Keshimur is a province inhabited by people who are idolaters (i.e., Buddhists). . . . They have an astonishing acquaintance with the devilries of enchantment, insomuch as they can make their idols speak. They can also by their sorceries bring on changes of weather, and produce darkness, and do a number of things so extraordinary that no one without seeing them would believe them. Indeed, this country is the very original source from which idolatry has spread abroad.”5 The Tibetans, steeped in superstition which beset them on every side by malignant devils, warmly welcomed the Guru as he brought them deliverance from their terrible tormentors. Arriving in Tibet

acquaintance with the devilries of enchantment, insomuch as they can make their idols speak. They can also by their sorceries bring on changes of weather, and produce darkness, and do a number of things so extraordinary that no one without seeing them would believe them. Indeed, this country is the very original source from which idolatry has spread abroad.”5 The Tibetans, steeped in superstition which beset them on every side by malignant devils, warmly welcomed the Guru as he brought them deliverance from their terrible tormentors. Arriving in Tibet

1For legend of his birth from a lotus see p. 380. 2 sLob-dpon. 3 The Tibetans state that it is now named Ghazni, but Sir H. Yule, the great geographer, writes (MARCO P.,i.,155) : ” Udyāna lay to the north of Peshāwar, on the Swat river, but from the extent assigned to it by Hwen Thsang, the name probably covered a large part of the whole hill region south of the Hindu Kush, from Chitral to the Indus, as indeed it is represented in the Map of Vivien de St. Martin (Pelerins Bouddhistes, ii.).” It is regarded by Fahian as the most northerly Province of India, and in his time the food and clothing of the people were similar to those of Gangetic India.

4. BEAL’s Si-Yu-Ki, i.,120. 5 MARCO P., i., 155.

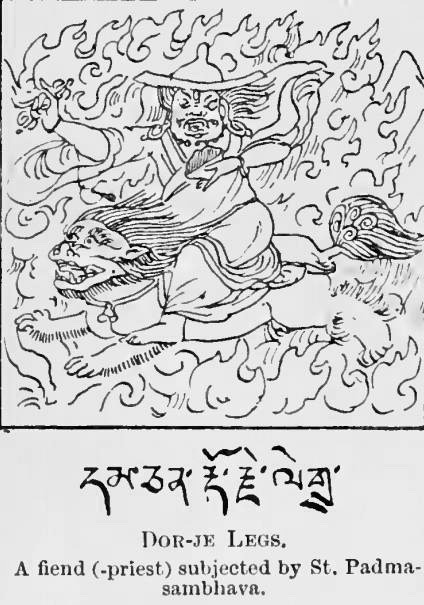

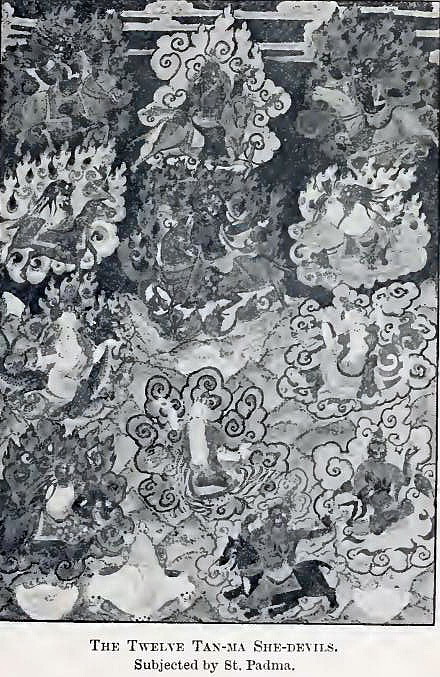

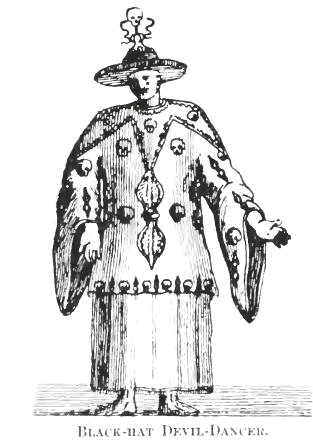

in 747 a.d., he vanquished all the chief devils of the land, sparing most of them on their consenting to become defenders of his religion, while he on his part guaranteed that in return for such services they would be duly worshipped and fed. Thus, just as the Buddhists in India, in order to secure the support of the semi- aborigines of Bengal admitted into their system the bloody Durga and other aboriginal demons, so on extending their doctrines throughout Asia they pandered to the popular taste by admitting within the pale of Buddhism the pantheon of those new nations

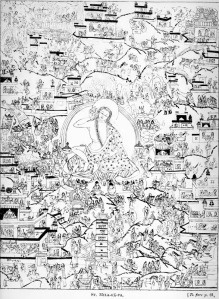

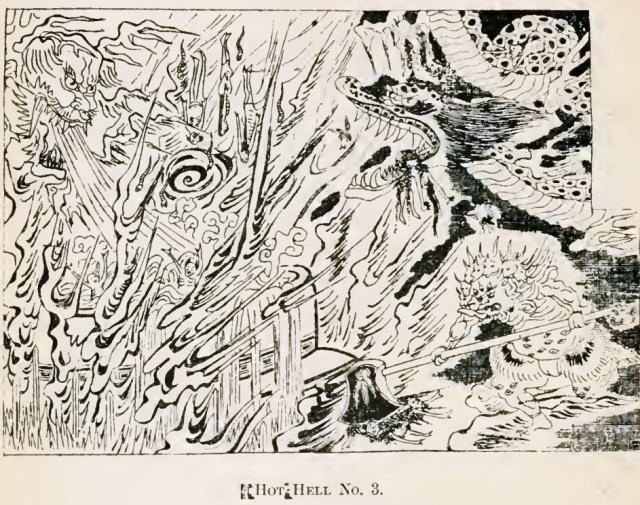

they sought to convert. And similarly in Japan, where Buddhism was introduced in the sixth century CE., it made little progress till the ninth century, when Kobo Daishi incorporated it with the local Shintoism, by alleging that the Shinto deities were embodiments of the Buddhist. The Guru’s most powerful weapons in warring with the demons were the “Vajra “ The Twelve Tan-ma She-devils. Subjected by St. Padma.(Tibetan, dor-je), symbolic of the thunderbolt of India (Jupiter), and spells extracted from the Mahāyāna gospels, by which he shattered his supernatural adversaries. As the leading events of his march through Tibet and his subjugation of the local devils are of some interest, as indicating the original habitats of several of the pre-Lāmaist demons, I have given a condensed account of these in the chapter on the pantheon at page 382.Under the zealous patronage of King Thi-Sroṅ Detsan he built at Sām-yās in 749 CE. the first Tibetan monastery. The orthodox account of the miraculous creation of that building is referred to in our description of that monastery. On the building of Sām-yās, 1 said to be modelled after the Indian Odantapura of Magadha, the Guru, assisted by the Indian monk  Ṣānta -rakshita, instituted there the order of the Lāmas. Ṣānta -rakshita was made the first abbot and laboured there for thirteen years. He now is entitled Acārya Bodhisat. 2 Lā-ma 3 is a Tibetan word meaning the ” Superior One,”and corresponds to the Sanskrit Uttara. It was restricted to the head of the monastery, and still is strictly applicable only to abbots and the highest monks; though out of courtesy the title is Indian Buddhist monk of the Eighth Century CE. now given to almost all Lāmaist monks and priests. The Lāmas have no special term for their form of Buddhism. They simply call it ” The religion ” or “Buddha’s religion”; and its professors are “Insiders,” or “within the fold” (naṅ -pa), in contradistinction to the non-Buddhists or “Out-siders ” (chi-pa or pyi-‘lin), the so-called ” pe-ling ” or foreigners of English writers. And the European term “Lāmaism” finds no counterpart in Tibetan.

Ṣānta -rakshita, instituted there the order of the Lāmas. Ṣānta -rakshita was made the first abbot and laboured there for thirteen years. He now is entitled Acārya Bodhisat. 2 Lā-ma 3 is a Tibetan word meaning the ” Superior One,”and corresponds to the Sanskrit Uttara. It was restricted to the head of the monastery, and still is strictly applicable only to abbots and the highest monks; though out of courtesy the title is Indian Buddhist monk of the Eighth Century CE. now given to almost all Lāmaist monks and priests. The Lāmas have no special term for their form of Buddhism. They simply call it ” The religion ” or “Buddha’s religion”; and its professors are “Insiders,” or “within the fold” (naṅ -pa), in contradistinction to the non-Buddhists or “Out-siders ” (chi-pa or pyi-‘lin), the so-called ” pe-ling ” or foreigners of English writers. And the European term “Lāmaism” finds no counterpart in Tibetan.

1 The title of the temple is Zan-yad Mi-gyur Lhun-gyi dub-pahi tsug-lha-Ksan, Or the “Self-sprung immovable shrine,” and it is believed to be based on immovable foundations of adamantine laid by the Guru. 2 And is said to have been of the Svatantra school, following Ṣāriputra, Ananda, Nāgārjuna, Subhaṅkara, Ṣrī Gupta, and Jñāna-garbha (cf. SCHL.,67; KOPP., ii., 68; J.A.S.B., 1881, p. 226; PAND., No. 25.) 3 bLa-ma. The Uighurs (?Hor) call their Lāmas “tain ” (YULE’s, Cathay, p. 211,note).

The first Lāma may be said to be Pal- baṅs, who succeeded the Indian abbot Ṣānta -rakshita ; though the first ordained member of this Tibetan order of monks was Bya-Khri-gzigs. 1 The most learned of these young Lāmas was Vairocana, who translated many Sanskrit works into Tibetan, though his usefulness was interrupted for a while by the Tibetan wife of Thi-Sroṅ Detsan ; who in her bitter opposition to the King’s reforms, and instigated by the Bonpa priests, secured the banishment of Vairocana to the eastern province of Kham by a scheme similar to that practised by Potiphar’s wife. But, on her being forthwith afflicted with leprosy, she relented, and the young « Bairo-tsana ” was recalled and effected her cure. She is still, however, handed down to history as the ” Red Rahulā she-devil,” 2 while Vairocana is made an incarnation of Buddha’s faithful attendant and cousin Ānanda ; and on account of his having translated many orthodox scriptures, he is credited with the composition or translation and hiding away of many of the fictitious scriptures of the unreformed Lāmas, which were afterwards ” discovered” as revelations. It is not easy now to ascertain the exact details of the creed the primitive Lāmaism— taught by the Guru, for all the extant works attributed to him “were composed several centuries later by followers of his twenty-five Tibetan disciples. But judging from the intimate association of his name with the essentials of Lāmaist sorceries, and the special creeds of the old unreformed section of the Lāmas— the Ñin-ma-pa— who profess and are acknowledged to be his immediate followers, and whose older scriptures date back to within two centuries of the Guru’s time, it is evident that his teaching was of that extremely Tāntrik and magical type of Mahāyāna Buddhism which was then prevalent in his native country of Udyān and Kashmīr. And to this highly impure form of Buddhism, already covered by so many foreign accretions and saturated with so much demonolatry, was added a

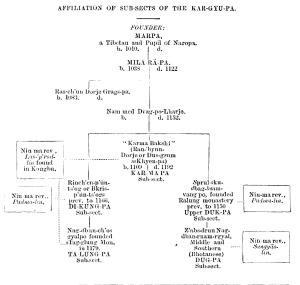

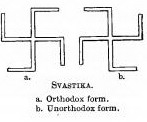

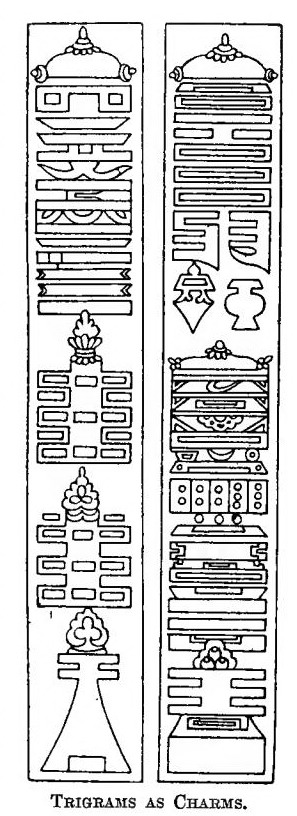

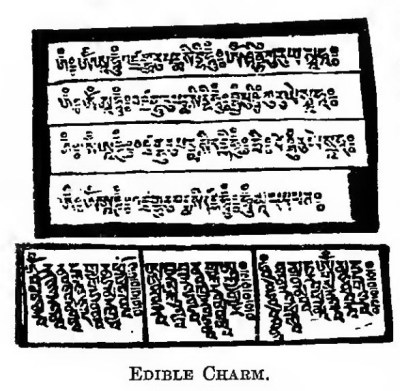

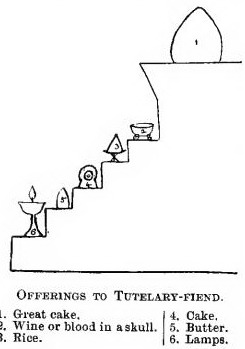

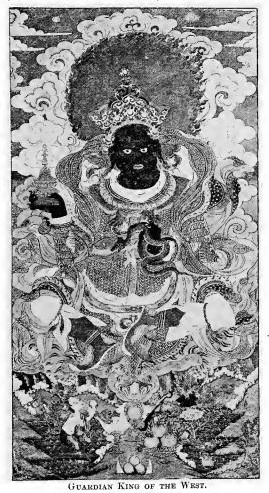

1 The first seven novices (Sad-mi mi) who formed the nucleus of the order were dBah dpal dbaṅs, rtsaṅs-devendra and Branka Mutik, ‘K’on Nāgendra, Sagor Vairocana, rMa Ācārya rin-ch’en mch’og, gLaṅ-Ka Tanana, of whom the first three were elderly. 2 gZa-mar gyal. The legend is given in the T’aṅ-yik Ser-t’en.