Greetings, BugFans,

Aphids

Today’s bug is the ubiquitous and very unassuming aphid. Aphids are Homopterans (No, the Bug Lady is not being any more politically incorrect than usual—aphids belong to the order Homoptera (same wing), which also includes the cicadas, treehoppers, leafhoppers, aphids and scales). Some enthusiastic entomologists lump the Homoptera with the nearby Hemiptera, or True bugs. Aphids come in a variety of colors (aphid green and aphid yellow and aphid red are popular) and, and with their small heads and large abdomens, they look a bit Shmoo-ish.

So many mouths to feed – what do they eat?

Plant juice. Lots and lots of plant juice. The majority of aphids are picky eaters who are attracted to a particular plant species or family. Aphids stick their little beaks into a plant’s soft tissues and start drinking. Entertaining a few aphids won’t compromise a plant, but hosting a whole battalion can damage the plant or impair the production of seeds. As an aphid feeds on plant sap, it excretes the unneeded portion in the form of small drops of honeydew which, according to Donald W. Stokes in A Guide to Observing Insect Lives, it normally flicks off of its abdomen. Wasps, butterflies and flies feed on the droplets that fall on nearby leaves.

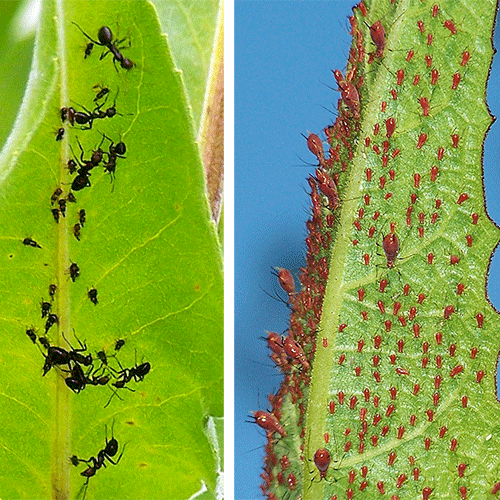

Some species of ants “farm” aphids, protect their chosen flock of aphids by chasing away enemies like ladybugs and lacewings, and carry the aphids to new feeding areas. They “milk” them by stroking the aphid’s abdomen, which results in the aphids giving off a drop of honeydew for the ants to ingest. Stokes says that aphids that are farmed hang onto their honeydew longer and so produce larger droplets when they are milked, and that the farmed aphids produce more offspring. Ecological relationships that benefit both parties are called “symbiosis.” The BugLady sees these interactions on her highbush cranberry bush in mid-summer and on burdock in late summer; sometimes the ants will make so many trips to the aphid-bearing plant that they will wear a trail on the ground.

How do Big Aphids make Little Aphids?

Aphids practice “Simple” or “Incomplete” metamorphosis—the young pop out, without benefit of eggs in the case of aphids, resembling their old lady, needing only to grow a few parts to look like adults. They reproduce by parthenogenesis (pronounced “virgin birth”), which means that Ms. Aphid doesn’t need Mr. Aphid to manufacture Baby Aphid. They reproduce in that fashion all summer, sometimes cranking out a few winged females that fly to nearby plants to produce more wingless females. It is said that a female aphid who starts walking up the stem of a plant will be a great-grandmother by the time she reaches the top (notice the different sizes of aphids in these pictures and see if you can spot a birth in progress).

The uniform, circular holes in the empty aphids were not produced by the mechanics of molting, as aphids popped out of their old skins and flew happily away; they are the work of parasitic wasps with a full stomachs.

At some time in August through October (exactly when depends on the species of aphid), both male and female offspring are produced. These exchange bodily fluids, and the female lays the eggs that will overwinter and produce another generation of females in spring. The BugLady assumes that any piano-moving must wait until fall (a little Gertrude Stein joke, there).

The BugLady is searching for an adjective to refer to the slightly unsettling, dense, masses of soft-bodied aphids she sees on milkweed pods. Maybe “seething,” if “seething” can refer to insects that are pretty much standing still. Perhaps a BugFan come up with a good collective noun, like “an ooze of aphids?” “A crust of aphids?”

Bonus points for identifying the plant the red aphids are on.

Happy Trails to You,

The BugLady