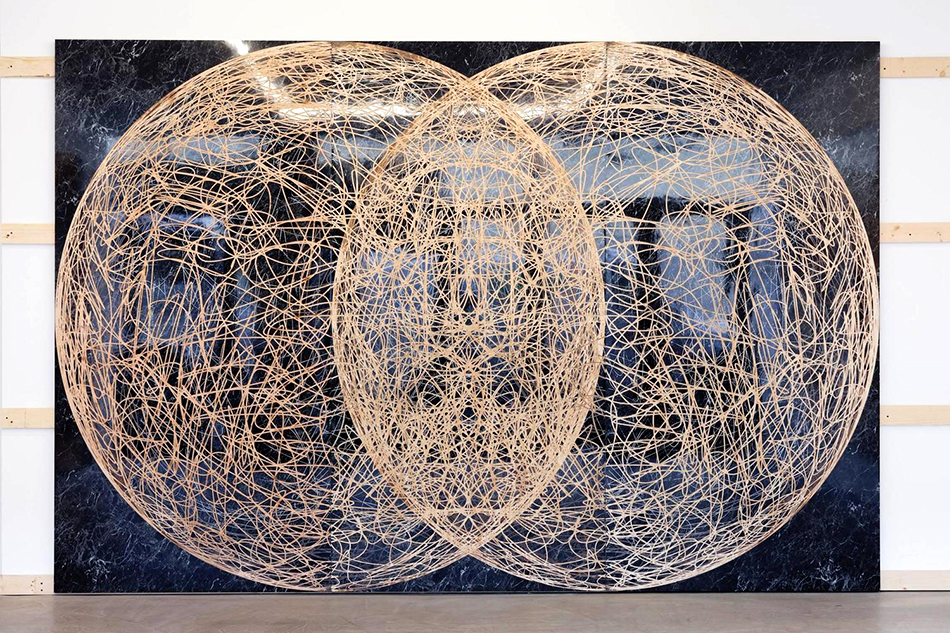

December 7, 2015Michael DeLucia is not the first in his family to be interested in reproducing the image of objects; his father worked at Kodak (photo by Christopher Martinez). Top: DeLucia‘s new installation “Appearance Preserving Simplification,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, is made from veneered plywood panels that mimic luxe materials with intricate patterns carved in them (photo by Wayne McCall, courtesy of the artist).

Michael DeLucia likes to compare his wall reliefs to crop circles — those mysterious patterns impressed in fields that attest to the reality of intangible objects (whether imposed by natural, supernatural, extraterrestrial or man-made forces). As a classically trained sculptor who is now fluent in the virtual space of the computer, DeLucia models three-dimensional objects onscreen and, using a computer numerical controlled (CNC) router, carves grooves into the one-inch-thick surfaces of four-by-eight-foot laminated plywood panels to create the illusion of geometric volumes or of household objects emerging at a grand scale. Confounding and mirage-like, the results produce a dynamic tension between image and material, between two and three dimensions.

For his new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (on view through February 21), DeLucia made panels that he used to remodel the museum’s reception desk and an adjacent gallery space into a corporate-style waiting room. Projecting from the faux-luxurious veneers, densely installed from floor to ceiling, are ghostly images of the kinds of objects one would find in such a reception area — seating, a fish tank, a potted plant — but overlapping one another and out of sync with the actual architecture and scale of the space.

“What is an object in the context of this digital media that’s really pervasive now, and how does that affect sculpture?” the artist asks, rhetorically, while sitting in the office area of his studio in Queens, New York. These are among the fundamental issues addressed in his sculptures at the Santa Barbara museum and his work in general. Referring to the image of a table lamp on his computer screen that he had downloaded from a Crate & Barrel webpage, then modified using CAD software, he says, “I think of this as the object itself, and I think of the panel as the space where an impression of the object is left.”

In the large workshop adjacent to his office, he demonstrates how the noisy CNC router “draws” the same lamp with a mechanical spindle that digs lines through the granite veneer of the panel. The deeper the spindle sinks into the plywood beneath the laminate, the brighter the pathways that are created and the more the contours of the lamp appear to project forward.

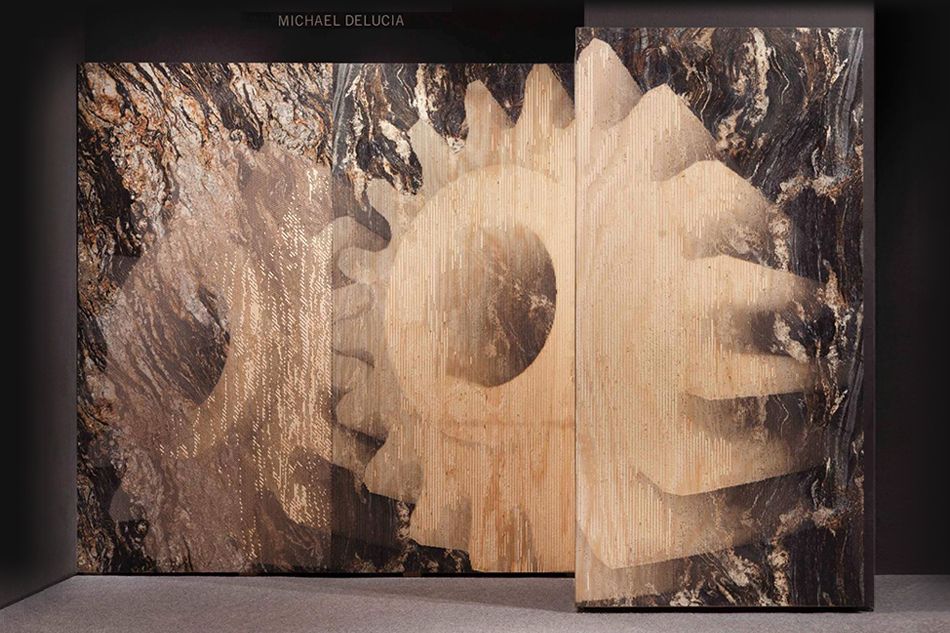

Man Machine, 2015

DeLucia is interested conceptually in how the computer software separates form and material — the opposite of how a traditional sculptor would choose a material out of which to model an object. He explains that after he defines a form onscreen, he can apply any material to it, even an orange peel if he wanted, like a swatch. He likes working with standardized sheets of decorative Formica veneers that ape fancy stone and wood grains, drawn by their nostalgic qualities. “We’ve all been in a hotel lobby or elevator with these veneers,” he says, going through his inventory of works done on trompe l’oeil panels resembling walnut, travertine, marble, agate and jade. “My friend’s mom had countertops like this green material here.” He also associates them with cave walls and views his reliefs as shadows of the “real” digital images, à la Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.”

DeLucia was born in 1978 in Rochester, New York, where his father worked for Kodak. He studied sculpture as an undergraduate at the Rhode Island School of Design, becoming proficient in the old-fashioned shop techniques of woodworking, welding, casting and mold making. He spent his senior year in Italy apprenticed to a stone carver in Pietrasanta and, after graduating in 2001, went to work for Jeff Koons making molds and detailing castings. This sparked his interest in finely crafted figurative sculptures, which he pursued in graduate school at the Royal College of Art in London. In his third term there, he had to give up his studio (for the installation of that year’s degree exhibition) and, to compensate for the lack of work space, became proficient in 3-D-modeling software. “It just became my medium,” says DeLucia, who received his degree in 2004 and moved to New York two years later.

Early on, he made sculptures of quotidian items — mops, garbage cans, fire hydrants — that were translations of his onscreen experiences with the objects. Using plaster, for instance, he molded a pristine doppelgänger of a banged-up washing machine and exhibited the two objects back-to-back, as mirror images. He also milled a series of Styrofoam objects at Digital Atelier, a New Jersey company that makes huge CNC machines available to sculptors, but then he became interested in laminated-plywood sheets as a way to work through his ideas more quickly and at lower cost.

Gorilla in the Mist, 2014

DeLucia first experimented with compressing basic three-dimensional abstract forms — spheres, cubes, cylinders — into shallow reliefs. He showed the results of these experiments in 2013 at Eleven Rivington in New York, where he will have another exhibition this spring. Last year, for a show at Anthony Meier Fine Arts in San Francisco, DeLucia drew inspiration from the former domestic life of the 1911 mansion the gallery occupies. He used his technique to refill the space with reliefs of home furnishings: an aquarium, a television, an easy chair and a variety of table lamps whose images he’d downloaded from stock-model websites.

“Some look like high modernism, but mixed with a craft application of those ideas, some look Egyptian — but they all boil down to the basic geometric properties that I liked about the minimal forms,” says DeLucia. The more complicated objects that he now works with can cause errors or unexpected incidents between the router and the material. “I don’t exactly know how the detail in them will affect the material, how it’s going to warp and bend and splinter,” he says. “The wood grain is quite visual and sometimes supersedes the recognition of the object.”

The artist’s first monograph, simply titled Michael DeLucia, will be released by Black Dog Publishing early next year, in tandem with the Santa Barbara show. “I’m trying to inject an unexpected abstraction into a familiar space to give you a surprising experience,” DeLucia says of the new reception area he created in the museum. His sheets of wide-plank black-walnut veneer mimic the texture of the real thing convincingly, “but every sheet is exactly the same,” he adds. “When you see a full room of them, you’ll register that something fake is going on. As a sculptor, I’m interested in the nostalgia we have for what we think of as valuable materials.”