The morning is bathed in hazy twilight as the "Rolling Swiss 2" leaves the harbour of Florø and turns south off the rocks of Stabben Fyr. A beefy oil rig supply vessel, lame on the towing wire of an ocean-going tug, creeps towards the lighthouse from the open sea. The wind is still light and should clear up a little, but the next front is approaching and should reach the coast within the next twenty-four hours.

The highlight of our trip

Half shielded by large and small islands, we head south, through the Rekstafjord, the Brufjord and between Askrova and Svanøy. We criss-cross the sharp crevices in the rocky ridge of the rising coastal mountains. We encounter a few Norwegian motorboats, coastal freighters with Nordic names and the fast ferries, which plough straight through the grey sea according to a precise schedule. At the Trætanes beacon, whose house is even marked with a vertical red stripe, a Swedish sailor on the opposite course returns our greeting.

His gaze briefly lingers on the red flag with the white cross waving from the stern of our Trader 42 to port, not an everyday sight in these latitudes. The "Rolling Swiss 2", on which we are exploring the west coast of Norway for a fortnight this summer, belongs to the Cruising Club of Switzerland. We boarded the ship in Ålesund a few days ago and have round the infamous Vestkapp on the Stadlandet peninsula (see BOOTE 2/2014). Before the cruise comes to an end for our crew of five in Bergen and the yacht is handed over to the next crew, the real highlight still lies ahead of us - the mighty Sognefjord.

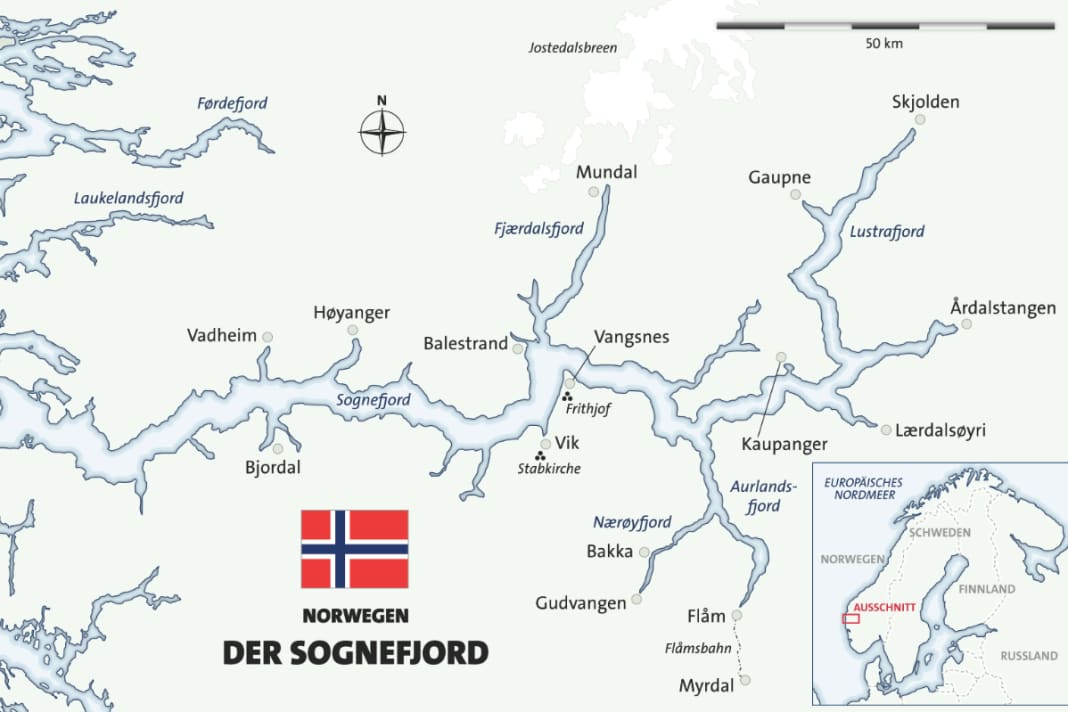

It cuts more than 200 kilometres deep into the land, making it not only the longest estuary in Europe, but also the longest inhabited fjord in the world, surpassed only by Scoresbysund in the icy, inaccessible east of Greenland. If you add the side arms that branch off to either side like the branches of a tree, the length is 370 kilometres. We have one week.

Almost 1300 metres under the keel

The sun comes out once again in Granesund, albeit hesitantly. It is her farewell greeting, even if we can't know that at this point. Soon we will feel like we are in Niflheim, that frosty realm of fog from the Nordic legends. But that won't detract from the mystical power of the Sognefjord - in fact, the opposite is true ...

Krakhellesund brings us from the north to the Sognefjord, which is around five kilometres wide at this point, close to its mouth in the Norwegian Sea. The "Rolling Swiss 2" now turns its bow inland. The wind comes from astern, from the open sea, and soon pushes us with a considerable wave. The spray is torn from the whitecaps as if by a fan and crashes against the back wall of the cake stand - the jet effect! There are almost 1300 metres below us, so it's no wonder that the echo sounder can't keep up.

Tiny and lost, a cruise ship pushes its way through the alpine panorama. Half-obscured by grey veils, snow fields shimmer high up on the flanks of the mountains, massive clouds roll along their slopes.

Dragon gable in the dark

We reach Vik, which lies on the southern shore of a small bay, at around 9 pm. We have already travelled around 90 kilometres on the Sognefjord to get here. We moor at the new wooden jetty in front of the souvenir shop, a private facility, as we soon learn. But for 200 Norwegian kroner we are still allowed to stay overnight. The shadows are already spreading in the valley, but we still want to walk a few more steps. So we head up through the village to the stave church of Hopperstad, which stretches its carved dragon gables into the darkness. The wooden church is one of the oldest of its kind in Norway and is said to date back to 1130.

The secret behind the black colour of the stavkirke is revealed to us the next morning by Markus, a German who ended up here and "just stayed", as he says. "The substance was invented many centuries ago," he explains. "It's a type of resin that comes from the root of the pine tree and has to be stored for seven years before it can be applied to the wet wood." The Vikings would also have used the coating for their clinker-built longships - "as an antifouling that lasts for a hundred years."

Children swim in a wetsuit

Under a ragged sky, the "Rolling Swiss 2" pushes further up the fjord accompanied by five Beaufort. Where the Fjærlandsfjord branches off to the north, large ferries shuttle between the towns of Balestrand and Vangsnes. From the southern shore, Frithjof, an old Norse hero, watches over the water with a stern gaze. The colossal figure towers 22 metres high, a gift from Kaiser Wilhelm II. The passionate Norway fan travelled to the unveiling himself in 1913: "We are all Teutons," he called out to the invited guests alongside the Norwegian King Haakon VII. It was reported that the applause was very good and the emperor's sailors gave three thunderous "hurrahs".

Three hours later, we are moored at the guest jetty in the sheltered bay of Kaupanger, a municipality on the northern shore of the fjord. Next door, children in wetsuits are swimming. It may be August, but Nordland remains Nordland! Kaupanger also boasts a stave church, although the first building on this site was burnt down along with the town in the Middle Ages: the inhabitants didn't like the news delivered by a royal messenger. Without further ado, the courier was beaten to death - but the punishment was swift to follow.

Reverends feel disturbed

The Sogn Fjord Museum right next to the jetty, on the other hand, tells the story of the boat as a means of communication and transport when there were no roads along the fjord and the settlements could only be reached by water. This also includes the story of a priest who always had six men row him to church - seven hours there, seven back. He read from the Bible the whole time. You can understand why the pious boatmen were doubly pleased when a motor was finally installed in the boat. But they rejoiced too soon: the rattling of the single cylinder disturbed the cleric as he read aloud - and so they went back to rowing.

The slender sognabåt also played an important role in the early days of fishing tourism: around 1850, English aristocrats who spent their summer holidays in Norway introduced salmon fishing. Again, the peasants were allowed to row "high lords" through the area - but this time at least for good money.

Lots of traffic in Flåm

Fine, cold rain falls the next day. The entrance to the Aurlandsfjord becomes visible through the windscreen wipers. Flåm, at the end of its almost thirty kilometres, is our destination for the day. We are registered, a must with the few guest berths in the small harbour. The small harbour is a magnet for visitors and a traffic hub. Three cruise ships crowd the narrow bay. While the two smaller ones lie in the roadstead, the 300 metre long "Costa Luminosa" sits like a cork on a bottle: from the 150 metre pier, it protrudes so far into the harbour entrance that only a narrow passage remains. Tender boats, ferries and excursion boats round the towering stern of the giant every minute. At just the right moment, we also slip through. The harbour master greets us with a handshake.

Flåm is a bit of Disneyland in the Norwegian solitude. The "settlement" is almost completely new, from the only supermarket (a "goldmine") to the woollen sweater shops and the Ægir bryggeri with its spherical sounds in the stylish, rustic taproom and the polished brewing kettles. The interior of the microbrewery would certainly have impressed even seasoned Viking legends such as Erik Blutaxt and Halvdan Svarte, but at the price of 90 kroner (just under 11 euros) for half a litre of Bøyla Ale, they would probably have sharpened their blades ...

On the "roof" of the Sognefjord

The Flåmsbana railway station is a noisy jumble of languages. Guides with number plates stride through the crowd like army commanders, their pennants fluttering on the poles behind them: France, Germany, China. The brightly coloured, oversized rucksacks of the occasional backpacker shine like navigation marks in the surging crowd.

The one-hour journey on the Flåm Railway up to Myrdal, where there is a connection to the Bergen Railway, is a must. With one locomotive in front and one behind, the single-track standard gauge railway climbs up to the subarctic high plateau. On the way: steep gradients, tight hairpin bends, waterfalls and tunnels. But the spectacular views are not on the cards; the tickets costing 400 crowns per person turn out to be a poor investment in the rain and fog. We could even have got four beers in the brewery for that, plus a tip ...

Noise protection in the Nærøyfjord

In the morning, it is only a comparatively short hop across to the Nærøyfjord, which branches off to the west halfway along the Aurlandsfjord. Although it measures 18 kilometres, it is very narrow - barely 250 metres at its narrowest point. At the same time, the rock faces on both sides tower upwards. The highest ridge measures 1760 metres, and the echo reverberates loudly off the stone walls. The ship's horn must not be used here - the sound could trigger rock avalanches.

Since 2005, the Nærøyfjord, together with the better-known Geiranger, has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and rightly so: we drive as close as we can to a waterfall. At the very top, the water seems to tumble out of the clouds, flowing or running down the furrowed rock in countless white veins. It is steep, but not too steep for the goats, tiny, bright spots in almost impossible places on the vertical wall.

In the early afternoon, we reach Bakka on the west bank, a small village with two dozen houses huddled against the green slopes and a white-painted church. Its large, cast-iron stove under the organ loft is designed for long, cold winter days. A remote area. In the past, only the Rindalsstieg, now also a UNESCO heritage site, led up to the alpine farms and further into the outside world; an arduous climb after the Sunday church service.

With the Vikings of Gudvangen

The same evening in Gudvangen at the end of the fjord is all about other gods: around the crackling campfire, Runar the skald tells of the age of the Aesir, of the sea god Aegir, who is supposed to brew beer for the table of the gods and feels so hurt in his pride that he denatures the contents of the golden cauldron. Or of Heimdall the Guardian, who always fortified himself with a potion of black earth and salt water - and pig's blood. And when he pulls the little bone figures out of his wide cloak and whirls them around, accompanied by his deep chanting, you can actually see Thor fighting with the Midgard Serpent in the flames.

Runar's real name is Daniel and he works for a shipping company in Oslo, but he comes to Gudvangen once a year, always at the end of July for the big Viking festival. A whole village of tents is erected and in the evening, when the last day tourists have left, people live and laugh and argue as they did a thousand years ago. As we chase the dinghy across the quiet fjord back to Bakka, we can still see the red glow of the fire for a long time.

Off to the freezer!

We head north one last time, past Leikanger and Vangsnes and into the Fjærlandsfjord. It's getting colder, but that's no wonder - no arm of the sea leads closer to the icy carapace of the Jostedalsbreen, Europe's largest glacier. Mist and sea smoke lie over the now almost still water, which is coloured a milky green by the sediment of the glacial streams. A kayak glides silently past us. And then the houses of Mundal emerge like shadows from the white void. It is only a few kilometres by bus from here up to the Jostedalsbreen.

As early as 1880, when the Swedish King Oskar II visited Mundal (Norway was still part of the neighbouring country at the time), people were making a good living from tourism. The monarch also asked to be transported to the glacier and wanted to pay for it. But the proud inhabitants declined with thanks. "Then give it to the needy," he said. "There are none here," was the reply. - 100 years later, the then US Vice President Walter Mondale, whose ancestors came from Mundal, flew in. Apparently he knew the story of King Oskar and is said to have brought 300 bottles of bourbon with him. This gift was gladly accepted ...

If, like us, the clouds don't allow a view of the eternal ice, there is still no chance of boredom. Mundal is a "book village": millions of second-hand books are lined up on covered shelves right by the street or stacked up in the twelve second-hand bookshops. That's how we stumble into Jan-Peter's colourful shed, which specialises in comics. We talk about our journey, which will come to an end in Bergen in two days' time. "It's quite simple," he says with a bearded grin. "If you liked it, then you have to come back!"

-----

BACKGROUND

The Cruising Club of Switzerland

The motor yacht "Rolling Swiss II", with which we travelled on this trip, belongs to the Cruising Club of Switzerland (CCS) and is used for training and travelling cruises. The sailing areas change from season to season in order to be able to offer a varied and attractive programme. This year, the 13.30 metre Trader 42 is heading for the English Channel and Brittany. The seaworthy semi-glider is technically state-of-the-art. Three cabins offer space for a total of six crew members. The motorboat department forms an important division of its own within the club, which is one of the largest in Switzerland with around 6500 members and is a leader in the field of deep-sea training in recreational boating. www.ccs-motorboot.ch