Watch CNN’s new Original Series “The Movies” to explore the political and cultural shifts that have shaped American cinema starting Sunday, July 7 at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

When Tim Burton’s “Batman” debuted in theaters 30 years ago in 1989, it didn’t just kick off a major, still-flourishing movie franchise and the current era of superhero-led blockbusters. The film also had a profound impact on Batman himself, and the way comic book creators would depict the character over the next three decades.

“It catapulted Batman to the top of everyone’s favorite superhero franchises, and he’s been there ever since,” remembers Jim Lee, who was a 25-year-old emerging comic book artist when the film bowed and would to go on to become one of the definitive Batman artists and the co-publisher of the Dark Knight’s print home base, DC Comics.

“The movie was instrumental in really bringing to the wider masses the concept of Batman,” says Lee. “He’d always been a favorite among comic book readers, and people remembered very fondly the TV show. But what Tim Burton did was really take it to a different level, made it more serious and baroque and romantic and creepy – so many elements he added to it.”

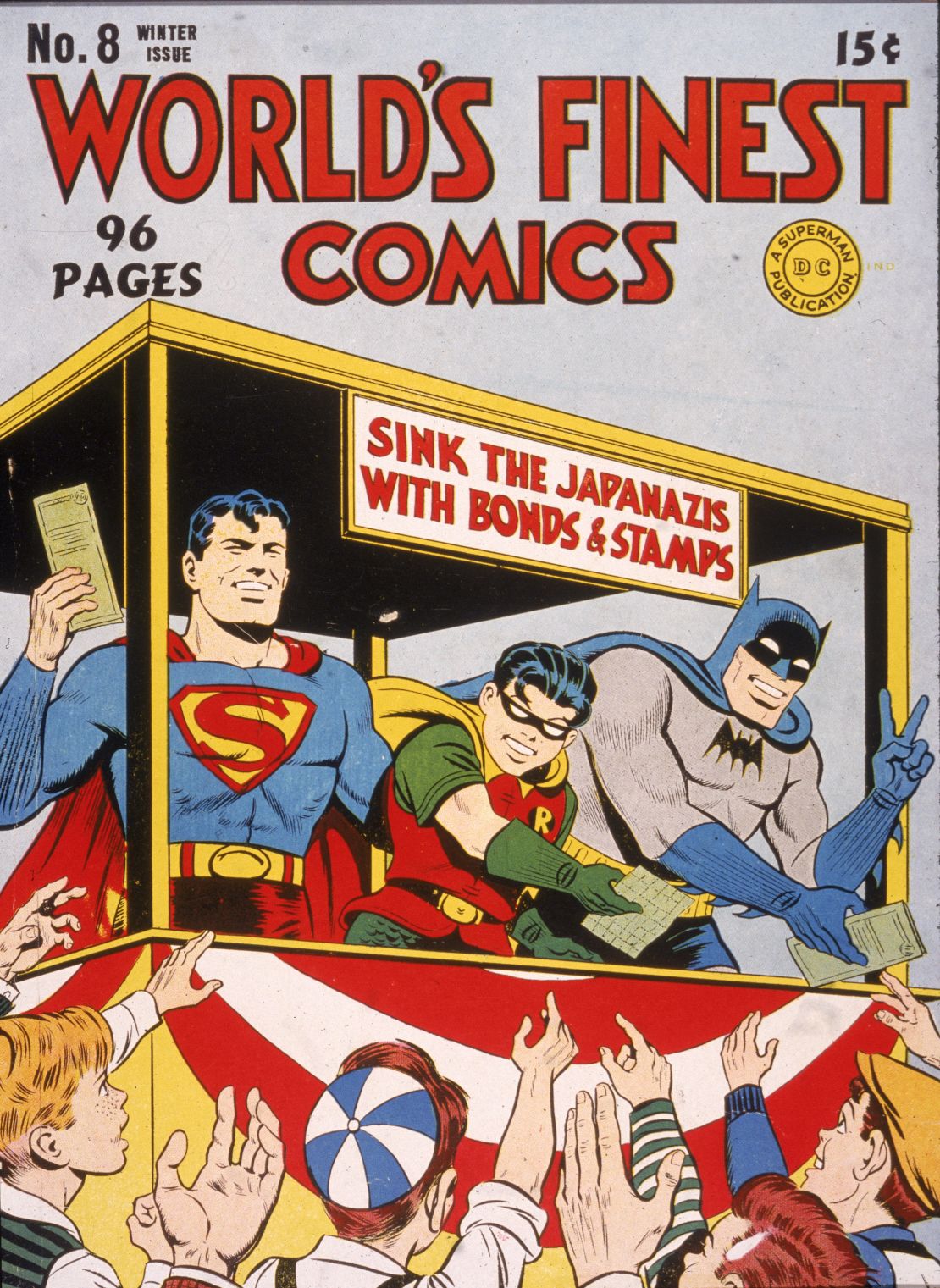

Launched in 1939 in the superheroic spirit of Superman, DC’s smash success from the previous year, but with a healthy dose of noir, Batman had over time veered away from the pulpier, broodier roots laid out by creators Bob Kane and Bill Finger – even the briefly uber-popular “Batman” TV series of the late ’60s starring Adam West, with its winking, campy take on the character, was only a few post-modern degrees away from the comics of the day.

The show made a ubiquitous pop icon of Batman, but by the early ’70s, in response the series’ fast slide from glory, creators like influential disruptor duo of writer Dennis O’Neil and artist Neal Adams had returned Bruce Wayne to a more moody, urban aesthetic that satisfied maturing readers, if not always sparking huge sales spikes. But ‘80s-era creators like Frank Miller, David Mazzuchelli, Alan Moore and Grant Morrison infused even more psychological complexity into the character, setting the stage for Burton’s “Batman,” which would forever shift mainstream perception of the character and leave its mark on the comics as well.

“As a character, he’d never been bigger,” says DC Comics co-publisher Dan Didio, who grew up in the heyday of the Adam West series. He credits the dichotomy of Burton’s sometimes spooky, sometimes loopy approach for subverting expectations and making an impact on both his generation as a new breed of fans. “To see that character grow up and mature along with me, and to approach it in a way that captures everything that’s great about the comic book character but with a maturation I know spoke directly to me at the time really sent me over the top.”

The comics were quick to seize on key aspects of the film, particularly in terms of Gotham City as a hellishly imposing urban war zone.

“You really saw [production designer] Anton Furst’s designs start taking hold, and the city becoming more baroque and more unique looking,” says Lee. “Before it was often represented as a worse version of New York City…The movie itself really made Gotham City stand out, and it really become another character in the mythology itself.”

“We’ve always tried to give Gotham City a personality and a certain level of darkness to explain why Batman patrols these streets,” adds Didio. “Ultimately that’s really what played well with so many creators, in the sense that it’s a city that’s totally shadows and gothic buildings and gargoyles. Burton’s film brought all of that fully in front of us, and that really has been the interpretation of Gotham City from that point forward.”

Costume designer Bob Ringwood’s sleek, black armored Batsuit also inspired new takes on the longstanding gray-and-blue/black spandex look. “A lot of artists were transfixed by the costume design,” says Lee. “You saw the blue trunks go away briefly at DC because of the importance of the movie, and even the impact of the Catwoman costume [in ‘Batman Returns’]. There are a lot of visual elements that made an impact on a generation of artists.”

But perhaps the ’89 film’s most profound contribution to comics was in its distinctive presentation of its villains. “For me it’s the creepiness of the mythology,” says Lee. “When you see it on paper, it’s one thing, but in Jack Nicholson’s performance as The Joker, and [Danny DeVito’s] Penguin, and even Michelle Pfeiffer as Catwoman, there was a weird, kind of horrific, creepy element to their portrayal of these villains…It really highlighted how sinister and edgy and off-center some of these rogues are. That’s an influence that’s still being depicted in the comic books and other adaptations today.”

And given that DC has routinely experienced publishing success with projects derived specifically from depictions of the Dark Knight in other media, including comics based on the 1966 TV show, “Batman: The Animated Series” and the “Batman: Arkham Asylum” video games, it’s possible that the Burton-verse Batman may emerge from the shadows in print someday, the publishers agree.

“We still get pitches today from creators who say ‘Hey, this was the property that made me a comic book fan? Can we do a comic book that ties directly into this particular reality as presented on the big screen?’” says Lee.