Experimental evidence for the hydrothermal formation of native sulfur by synproportionation

- 1MARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- 2Faculty of Geoscience, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- 3Institut für Geologie und Paläontologie, WWU Münster, Münster, Germany

- 4State Key Laboratory of Fluid Power and Mechatronic Systems, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Elemental sulfur (S0) is known to form in submarine acid-sulfate vents by disproportionation of magmatic SO2. S0 formed upon disproportionation shows δ34SS values considerably lower than the influxing magmatic SO2, which results in δ34SS values typically <0‰. The peculiar occurrence of isotopically heavy sulfur in the Kemp Caldera hydrothermal system (δ34SS > 5‰) and Niua North (δ34SS = 3.1‰) led to the suggestion that disproportionation is not the only sulfur forming process in submarine hydrothermal systems. We conducted hydrothermal experiments to investigate if synproportionation of SO2 and H2S can explain the occurrence and isotopic composition of S0 observed in some vent fields. Provided that SO2 and H2S are both abundant, this formation mechanism is thermodynamically conceivable, but it has not yet been demonstrated experimentally that this process actually takes place in submarine hydrothermal systems. We conducted the experiments in collapsible Ti-cells under pT-conditions (20–30 MPa, 220°C) that are relevant to S0 formation in submarine hydrothermal systems. We used starting concentrations of 10 mM sulfite and 20 mM sulfide of known isotopic composition. Under acidic conditions (pH25 °C = 1.2), S0 was the most abundant reaction product, but small amounts of sulfate were also produced. A Rayleigh fractionation model was applied to determine the isotopic composition of SO42–, SO2, H2S and S0 expected to form by SO2 disproportionation, H2S oxidation, and SO2–H2S synproportionation. The sulfur isotopic signatures of the sulfur produced in the experiments can only be explained by synproportionation of sulfite and sulfide. These results provide strong evidence that synproportionation is likely responsible for exceptionally high δ34SS values observed in S0 from some arc/back-arc hydrothermal environments, like the Kemp Caldera in the South Sandwich arc. Coeval degassing of H2S and SO2 is likely required to have this particular reaction dominate in the H–S–O reaction network and produce noticeable accumulations of isotopically heavy native sulfur at the seafloor.

1 Introduction

In general, hydrothermal systems in arc/back-arc settings are enriched in volatiles like H2O, CO2, SO2 and H2S as a result of magma degassing (Reeves et al., 2011; Seewald et al., 2015; Wallace et al., 2015; Seewald et al., 2019). Hydrogen sulfide is not necessarily a direct product of magma degassing, but can also form through reduction of seawater sulfate or sulfur leaching from the host volcanic rock (Shanks et al., 1981).

It is well established that SO2 is a major gaseous species in many arc magmas (e.g., Giggenbach, 1987; Fischer et al., 1998). Upon cooling and mixing with aqueous solutions in magmatic-hydrothermal systems, SO2 is expected to disproportionate to sulfuric acid as well as both H2S and elemental sulfur (see Eqs. 1, 2; Gamo et al., 1997; Kusakabe et al., 2000; Gena et al., 2006; Butterfield et al., 2011; de Ronde et al., 2011; Seewald et al., 2019):

The sulfuric acid dissociates and gives rise to low pH and high sulfate concentrations in vents that are affected by this process (common in acid-sulfate vents). The sulfate formed in these submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems by disproportionation reactions (1) and (2) has elevated δ34S values (between ca. 17 and 25‰; de Ronde et al., 2005; McDermott et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2021) relative to the influxing magmatic SO2 (4–10‰; Hannington et al., 2005). Elemental sulfur (S0) produced alongside sulfate can have very low δ34S values typically <0‰ like at the DESMOS caldera (δ34SS = −9.3‰; Gena et al., 2006) or at the Cone sites of Brothers volcano (δ34SS = −8.0‰; de Ronde et al., 2011). Likewise, dissolved sulfide and sulfide minerals in arc-hosted hydrothermal vent fluids typically show negative δ34S values (δ34S = −9.9 to −0.4‰), indicating SO2 disproportionation (cf. Herzig et al., 1998; de Ronde et al., 2005; Gena et al., 2006; de Ronde et al., 2011; McDermott et al., 2015).

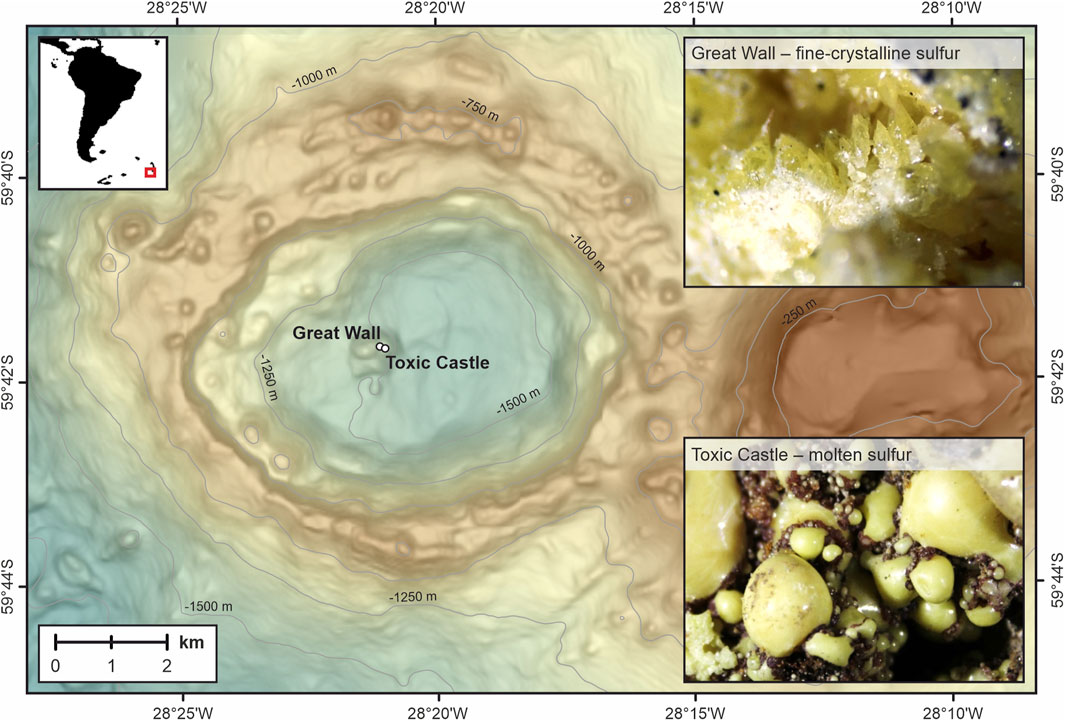

Although sulfides and elemental sulfur often have δ34S values <0‰, positive values for S0 have also been recently documented. In Niua North, an acid-sulfate vent in the northernmost Tonga arc, native sulfur exhibits a δ34S value of 3.1‰ (Peters et al., 2021). In the Kemp Caldera of the South Sandwich island arc in the Scotia Sea samples of S0 from acid-sulfate vent fields show even higher δ34S values ranging from 5.2 to 5.8‰ (Figure 1; Kürzinger et al., 2022).

FIGURE 1. Bathymetric map of the submarine Kemp Caldera, which is located at the southernmost tip of the intra-oceanic South Sandwich arc. Elemental sulfur was sampled at the active white smoker vent fields Great Wall and Toxic Castle in the caldera center during the R/V Polarstern PS119 expedition in 2019.

Peters et al. (2021) explained the large range of sulfur isotopic composition of sulfate, sulfide and native sulfur by variable SO2 flux, disproportionation conditions, and host rock compositions. Their SO2 disproportionation model for S0, however, cannot fully explain the δ34S value (3.1‰) of elemental sulfur at Niua North, unless the ingassing of an unusually 34S-enriched SO2 is assumed (Peters et al., 2021). The even higher δ34S values from Kemp Caldera were found in the hydrothermally active area in the center at the eastern flank of a resurgent cone represented by the white smoker vent fields “Great Wall” and “Toxic Castle” (Figure 1). There, fluid venting at low to intermediate temperatures (60 to ∼220°C) is associated with precipitation of elemental sulfur (Kürzinger et al., 2022). The molten S0 from Toxic Castle shows δ34S values between 5.2 and 5.5‰. An even higher value of 5.8‰ was measured at Great Wall from a fine-crystalline sulfur sample taken from the wall-like structure. These high δ34S values suggest that disproportionation of magmatic SO2 is unlikely the source of elemental sulfur at these sites. Oxidation of H2S, proposed as a mechanism to explain 34S-enriched elemental sulfur in terrestrial geothermal sites (Kleine et al., 2021) is implausible for submarine vent sites (Kürzinger et al., 2022).

Kürzinger et al. (2022) suggested synproportionation of SO2 and H2S to S0 and water as an alternative to explain the observed high δ34S values of the S0:

It had been previously suggested that this synproportionation reaction is potentially a major sulfur forming mechanism of low-temperature fumaroles and solfataras in subaerial hydrothermal systems (Mizutani and Sugiura, 1966; Giggenbach, 1987; Chiodini et al., 1993). The elemental sulfur there is formed over a temperature range from <95 to >119°C (Mizutani and Sugiura, 1966). It was also hypothesized to play a role in the formation of liquid sulfur lakes in submarine volcanoes of intra-oceanic volcanic arcs, where the flux of magmatic volatiles is high (e.g., de Ronde et al., 2015). However, most accumulations of elemental sulfur at the seafloor have been explained by a high degassing flux of SO2 followed by disproportionation to sulfur and sulfuric acid (Gamo et al., 1997; Butterfield et al., 2011; Seewald et al., 2015). This idea is corroborated by negative δ34S values of sulfur that are expected to result from the disproportionation pathway of sulfur formation (e.g., Gamo et al., 1997; de Ronde et al., 2011; McDermott et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2021).

The first time SO2–H2S synproportionation was discussed in connection with sulfur formation in submarine arc volcano-hosted hydrothermal systems was in Kürzinger et al. (2022), who showed that SO2–H2S synproportionation may be exergonic not only in subaerial but also in submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems that have high concentrations of SO2 and H2S. These authors also used a Rayleigh fractionation model to demonstrate that the isotopic composition of native sulfur from the Kemp Caldera, South Sandwich arc, is consistent with the synproportionation model. The synproportionation reaction of SO2 and H2S in aqueous solutions is expected to proceed much slower than in gas phase and it was unclear if the sulfur can form from within a single-phase aqueous solution or if sulfur condensed in a gas phase prior to dissolution of the gases in a hydrothermal solution.

To test the idea that elemental sulfur in submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems may form by synproportionation in an aqueous solution, we conducted autoclave experiments in which we reacted dissolved SO2 and H2S under elevated pT-conditions. Sulfur concentrations and δ34S values of reactants and reaction products were determined to discern plausible reaction pathways with respect to the fate of SO2 (disproportionation versus synproportionation). The energetics of reaction (3) is examined and Rayleigh fractionation models for three S0-forming reactions are presented. A reaction path model is introduced that explores which reactions contribute to the S0-formation and how the isotopic compositions of reactants and reaction products evolve on the way to equilibrium.

2 Methods

2.1 Experimental setup

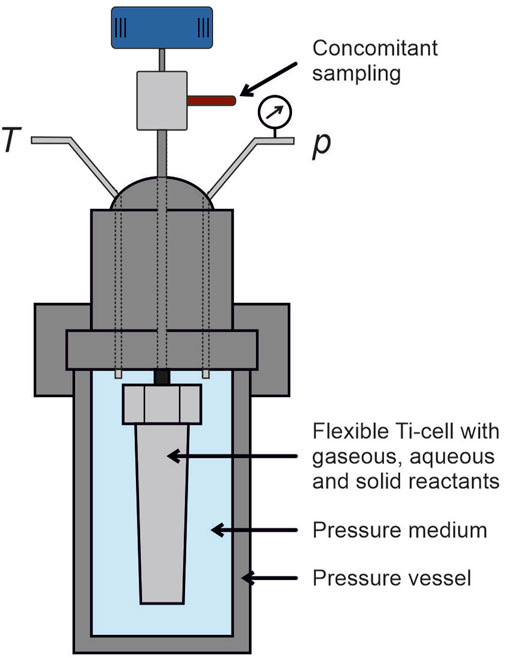

Three experiments were conducted using a modified Dickson-type experimental setup that allows simulations of in-situ hydrothermal environment conditions (Dickson et al., 1963; Seyfried et al., 1987). Reactants (fluids and solids) reside within a collapsible container, which is sealed and mounted into a stainless-steal pressure vessel filled with distilled water (see Figure 2). Pressure of the water reservoir and the temperature of the vessel can be controlled independently (up to 400°C and 56.5 MPa). As the pressure is isostatically transferred to the contents of the collapsible cell, fluid sampling is enabled through a titanium access tube (featuring an in-line 0.2 µm mesh Ti-filter) and an attached custom fitted Ti-valve. Due to the reactivity of gold in H2S-rich hydrothermal solutions we used a collapsible titanium foil cell (Vtot ∼ 60 mL) instead of the more widely used cells made of gold (Hayashi and Ohmoto, 1991; Wu et al., 2016). Prior to the experiments, the Ti-cells were thoroughly cleaned with hydrochloric acid and heated to 400°C in air to create a surface layer of titanium oxide that is sufficiently inert under the targeted experimental conditions.

FIGURE 2. Scheme of the used hydrothermal reactor. The Dickson-type experimental setup consists of a pressure vessel that allows independent pressure and temperature control featuring a flexible titanium reaction cell from fluid samples that can be dawn over an access tube and valve made of titanium.

All three experiments were designed to investigate the isotopic fractionation of SO2, H2S and S0, respectively, during the synproportionation reaction. The reactants sodium sulfide hydrate (Na2S · 3 H2O) and sodium sulfite (Na2SO3) were weighed and transferred into the titanium cell prefilled with ∼60 mL of O2-free ultrapure water (thoroughly purged with N2). The reactants were weight into the cell to set a 20 mmol/L sulfide and 10 mmol/L sulfite concentration within approximately 60 mL of fluid (see Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). The concentrations for sulfide and sulfite were chosen in the milli-molal range to reflect typical concentrations of dissolved sulfur gases in submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems (e.g., Butterfield et al., 2011; de Ronde et al., 2011; Seewald et al., 2015). The H2S:SO2 ratio of 2:1 is the same used by Mizutani and Sugiura (1966). A neglectable amount of elemental sulfur (between 0.9 and <2.5 mg) was added as seed crystals to prevent kinetic inhibition that can occur with homogenous nucleation.

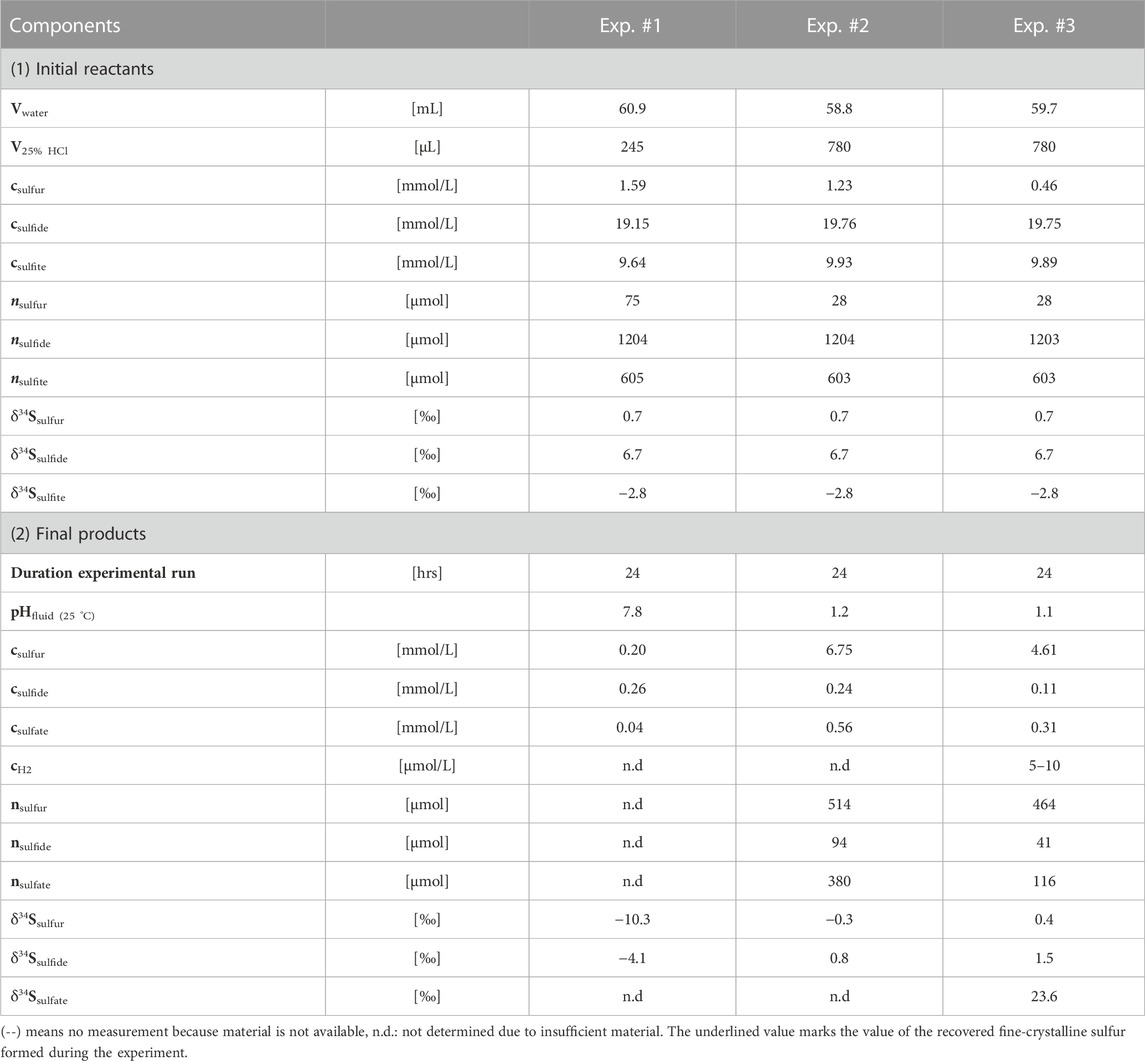

TABLE 1. Specifications on the conducted experiments including initial amount of water (Vwater) and hydrochloric acid (V25% HCl) as well as concentrations and sulfur isotopic characteristics of the initially introduced solid reactants (Na2S · 3 H2O, Na2SO3, S0) and the ultimately retrieved (solid) product phases (S0, SO4 as BaSO4, H2S as Ag2S, H2). The pH-values were determined in the equilibrated final solution.

Upon dissolution under hydrothermal conditions, these reactants provide the naturally occurring sulfide and sulfite for the experiments:

The OH− released by reaction (4) and (5) causes the starting solution to be highly alkaline, which prevents degassing of sulfide and sulfite. However, the natural hydrothermal fluids are acidic and the neutral species H2S and SO2 dominate. The pH was therefore adjusted to a pH of 1.2 by adding <1 mL of 25% HCl (see Supplementary Table S1) right before the Ti-foil cell was sealed within the pressure vessel.

Thus, the starting fluid had 60 mmol/L of both Na+ and Cl− dissolved. The setup was then heated to approximately 220°C for approximately 24 h, while the pressure was maintained between 20 and 30 MPa.

2.2 Sampling and sample treatment

For the characterization of S0, H2S and SO42–, 10 mL of sample were drawn from the reactor cell with a gastight syringe at experimental conditions after 24 h.

The samples were transferred into a vacuumed septum vial and 1 mL of 85% H3PO4 was added to enable a quantitative extraction of H2S by means of N2 purging (20 min) through a gas wash bottle prefilled with 20 mL of 5% AgNO3 solution. Sulfide precipitated as Ag2S flakes and was collected on a pre-weighed polycarbonate filter enabling a subsequent gravimetrical quantification. Next, 5 mL of the N2-purged, acidified solution were transferred to a second vacuumed vial and 300 µL of a 1M BaCl2 solution were added to precipitate any potentially present sulfate. In experiment #3, 600 µL of the 1M BaCl2 solution were just added to the 10 mL sample in order to maximize the sulfate yield for subsequent isotopic characterization. Total amount of dissolved sulfate previously precipitated as BaSO4 was subsequently derived by weight.

Concentrations and absolute contents for H2S, SO42– and S0 given in Table 1 were derived by extrapolating the amounts retrieved from the respective sample volumes to the total fluid volume for each experiment.

An additional 1.75 mL of fluid were sampled into a gas tight syringe for the quantification of potentially formed H2. Hydrogen was then quantified from about 0.25 mL gaseous headspace that unmixed from the fluid upon depressurization using an Agilent 7820 A gas chromatograph equipped with a 60/80 Molsieve column and a thermal conductivity detector.

2.3 Sulfur isotope measurements and computational methods

For sulfur isotope measurements, ca. 50 μg of elemental sulfur or 300–400 µg of silver sulfide are mixed with 400–800 µg of V2O5 and homogenized within a tin cup. Isotope measurements were carried out via elemental analyzer isotope ratio mass spectrometry (EA-IRMS) using a Flash EA IsoLink attached to a Thermo Fisher Scientific Delta V Advantage mass spectrometer. The reproducibility determined by replicate measurements was usually better than 0.3‰ (1σ). Analytical performance was controlled with IAEA-S1, -S2, -S3 and NBS 127 as international reference materials and with laboratory internal standards.

Using the initial isotopic composition of the reactants, we constructed a Rayleigh fractionation model (cf. McDermott et al., 2015; Kleine et al., 2021; Kürzinger et al., 2022). With this fractionation model we were able to predict sulfur isotopic compositions for all potential formation pathways and classify the measured values accordingly. Further details of the calculations are given in the Supplementary Material. Note: The isotopic composition of the reactants does not reflect the isotopic composition of naturally occurring sulfur species in magmatic-hydrothermal systems. Thus, the experimental isotope values will not mirror those measured in natural samples, but the magnitude and direction of isotope fractionation between the different sulfur species at given pT-conditions will be comparable.

Gibbs energies of reaction under experimental conditions were calculated for the sulfur formation reactions (syn- and disproportionation) as well as for the dissociation reactions of all involved sulfur species using the SUPCRT92 code (Johnson et al., 1992). The reaction path computation with Geochemist’s Workbench (v. 12) makes use of a tailor-made database constructed for 25 MPa using SUPCRT92 and the OBIGT database (Dick, 2019). Equilibrium constants of all possible redox reactions (see Supplementary Figure S1) involving the four species H2S, S0, SO2 and HSO4− are included in the database. These were derived essentially from prior experimental studies of sulfur hydrolysis and redox reactions (e.g., Ellis and Giggenbach, 1971).

The model is not a traditional titration path but instead it has the full amounts of SO2 and H2S in the system initially. All possible redox reactions are then kinetically inhibited to the same extent to investigate how the reaction network is predicted to evolve as the system approaches equilibrium state.

3 Results

3.1 Experimental results

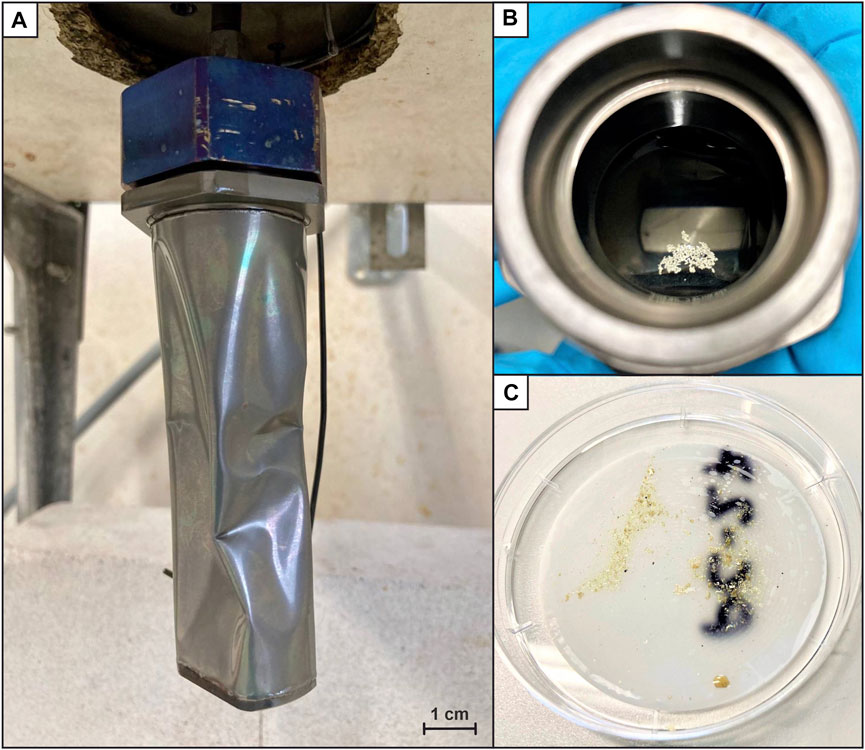

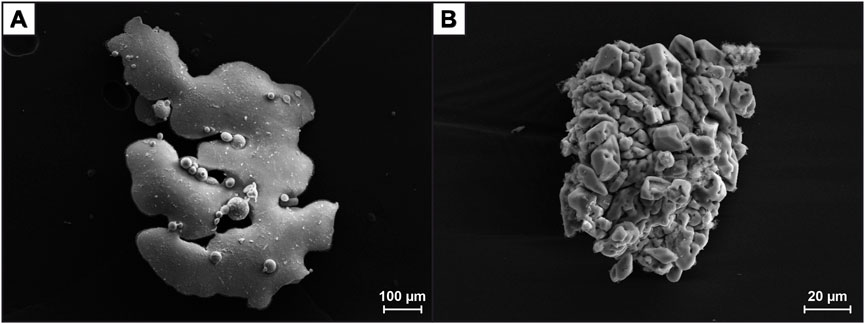

Photographs of the experimental results as well as representative SEM images of elemental sulfur formed during the experiments are shown in Figures 3, 4.

FIGURE 3. Images of the titanium reaction cell and the elemental sulfur formed during the last experiment. (A) Collapsed titanium cell after termination of the experiment, (B) View into the open cell: Elemental sulfur floating at the surface of the solution; additional sulfur quantities were found on the Ti-cell wall and bottom, and (C) Same fine-crystalline elemental sulfur as described in (B), recovered on a polycarbonate filter.

FIGURE 4. SEM images of elemental sulfur formed during experiment #2. (A) Sulfur particle from the subsample taken at 220°C. The appearance is similar to the molten sulfur at Toxic Castle (Kemp Caldera), and (B) Fine-crystalline sulfur recovered from the Ti reaction cell after finishing the experiment (cf. Figures 3B, C). These particles resemble sulfur from the Great Wall site in Kemp Caldera (cf. Figure 1).

For each experimental run, the individual steps were carried out as described above. During the first experiment (#1), precipitation of sulfur was not observed, although H2S clearly had formed (strong characteristic smell) and the solution acquired a yellowish color. Sulfur precipitation only occurred following acidification with phosphoric acid for H2S expulsion. Apparently, the synproportionation reaction does not proceed under alkaline conditions or kinetics are too sluggish for significant reaction turnover (previous pH ∼ 7.8, see Table 1).

Accordingly, the follow-up experiments (#2 and #3) were run at conditions energetically more favorable for the synproportionation reaction we suspect to take place at Toxic Castle in the Kemp Caldera hydrothermal system. The pH at Toxic Castle is likely lower than measured in 2019 (pH25°C = 5.7) due to seawater entrainment during sampling (see Kürzinger et al. (2022) for details). We hence adjusted the starting pH25 °C to 2 in experiments #2 and #3, and native sulfur did form under these acidic conditions. Abundant fine-crystalline sulfur could then be recovered from the open titanium cell after terminating both experiments (Figure 3). Small sulfur flakes were visible even in the fluid sample extracted prior to the termination of the experiment, indicating that the sulfur did not form during cooling. Sulfate, only present in dissolved form, could be precipitated as BaSO4 for a subsequent quantification (0.3–0.6 mmol/L). In addition, small amounts of H2 could be quantified (5–10 μmol/L).

The sulfur recovered from experiments #2 and #3 had a very similar appearance compared to the sulfur samples from the Kemp Caldera (Figure 4). Some very fine-grained elemental sulfur (fitting through the 2 µm in-line Ti-filter) was removed from the cell into the syringe or precipitated from the solution upon rapid cooling and depressurization. This sulfur resembles the liquid S0 at Toxic Castle (Figure 4A). On the other hand, the sulfur from the cooled reaction cell is fine-crystalline as it is at Great Wall (Figure 4B).

The amounts of sulfate (as BaSO4) and sulfide (as Ag2S) obtained from the subsamples (ca. 5 or 10 mL) and the elemental sulfur retrieved from the much larger residual volume left in the Ti-cell, i.e., ∼45 or ∼35 mL were both extrapolated to match the initial 60 mL (see Table 1). The total amounts of the different sulfur compounds retrieved from the experiment and their relative proportions indicate which reactions must have dominated in the system. Elemental sulfur is by far the most abundant, H2S is only a small fraction of the initial amount, and sulfate concentration is also low. The experimental design is not geared towards full recovery of all species and phases, and hence the final concentrations reported do not add up to the amount of sulfur present in system (30 mmol/L in total or 1.8 mmol in the 60 mL volume of the reaction cell). We suspect that the missing sulfur is mainly represented by a coating on the inner walls of the reaction cell, which could not be fully retrieved after the experiment was terminated. A small fraction of the H2S may be sorbed to elemental sulfur (e.g., Bacon et al., 1943).

3.2 Mass balance of sulfur species

Our experimental results indicate that the largest fractionation of the sulfur formed during the experiments could not have been due to SO2 disproportionation. This can easily be seen by the data presented in Table 1. First, less than 0.1 mmol of the original 1.2 mmol sulfide in the reaction cell remained unreacted. This shows that sulfide was not produced during SO2 disproportionation (Eq. 1), but instead it was consumed (such as in reaction 3). Second, disproportionation should produce twice as much sulfate than sulfur (see Eq. 2). But in the observed reaction product the amount of sulfur is greater than the amount of sulfate. The development of abundant elemental sulfur in concert with the pronounced drop in sulfide concentration can only be explained if synproportionation (Eq. 3) occurred in the reactor.

3.3 Sulfur isotopes

Isotopic compositions for the reactants Na2S · 3 H2O, Na2SO3 and S0 (used as crystallization nucleus) were determined along with that of the S0, H2S and SO4 fractions formed during the experiments (Table 1). Isotopic compositions for H2S were determined from precipitated Ag2S. Elemental sulfur in experiment #1 was only precipitated during sample processing and is clearly different in morphology from that produced in experiments #2 and #3. The sulfur produced in those later experiments has δ34S values close to 0‰ in both instances (Table 1). The sulfur isotopic composition of H2S is only 1.1‰ higher than those of S0 which is consistent with an expected small equilibrium fractionation between native sulfur and H2S (Ohmoto and Rye, 1979).

3.4 Sulfur isotope fractionation models

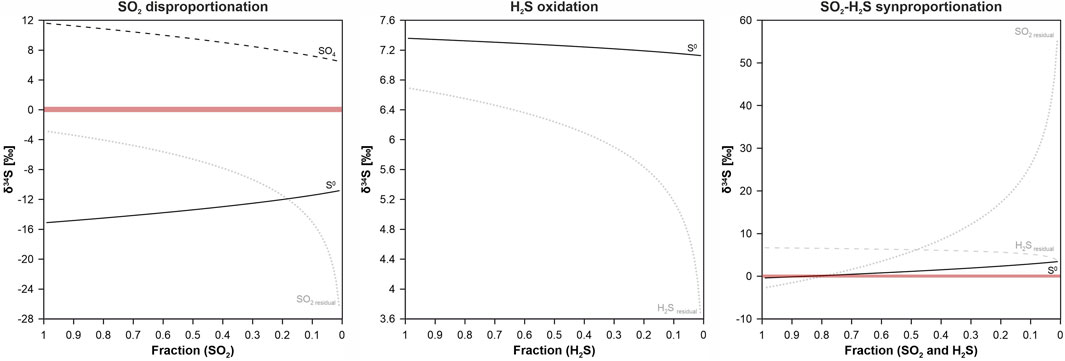

To further illuminate the sulfur formation process, we used the known initial isotopic composition of the reactants (Table 1) to construct a set of Rayleigh fractionation models for the different possible formation pathways (see Supplementary Material for details) and plotted the results together with the measured isotopic values of the sulfur recovered from the experiments (Figure 5). Another sulfur formation mechanism could be SO4 reduction, but these values could not be calculated because we did not have an initial δ34SSO4 value due to no existing sulfate at the beginning of the experiment.

FIGURE 5. Results of expected δ34S values for sulfur formed by SO2 disproportionation, H2S oxidation and synproportionation of SO2 and H2S at 220°C. The horizontal red bars represent the measured δ34S values of elemental sulfur obtained from the experiments (δ34S = −0.3 to 0.4‰). The calculated isotopic composition for H2S oxidation ranging from 7.12 to 7.36‰ plot outside the measured δ34S range of elemental sulfur. The δ34S range for SO2 disproportionation shows values between −15.1 and −10.6‰, which are far too negative. Only the sulfur values predicted for SO2–H2S synproportionation (δ34S = −0.12 to 1.2‰) fit with the measured δ34S values of sulfur.

The calculated values for H2S oxidation as well as SO2 disproportionation fall outside the measured range because they are either far too negative or too positive (see Figure 5). Thus, these reactions can be excluded as a possible sulfur formation process. However, the calculation results suggest that δ34SS values resulting from SO2–H2S synproportionation are consistent with the measured sulfur isotope values (δ34S = −0.3 to 0.4‰) of elemental sulfur retrieved from experiments #2 and #3.

3.5 Thermodynamic/kinetic model

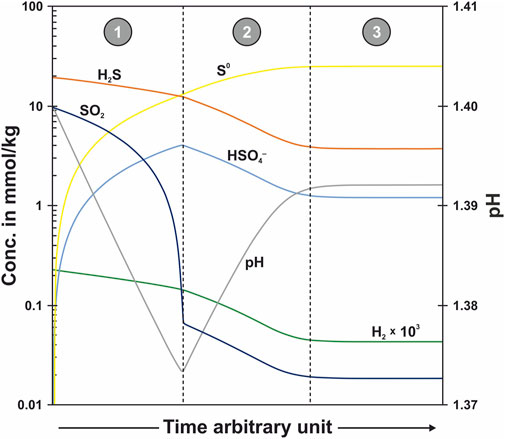

In addition to supposing specific sulfur redox reactions and studying their isotopic consequences, we conducted an arbitrary kinetics reaction path model computation to examine the predicted sequence in a hypothetical network of ten reactions (between the considered four oxidation states of sulfur (−2, 0, +4 and +6) there are 4!/((4–2)!*2!) = 6 possible simple redox reactions with two reaction partners and 4!/((4–3)!*3!) = 4 possible syn-/disproportionation reactions with three reaction partners; Supplementary Figure S1). The model predicts which of these reactions is expected to contribute how much to the total reaction turn-over as the system approaches equilibrium (Figure 6). Starting with initial concentrations of 10 mM SO2 and 20 mM H2S in the reaction cell (t = 0), two reactions are predicted to dominate in the first time-segment: (1) SO2–H2S synproportionation and (2) SO2 disproportionation to S0 and HSO4−. As SO2 is consumed and HSO4− is produced in these reactions, the Gibbs energies of the reactions change. The affinity for the SO2–H2S synproportionation will go down, while those for reactions with HSO4− will go up. The transition from the first to the second time-segment is reached when the SO2 disproportionation turns endergonic and H2S–HSO4– synproportionation turns exergonic. SO2–H2S synproportionation continues to create small amounts of S0. In reaching equilibrium, of the 30 mM total sulfur dissolved initially, 25 mM are predicted to have been converted to S0, of which 23 mM are due to synproportionation (roughly equal contributions from SO2–H2S and H2S–HSO4–) and 2 mM are due to SO2 disproportionation. Equilibrium concentrations of H2S and HSO4− are 3.7 and 1.2 mM, respectively.

FIGURE 6. Results of an arbitrary kinetics reaction path model computation. The model has initial concentrations of SO2 and H2S that match those at the start of the experiment. The predicted sequence of reactions is dominated by SO2–H2S synproportionation and SO2 disproportionation in time-segment 1 and by H2S–HSO4– synproportionation (and subordinate SO2–H2S synproportionation) in time-segment 2, before equilibrium conditions are reached in time-segment 3.

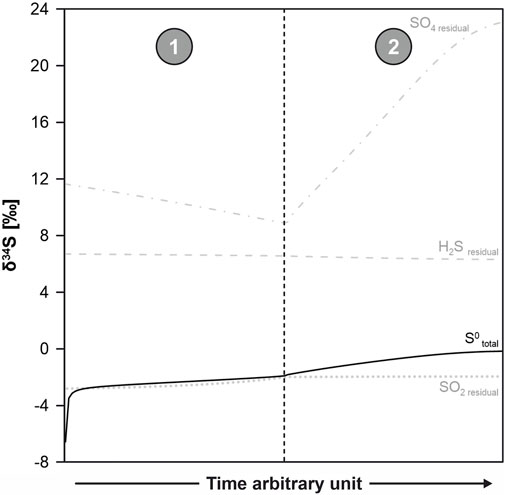

In addition to instantaneous equilibrium isotope partitioning, we used the sulfur species abundances from the GWB reaction path model to compute Rayleigh fractionation trends. Kleine et al. (2021) suggested that Rayleigh fractionation more reliably represents isotope fractionation in irreversible geochemical reactions in closed systems than the equilibrium partitioning supported by GWB. The evolution of isotopic composition of H2S, S0, SO2, and HSO4− is shown in Figure 7. The correspondence between the measured and predicted isotopic compositions is excellent for S0 and HSO4−. The measured δ34S value of the leftover H2S is lower than the predicted one.

FIGURE 7. Rayleigh fractionation trends of the geochemical reaction path model presented in Figure 6. The predicted values for δ34S of S0 are close to 0‰, which is in accordance with the measured values. Correspondence can also be observed between predicted and measured isotopic compositions of sulfate. The model δ34S of the residual H2S is higher than what was measured.

4 Discussion

4.1 Experimental evidence for sulfur formation from synproportionation

The stability of elemental sulfur in water-bearing systems is known from experimental studies of sulfur hydrolysis to H2S and SO2 as well as H2S and HSO4− (e.g., Ellis and Giggenbach, 1971). These reactions are the reverse of synproportionation discussed in this work. Formation of native sulfur by SO2–H2S synproportionation was already considered by Mizutani and Sugiura (1966) and Giggenbach (1987) as potential sulfur forming reactions in gaseous subaerial fumarole systems. Subequal amounts of both compounds in a cooling system will create thermodynamic drive for the reaction to proceed. Some H2S is expected to form when SO2 reacts with FeO in the rock through which the fumarole gas flows and undergoes cooling (Giggenbach, 1987). Hence low-temperature fumaroles in many volcanoes have both gases present in subequal amounts, and hence elemental sulfur can form by synproportionation of SO2 and H2S in the gas phase. It was unclear what the energetics and kinetics of the reaction in aqueous solutions under hydrothermal conditions are.

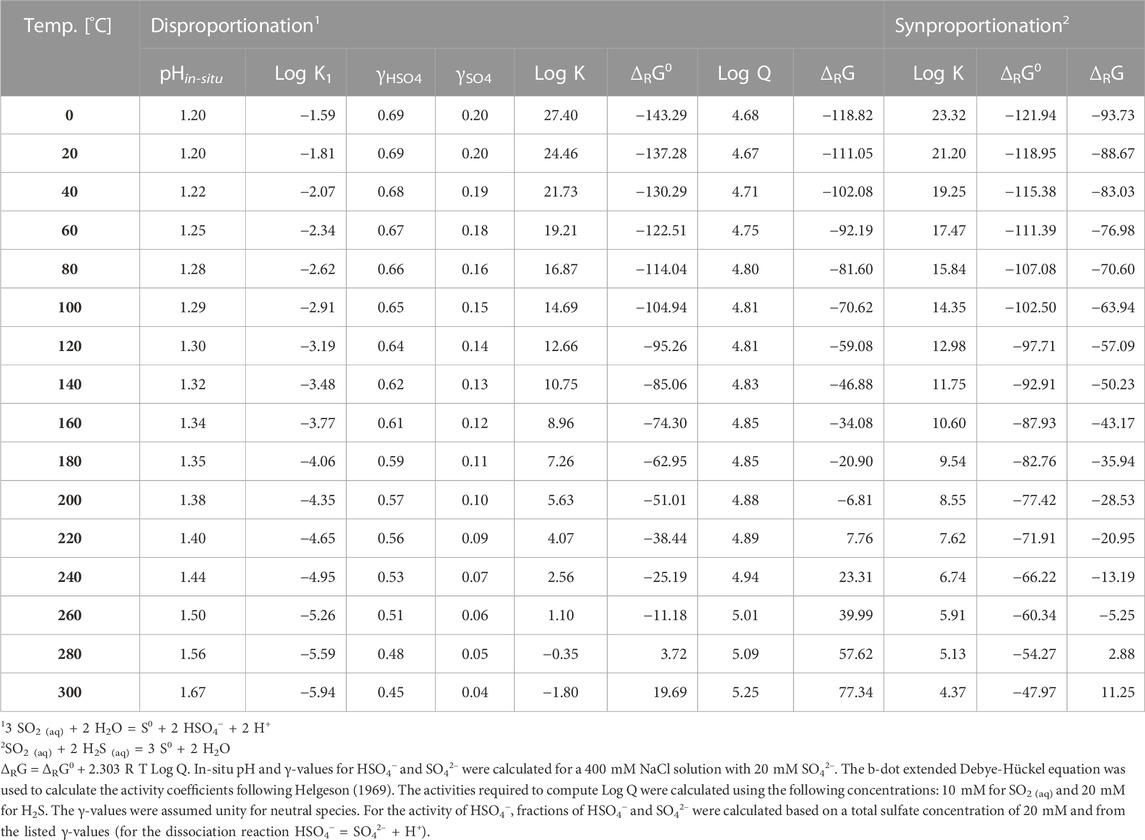

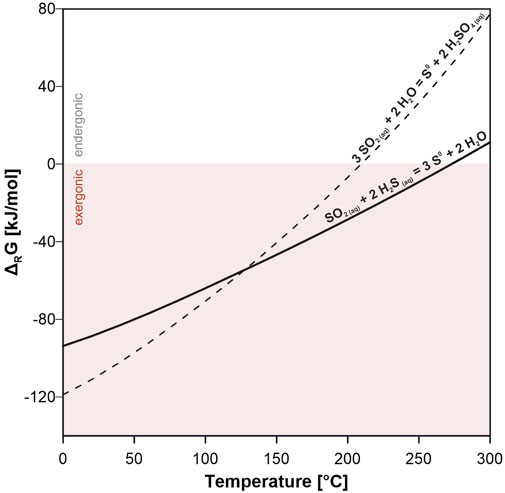

The energetics of native sulfur formation in an aqueous environment by synproportionation was examined by Kürzinger et al. (2022) for the Kemp Caldera, but the thermodynamic computations presented in this earlier communication were subject to large uncertainties in pH and sulfite concentrations of the hydrothermal fluids. Based on the new tight experimental constraints, we here reevaluate the energetics of the syn- and disproportionation pathways of elemental sulfur formation. For the measured low pH25°C of ∼1.2 in experiments #2 and #3, the dissociation equilibrium is predicted to lie entirely on the undissociated side with sulfite and sulfide being dominated entirely by SO2 and H2S, respectively (see Figure 14 in Kürzinger et al., 2022). Results for ΔRG for the dis- and synproportionation reactions over a temperature range from 0 to 300°C are listed in Table 2. They were calculated using the concentrations and activity coefficients (γ) provided in the footnote of Table 2 and are shown in Figure 8.

TABLE 2. Log K, standard state Gibbs energy (ΔRG0) and Gibbs energy (ΔRG) values for dis- and synproportionation reactions over a temperature range from 0 to 300°C and constant pressures (p = 30 MPa).

FIGURE 8. Gibbs energies per moles of disproportionation (3 SO2 (aq) + 2 H2O = S0 + 2 H2SO4 (aq)) and synproportionation (SO2 (aq) + 2 H2S (aq) = 3 S0 + 2 H2O) reactions as function of temperature at isobaric conditions (p = 30 MPa). Synproportionation stays exergonic up to 275°C, while disproportionation reaches a chemical equilibrium at ∼210°C. See Table 2 for details.

At lower temperatures, both reactions are clearly exergonic, while the disproportionation reaction becomes endergonic at temperatures >210°C. Synproportionation, however, remains exergonic up to a temperature of about 275°C at the selected conditions (p = 30 MPa). From an energetic perspective, both reactions are likely to occur in the experiment. But even if the disproportionation reaction is endergonic at the target temperature of 220°C, this sulfur formation process cannot be entirely excluded. The experimentally produced elemental sulfur could have formed by disproportionation during the cooling phase as the system passed through the temperature range in which this reaction would be predicted to take place.

The elevated sulfate concentrations measured indicate that sulfate was formed by disproportionation reactions that took place subordinated to synproportionation. The reaction path model predicts that sulfate is formed by disproportionation alongside native sulfur early on in the reaction sequence. The predicted quantities are 2 mM of S0 and 4 mM of sulfate. As SO2 gets depleted and sulfate is enriched in solution, the energetics changes such that the synproportionation of sulfate and H2S becomes exergonic, while sulfite-sulfide synproportionation continues with a small reaction turnover.

The formation of H2 in the experiment, although in very small amounts of 5–10 μmol/L, indicates that another, subordinate reaction must have taken place in addition to the dominant synproportionation. A possible origin of the detected H2 can be the partial oxidation of SO2 with water as oxidant (Eq. 8).

Using the concentrations and activity coefficients from Table 1 and 2 in concert with a calculated equilibrium constant (Log K220 °C = 7.3) for Eq. 8, the measured H2 concentrations correspond with the amount of H2 predicted for equilibrium state in a pH 1.4 solution with 10 mM SO2 and 2–6 mmol sulfate at 220°C. The reaction path model results suggest equilibrium concentrations of H2 (4 µM) that are very close to the measured concentrations (Table 1). These results hence indicate that sulfate and SO2 did indeed equilibrate in the hydrothermal apparatus. The formation of sulfuric acid plus H2 by partial SO2 oxidation could also explain why low pH may develop in systems in which SO2 disproportionation is subordinate to SO2–H2S synproportionation.

In the conducted experiments, native sulfur was the most abundant sulfur species (4.6–6.75 mmol/L) and >10 times more abundant than sulfate (0.31–0.56 mmol/L) and sulfide (0.11–0.24 mmol/L). While the mass balance indicates that sulfur formation by synproportionation was dominant, the experimental setup was not optimized for allowing full retrieval of all sulfur species. It is hence not unexpected that the sum of the retrieved sulfur species does not add up to 30 mmol/L (the total sulfur concentration in the system). In the model, of the 25 mM S0 produced, 2 mM are from SO2 disproportionation and roughly 11.5 mM each are due to synproportionation of SO2–H2S and H2S–HSO4–, respectively.

The predicted isotopic composition of the native sulfur (0‰) is also in agreement with the measured δ34S values (cf. Table 1; Figure 5). The predicted δ34S value of sulfate is in the range of 23‰ at 220 °C and very close to the measured value of 23.6‰. We hence suggest that the sulfate produced in the experiments has been formed by disproportionation and (to a lesser extent) by partial oxidation of the residual SO2 (Eq. 8). As SO2 is highly soluble in water and because of its intermediate oxidation state, it can act as reducing and oxidizing agent.

The residual H2S has measured δ34S values that are 1.1‰ higher than that of the S0. The Rayleigh model predicts a higher δ34S value (6.3‰) for H2S than the 0.8‰–1.5‰ measured. Experimental data for H2S–S0 fractionation (Ohmoto and Rye, 1979) suggest that, in equilibrium, H2S is 0.7‰ lighter than S0. The measured difference of 1.1‰ is closer to the expected equilibrium value than the difference of the difference of 6.3‰ predicted by the Rayleigh model. This result may indicate that the small amount of H2S left over in the experiment was close to equilibrium with the abundant S0 that had formed primarily by synproportionation.

4.2 Implications for the isotopic composition of elemental sulfur in submarine arc/back-arc hydrothermal systems

Disproportionation of magmatic SO2 in arc/back-arc magmatic-hydrothermal systems forms acid-sulfate type fluids with pH-values <3 (Gamo et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2009; de Ronde et al., 2011; Seewald et al., 2019). SO2 degassing is common in these environments due to the oxidized nature of magma produced above a subducting slab (Wallace, 2005). Experimental and empirical studies (cf. Kusakabe et al., 2000; McDermott et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2021) have shown that the disproportionation-derived sulfate is enriched in 34S, whereas the reduced counterparts (S0 and H2S) are depleted in 34S relative to the isotopic composition of the influxing SO2, which ranges between 4 and 10‰ in δ34S (Hannington et al., 2005). The temperature-dependent equilibrium isotope fractionation between aqueous SO2, SO4, S0 and H2S has been established (Ohmoto and Rye, 1979; Ohmoto and Lasaga, 1982; Kusakabe et al., 2000) and these constraints were used to compute the isotopic evolution of SO2 and the products of the disproportionation reactions in hydrothermal fluids (McDermott et al., 2015; Kleine et al., 2021; Peters et al., 2021). The results from these studies suggest that the δ34S values of elemental sulfur are typically <0‰ and those of the associated sulfate are commonly <21‰. The equilibrium isotope fractionation between native sulfur and H2S is very small (Ohmoto and Rye, 1979), hence sulfides in arc/back-arc vent settings are usually also characterized by δ34S values <0‰. Often, the δ34S value of S0 is lower than that of the dissolved H2S (e.g., Peters et al., 2021), which may indicate that the S0 formed at lower temperatures than the H2S.

Although both sulfur and sulfide typically have negative values of δ34S, positive values for S0 and H2S have also been documented in various hydrothermal systems. For instance, hydrothermal fluids at Niuatahi volcano (NE Lau Basin) display positive δ34SH2S values ranging from 0.2 to 4.5‰ (Peters et al., 2021). Other examples include the Macauley and Brothers hydrothermal system, both hosted in submarine caldera volcanoes the Kermadec arc. The Macauley white smoker vent field is close to the summit of a dacitic cone near the SE caldera wall. Here, S0 with a δ34S value of −3.4‰ precipitates from highly acidic fluids with δ34SH2S values between 1.6 and 2.9‰ (Kleint et al., 2019; Peters et al., 2021). Brothers volcano hosts several chemically distinct active hydrothermal sites (e.g., de Ronde et al., 2005; de Ronde et al., 2011). Whereas the NW Caldera and Upper Caldera sites are dominated by black smoker-type fluids and Cu-Fe-rich sulfide chimneys, the Upper and Lower Cone vent fields are characterized by white smoker venting and the occurrence of elemental sulfur. Fluids of Brothers Upper Caldera show δ34S values between 3.0 and 4.6‰ for dissolved sulfide (Kleint et al., 2019; Peters et al., 2021), while the Cone vent fluids are negative (δ34SH2S = −8.0 to −4.8‰; de Ronde et al., 2011). Niua, a volcano located in the northernmost Tonga arc, hosts two active vent sites (δ34SH2S = 2.6 to 4.5‰; Peters et al., 2021), but positive S0 was only found at Niua North, exhibiting a δ34S value of 3.1‰ (Peters et al., 2021). Even higher isotope values for elemental sulfur in the range from 5 to 6‰ from active vents in the Kemp Caldera (South Sandwich arc) were reported by Kürzinger et al. (2022). The very large range in the isotopic composition of sulfur and sulfide in arc/back-arc hydrothermal systems could be an indication of multiple pathways of sulfur formation mechanisms due to essential differences in redox, which allows for variable proportions of SO2 and H2S to be added to the hydrothermal system (cf. Kusakabe et al., 2000).

Kürzinger et al. (2022) proposed that the high δ34SS values observed in the Kemp Caldera are inconsistent with disproportionation of SO2 and instead suggested that the S0 is formed by SO2–H2S synproportionation. The experimental findings presented here provide irrefutable evidences that this novel S0 formation pathway does indeed take place if energetically favorable conditions prevail. Our experimental results clearly show that the synproportionation of SO2 and H2S is a feasible process given that SO2 and H2S are both abundantly present. An essential requirement for the reaction to take place in nature is the simultaneous degassing of both SO2 and H2S. Work on fumarolic gases at convergent margin volcanoes (Giggenbach, 1987; Symonds et al., 1994; Moretti et al., 2013) has shown that the ratios of SO2 and H2S can be highly variable and that both gases can be abundant, in particular in low-temperature fumaroles.

If H2S does not degas coevally with SO2, disproportionation would then dominate in the reaction network controlling the sulfur speciation and isotopic fractionation. The common occurrence of isotopically light sulfur in submarine arc/back-arc hydrothermal systems suggests that SO2 is frequently the dominant sulfur species added to hydrothermal systems by magma degassing. The observations of isotopically heavy sulfur in places like Niua North and the Kemp Caldera, however, are inconsistent with SO2 disproportionation as formation process. Our work shows that synproportionation can be invoked to explain seafloor hydrothermal S0 with such positive δ34S values.

5 Summary and conclusion

We have presented three lines of evidence (mass balance, energetics and isotopic composition) to demonstrate that synproportionation can explain the formation of S0 in our experiments. The experimental results presented in this study demonstrated the feasibility of SO2–H2S and possibly also synproportionation as additional pathway of S0 formation in submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems hosted in arc/back-arc settings. This pathway had been suggested to operate in fumarolic gases but is novel for aqueous systems. We demonstrate that SO2–H2S synproportionation to elemental sulfur does take place rapidly in single-phase aqueous solutions based on mass balance constraints, thermodynamic computations, and isotopic fractionation modelling. Specifically, the amount of S0 formed in the experiments greatly exceeds the amount of experimentally produced sulfate. Also, at the pT-conditions of the experiments (20–30 MPa, 220°C), synproportionation of SO2 and H2S is energetically favorable, while SO2 disproportionation is not. Finally, the experimentally generated elemental sulfur in this study has an isotopic composition that is consistent with values predicted by a Rayleigh fractionation model for synproportionation. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that the sulfur formation mechanism by SO2–H2S synproportionation can not only occur in a fumarolic gas phase but also proceed in aqueous solutions of hydrothermal environments. The experimental findings and reaction path model results indicate that H2S–HSO4– may also take place in systems with low SO2 contents. The reactions went to completion within a day, indicating that these reactions are not kinetically inhibited in aqueous solutions.

We conclude that synproportionation of dissolved H2S and oxidized sulfur species may represent a previously overlooked source of isotopically heavy sulfur in submarine magmatic-hydrothermal systems.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VK, CTH and WB planned the study; VK and CTH conducted the experiments with support by SW; HS provided the S isotopic data; VK created all figures and wrote the first draft, CTH and WB helped interpretating data and write the paper, all authors read the paper and provided input; VK computed energetics and isotope fractionation assisted by WB; WB conducted the reaction path modelling.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy, EXC-2077—390741603. Earlier funding for building the hydrothermal apparatus was provided by a MARUM incentive fund to WB.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Witte for the support with SEM-EDX analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2023.1132794/full#supplementary-material

References

Bacon, R. F., and Fanelli, R. (1943). The viscosity of sulfur. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 65 (4). doi:10.1021/ja01244a043

Butterfield, D. A., Nakamura, K. I., Takano, B., Lilley, M. D., Lupton, J. E., Resing, J. A., et al. (2011). High SO2 flux, sulfur accumulation, and gas fractionation at an erupting submarine volcano. Geology 39 (9), 803–806. doi:10.1130/G31901.1

Chiodini, G., Cioni, R., and Marini, L. (1993). Reactions governing the chemistry of crater fumaroles from Vulcano Island, Italy, and implications for volcanic surveillance. Appl. Geochem. 8 (4), 357–371. doi:10.1016/0883-2927(93)90004-z

de Ronde, C. E. J., Chadwick, W. W., Ditchburn, R. G., Embley, R. W., Tunnicliffe, V., Baker, E. T., et al. (2015). “Molten sulfur lakes of intraoceanic arc volcanoes,” in Dmitri Rouwet, Bruce Christenson, Franco Tassi und Jean Vandemeulebrouck (Hg.): Volcanic Lakes (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg Advances in Volcanology, 261–288. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36833-2_11

de Ronde, C. E. J., Hannington, M. D., Stoffers, P., Wright, I. C., Ditchburn, R. G., Reyes, A. G., et al. (2005). Evolution of a submarine magmatic-hydrothermal system: Brothers volcano, southern Kermadec arc, New Zealand. N. Z. 100 (6), 1097–1133. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.100.6.1097

de Ronde, C. E. J., Massoth, G. J., Butterfield, D. A., Christenson, B. W., Ishibashi, J., Ditchburn, R. G., et al. (2011). Submarine hydrothermal activity and gold-rich mineralization at Brothers volcano, Kermadec arc, New Zealand. Min. Deposita 46 (5-6), 541–584. doi:10.1007/s00126-011-0345-8

Dick, J. M. (2019). Chnosz: Thermodynamic calculations and diagrams for geochemistry. Front. Earth Sci. 7. doi:10.3389/feart.2019.00180

Dickson, F. W., Blount, C. W., and Tunell, G. (1963). Use of hydrothermal solution equipment to determine the solubility of anhydrite in water from 100 degrees C to 275 degrees C and from 1 bar to 1000 bars pressure. Am. J. Sci. 261 (1), 61–78. doi:10.2475/ajs.261.1.61

Ellis, A., and Giggenbach, W. (1971). Hydrogen sulphide ionization and sulphur hydrolysis in high temperature solution. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 35 (3), 247–260. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(71)90036-6

Fischer, T. P., Giggenbach, W. F., Sano, Y., and Williams, S. N. (1998). Fluxes and sources of volatiles discharged from Kudryavy, a subduction zone volcano, Kurile Islands. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160 (1-2), 81–96. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00086-7

Gamo, T., Okamura, K., Charlou, J.-L., Urabe, T., Auzende, J.-M., Ishibashi, J., et al. (1997). Acidic and sulfate-rich hydrothermal fluids from the Manus back-arc basin, Papua New Guinea. Geology 25 (2), 139–142. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0139:AASRHF>2.3

Gena, K. R., Chiba, H., Mizuta, T., and Matsubaya, O. (2006). Hydrogen, oxygen and sulfur isotope studies of seafloor hydrothermal system at the Desmos caldera, manus back-arc basin, Papua New Guinea: An analogue of terrestrial acid hot crater-lake. Resour. Geol. 56 (2), 183–190. doi:10.1111/j.1751-3928.2006.tb00278.x

Giggenbach, W. F. (1987). Redox processes governing the chemistry of fumarolic gas discharges from White Island, New Zealand. Appl. Geochem. 2 (2), 143–161. doi:10.1016/0883-2927(87)90030-8

Hannington, M. D., Ronde, C. D. J. de, and Petersen, S. (2005). “Sea-floor tectonics and submarine hydrothermal systems,” in Economic geology 100th anniversary volume. Littelton. Editors J. W. Hedenquist, J. F. H. Thompson, R. J. Goldfarb, and J. P. Richards (Hg (Colorado, USA: Society of Economic Geologists), 111–114.

Hayashi, K., and Ohmoto, H. (1991). Solubility of gold in NaCl-and H2S-bearing aqueous solutions at 250–350°C. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 55 (8), 2111–2126. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(91)90091-I

Helgeson, H. C. (1969). Thermodynamics of hydrothermal systems at elevated temperatures and pressures. Am. J. Sci. 267 (7), 729–804. doi:10.2475/ajs.267.7.729

Herzig, P. M., Hannington, M. D., and Arribas, A. (1998). Sulfur isotopic composition of hydrothermal precipitates from the Lau back-arc: Implications for magmatic contributions to seafloor hydrothermal systems. Mineral. Deposita 33 (3), 226–237. doi:10.1007/s001260050143

Johnson, J. W., Oelkers, E. H., and Helgeson, H. C. (1992). SUPCRT92: A software package for calculating the standard molal thermodynamic properties of minerals, gases, aqueous species, and reactions from 1 to 5000 bar and 0 to 1000°C. Comput. Geosciences 18 (7), 899–947. doi:10.1016/0098-3004(92)90029-Q

Kim, J., Son, S.-K., Son, J.-W., Kim, K.-H., Shim, W. J., Kim, C. H., et al. (2009). Venting sites along the fonualei and northeast Lau spreading centers and evidence of hydrothermal activity at an off-axis caldera in the northeastern Lau Basin. Geochem. J. 43 (1), 1–13. doi:10.2343/geochemj.0.0164

Kleine, B. I., Gunnarsson-Robin, J., Kamunya, K. M., Ono, S., and Stefánsson, A. (2021). Source controls on sulfur abundance and isotope fractionation in hydrothermal fluids in the Olkaria geothermal field, Kenya. Chem. Geol. 582, 120446. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120446

Kleint, C., Bach, W., Diehl, A., Fröhberg, N., Garbe-Schönberg, D., Hartmann, J. F., et al. (2019). Geochemical characterization of highly diverse hydrothermal fluids from volcanic vent systems of the Kermadec intraoceanic arc. Chem. Geol. 528, 119289. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.119289

Kürzinger, V., Diehl, A., Pereira, S. I., Strauss, H., Bohrmann, G., and Bach, W. (2022). Sulfur formation associated with coexisting sulfide minerals in the Kemp Caldera hydrothermal system, Scotia Sea. Chem. Geol. 606, 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2022.120927

Kusakabe, M., Komoda, Y., Takano, B., and Abiko, T. (2000). Sulfur isotopic effects in the disproportionation reaction of sulfur dioxide in hydrothermal fluids: Implications for the δ 34 S variations of dissolved bisulfate and elemental sulfur from active crater lakes. Geology 97 (1-4), 287–307. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00161-4

McDermott, J. M., Ono, S., Tivey, M. K., Seewald, J. S., Shanks, W. C., and Solow, A. R. (2015). Identification of sulfur sources and isotopic equilibria in submarine hot-springs using multiple sulfur isotopes. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 160, 169–187. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2015.02.016

Mizutani, Y., and Sugiura, T. (1966). The chemical equilibrium of the 2H 2 S+SO 2 =3S+2H 2 O reaction in solfataras of the nasudake volcano. BCSJ 39 (11), 2411–2414. doi:10.1246/bcsj.39.2411

Moretti, R., Arienzo, I., Civetta, L., Orsi, G., and Papale, P. (2013). Multiple magma degassing sources at an explosive volcano. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 367, 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.02.013

Ohmoto, H., and Lasaga, A. C. (1982). Kinetics of reactions between aqueous sulfates and sulfides in hydrothermal systems. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 46 (10), 1727–1745. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(82)90113-2

Ohmoto, H., and Rye, R. O. (1979). “Isotopes of sulfur and carbon,” in Geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits. 2. Editor L. Hg HubertBarnes (Edition: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 509–567.

Peters, C., Strauss, H., Haase, K., Bach, W., Ronde, C. E. de, Kleint, C., et al. (2021). SO2 disproportionation impacting hydrothermal sulfur cycling: Insights from multiple sulfur isotopes for hydrothermal fluids from the Tonga-Kermadec intraoceanic arc and the NE Lau Basin. Chem. Geol. 586, 120586. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120586

Reeves, E. P., Seewald, J. S., Saccocia, P., Bach, W., Craddock, P. R., Shanks, W. C., et al. (2011). Geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids from the PACMANUS, northeast pual and vienna woods hydrothermal fields, manus basin, Papua New Guinea. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 75 (4), 1088–1123. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2010.11.008

Seewald, J. S., Reeves, E. P., Bach, W., Saccocia, P. J., Craddock, P. R., Shanks, W. C., et al. (2015). Submarine venting of magmatic volatiles in the eastern manus basin, Papua New Guinea. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 163, 178–199. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2015.04.023

Seewald, J. S., Reeves, E. P., Bach, W., Saccocia, P. J., Craddock, P. R., Walsh, E., et al. (2019). Geochemistry of hot-springs at the SuSu Knolls hydrothermal field, Eastern Manus Basin: Advanced argillic alteration and vent fluid acidity. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 255, 25–48. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2019.03.034

Seyfried, W. E., Janecky, D. R., and Berndt, M. E. (1987). “Rocking autoclaves for hydrothermal experiments II. The flexible reaction-cell system,” in Hydrothermal experimental techniques (New Jersey, USA: Wiley-Interscience Publications), 216–239.

Shanks, W., Bischoff, J. L., and Rosenbauer, R. J. (1981). Seawater sulfate reduction and sulfur isotope fractionation in basaltic systems: Interaction of seawater with fayalite and magnetite at 200–350°C. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 45 (11), 1977–1995. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(81)90054-5

Symonds, R. B., Rose, W. I., Bluth, G. J., and Gerlach, T. M. (1994). Volatiles in magmas. Rev. Mineralogy 30, 1–66.

Wallace, P. J., Plank, T., Edmonds, M., and Hauri, E. H. (2015). “Volatiles in magmas,” in Encyclopedia of volcanoes. Editor B. F. Hg Haraldur Sigurdsson undHoughton. Second edition (Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier/AP, Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier), 163–183. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385938-9.00007-9

Wallace, P. J. (2005). Volatiles in subduction zone magmas: Concentrations and fluxes based on melt inclusion and volcanic gas data. Geology 140 (1-3), 217–240. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.07.023

Keywords: elemental sulfur (S0), positive δ34S values, synproportionation, experimental geochemistry, geochemical reaction path modeling

Citation: Kürzinger V, Hansen CT, Strauss H, Wu S and Bach W (2023) Experimental evidence for the hydrothermal formation of native sulfur by synproportionation. Front. Earth Sci. 11:1132794. doi: 10.3389/feart.2023.1132794

Received: 27 December 2022; Accepted: 24 May 2023;

Published: 07 June 2023.

Edited by:

Teresa Scolamacchia, A.S.S.E.T. -Regione Puglia, ItalyReviewed by:

Barbara I. Kleine, University of Iceland, IcelandBruce Christenson, GNS Science, New Zealand

Copyright © 2023 Kürzinger, Hansen, Strauss, Wu and Bach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria Kürzinger, vkuerzinger@marum.de

Victoria Kürzinger

Victoria Kürzinger Christian T. Hansen

Christian T. Hansen Harald Strauss

Harald Strauss Shijun Wu

Shijun Wu Wolfgang Bach

Wolfgang Bach