- In 1977, two mathematicians created a conjecture that proposed the minimum size a paper strip needed to be in order to form an embedded strip.

- Although they proposed an aspect ration of 1.73 (or √3), they couldn’t prove it.

- Nearly 50 years later, a mathematician from Brown University successfully proved the conjecture, as shown in a preprint published on the arXiv server.

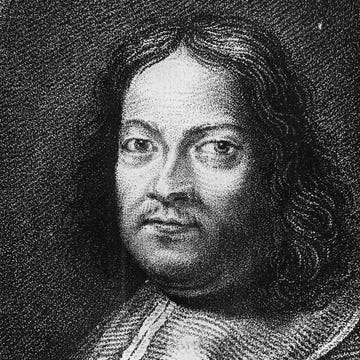

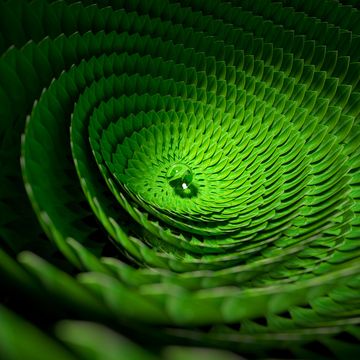

The Möbius strip is one of the most famous objects in mathematics. Discovered in 1858 by two German mathematicians—August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing—the Möbius strip is a mind-bending shape that’s actually relatively easy to make. Take a strip of paper, twist it, and attach at the ends.

But this simplicity betrays the shape’s mathematical complexity. In 1977, two mathematicians by the name Charles Sidney Weaver and Benjamin Rigler Halpern created the Halpern-Weaver Conjecture, which proposed what the minimum size of that strip of paper needs to be in order to form a Möbius strip.

Simple, right? Well, not really. There were a few rules added to this conjecture, but the big one is that the paper strip had to be “embedded” and not “immersed.” This means that the object couldn’t intersect itself at any point. In other words, the embedded paper Möbius couldn’t have any overlaps.

While Weaver and Halpern provided a proposed length, they couldn’t prove it definitely—and that’s where Brown University mathematician Richard Evan Schwartz comes in. In a paper published on the preprint server arXiv, Schwartz solves the nearly 50-year-old mystery and finally proves the minimum size proposed by the original Halpern-Weaver conjecture—an aspect ratio of 1.73, or √3.

“Möbius bands, they have these straight lines on them. They’re [what are] called ‘ruled surfaces,’” Schwartz told Scientific American. “Whenever you have paper in space, even if it’s in some complicated position, still, at every point, there’s a straight line through it.”

Schwartz told Scientific American that he tried various tactics for solving the problem for years until arriving at a geometric solution by breaking the problem down into more manageable pieces. To finally arrive at the correct answer, Schwartz actually fixed a pervious error in his calculations wherein he had erroneously concluded that the resulting shape of slicing a Möbius strip at a particular angle would result in a parallelogram—it was actually a trapezoid.

“Oh, my God, it’s not the parallelogram. It’s a trapezoid...the corrected calculation gave me the number that was the conjecture,” Schwartz tells Scientific American. “I was gobsmacked.... I spent, like, the next three days hardly sleeping, just writing this thing up.”

More mysteries surround the Möbius strip. For example, this conjecture only proves the minimum size of a paper Möbius with one twist—not three or more. For such a simple shape, it’s amazing that it can still remain so perplexing more than 160 years after its initial discovery.

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.