The History Behind 'Thomas The Tank Engine' Is Actually Really Dark

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

Sodor Might Represent Awdry's Need For Order

Born in 1911, Wilbert Awdry grew up with an interest in both trains and religion. His father was an Anglican vicar in Ampfield, located in Hampshire, England. When Awdry was 3 years old, his brother Carol enlisted as a WWI officer. Just 13 days after he joined, Carol lost his life on the field. Carol's passing brought the family to Wiltshire from Ampfield, as Awdry's grief-stricken father felt their hometown reminded him too much of the loss.

In 1933, Awdry earned a degree in theology and continued to work for the church until his retirement in 1965. He lived a structured life in the Anglican ministry and often deferred to the hierarchy of authority. For instance, when he expressed his disapproval of WWII, his church's bishop dismissed him from the parish. Despite this, Awdry went on to work at other Anglican churches.

Awdry lived through both WWI and WWII, which also coincided with the end of the British Empire. Many theorized that the island of Sodor, Thomas's home, represents a still-standing British Empire where efficiency and obedience remain key to survival. Awdry appeared to find comfort in order, and he thus modeled his fictional world to operate entirely according to set schedules.

- Photo: Egmont

Awdry Created 'Thomas The Tank Engine' For His Sick Son

When he was a child in Wiltshire, Awdry listened to trains from his bedroom window. In 1942, he decided to write stories inspired by these early memories to entertain his son, Christopher, who had fallen ill with measles. Christopher loved the stories, so much so that he began questioning his father's inconsistencies.

To keep his story straight, Awdry started writing the stories down and adding illustrations. At Christmastime in 1942, Awdry made a wooden replica of a steam engine and gave it a face. He named it Thomas.

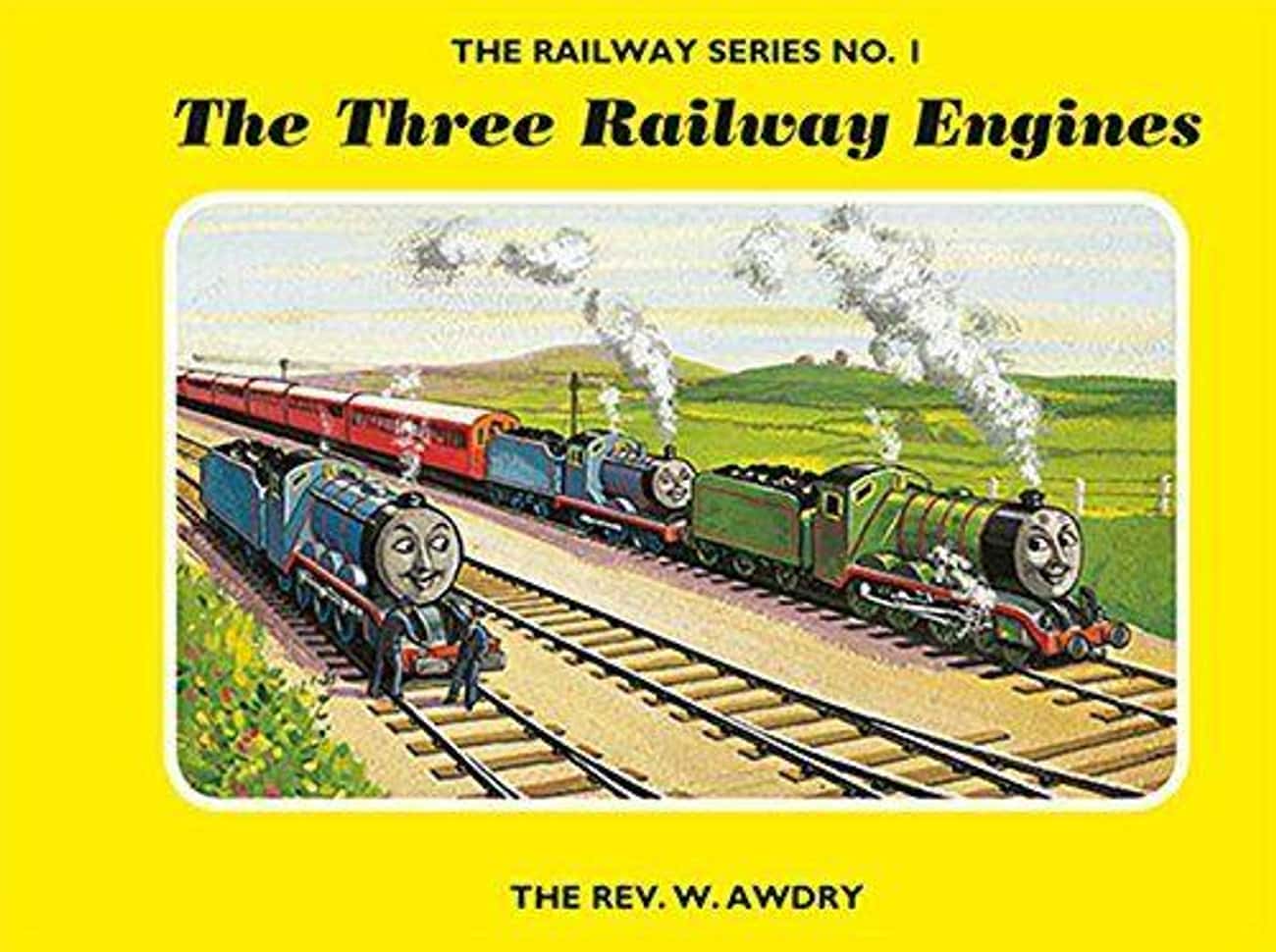

On the urging of his wife, Awdry shopped his stories around until 1945, when a publisher named Edmund Ward took on the project, then-titled The Three Railway Engines.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

Every Engine On Sodor Is Obsessed With Being Useful

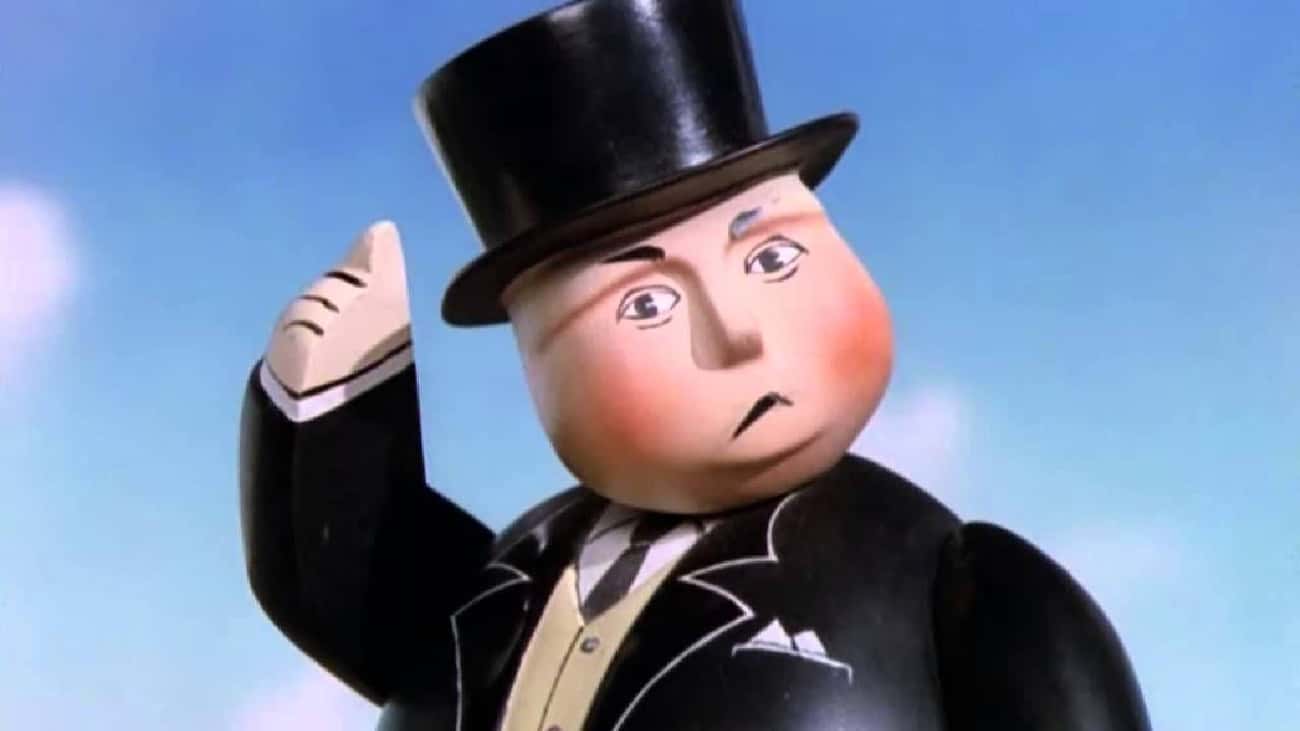

On Sodor, every engine and car hopes to achieve usefulness. Many times, the engines even remind each other to work hard and be useful. Sir Topham Hatt reminds the trains that lazy and unproductive convoys end up in the scrapyard.

As a result, individuality remains in short supply on Sodor. The trains live in constant fear and anxiety, so they dare not express their personal thoughts or ideas. Instead, they toe the line of a brainwashed leader who pushes usefulness as the pinnacle of existence.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

Sodor Operates Under Strict Rules And Punishment

Awdry's apparent appreciation of order and obedience seemingly spilled over from his life as a clergyman to his work of fiction, Thomas the Tank Engine. The titles of his Railway series indicates a preference for order; entries like Troublesome Engines and Troublesome Trucks suggest that those who act "out of line" - either by going on strike or being a lesser freight car - are more hassle than they're worth.

As punishment for causing trouble, superiors dish out some horrifying forms of discipline. For example, in the episode entitled "Come Out, Henry!" the title character Henry refuses to leave a train tunnel to work, fearing that rain will ruin his green paint. Consequently, in the English version, Sir Topham Hatt takes Henry's tracks forever, leaving Henry to spend the rest of his life in the tunnel.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

Sodor Has A Rigid Hierarchy

Unsurprisingly, facets from Awdry's life as a clergyman, a profession enshrined in hierarchy, entered his work. Awdry's characters live within a rigid structure. In the Railway series, the engines are the "big dogs," and the freight cars are apparently their subordinates. The freight cars, known as the "troublesome trucks" or "foolish freight cars," frequently play tricks on the engines and generally take it easy.

Awdry often portrays the superiors punishing the less powerful for insubordination, including in the story of S.C. Ruffey, a freight car. After S.C. Ruffey annoys Oliver, a Great Western tank engine, the freight car gets pulled apart. When Sir Topham Hatt discovers this, instead of punishing Oliver, he asks him to keep it a secret, as it would be "bad for discipline" if word got out. The trucks end up respecting Oliver out of fear they'll meet a similar fate.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

On Sodor, Characters Get Disciplined With Public Humiliation

The hierarchy of Sodor supports the ways in which Awdry doles out punishment in his Railway series. Characters who dare step out of line are frequently pointed out as examples, getting subjected to public humiliation.

In one episode of Thomas and Friends, the engine Duke tells the tale of Smudger, a tank engine. Smudger lived proudly and almost derailed himself quite a bit. Because Smudger never listened to Sir Topham Hatt, the Sodor authorities removed his wheels and turned him into a generator.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

The Engines Are Unable To Fight Sodor's System

While Sir Topham Hatt metaphorically dangles carrots for the engines, such as giving them extra chores or pulling "special" freight, he also makes sure that every engine knows its place on the tracks. On Sodor, it doesn't matter how much precious freight an engine pulls, as a freight car will always be just that, and Sir Topham Hatt will always be on top.

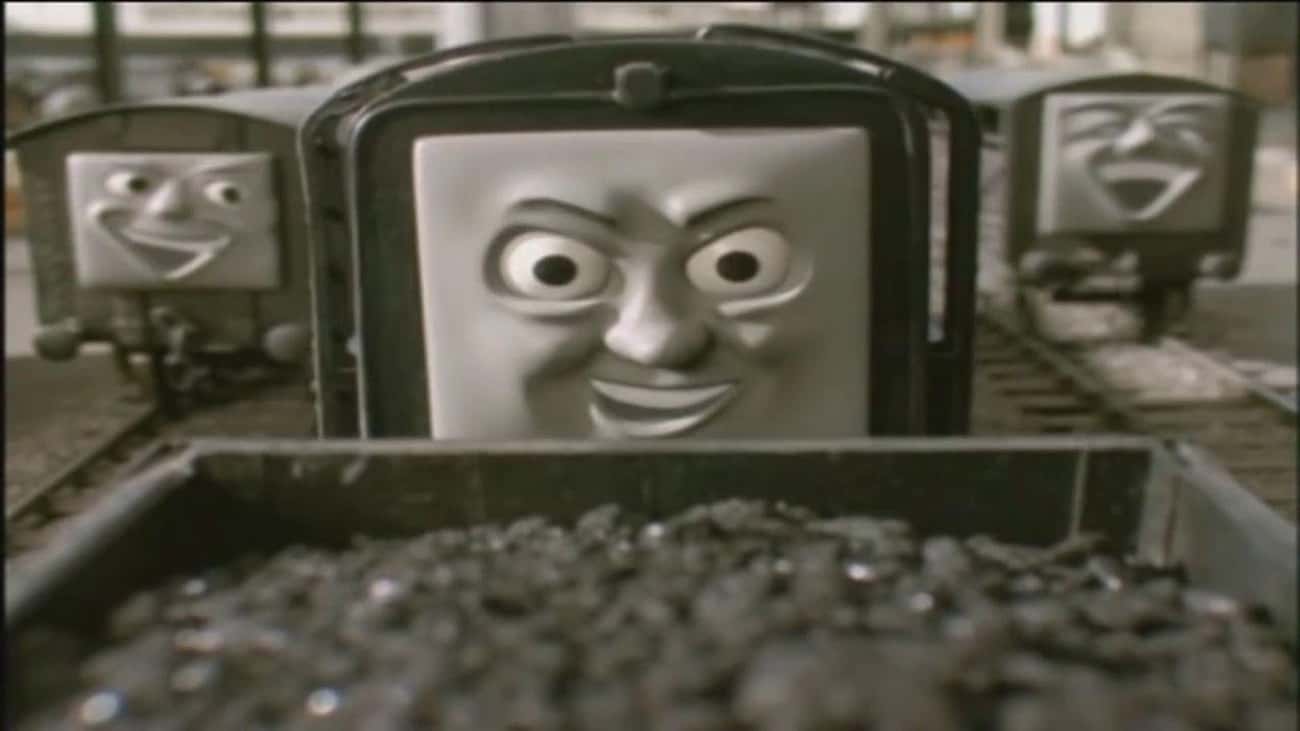

When engines try to fight this system, Sir Topham Hatt harshly rebukes them. In "Trouble in the Shed," engines Gordon, James, and Henry go on strike. Rather than listen to their demands, Sir Topham Hatt hires a scab to pull their weight while locking the three engines away for insubordination. He warns the rest of Sodor not to follow in their footsteps, lest they suffer the same fate.

By the end of the episode, the three engines feel foolish for their actions rather than horrified by their unfair treatment.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/Mattel

Sodor Is Hostile To Immigrants And New Ideas

At the same time Awdry created the world of Thomas the Tank Engine, England underwent massive changes and a status decline as an imperial power. The country experienced a significant increase in immigration due to WWII. As a result, areas like Nottingham and London experienced race-based tensions and civil unrest.

In episodes of Thomas and Friends like "Hiro Helps Out," the well-intentioned Hiro, an immigrant train from Asia, sees Sir Topham Hatt growing frazzled by the sheer amount of work he must undertake. In an attempt to help out, Hiro starts to give orders to the trains individually.

Rather than thank his employee for his assistance, Sir Topham Hatt becomes enraged, forcing Hiro to humble himself to the other trains and acknowledge his inferiority. Hiro's struggle seems eerily emblematic of the negative sentiments regarding immigration expressed during Awdry's time and even today.

Sodor appears regressive in more ways than just its politics. In the book Stafford Gets Stuck, the steam and diesel engines are at a loss at how to help out the title character Stafford, an electrical engine. The island appears content with remaining technologically disadvantaged, and it sees no widespread advances even into the '80s, though this is conveyed as quaint rather than problematic.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

Sodor Has Regressive Gender Politics, Too

The world of Thomas the Tank Engine comes up short on female characters. Those that do appear on the show are strictly coaches and never engines. Annie and Clarabel are "given" to Thomas when he starts working his branch line. As opposed to the "useful engines" who compete for work and chores, the coaches don't have much of a role beyond keeping Thomas company. They also repeat whatever he says and appear more concerned with Thomas's usefulness than their own.

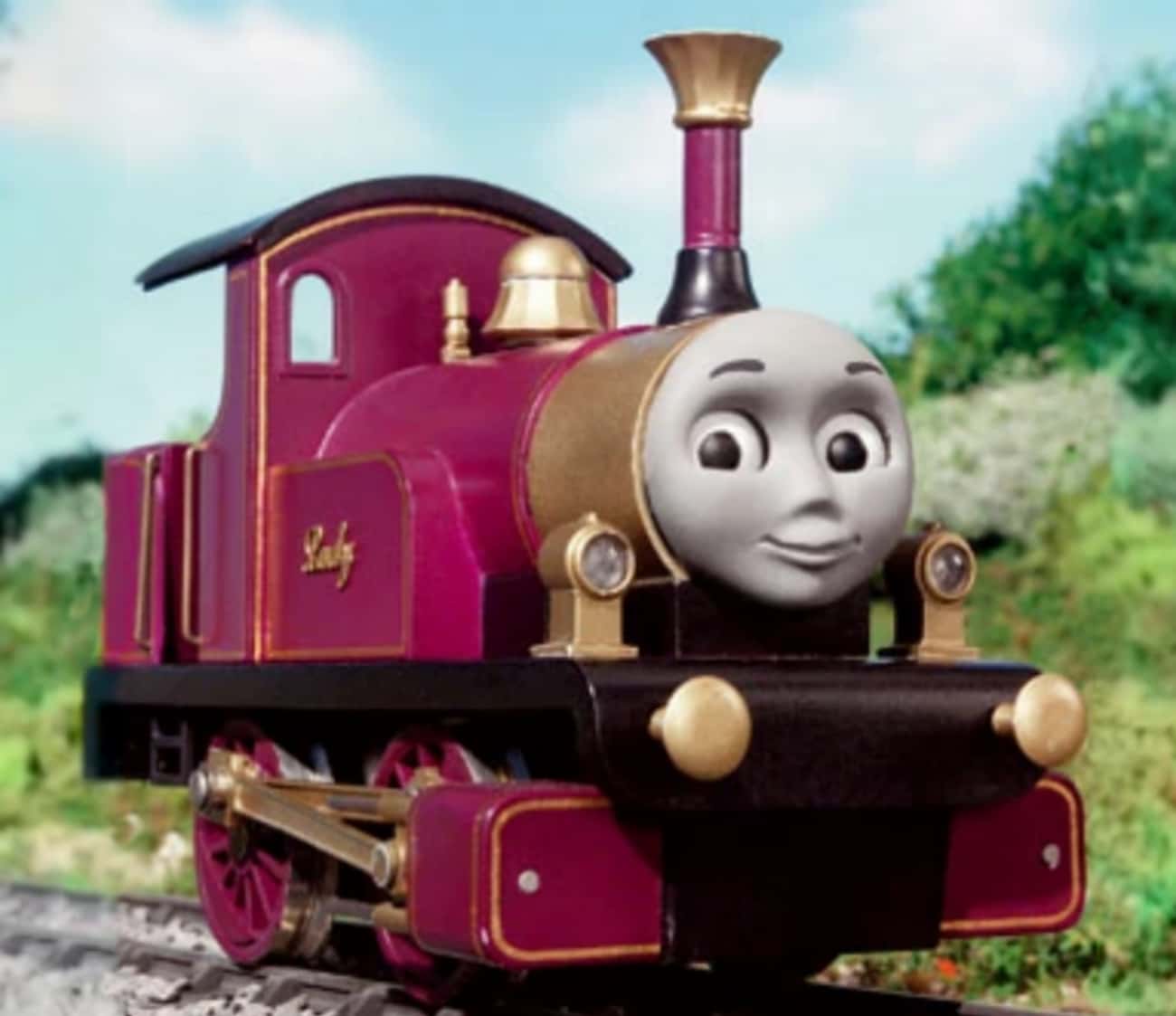

The first female engine, Lady, is literally introduced as a magical force, as if the idea of a woman engine is supernatural in and of itself. Another female train car, Daisy, gets depicted as vain and lazy rather than work-oriented like the male engines.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/ITV

The Series Hints At Troubling Parent-Child Relationships

Some readers can interpret Thomas and Friends as a story about parenting. Awdry's son Christopher, for whom Thomas the Tank Engine was created, agreed that his father saw the rail controller as a father figure and all of the engines as his children.

It's unsettling to consider the father and child dynamic in the world of Thomas the Tank Engine when you realize how quickly and harshly engines are punished for noncompliance. Engines get dismantled, altered, and locked up callously. Furthermore, Sir Topham Hatt is only pleased with the engines when they follow orders and are useful.

- Photo: Thomas & Friends/Mattel

The World Of 'Thomas' Is Authoritarian, But It's Unclear If It Glorifies Or Condemns It

Though most critical takes agree that Thomas the Tank Engine features an authoritarian regime, they often make different conjectures about what message the show wants to convey. Sir Topham Hatt routinely disciplines his engines in harsh ways, but no one ever gets fired from their service either.

Some posed the question of whether or not Sodor's engines exist within a union or under a monopoly. If Sir Topham Hatt is merely a "benevolent... baron," then Awdry's stories can be seen as a celebration of a well-run and orderly monopoly. The island always runs smoothly, and everyone - for the most part - gets along with one another and enjoys their jobs.

However, if one believes the engines work as a union on a nationalized railway like England's, one may see Awdry's stories as similar to an Ayn Rand critique of socialism. In Atlas Shrugged, Rand portrays socialism as an overarching hindrance on individuality, competition, and technological progress, areas where Sodor falls greatly behind.

Sodor, as a result of Sir Topham Hatt's influence, likely will never improve because the socialist power structure inhibits any sort of incentivized growth or reward.

As law professor Paul Horwitz puts it, Sodor represents a "pro-market" viewpoint, but one that also denounces the incorporation of status and capital. He notes how the number of blunders and errors made by trains in Sir Topham Hatt's service would result in them getting fired in a capitalist regime, and yet the controller still exhibits absolute authority over his workers.