The Jurassic Park: Trespasser team walked where no other developer dared, and paid for it

When Hollywood met Looking Glass

It was a Wednesday in March, and the Dreamworks dream team of Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen had flown into Seattle to join Bill Gates for a press conference. The four men, seated on tall Hollywood director’s chairs, were estimated to be worth a combined $11 billion - and that was in 1995 money.

Together, Dreamworks and Microsoft were going 50-50 on a new game studio, investing a total of $30 million. “I’m spoiled,” said Spielberg, as recorded by the LA Times. “I worked with the best studios and the best actors, and it would be silly to get into the interactive business without Microsoft. They’re the best company in the world. It does seem like a marriage that was destined to happen.” It was a marriage that would produce a famously strange child in Jurassic Park: Trespasser.

Over at Looking Glass Studios, a writer on the System Shock team named Austin Grossman saw potential: “People used to say, ‘The only things video games are missing is that premium talent that Hollywood has.’ It was a big deal.” Grossman arrived in California at Dreamworks Interactive alongside Seamus Blackley. From a games industry perspective, the pair were a great catch: Grossman, who had invented the audiolog and helped shape a timeless sci-fi horror premise in System Shock; Blackley, the genius behind the physics of Looking Glass simulations, who would go on to become the ‘father of Xbox’. To the men and women working in movies, however, they were nobody.

“They had never heard of us,” Grossman says. “They had no idea what it was we did or where we came from.” In all of LA, Grossman only ever met one person who cared about System Shock: a band member in ska punk sensation No Doubt. “The amount of money Looking Glass moved around was nothing to the film industry.” In fact, when Grossman and Blackley showed up at Dreamworks, they were given nothing to do. “We were gonna advise on projects or something,” Grossman says. “Which just meant we set out desks and no one wanted to talk to us.”

Meanwhile, it wasn’t exactly clear to Grossman what Dreamworks was doing either. In its pipeline were Deep Impact, a comet disaster movie, and The Prince of Egypt, “the animated Book Of Exodus”. Nothing you could easily hang a game off of. Then the news came down: Spielberg would be directing a sequel to Jurassic Park. “I thought, ‘We’re sitting here and everybody’s ignoring us. Why don’t we do a Jurassic Park game? Suddenly we’ll matter in the company, and somebody will get to actually do something,” Grossman says. “I had no particular interest in the franchise, I just thought it was a strategic play.”

In terms of approach, Jurassic Park: Trespasser would be System Shock but moreso. Emboldened by the success of that vision, the Trespasser team amplified it in every direction. “We had money at the time,” Grossman says. “We were going to take everything about System Shock and do the next step.” Blackley handled conversation with upper management. “Seamus spoke that language, he had that kind of personality,” Grossman says. “I had very little sense of managerial oversight. Seamus did a good job in getting them to leave us alone, to make a Looking Glass game the way we wanted to.”

In System Shock you woke up on a space station after a massacre, unable to leave or speak to any living soul - a conceit that enabled Looking Glass to build a cohesive world without contrived dialogue or clumsy NPC interactions. In Trespasser, similarly, you’d be stuck on an abandoned island, the Costa Rican site where Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs were researched and raised. This time, you’d be exploring not tight corridors but a wide-open ecosystem shared with imposing brachiosauruses and vicious velociraptors.

In System Shock, you controlled not just a first-person camera, but a simulated human body, powered by Blackley’s physics tech, which carried momentum and was impacted realistically by forces on the Citadel space station. “We loved the little physically simulated moments,” Grossman says. “Where somebody would shove aside a box, or a box would tumble impressively.”

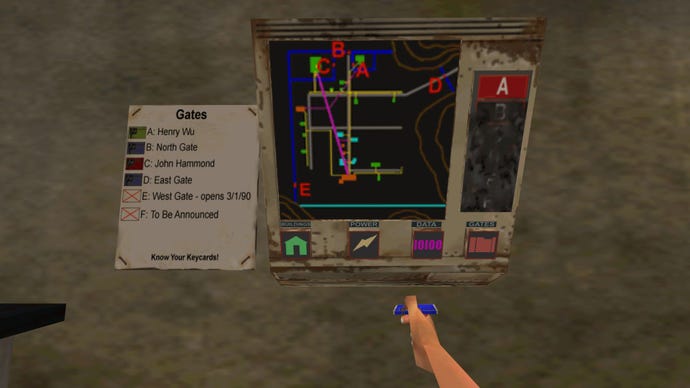

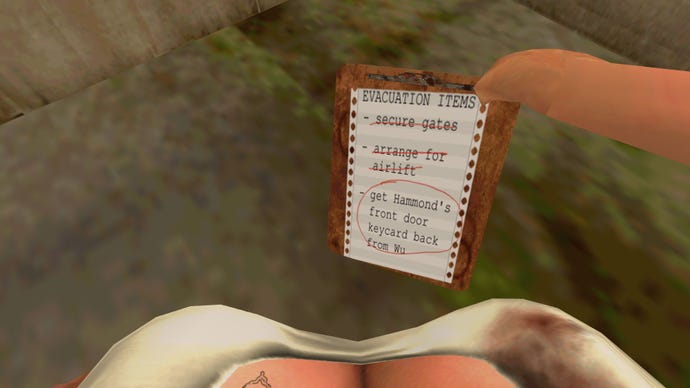

In Trespasser, Blackley and Grossman would go one further, allowing the player to manipulate practically any object in its world with an outstretched, onscreen hand. Guns, crates, keycards, the dinosaurs themselves - all would have appropriate weight and collide in unpredictable ways during exploration and conflict. Moreoever, no onscreen ammo count or health bar would distract from this first-person immersion. The result, Dreamworks hoped, would be more than an FPS.

“The vision would be this simulated world where you could shoot things, but you could also throw them or stack them up to climb and escape from [enemies],” Grossman says. “The whole mantra of emergent gameplay is that, ‘We will give the player tools, and the player can be creative about accomplishing their goals with those tools.’ The gun was a useful tool but it wasn’t the only tool. That was the theory. It was not the outcome.”

In picking a fight with physics, Dreamworks was facing off against problems very few game developers had encountered before. “The physics system didn’t work,” Grossman says. “It never worked consistently, and it was crazy-making.” Boxes would collide and fuse together, like Maltesers on a hot day. And the tech “had a hard time deciding” when an object had finally come to rest, which meant stacked crates would continue to shuffle about endlessly: “Somehow the idea of the static coefficient of friction doesn’t quite kick in.”

Unfortunately, a number of Trespasser’s puzzles insisted on the stacking of crates. And beyond that golden path of designer-approved challenges, there wasn’t a lot to see or do. Dreamworks had set up an island far larger than they could possibly fill. “The whole point of emergence in gameplay is that you have multiple systems interacting, crashing into each other and creating ripple effects,” Grossman says. “But if you have a big open outdoor space, it’s empty. The box here and the box ten metres away from it aren’t gonna interact.”

That emptiness was compounded by the limitations of Trespasser’s software renderer, which couldn’t live up to the movie fantasy. “Since we’re showing the wilderness, we have to cram a ton of foliage in to give that sense of the dense jungle they’re always running around in Jurassic Park,” Grossman says. “And of course, we couldn’t do that, because that just meant cramming a million polygons into the scene. When you start to look at the scale of an open space, and how many leaves you have to stick in it to make it credibly forested, it’s a massive amount. So we set ourselves an impossible problem there.”

Played today, in the age of walking simulators, Trespasser often feels more like Dear Esther than any FPS. As you wander across its deserted island, protagonist Anne recalls passages from the memoir of John Hammond, Jurassic Park’s fictional Scottish industrialist, narrated with typically plummy aplomb by Richard Attenborough. Grossman, now an accomplished author, wrote those passages himself. He has a knack for getting inside the head of unpardonable figures and telling their stories with reflective, endearing honesty - as evidenced by his most recent novel, Crooked, which made Richard Nixon its protagonist. Trespasser, too, told the story of an ambitious man who enabled a disaster.

Recording with Attenborough is one of Grossman’s few unequivocally happy memories of the project. “It was insane that we got him to do that script,” he says. “They flew us to Twickenham Studios, and we had one day with Attenborough, who was an incredibly fun person. Some people just know how to play the celebrity - we show up and he’s hosting the party. Everybody has a great time. And we do the script, and we all feel awesome about it. That’s a man who knew how to be famous. He made everybody feel cool and did an amazing job.”

“I think everybody there felt like games were an interesting medium that they were sort of excited by, but I don’t think [Spielberg] was interested enough to get really involved."

Extra stardust was added by Spielberg himself, who was a regular visitor to the office. “He was there all the time, because his son was really into games.” During a 20-person meeting, Spielberg’s phone would ring, and he would take the call, the entire room standing quietly until he’d concluded his conversation, “because that was what you did.” As for what the director thought of Trespasser? “I don’t think he really knew what to make of it,” Grossman says. “I think everybody there felt like games were an interesting medium that they were sort of excited by, but I don’t think he was interested enough to get really involved. He’d just come by and look over our shoulder sometimes.”

The one tangible creative contribution of the Spielbergs is a moment, midway through Trespasser’s campaign, when a velociraptor pursuing you through a ravine stops conspicuously beneath a precariously-parked jeep - which you can dutifully push onto its head. The scene is notable for departing from the unscripted design principles of Looking Glass, and also because it’s accompanied by a message scrawled on a nearby rock: “No thanks required. The pleasure is all ours.” The rock is signed, by both Spielbergs. (To his credit, the younger Spielberg, Max, stuck around: he’s credited as a designer on 2014’s Assassin’s Creed Unity).

Grossman, who went on to write for Deus Ex and Dishonored, is less wistful on the subject of Trespasser’s final year of development, when it became clear its innovations wouldn’t coalesce into a well-regarded game. While its dinosaurs were thrillingly inscrutable, fending them off with an independently controlled arm often proved absurd. “The idea that we had to represent that body visually was a complete misstep,” Grossman says. “Hitting the right level of simulation is a judgement call, and judgement calls were something we were signally poor at making.”

After launch, GameSpot named Trespasser the worst game of 1998, declaring it “monotonous and tedious to the point of nausea”.

“It was an early experience of the entire internet being mad at you at the same time,” Grossman says. “I felt it later when Rebecca Black produced that song Friday, and everyone made fun of it for months and months. I thought to myself, ‘Yeah, that’s what that was like.’ And you know what? Rebecca Black is still a musician, and she’s quite good. She has an amazing voice. Relatable.”

For years after its release, Trespasser was a laughing stock, its uncanny, waggling arm an easy punchline. Yet gradually, every one of its creative experiments has borne fruit for other developers. Mirror’s Edge made a virtue of the invisible interface and onscreen, first-person torso. Far Cry turned the exploration of an open island into a beloved formula. And Half-Life 2 figured out stable physics puzzles which, yes, still relied on the stacking of boxes. Trespasser may have been an abject failure, but the passage of time has shown its ideas to be sound.

“I think that that is true,” Grossman says. “Just makes it sadder. We could’ve been The Beatles, we felt like we were going to be, but we were not. Seamus and I were good friends, but we were never friends again after that. We just couldn’t handle it. We couldn’t look at each other.”