Many of us can now afford the once‑unthinkable luxury of making our own CDs, for one‑off music demos, mass CD duplication or general data storage. But few of us know the full story behind the numerous 'Book' standards governing the kind of data that can be stored on a CD. Mike Collins colours by numbers...

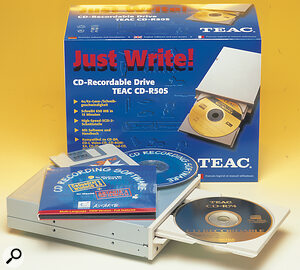

Now that you can buy a CD recorder for well under £500, and now that some computers are being supplied with a recordable CD drive built in, rather than just a CD‑ROM player, more people than ever are starting to make their own CDs. But CDs come in lots of different flavours these days: CD‑DA, CD‑ROM, CD‑ROM/XA, CD‑i and other types. Their specifications are spelt out in a series of technical documents which are known by the colours of their covers — Red Book, Yellow Book, Green Book, Orange Book, White Book and Blue Book — and it pays to know just what each format means.

History

The Compact Disc was originally developed by Philips and Sony as a means of distributing high‑quality audio to consumers — a replacement for vinyl records. The Compact Disc Digital Audio Standard, commonly referred to as the Red Book, describes the physical and logical format of these discs, which store digital audio data in a convenient form. But digital data is digital data, so why not use CDs for other forms of digital data? The same thought thought occurred to others, too, so extensions to the Red Book standard were developed for storing computer data, compressed audio, video, and graphical information on CD. It is these standards which are now typically referred to by the colour of their covers.

Technically Speaking

The information on all compact discs is divided into chunks of uniform size, called sectors, and adjoining sectors are then grouped to form tracks, which are listed in the disc's Table Of Contents (TOC), a special un‑numbered track that plays first. Every sector on every type of CD contains 3234 bytes of data, 882 bytes of which are reserved for error detection and correction code and control bytes, leaving 2352 bytes (3234 minus 882) to hold audio data in a Red Book CD‑Audio disc. One of the keys to understanding the different formats thoroughly is to look at how the other formats use this 2352 bytes of space. CD‑Audio discs use the space for digitally recorded sound and error‑correction data, while other types of CDs may contain computer data, including executable programs, text, graphics, and compressed audio or video.

- RED BOOK

Red Book is the standard for Compact Disc‑Digital Audio (CD‑DA) and was established in 1980 as the first of the 'books' which defined the CD for audio use in domestic CD players. To identify themselves, Red Book discs usually have the familiar 'Compact Disc Digital Audio' logo printed within the label area.

The Red Book standard specifies that a compact disc can have up to 99 tracks of data, with each track containing a single audio selection. These tracks are divided into blocks of data referred to as sectors. Each sector holds 3234 bytes of data, as mentioned earlier, arranged as 2352 bytes of audio data, plus two 392‑byte layers of error‑detection and error‑correction codes (commonly referred to as EDC/ECC), along with 98 control bytes which are often referred to as the sub‑codes or sub‑channels and are designated by the letters P through to W. These control bytes contain the timing information which allows the CD player to cue instantly to the beginning of each selection, display the selection's number and running time, and provide a continuous display of elapsed time.

- YELLOW BOOK

Yellow Book is the standard for Compact Disc‑Read Only Memory (CD‑ROM), and this extends the Red Book specification by adding two new track types: CD‑ROM Mode 1 and CD‑ROM Mode 2. Mode 1 tracks are designed for storing computer data, while Mode 2 tracks store compressed audio, video and picture data. Yellow Book discs usually have the words 'Data Storage' in small letters beneath the Compact Disc logo.

Mode 1 sectors include a third layer of EDC/ECC which improves the error‑detection and error‑correction capability by a factor of 1000. The extra error correction is essential because this mode is designed for storing computer data, where even the loss of one bit of data could be disastrous. (With audio, the result of losing even several bits may be inaudible.)

CD‑ROM tracks also use part of the space in the sectors for synchronisation data and a header. Let me explain: on an audio CD, the information used by the drive to position the laser pickup at a specific location is contained in the 'Q' subcode, and the Red Book specifies that this 'Q' channel information should position the pickup to an accuracy of +1 second. For audio playback applications this degree of accuracy is perfectly sufficient, but for computer applications the drive must be able to locate and retrieve a specific sector — which requires an accuracy of 1/75th of a second. It is to achieve this degree of positioning accuracy that the Yellow Book specifies the inclusion of synchronisation and header information in each sector. The sync bytes specified occur in a particular pattern (0, followed by 10 bytes of FF, followed by another 0) which allows the start of each new sector to be recognised as such. The header contains the absolute address of the sector, specified in minutes, seconds and data blocks, and also has a byte to indicate whether the sector is in a Mode 1 or Mode 2 track.

As with Red Book, each sector on the disc holds 3234 bytes of data, but Mode 1 sectors start with the 12 bytes of sync data, followed by 4 bytes of header information. The space for user data is 2048 bytes and this is followed by the extra layer of error correction, which consists of 4 bytes of EDC, 8 bytes of blank space, and 276 bytes of ECC. Then, as with all CDs, you have the 882 bytes which contain the first and second layer Red Book‑style EDC/ECC and Control Bytes. Mode 2 sectors are primarily used where the absolute integrity of the data is not as important — for, say, audio or animation — so Mode 2 sectors do not have the extra layer of error correction. They do still use the sync and header information, though, so there are 2336 bytes remaining for data.

CD‑ROM/XA (Extended Architecture) discs were developed to allow audio or video to be played back at the same time as computer data. The original Yellow Book CD‑ROMs were designed for storing and publishing data — not for playing audio or video. The format was extended in 1988 with the addition of two new track types — Mode 2, Form 1, and Mode 2, Form 2 — which have a sub‑header field within each sector to describe the sector contents. This makes it possible to interleave Form 1 sectors containing computer data with Form 2 sectors containing audio, video or picture data, all within a single track. Using specialised hardware in the CD‑ROM drive, it is then possible to separate the audio data sectors from the computer data sectors, decompress the audio data and play it back through the CD‑ROM drive's audio outputs, while simultaneously transmitting the computer data to a personal computer for processing or display.

A CD‑ROM Mode 2, Form 1 sector is identical to a CD‑ROM Mode 1 sector, except that the 8 bytes of blanks in a Mode 1 sector have been moved to follow the header information within the sector, and are used to hold the sub‑header information. As with Mode 1 sectors, 2048 bytes are available for the user data (normally computer data which requires the extra layer of error detection and correction provided in Mode 1 sectors).

A Mode 2, Form 2 sector also contains the synchronisation, header, and sub‑header bytes, along with the 4 additional EDC bytes that appear in Mode 1 and Mode 2, Form 1 sectors. However, because the Form 2 sectors are used to hold audio, video or picture data — which doesn't require the high level of data integrity necessary for computer data — the 276 bytes of error‑correction data used in Form 1 sectors are not included, leaving 2324 bytes available for user data.

CD‑ROM/XA discs can be played back on personal computers with suitable hardware and software, and on specially‑equipped CD‑ROM drives or CD‑i players. CD‑ROM/XA was developed as a 'bridging' format between CD‑ROM and CD‑i, and this means that an application designed for CD‑ROM/XA can be made playable on a CD‑i player sharing the same audio and graphics resources. As with CD‑i, you can interleave up to 16 hours of ADPCM‑compressed audio with data, to allow the data to be retrieved from the disc while the audio plays back.

- PHOTO CD

The most well‑known example of CD‑ROM/XA discs are Photo CD discs, Eastman Kodak's digital image storage and distribution system. You can now get your 35mm snapshots supplied as digital files on a Photo CD disc from Boots or other places which process film. Discs can be written to using multi‑session recorders, so the images do not have to be put on the CD disc all at the same time. You can fill part of the disc, take this home, then take the disc back to add your next and subsequent rolls of film, until the disc is full. You can view your photographs at home on your TV screen using a CD‑i player or a dedicated Photo CD player, and you can also read the files on a Macintosh computer using software such as Photoshop.

• KARAOKE CD

Karaoke CD discs are another example of CD‑ROM/XA discs, which you can play on a dedicated Karaoke CD player or on a CD‑i player equipped with a Digital Video cartridge (although CD‑i discs will not play on a Karaoke CD player). Karaoke CDs usually have the word 'Graphics' in small letters beneath the Compact Disc logo, and they feature full‑screen, full‑motion video and CD‑quality audio using the MPEG‑1 compression standard.

- GREEN BOOK

Green Book is the standard for Compact Disc‑Interactive (CD‑i) and is an extension of Yellow Book to allow discs to contain a mix of video and audio, plus data which the user can control interactively, making it ideal for games, encyclopaedias, educational material or business applications. CD‑i discs use Mode 2, Form 1 and Mode 2, Form 2 tracks, which, as with CD‑ROM XA, enable computer data and compressed audio, video or pictures to be played back at the same time.

A CD‑i player looks similar to a CD‑Audio player, but you can hook it up to a TV or a colour monitor and it has a computer inside which you can control using a hand‑held remote. The computer uses a fairly obscure operating system called OS/9, so CD‑i tracks cannot be played on normal CD‑ROM drives. On the other hand, CD‑i players can play audio CDs, CD+Graphics (CD+G), Photo CD, and, with a Digital Video cartridge, Karaoke CD or Video CD discs — a pretty versatile player!

- ORANGE BOOK

Orange Book is the standard for write‑once compact discs. This specification covers both single (Disk‑At‑Once) and incremental multi‑session (Track‑At‑Once) recording. Multi‑session allows you to record a 'session' to part of the disc and then add subsequent sessions at a later date, until the disc is full. A new session will contain a table of contents featuring the old and the new information on the disc, so any CD‑ROM player you want to use to read a multi‑session disc needs to take this into account by reading the last‑written table of contents or directory. Many older CD‑ROM drives cannot read multi‑session discs, so watch out for this. The disc can subsequently be converted to a Red/Yellow/Green book disc by 'Finalising' the session, to add a final Table Of Contents which can be read by any CD‑ROM player.

• WHITE BOOK

The White Book specification was developed to cover the Video CD format, which is supported by JVC and Matsushita as well as Philips and Sony. These Video CD discs are a special kind of CD‑ROM/XA bridge disc that allow you to play feature films and music videos on a dedicated Video CD player, or on a CD‑i player equipped with a Digital Video cartridge. A computer equipped with a CD‑ROM/XA drive, an MPEG‑1 decoder and a host playback application can also be used to play the discs, so they can also be used for computer‑based training applications. Based on the Karaoke CD standard, Video CD features full‑screen, full‑motion video along with with CD‑quality audio, and is independent of broadcast standards such as NTSC and PAL, so (unlike video‑cassette and laser disc formats) a single disc plays on any Video CD platform worldwide.

- BLUE BOOK

Blue Book is the most recent of the 'colouring books' to appear, and this specifies the CD Extra standard, which was developed as a way to include CD‑ROM data on an audio disc. The idea here is that a standard audio CD will give up a little of its space so that you can include a track of CD‑ROM data containing some kind of interactive data related to the audio — which you can play using your computer's CD‑ROM drive and screen. This might be an animated presentation of some aspect of the artist's work, such as expanded sleeve notes, lyrics or music, or just some wildly creative images to accompany the music. Possibly it could be a 'taster' for a full‑blown interactive CD‑ROM version of the album. Also known as Enhanced CD, a CD Extra is actually a multi‑session CD which contains audio tracks in its first session, followed by a data track in the second session. Early attempts to make this kind of CD suffered from the problem that the first track was the data track and could produce a loud clicking in your speakers if you inadvertently tried to play it — despite the large warning stickers on the packaging telling you not to do this! This was all sorted out with the Blue Book standard, so now the CD‑Player will not attempt to play the data track.

All About File Formats

The Yellow Book standard did not specify any file formats, so early CD‑ROM developers had to 'roll their own' — and these were not compatible with each other. Fortunately, manufacturers quickly realized that standardisation was needed, and the International Standards Organisation ISO 9660 file format subsequently emerged. You can create applications for Mac, PC or UNIX systems using this file format, and you can even have application programs for all three platforms on one CD‑ROM, with all three able to access the same set of data files. The problem with ISO 9660 is that it restricts developers to a lowest common denominator in terms of how many characters can be used for the file names, for instance, so this is not so popular any more.

It is perfectly possible to design a CD‑ROM for use with one particular operating system, which lets developers use the full range of features of that operating system, such as long file names, desktop icons and so forth. So, for instance, you can create CD‑ROM discs in Macintosh HFS format which will 'mount' on the desktop of any Macintosh computer, just as though they were disks from any other type of disk drive. These can hold up to 650Mb of your computer files in a read‑only format. Rewritable CD machines are beginning to appear, but these are not commonly in use as yet, so you will mostly encounter discs which can only be written to once.

Hybrid discs — which will work with Mac and PC — are also very popular, as you might imagine. You can create a CD‑ROM with both Mac HFS and ISO 9660 file systems which share the same data and can be read on both Mac and PC. This solves the problem of having to produce a Macintosh‑specific CD for Macintosh users and an ISO 9660 CD for PC and UNIX users.

You can also mix audio and computer data on one disc in various ways. Originally, a mixed‑mode CD would consist of one data track and several audio tracks, with both data and audio written in one session. The data track would always be placed in track 1 — just in front of the audio tracks on the disc — which was a problem, as I mentioned earlier, since the data track would produce clicks in the speakers if inadvertently played on an audio CD player. This mixed‑mode format has largely been superseded by an audio/data multi‑session format where the first session consists of audio tracks and the second session consists of data. Another twist in the tale is that this second session data can be in CD Extra format, or in HFS or ISO 9660 XA formats, or in Mac/ISO Hybrid XA format — which makes the format even more versatile!

As you may already have gathered, a multi‑session disc is so‑called because you can write one set of data to fill part of the disc, and then write one (or more) additional sets of data to fill the rest of the disc. These sessions are linked together in such a way that only one logical device appears when the CD is mounted. However, not all CD‑recorders can record this type of CD and not all CD‑ROM drives can read them.

A 'multi‑volume' CD also consists of multiple sessions, each recorded at a different time, but, in this case, each of the sessions is completely independent of the others. When this type of CD‑ROM is mounted on your computer's desktop, each session will appear as an individual logical 'volume'. In other words, if you put two sessions on your CD‑ROM in, say, Mac HFS format, when you put this into your Mac's CD‑ROM drive, two icons will appear on your desktop, each representing one of these 'volumes' of data. These look and behave just like hard disk icons, except that there is a small locked padlock in the top left‑hand corner of the window which appears when you open either of these volumes onto your desktop. This indicates that the disc is read‑only. Again, not all CD‑recorders can record this type of CD, and not all CD‑ROM drives can read them. Finally, it's worth noting that Mac HFS CD‑ROMs can only be multi‑volume rather than multi‑session.

Disc‑At‑Once VS Track‑At‑Once

When you're buying a CD recorder it can be important to check whether it's capable of recording in Disc‑At‑Once mode if you want to write discs to master from, because some CD‑recorders can only write using Track‑At‑Once mode. With Disk‑At‑Once recording, the whole disc is written in one pass without turning off the laser, while Track‑At‑Once mode only allows you to write one track at a time. When you use Track‑At‑Once mode, the laser will stop writing between each track, but the laser beam doesn't turn off immediately, so a couple of sectors are allocated at the end of each track which will be wasted as the laser shuts down. These are called the 'run‑out' sectors and account for the fact that Track‑At‑Once recorders have a fixed track spacing of 2 seconds. With Disc‑At‑Once mode, no run‑out sectors are generated between tracks, so the pause between each track can be of any length, and songs can even be run together with no gap.

Note that if you're making audio CDs to be commercially produced, the run‑out sectors created in Track‑At‑Once mode may be considered as unrecoverable 'E32' errors when the disc is checked at the pressing plant, and the disc may be rejected as unsuitable for pressing from. This situation is changing, though. Reportedly, Doug Carson Associates, who provide glass mastering and format‑transfer software to pressing plants, have solved the problem. DCA's latest software version apparently checks the TOC on the CD‑R to find out where the gaps are, and whenever it finds E32 errors there (generated by the laser turning on and off between tracks) it replaces them with digital silence. So, unless you have CD‑Rs with E32 errors in places other than the gaps between tracks, pressing plants using the latest DCA software will not reject CD‑Rs made using Track‑At‑Once mode.

About The Books

- System Description Compact Disc Digital Audio (Red Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- System Description Compact Disc Read Only Memory (Yellow Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- System Description Compact Disc Read Only Memory Extended Architecture (Green Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- System Description Compact Disc Systems Part II: CD‑WO (Orange Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- Update to System Description Compact Disc Systems Part II: CD‑WO (Orange Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- System Description Compact Disc Bridge (White Book), NV Philips and Sony Corporation.

- ISO Standard 9660: Information Processing — Volume and file structure of CD‑ROM for Information Interchange.

- For more information on the Book standards, contact the following address:

American National Standards Institute, 1413 Broadway, New York, NY 10018. Tel: 001 212 642 4900.

Sub‑Codes

Each sector on an audio CD contains control bytes identified by the letters P through to W. These are often referred to as sub‑channels or sub‑codes, and the most important are the first two — the P and Q sub‑codes which you may have seen referred to in this magazine before.

For instance, in the Lead‑In area, the Q sub‑code contains the Table Of Contents, while in the Program area of the disc the P sub‑code contains information about where the music starts and ends, and the Q sub‑code contains absolute and relative time information.

The other sub‑codes, identified as R to W, are not always used, but it is perfectly possible to store additional information in them. An early extension of the basic CD format, called 'CD + g', used these bits to add graphics and MIDI data for each track, and some specialised CD + g players were produced which had video and MIDI outputs. These were never available in the UK, as far as I am aware.

There are various other codes which can be set for CD discs and which you need to be aware of. For example, if you want to make sure that all the rights‑holders get paid when your disc is broadcast, you should be including an ISRC code. This is the International Standard Recording Code which can be assigned to each and any final mix to uniquely identify this mix. The code can then be used, along with records kept by the record companies, royalty‑collection organisations and rights organisations, to track the owners and rights‑holders who should be paid when the recording is broadcast publicly or exploited commercially.

If the disc is released commercially, it will almost certainly include a Media Catalogue Number, which is a unique identification number for the CD in the form of a UPC or EAN bar‑code. These code numbers are allocated by the EAN or UPC authorities and consist of 13 consecutive digits which are allocated by one of these organisations.

Older DAT and other digital recorders sometimes used a system of 'pre‑emphasis' on recorded material, with a corresponding 'de‑emphasis' on playback. Pre‑emphasis boosts the high frequencies prior to A/D conversion, while de‑emphasis removes the boost after D/A conversion. De‑emphasis circuitry is built into all CD players to provide compatibility with any material recorded using pre‑emphasis. However, the emphasis bit must be set to 'on' in the track's Q code so that the CD player will know that it should use the de‑emphasis circuitry while this track plays back.

Each track on a CD has a Copy Prohibit 'flag' bit setting in the track's Q sub‑code, to indicate whether copying the track is allowed. This Copy Prohibit bit was originally intended to prevent direct digital copying using DAT recorders, but virtually no recording equipment uses this today, so it has no effect in practice. Subsequently, the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS) was developed to prevent users from making a digital copy of a digital copy. In this system, the SCMS 'flag' bit is incremented when the source material is digitally copied from one digital recording device to another, so you're allowed to make one digital copy of the source material using SCMS‑equipped recorders, but you won't be able to make any further digital copies of that recording.

Checking this 'flag' on any CD tracks before you write the CD identifies these tracks as the first copies, so you won't be able to record them digitally from the CD onto an SCMS‑equipped digital recorder. If you want to allow digital copies to be made, don't set the SCMS flags on the CD. Then, if you use an SCMS‑equipped recorder to make a copy of the CD, it will be the first digital copy and will have the SCMS flags set for each track by the system built into the recorder. Now if you try to copy that recording digitally, SCMS will prevent you.

By the way, just in case you were wondering, checking SCMS will override the setting for Copy Prohibit.