Spoiler: Santa Claus and the Invention of Childhood

How St. Nick went from “beloved icon” to “beloved lie”

Every year, a significant portion of adults in the U.S., and a significant number of them around the world, get together and, spurred by some combination of love and whimsy and magical thinking, engage in a massive lie. Santa Claus, a.k.a. St. Nick, a.k.a. the bearded old man who embodies childhood: He is a spoiler in every sense of the word. He showers children with gifts, yes, but he’s also a wide-scale deception that puts the paternalism in “paternalistic lie.” He’s one of those phenomena, like reality TV and Donald Trump, that brazenly blur the line between fact and fiction. (Slavoj Žižek described him as a ritual in the guise of a myth—a mass self-deception that implicates everyone who participates in it.) And Santa does all that, of course—he being what he is—because people let him.

Future generations, learning about the annual fealty so many people pay to an obese, elfin home-invader, may well look upon all the attendant stockings and stories and shake their heads in confusion. “Why did they do that?” they might wonder. And, seriously: Why? Why do so many engage, cheerfully, in this annual, widespread deception? Why do they make so many exceptions—when it comes their attitudes about materialism, when it comes to their attitudes about truth itself—for Santa? Is it to preserve a sense of childhood as a sacred space? Is it because, even in an age obsessed with spoilers and fact-checking, an age of Facebook and Snopes and Siri and Google, this particular non-fact is somehow acceptable? Is that why kids who know the truth, either because their families don’t participate in the ritual or because they’ve aged out of it, keep the secret for everyone else? Is it why institutions from the U.S. Postal Service to NORAD to the White House to your local mall to pretty much every pop-cultural product of the past century have enthusiastically lied to your children?

I have so many questions. They come down, however, to just one: Why? Why do people Santa?

* * *

First, the Santa myth itself. There are, best I can tell, three general assumptions that have survived today to explain the origins of Santa as a Christmas icon. One is that his imagery is based on St. Nicholas, the fourth-century Bishop of Myra. Another is that he was introduced, as a commercial figure, in ads for the Coca-Cola company in the early-20th century. Another is that he’s a tale as old as time—that the current manifestations of Santa are iterations of a figure who’s been part of Western culture for as long as that culture has involved rooftops and reindeer and Christmas trees.

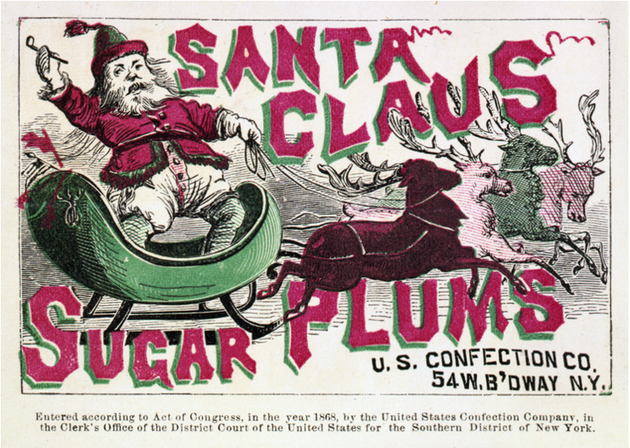

Those are all, like Santa himself, simultaneously true and not-true. The figure we know today is certainly an extension—you might even say a camp version—of St. Nicholas, but he is also influenced by similar, loosely Christmasy figures across Western cultures: Sinterklaas (Dutch), Père Noël (French), Santa Lucia and Jultomten (Swedish), Babushka (Russian), Christkind and Knecht Ruprecht (German), Befana (Italian), and the Roman god Saturn. Visually, however, the main precursors to the fur-wearing, rosy-cheeked figure we know today, in the U.S. and now in many other countries, are images that were produced long before Coke came along—paintings created by the 19th century cartoonist Thomas Nast. Published in Harper’s Weekly between 1863 and 1886, the images, as the professor Russell Belk puts it, “showed Santa as obese, Caucasian, white-bearded, jolly, dressed in rich furs, and as the bearer of abundant gifts of toys.”

Santa had previously appeared in Harper’s; a sketch in an 1858 issue, The New York Times notes, depicts him beardless, riding a sleigh that’s pulled by a turkey. Nast’s paintings, however—and similar ones that would follow in the next century, created by Norman Rockwell—drew heavily from the other thing that influenced Santa as we know him today: Clement Clarke Moore’s “A Visit From St. Nicholas,” widely known today as “The Night Before Christmas.” The poem itself had been influenced by the writings of Moore’s friend Washington Irving, and by Charles Dickens; it was published (anonymously, in the Troy, New York Sentinel, in 1823) during a time that found Christmas Day overtaking New Year’s Day as the primary holiday of the season. And during a time that found Americans renegotiating the meaning of that holiday. Together, the poem and its post-facto illustrations helped, Russell Belk argues, “to secularize the image of Santa Claus by dropping the religious symbols of the European figures—mitre, staff, and bishops’ robes.”

The Santa emerging in the mid-19th century was plump and jolly and kind: a fitting image for the age of relative plenty being brought about by industrialization. He was grandfatherly. He was also, ironically and maybe fittingly, connected to other images of the time: Nast’s drawings of Wall Street’s wealthy. Santa, who with his heft and his rosiness and his rich furs was a visual symbol of economic prosperity, was appropriated not just from Christian tradition, but from Gilded Age acknowledgements of capitalism’s forces, and from Gilded Age anxieties about inequality. Those—via Coke, via Hollywood, via American optimism that can easily veer into American forgetfulness—would soon fade. He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf … and we laughed when we saw him, in spite of ourselves.

So that’s the image aspect of things: the figure of Santa, an amalgam of the religious and the commercial, of the ancient and the modern, of the magical and the industrial. But what about Santa as a ritual? When did St. Nick become not just a figure, but a mythical-magical gift-giver? When did he make the leap from “beloved icon” to “beloved lie”?

Culture being what it is—occasionally awkward, often chaotic, and above all decidedly not monolithic—it is hard to pinpoint when, exactly, Santa became a full-fledged home invader. What is clear, though, is that his status as a participatory myth is a relatively recent invention: It came about, like the fur-and-reindeer images, in the 19th century. Santa, it seems, arose with industrialization, with the economic plenty that came with it, and with something else prosperity inspired: changing notions about the family and the children’s place within in. Santa, as we know him today, was born during a time that was rethinking and reimagining and in many ways reinventing that oldest of things: childhood.

In his book The Battle for Christmas, the professor Stephen Nissenbaum traces the origins of the Santa lie to a particular decade: the 1820s. He examines the voluminous correspondence of the Sedgwicks, an affluent family whose members were scattered across New York and Massachusetts. In 1823, Moore published “A Visit From St. Nicholas.” By 1827, Nissenbaum notes, Robert Sedgwick and his wife Eliza mentioned in their correspondence that they had hung stockings in their home so that “Santa Claas” could visit their children; by 1829, the stocking-stuffing ritual had extended to the Massachusetts branch of the family. By 1834, a young Sedgwick was writing to her aunt, the writer Catharine Maria Sedgwick, “I hope ... that Santa Claus has given you at least as many presents as he has me, for he only gave me four.”

Around this time, Santa—in text and in image, reflective of Moore’s “right jolly old elf”—began to spring up in advertising, as well. And not just, in the Coca-Colan model, as a spokesman. In 1841, the first popular image of Santa appeared in a commercial newspaper; that same year, a candy store in Philadelphia used a life-sized model of Santa to entice customers. A paper of the time reported on the stunt, calling the model “so lifelike that no lad who sees it, will ever after accuse ma or pa of being the Kriss-Kringle who filled his stocking.” It added: “That such a person exists will be fixed indelibly on their memories.”

That such a person exists. Indeed. And the memory-fixing, from there, happened quickly. (As Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace put it in Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, “New Yorkers embraced Moore’s child-centered version of Christmas as if they had been doing it all their lives.”) Santa-centric ads proliferated, and so, with them, did Santa-centric Christmas celebrations. By 1857, a New Bedford whaling wife named Mary Chipman Addison was remarking of a holiday spent aboard her husband’s whaleship with her daughter, Minnie: “Christmas Day reminds us of home and friends. Minnie wished to hang up her stocking as usual, and as I had a tin of candies which her grandpa put up for her, Santa Claus managed to fill it very well.”

One reason the right jolly old elf may have caught on in homes (and ships) as well as ads, Stephen Nissenbaum suggests, is that he offered something that was particularly appealing to parents of the time: gift-giving that could pretend not to be gift-giving. The 19th century, like our own, had deep anxieties about the commercialism creeping into Christmas. “Even more than today, the exchange of Christmas gifts in the 1820s and ’30s was a ritual gesture,” Nissenbaum notes, “intended to generate the sense that sincere expressions of intimacy were more important than matters of money or business.”And yet—the paradox of Christmas—gifts are generally very much matters of money and business. Santa, the most intimate gift-giver of them all, offered a way for parents to participate in that ritual without expressly participating in it. He allowed parents to indulge their children while outsourcing all the indulgence. He was a figure fit for a time that had concluded, as Little Women goes: “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.”

The sociologist Warren Hagstrom argued that Santa is something even more particular, too: a father figure. One who allows fathers to nurture and show affection to their children without compromising their status as disciplinarians. This, too, might help to explain Santa’s quick explosion in popularity. The mid-1800s, Nissenbaum points out, was a time that was rethinking the notion of childhood as a distinct phase of life. In the U.S., in particular, parents were negotiating between Puritan ideas of child-rearing and more progressive and inclusive ones. Spare the rod and spoil the child was giving way, under the influence of Johann Pestalozzi and Unitarianism and the new middle class and Victorian-inflected notions of the sanctity of the family, to something more permissive: Simply, spoil the child. Santa helped to ease that transition. He converted parental devotion into physical objects—by way of seasonal magic.

And! He converted parental judgment into those objects, too. In 1833, one of the Sedgwicks—Elizabeth Dwight Sedgwick of Stockbridge, Massachusetts—published a short story in the gift book The Pearl. It was subtitled “The Christmas Box,” and it featured Santa giving children not gifts, but rather poems that, with sternness but also affection, pointed out their character flaws. It proved hugely popular. Nast’s images of Santa, too, included the old man’s “naughty or nice” list. “Theologically,” Nissenbaum has put it, “Christmas functioned in part as a children’s version of judgment day.” Parents—wanting to discipline, not always wanting to be the disciplinarians—took advantage of that. Santa was a perfect scapegoat.

In that, the commercial images and religious iconography and dramatic character collided: Here was a figure—reindeer, fur, elves, “Saint”—who seemed to speak to an older time, a simpler time, a more magical and mystical time. Here was a figure who seemed to speak of the things Americans who were experiencing the pangs of social upheaval were craving above all: the warmth and reassurance of tradition. That he was essentially a contemporary invention did not much matter; he suggested, in everything he did and claimed to be, nostalgia.

“Santa Claus represented an old-fashioned Christmas, a ritual so old that it was, in essence, beyond history,” Nissenbaum notes. People knew, of course, that he was not real. “But in another sense they believed in his reality—his reality as a figure who stood above mere history. In that sense, it was adults who needed to believe in Santa Claus.” Or, as Pestalozzi put it back in the early days of the modern Santa, to parents and children alike: “Let this festival establish you in the holy strength of a childlike mind.”

Today, childhood is both longer and shorter than it used to be. Today, too, mystery is harder to maintain, not just because cynicism is a common cultural attitude, but because so many of us navigate the world with the help of omnipresent machines that will answer, or try their best to answer, whatever question may pop into our minds. We live, essentially, in Santa-challenged times. We live in times that make it harder to lie, to ourselves, and to each other. And yet that might be even more reason—it was adults who needed to believe in Santa Claus—to keep St. Nick alive. Maybe the moment calls for some magic. Today, I asked a question: “Siri, is Santa real?” She replied, “Well, those cookies don’t eat themselves.”