Dalmatia

Born in 1908 in central Dalmatia, CVITO FISKOVIĆis the director of the Historical Institute of Dubrovnik and a member of the Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences in Zagreb. He has participated in international congresses of historians of art and curators of monuments and has lectured in England, France, and Italy.

ONE of the most beautiful and interesting elements in Yugoslav history and culture is Dalmatia, the sunny southwestern gate to Yugoslavia. There is a harmony between the rugged mountains under the Mediterranean sun and the azure sea; between the numerous layers of civilizations, dating from the first millennium B.C. to the present day, and the manifestations of a Slavic culture with its western European forms.

The earliest inhabitants were three IndoEuropean Illyrian tribes of shepherds and land tillers: the Ardeans, who displayed a capacity for organization of a state in the third century B.C.; the warriors and freedom-loving Dalmatians, who for a long time resisted the Roman conquest and after whom this province is named; and the skillful sailors and pirates, the Liburnians, from whom the swift Roman ship the Liburnian galley acquired its name. Greek merchants traded with these illiterate Illyrians, and during the peaceful contact between them the Greeks founded in the fourth century B.C. a number of colonies, on both the shore and the islands. Some of the present-day place names in Dalmatia, such as Vis, Korčula, Hvar, and Trogir, are derived from the original Greek names, Issa, Corcyra, Pharos, and Tragurion. This peaceful coexistence lasted from about the fifth to the first century B.C., and there are many remains which testify to the intercourse; the tastefully decorated Greek vases, the elegant Tanagra statuettes, and the artistically minted coins of Pharos, Corcyra, and Issa, which demonstrate that a lively trade did exist, partially protected by the Cyclopean forts. But this growth of artistic refinement was cut short by the conquest of the Roman Emperor Augustus in the first century B.C.

Dalmatia became a Roman province, and the Pax Romans of Augustus led to the establishment of Roman colonies, which grew peacefully. Roman civilization and the Latin language spread fast over the new roads, which, together with the Roman sailboats and the fast triremes, brought Dalmatia closer to the urbs and made it a part of the unified Roman world. The Roman dominion lasted until the period of great migrations of European peoples in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., and the ruins of Roman cities such as Salona, Jader, Narona, and Epidaurus are remnants of the Roman domination. One can still see their city walls, streets, and squares, with fragments of decorated buildings, as well as some villae rusticae close to the springs and the seashore. Among these, one of the most distinguished is the urban complex of Salona, now in ruins, with its walls, amphitheater, baths, and basilicas. In its immediate surroundings was the monumental palace of Diocletian, the great reformer from the beginning of the fourth century. It is within this palace that in the course of centuries the largest city in Dalmatia, Split, developed. There one finds a mausoleum of the Emperor, which in the seventh century became transformed into the cathedral of the medieval city. Also, one finds a temple of Jupiter, which was later to become a Christian baptistery, as well as the huge and elegant columns of the peristyle and the solid walls with towers and arcades. Side by side are buildings in the Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance styles.

During their rule over Dalmatia, the Romans brought with them change and luxury. They spread a new religion and new customs, built lavish theaters, long aqueducts, houses decorated with mosaics, temples with gigantic sculptures, tombstones with realistic portraits of the deceased, and tombs in which are found tastefully executed artifacts. Next to the artistic objects imported from the Apennine peninsula one may find indigenous Dalmatian creations, which by their rusticity as well as their inscriptions reveal traces of the old Illyrian and Greek heritage.

The troublesome changes in Roman political life did not spare this province. Close to these wooded islands some of the sea battles between Caesar and Pompey took place. In the amphitheater of Salona, the Christian martyrs bled. And even after the fall of the Western Roman Empire toward the end of the fifth century A.D., Dalmatia was ruled by a Roman Emperor, Julius Nepos. Only after his death did this province fall into the hands of the Germanic King Odoacer and acknowledge the ruler of the Ostrogoths, Theodoric.

Next followed an occupation by the Byzantine Empire, yet the glow of Justinian’s civilization could not re-establish prosperity in the impoverished land which from the seventh century was settled by the Slavs. Since the new Slavic tribes had no use for monumental architecture, most ol the Roman decoration fell into ruins. Yet the skillful farmers lived in Roman settlements, took good care of the fields, and penetrated into deserted cities. These Slavs joined the small Roman population which did not escape and from them accepted Christianity. With a fresh approach they started building a new, Slavic civilization on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. Their culture had none of the Roman plans for conquests, nor a developed taste for comfort, which the Romans and the Byzantines had displayed. Therefore, this new culture was neither monumental nor dramatic, but miniature and simple.

Here on the seashore, in central and northern Dalmatia, the Croats founded in the ninth century a state which resisted the Frankish armies, maintained friendly contacts with Byzantium, and became an independent kingdom, the Kings of which, in the eleventh century, had their crowns conferred by the Roman Pope with the title “rex Croatiae et Dalmatiae.” The southern part of Dalmatia became a part of the Serbian state, and thus both south Slavic peoples affirmed their claims on the coast, from which their men-of-war swung all the way to the fertile coast of southern Italy. They now became the makers of history in this part of the Balkans.

Their church architecture varies from vaulted and centrally oriented buildings to basilicas with three naves. In addition, it is distinguished by shallow pre-Romanesque reliefs and frescoes, of which those in the church of St. Michael in Ston, from the eleventh century, are among the oldest examples. In architecture, sculpture, and painting one can find the expression of the bold, although somewhat primitive, freedom of the local masters, who transformed and freely interpreted the artistic models of late antiquity, of western European pre-Romanesque art, and of Byzantine art.

The independence of Croatia was weakened by internal discords, leading to two successive occupations of Dalmatia, first by the Hungarians and then by the republic of Venice. Thus, from the twelfth century onward, the Croats lived within the political framework of these two expansionist states.

IN SPITE or foreign domination, the medieval cities of seamen, merchants, and craftsmen acquired their autonomy and became fortified settlements, and even in the thirteenth century were built according to urbanistic principles. The wealthier citizens, following a European model, assembled in city councils and established hereditary rule, thus founding in the thirteenth century families of nobility. These small and free communes proclaimed their own city statutes, chose their own patron saints, leaders, and bishops, minted coins, negotiated trade agreements with rulers in the Balkan hinterlands and with the Italian communes, and even established miniature defense alliances. They were small states which fought for their fields and their salt pans. Although they were dressed in the newly woven clothes of the Roman civilization, in their family names and their language the Slavic element predominated.

These city-states prospered in spite of internal dissensions and struggles with their immediate neighbors. In time they built squares and harbors, Romanesque town halls and cathedrals, which they decorated with fantastic sculpture and artifacts of gold and silver, acquired in abundance from medieval Bosnia and Serbia. In this cultured environment there were sculptors with Croatian names in the century of Dante: Buvina, who carved the figured relief on the monumental cathedral gates in Split; and an even more talented artist, Radovan, who, on the portal of the cathedral in Trogir, working with a skill equivalent to that of his contemporaries in Italy, carved rich and harmoniously interwoven scenes from daily life — lively children, hunters in motion, and animals on the run. This same liveliness in narration may be found among the writers of the old chronicles. Archdeacon Toma of Split and the anonymous priest from Bar referred to as “Priest Dukljanin.” The growth of medieval Dalmatian communes manifests itself in innumerable written documents preserved in archives and in legislation, which in the fourteenth century existed in the Croatian language, even for small villages in these stony mountains.

In order to safeguard its mercantile naval routes to the Levant, the strongest power on the Adriatic Sea, the rich and bellicose Venetian republic, bought these communes from Ladislas, the pretender to the Hungarian throne, and occupied them in the fifteenth century. Yet, in spite of an occupation which lasted more than four centuries, Venice did not succeed in erasing the ethnic distinctions of Dalmatians, who went to Venice in order to print there in the Slavic language their prayer books, their poems, and the Renaissance dramas by Dalmatian writers and humanists. At the same time, at home around their fireplaces they sang, accompanied by the one-stringed and bowed musical instrument gusla, melancholic poems about heroes from the past or about a mother’s feelings for her children.

The Slavic population of Dalmatia grew in strength even more when, after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Turkish Empire conquered the divided medieval states on the territory of present-day Serbia and Bosnia. Refugees came from the destroyed cities to the fortified coastal cities, and thus new blood refreshed the old population, worn out by the plagues and crusades. In those critical years, the Dalmatian coast was saved from the Turkish avalanche not so much by Venetian arms as by its own heroism, and in the case of the republic of Dubrovnik, by its keen diplomacy, through which it not only maintained but strengthened its independence.

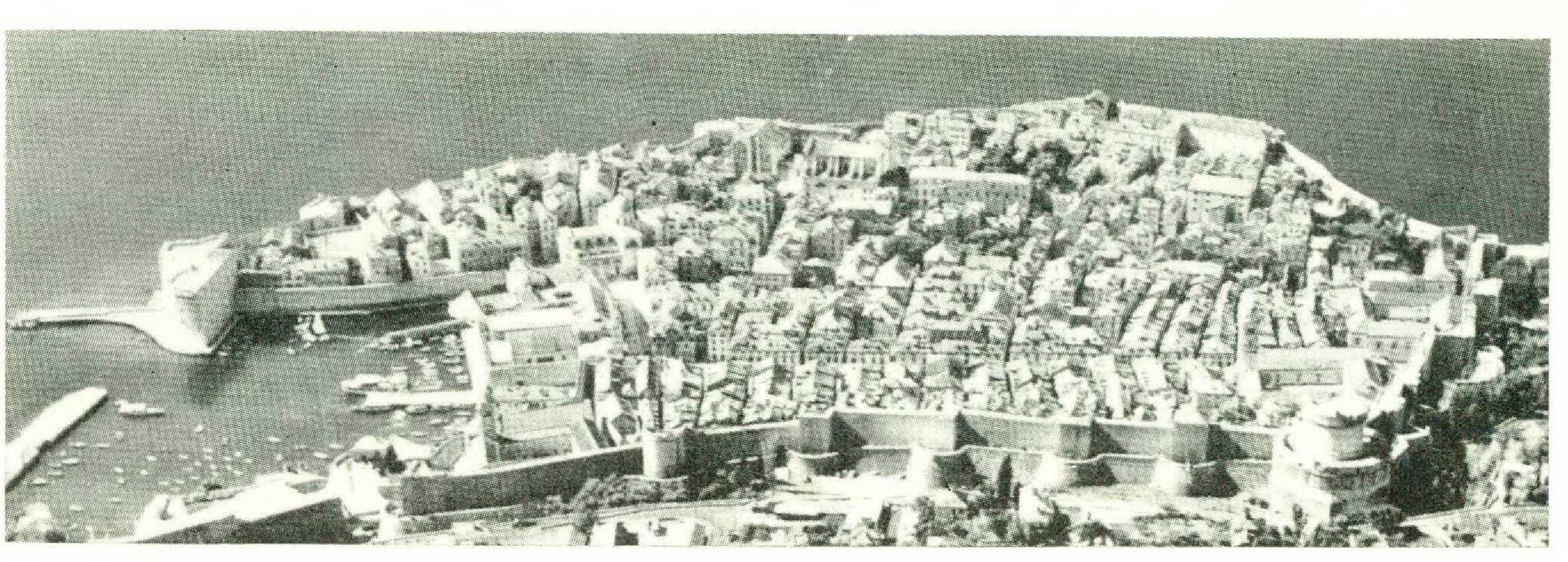

THE old city of Dubrovnik, which in the ninth century resisted a siege by Arabs and in the fourteenth century managed skillfully to liberate itself from the protectorate of Venice, gradually formed its own aristocratic republic. Its independence was growing through its trade with the hinterlands and overseas. Already, in the thirteenth century, Dubrovnik had founded some of its trade outposts in the crossroads of some important Balkan traffic routes, and later, in the seventeenth century, Dubrovnik established its consulates in various Mediterranean ports. When circumstances required, Dubrovnik negotiated with Hungary for protection, and later, without invoking papal wrath, with Turkey. And Dubrovnik succeeded, by paying annual dues, by bribery, and by the skill of diplomatic whispering, without an army or war, in maintaining itself longer than its centuries-old rival in the Adriatic, Venice, up to the time of Napoleon’s conquest. Though the citizens of Dubrovnik built, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, thick walls and fortresses, no blood was ever spilled on these stones, and no cannons ever damaged them.

Under the constant vigilance of Dubrovnik diplomacy, which extended from the Vatican to El Escorial, from the city of Buda in Hungary to the Moscow Kremlin and Istanbul the republic of Dubrovnik grew quite rich. It was there that for several centuries the Slavic culture, art, and literature manifested itself more luxuriantly than in other parts of the conquered Balkans. The flags of its ships and its silver coins carried the motto Libertas, and on its largest fortress, as well as around the loggias of the comfortable and luxuriously decorated Gothic and Renaissance homes, may still be read the mottoes of the Dubrovnik nobility: Non bene pro toto libertas venditur auro and Pax optima rerum. And these were no empty or hollow phrases, because this small republic proved, by guarding and stressing its neutrality over the course of centuries, that it could truly live in peace and guarantee daily bread to its craftsman, vintage to its wine grower, and freedom of navigation to its sailor. That is why one of the many poets of Dubrovnik recommended to the European rulers of the sixteenth century in the Slavic language:

By injustice divide states with bloody arms?

He protested in the Vatican and in Istanbul against wars and carnage, which the Dubrovnik people, living on the border line between Islam and Christendom, experienced more frequently than many of the more learned peoples of Europe between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries.

Taught by the past, Dalmatians inherited a feeling of resistance toward all foreign conquerors. They sought only to continue to create and express themselves in their own language under the southern sun.

That sun which fertilizes even this stony karst and is reflected in the azure of the crystal-clear sea, that same sun seems to have filled a number of talented people with the restless feeling of creativity. Here in Dalmatia were born the Romanesque sculptors Radovan, Buvina, and Michael from Bar; Juraj the Dalmatian, who in his own land, as well as in the Papal State, built in the fifteenth century significant works of sculpture and architecture; and four centuries later, Ivan Meštrović, whose sculptures decorate a church in South Bend, Indiana, and squares in Chicago, Split, and Trogir. The still living sculptor Franjo Kršinić also is internationally famous, as are numerous other artists.

Dalmatians were accustomed to receiving artistic models from southern and northern Italy, to reading books written in the Beneventan script from Monte Cassino and decorated with miniatures of the school of Bologna, to writing and translating poems into classical Latin, to bringing into their churches works of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese, and into their palaces Venetian furniture of the baroque and rococo periods, and to having portraits painted by Titian, Lotto, and Palma the Younger. Yet Dalmatia cultivated its own artists, who formed special schools of painting and architecture in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Only when this province was under the pressure of war between the Venetians and the Turks did the artists and scholars go abroad and contribute to the development of Italian and other cultures. Active in neighboring Italy were the refined sculptor and portraitist Francesco da Laurana and architect Luciano da Laurana; the passionate sculptor Nicolo dall’ Area; the spreader of the Renaissance in the valley of the Danube and builder of papal tombs, Ivan Duknović; as well as the painters Medulić (Meldola), Culinović, Benković, painter of miniatures Julio Klović (Giulio Clovio), and other artists who were called Schiavoni, thus designating their Slavic origin. The physicist Marco Antonio de Dominis, whom Newton mentioned in his Optics, became prominent in the course of the seventeenth century in Italy, France, and England; and in the eighteenth century the astronomer and mathematician from Dubrovnik, Ruggiero Bošković. who with his theories about atoms foreshadowed present-day atomic science, acquired worldwide fame.

THE decline of Dalmatia began during the period of the wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The pathetic shimmer of the baroque did not disturb the old and medieval environment. The cities were still fortified with bastions modeled after Vauban’s, yet the youth from impoverished villages, instead of learning crafts, were forced to become Venetian soldiers and Turkish janissaries. In those centuries there was no longer such a powerful artistic creativity, and artifacts were purchased in Venice, Ancona, and Apulia and paid for by cash acquired in trading with the Turkish caravans.

Although an earthquake in the middle of the seventeenth century severely damaged the stonewalled city of Dubrovnik, its merchants remained first-rate traders. Diplomatic contacts were maintained, and the solidly built ships of its fleet continued to transport grain and other merchandise. The merchants transported mainly foreign products, because their own agricultural and manufactured articles were insignificant. They continued sailing in the eighteenth century with their 300-odd sailing ships. They started crossing the Atlantic Ocean, and in the second half of that century they frequently came to the United States, whose liberation they viewed sympathetically. They saw it as a useful opening of new and free markets.

During the American struggle for independence, the Dubrovnik merchants gave to their sailing ships such names as America and Postiglion d’America. Because of the respect for the great sea power of England and its allies, the cautious and conservative republic of Dubrovnik was hesitant to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Congress, although it was urged to do so by its foresighted consul in Paris, Franjo Favi. In 1778, when Benjamin Franklin succeeded in the establishment of an alliance with France against the English, Favi wrote several reports about America and was finally authorized to convey Dubrovnik’s greetings to the American representatives in Paris. I quote here from a report of his visit:

The independence of the United States of America is finally recognized by all. The American representatives have already received information that the Congress gave approval for the preliminary negotiations for peace, and they have started paying protocol visits to foreign diplomats who reside here. According to the custom, these visits were returned. According to your instructions I visited them also, and after I conveyed to them the greetings of Your Excellencies, I recommended to their attention the ships of die citizens of Your Republic declaring that they too wish to enjoy the benefits which American independence and freedom are opening for Europe. They were pleased by these remarks and told me the sailing ships of Dubrovnik may, as all other ships, enter American ports with assurances that they shall be cordially received and that they will be extended all the facilities given to ships of other nations. . . . If some Dubrovnik sailing ship leaves for the United States of America (because that is now the name of the thirteen provinces which for the sake of liberty became united into a confederation and are no longer called bv the detested term “colony”) and if Your Highnesses would wish on such an occasion to write to the Congress and ask for help and facilities which may rightfully be expected from a free and generous nation, that would be all to the good. The American representatives have even assured me that such a message would be very pleasing to the Congress.

With this official visit of its consul to the American representatives in Paris. Dubrovnik, the only free state among the south Slavs, gave the United States of America a recognition de jure. It may be added that in the seventeenth century a Dubrovnik poet, Djono Palmotić, in his ballet Colombo and in Croatian verse mentioned that there were sailors from Dubrovnik in Columbus’ crew.

The consul Favi, in another of his letters to the government of Dubrovnik, forecast the future of the United States, as he was reporting about the great numbers of western Europeans, especially Germans, who were emigrating to America. Here are some excerpts from that report: “Emigration should open the eyes of rulers whose governments do not pay attention to the growth of trade and agriculture. If they do not apply a better system, the population of their states will diminish and America will partially owe its growth to the poor European governments. . . . There are all indications that that country may become the strongest country in the world.”

Knowing the activity of the Dubrovnik merchants and sailors, the government of the United States tried to conclude a treaty with the republic of Dubrovnik, and in 1790 the American representative in Madrid, William Carmichael, frequently met the outstanding Benedictine monk from Dubrovnik, Anselm Antica, at the lavish dinners in the Spanish royal palace. Carmichael expressed to him the desire to suggest to the government of Dubrovnik the conclusion of a treaty with the newly founded republic. Antica informed the senators of Dubrovnik about this and suggested that they follow the example of their ancestors, who had earlier concluded a treaty with the Turks before they came to Europe, and that there should be no reason not to conclude a treaty with a new and forward-looking state across the ocean. Although the conservative government of Dubrovnik hesitated, the white flag of Dubrovnik was seen more and more frequently at the end of the eighteenth century in American harbors, and American sailors could at the time of their own struggle for independence very well understand the inscription on that flag, Libertas.

Changes took place in Dalmatia. Those who were forced by poverty to emigrate to North and South America at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of this century sometimes return to refresh memories of a childhood spent in the semidarkness with smoky fireplaces. Yet, in their reconstructed villages they find, instead of fire and embers, electric and gas appliances. Tractors take the place of oxen, and the melancholic bowing of guslas is giving way to the loud songs of distant lands on the radio. The young people seldom ride donkeys on the slippery narrow passageways or sail in the windy channels between islands. Buses and motorboats carry them to the cement and bauxite factories and to the shipyards in which fast transatlantic motor ships are built for Denmark and Argentina, for Poland and the United States.

The cities are being rebuilt, and skyscrapers surpass in height the medieval belfries. Sandy beaches are surrounded with modern hotels made of prestressed concrete in contemporary architectural designs. New asphalt roads curve through forests of dark cypresses and silvery olive trees, bringing the driver to high villages filled with white stone roofs and overlooking the sea. In that wilderness in which the superstition and tales of former centuries placed fairies and witches, today one hears the hum of hydroelectric power stations, and the abysses are crossed by highvoltage transmission lines.

Less and less do the girls wear their beautifully decorated folk costumes, which accentuate their beauty, especially in the landscape of Konavle and by the waterfalls of Kerka. The lace from Pag and the embroidery from Vrlika are not produced in such quantities as before. Old mills have disappeared along with the typical village houses and folk dances. The mountaineers leave their villages and come to the shore.

But the fishermen are still building their boats, and the almond and orange trees, olive trees, and vineyards are still being planted on the terraced sunny slopes. In the quiet bays and the sandy shoals, shells, praised so long ago by Renaissance travelers, are even now being cultivated.

The Arcadian peace, the mythological beauty of Dalmatia will not be lost; neither will its sons be lost in the fast rhythm of present-day life, nor will those be lost whose calling it is to see that this cradle of south Slavic medieval and Renaissance culture, art, and letters achieves a harmony with the progress which no nation can bypass.

Translated by Miloš Velimirović.