Live fast, die young: it could so easily be a futurist slogan, the kind of injunction these Italian artists liked to scream out loud across dozing city piazzas. Kill the moonlight! Soar to the skies! Burn the gondolas and shove Venice in the stinking canals! The exclamation mark would have made a perfect logo for this bellicose group had its members not preferred shrapnel and hurtling cars.

But of all the futurists, the only one who really lived (and died) fast was the painter, sculptor and leading theorist of the movement, Umberto Boccioni. Born in Reggio Calabria in 1882, Boccioni had already trained as a classical artist, sign painter and designer before he met Giacomo Balla in Rome at the age of 19 and followed him fast through divisionist painting. There followed quick flings with impressionism, post-impressionism and cubism, in Paris, before Boccioni found form with the futurists exactly a century ago.

Whether this volatile dandy would have kept faith with his comrades or their efforts to shock the world into a modern, machine-age utopia is anybody's guess. Boccioni died at 33 during the Great War, not in a hail of modern artillery but tumbling from an old-fashioned horse.

For all his letters, manifestos and aesthetic declarations, Boccioni remains an elusive figure and it is to the credit of the Estorick Collection, the best showcase of Italian art in Britain, that it has tried to give him some visible shape. Since most of the best-known works have stayed put in Italy and America, no doubt waiting to fly over for the greater glory of Tate Modern's massive futurism exhibition in June, the attempt has to be something of a failure. But it is a strangely alluring show none the less, not least for raising the ghost of some masterpieces that have mysteriously vanished.

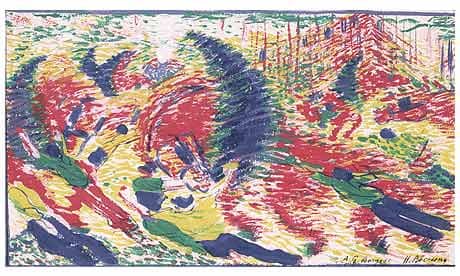

Boccioni aimed for the impossible: he wanted to get some visual fix upon the incessant flux of life - the movement of crowds, the uprush of aeroplanes, the pullulation of noise and bustle and everyday speed, of trains and cars striking through the landscape. And many of his endeavours to this end are homely and not a little poignant.

A little cyclist barrels along on his pencilled bike, nose down, the spokes of the back wheel turning into a cloud of nothing to indicate frantic motion. A portrait of the artist's mother is pure cubism, all fractured angles and multiple viewpoints, except for a halo of radial marks surrounding her head. She is alive, she is moving, she is happening now! You get the idea, but the execution is completely childish. The halo is the futurist touch, what distinguishes it from some drawing by Braque, but the halo resembles nothing so much as a foolish hat.

Speed, vitality, dynamic motion: these futurist obsessions also happen to be among the greatest problems for modern art. How to depict whirling motion in freeze-frame, without a camera? How to get the dancers to dance? How to paint the experience of coursing down the avenues in your Fiat without simply depicting the car?

Boccioni painted a lot of trains in his short life, all of them tending to centre on a number plate surrounded by a vortex of thrashing arcs. Hopeless as intimations of speed sensed from within a machine, they none the less (like so much futurist art) make terrific posters. The best of his painting is more like graphic signage, sometimes captioned with those nonsense sound-nouns the futurists loved. Zang Tumb Tumb sound the cannons! They ought to have been making avant-garde movies.

All except for Boccioni, that is, for what this show really demonstrates is his immense strength as a sculptor. There are photographs of long-lost works - portraits where the head is imagined inside and out, like many-chambered minds; structures that combine man and architecture in startling ways - that reveal an existential imagination which could have become as distinctive as Giacometti's.

But above all there is Boccioni's acknowledged masterpiece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, that magnificent figure striding forwards as if through a driving storm, flesh flapping like clothes in a gale, muscles flanged, torso pressed back upon itself, compressed, impacted, by the sheer encounter of momentum and gravity.

The Estorick curators have commissioned a response to futurism from the overrated Italian artist Luca Buvoli that does nothing but emphasise, in cartoonish terms, the movement's addiction to speed and its fascist tendencies. It feels like irrelevant cultural chit-chat in the face of this great bronze force: a man who seems to generate new configurations of himself as he walks through fire, or trudges through torrents, leaving traces of the body in motion as he goes. It is a tremendous coinage, not bombastic, not theoretical, and paradoxically mired in heavy metal: a collection of marvellous - unique - forms.