‘I’d always avoided art fairs like the plague,” Eric Fischl is telling me in his studio on Long Island, New York, surrounded on all sides by his own larger-than-life paintings of art fairs. “Now I have been I still think they are the plague,” he says. “It’s like every single reason for art to exist does not exist in those places.”

Fischl, perhaps the best narrative painter of his American generation, is 66. He remembers how the plague spread. It was subtle at first. One biennial led to another. There was a sudden rash of Expos. It was one of those things that friends thought would be a fad, he suggests, but after the millennium dotcom crash and the collapse of the art market, the pandemic spread as the art world panicked and desperately tried to resuscitate itself as an asset class.

There are now 50 or more international shows, from Dubai to Shanghai to São Paulo, one for every week of the year, following the money, flogging product. Fischl steered clear of all of them for a long while, but finally went to the shiniest of the lot, Art Basel Miami Beach, a couple of years ago, at the request of New Yorker magazine, for an interview. He became grimly fascinated by the spectacle, took a camera with him there and subsequently to Frieze New York, and to the fair in Southampton up the road from his home in Sag Harbor, Great Gatsby country.

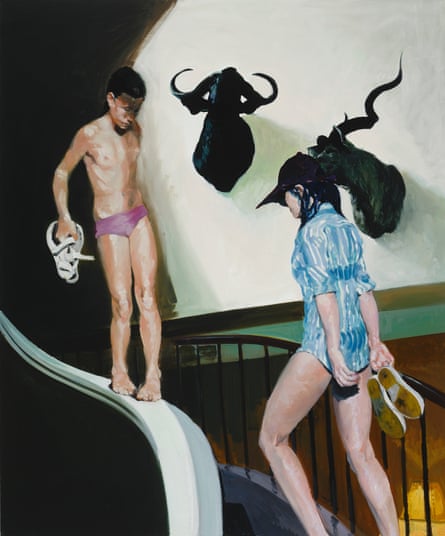

Fischl then made Photoshop collages of his hundreds of photos, creating scenes that might have happened. He gestures to the fabulous painting behind me. “The big sneakers here are from a show of Claes Oldenburg’s. The guy with his back to us was a guard at that show. She on the left was from an art fair at Southampton. That guy was from Miami. I mix and match. Same crowd, different clothes. But always the same experience.”

An exhibition of Fischl’s art-show paintings (priced between £200,000 and £400,000) will open at the Victoria Miro Gallery, in London, this week, to coincide with the Frieze art fair. He hopes that people can go to Frieze and then come to his show and see what they looked like at Frieze.

If you have never been to Frieze, his paintings capture much of its dead-eyed atmosphere, its comic and dispiriting juxtapositions. In Fischl’s Art Fair: Booth #4 The Price, a distracted crowd of buyers cluster around an amorphous Ken Price sculpture, not looking. Behind them, an enormous intimate self-portrait by Joan Semmel goes unremarked. “The big collectors do this kind of speed-dating thing,” Fischl says. “They try to get in and out before anyone buys what they are after and certainly before the hoi polloi gets to look. And then you’ve got people who are just there for the social scene. So you have people texting or not paying any attention at all. It is as if the art is not there, or that they think it has no effect on them. But when you stop the moment you can see this weird world that is taking place. They are being regarded and judged by the work itself in some ways.”

In my experience, I suggest, Frieze provides exactly the enervating experience of a Saturday afternoon at Brent Cross shopping mall, except some of the stuff on sale is priced in the millions. Wealth becomes the spectacle, not art.

“If you start with the premise,” Fischl says, “and I know it is a romantic and naive premise, but I none the less think it is true, that artists are looking for love, and they are expressing love in their commitment to what they have made. An art fair is designed so they never get any in return.” He speaks languidly and laughs broadly. “Love is complicated, obviously. But the reason artists do what they do on some level is to say: ‘Don’t look at me, look at this thing I made and you will know the true me.’”

Fischl himself developed that particular faith as a young painter in the 1970s when he started to try to express himself on canvas, first at CalArts, the Disney-funded art college outside Los Angeles, and later in Nova Scotia, where he took a teaching job and met his wife, the celebrated landscape artist April Gornik, and finally in New York. In a world of abstract expressionism and conceptualism he became part of that endangered species, a figurative painter, a storyteller. Despite this self-imposed handicap, by 1985 Andy Warhol was describing Fischl in his diary as “the hot new top artist”; he was the subject of a long Vanity Fair profile entitled “Bad Boy of Brilliance” which compared him favourably to celebrity artist peers such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat; and his paintings were suddenly selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

To understand how Fischl found himself at the centre of that world, a version of which he now satirises 30 years on, you have to understand where he came from. The paintings that made Fischl’s name were drawn from an adolescence spent up the road from where he now lives, in a town called Port Washington. His father went into New York City every day selling promotional films to corporations in the days before video. His mother, spirited and beautiful, was also an out-of-control alcoholic, the “unspeakable” open secret that Fischl, his brother and two sisters did all they could to contain in their suburban idyll.

Fischl’s early paintings exhibited a disturbing kind of voyeurism, in scenes that might have been written by John Cheever or John Updike. The two defining paintings of that period — Bad Boy, which depicts a young boy standing before a woman, perhaps his mother, sprawled naked on a bed, while he feels for her handbag; and Sleepwalker, in which a teenager masturbates in a paddling pool, bathed in Edward Hopper light – were representative of the uncertain boundaries, the disquieting taboos, that became his constant theme.

Fischl depicted the fallout of early 1960s America at war with inhibition, and deeply troubled by that fact. In his recent memoir, also entitled Bad Boy, he recalls a youth in which his parents talked openly about their sex life and “lounged around their bedroom – where we’d visit after dinner to watch TV – completely naked”. When his mother was drinking, which was often, “her whole face seemed pinched and pulled back. Her artificial expression, a Kabuki-like mask, reminded me of a terrifying drag queen. It was impossible to predict what she might do… ”

Impossible, that was, until the day, not long after he had started art school, when Fischl was called to say his mother was critically ill in hospital after driving her car into a tree, an act of suicide. Fischl got back home just before she died and was overwhelmed by the fact he had “not been strong enough, smart enough” to save her from herself. He subsequently became a painter of what had been “unspeakable” because, he wrote, on “some level I wanted to make her life good”. What did he mean by that?

“It was a thing my therapist spent many years trying to get me past,” he says. “The tragedy of her life was that she was creative and intelligent and stimulating, and if she had channelled that in a different way she could have been amazing. She tried art but she lacked the stubbornness to do it. She couldn’t get past the self-critical thing we all have and she would destroy it or fuck it up or not finish it. When she killed herself, I felt I was making art for her. I thought I could make her pain less by succeeding at this thing where she had failed. Which of course makes it pretty hard to own your own success… ”

It took him many years of messing about with abstraction, and other strategies, to realise he had to confront those experiences head on.

“I actually found it harder to paint a specific chair in a scene than to paint the woman passed out on the floor. Somehow the woman passed out on the floor could have been any woman. The chair became something closer to my particular experience. The first brave step was doing that.”

Did it feel liberating?

“It was empowering ultimately,” he says. “I suppose if I had gotten crushed by the critical reception the way I feared when I started to make these paintings I wouldn’t have continued. When the pictures were embraced, however, I went further and further into it.” The breakthrough was Sleepwalker. “I started to try to paint in a representational manner,” Fischl says, “and it was a stretch because I had never been trained that way. My drawing skills were iffy. Trying to render flesh. I was learning in this painting and people tried to persuade me off it. I was being told: ‘You have to find a way of making it look more contemporary.’ I went through a thousand possible ways to do that but it was always everybody else’s idea. In the end I was left with myself. That is something that all artists ultimately have to find: the thing that they can do that doesn’t look like art.”

It seems strange to be talking to a contemporary artist about emotional authenticity, about representation, and about the influence of Degas and Manet rather than Warhol and Joseph Beuys. “There are two kinds of painter, if you like,” Fischl says at one point. “One is somebody like Hopper who creates an image that burns on your retina and you never forget it. You can see it, walk away and still see it. [With] the other kind you are caught up in the authenticity of the energy. The believable moment. Jackson Pollock, you are right there with him. I am essentially the Hopper artist trying to create a frozen moment. The truth about how it actually was.”

Despite that commitment, or because of it, Fischl found himself co-opted into the wild and whirling art world of 1980s New York – his first experience of the milieu he has lately been documenting. Warhol visited his studio, and offered his blessing. “He sought out youth, he was always curious about what was going on,” Fischl recalls. “Most of the artists we admired wanted to be outside society looking in. Warhol wanted to be right at the centre of high society and still be radical. It was as if he wanted to infect it from the inside out.”

Looking back on what quickly became a frenzy of parties and gallery openings and cocaine and booze and money – which had little to do with his original change-the-world ambitions for his art – Fischl admits it was nevertheless “all incredibly exciting. It was like a spinning world, it had real centrifugal force. Traditional art magazines couldn’t keep up so the dailies took their place. Artist’s photographs were appearing in the arts and entertainment pages next to those of rock stars and film stars. It was like a wave had picked us up.”

Fischl was beached not long after just as surely. After one bender too many, after the opening of a solo New York show, and a near car crash, he knew he had to remove himself from the centrifugal world he found himself in. He has a sense that he inherited his mother’s addictive gene, and that he had welcomed the self-destructive aspect of it in some way “in order to survive it, to prove it could be done”. With premonitions of an art world about to finally sell its soul he packed up his studio in New York, moved with April Gornik the two hours out here – following an artists’ path trodden by Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and others — and swapped his previous narcotic highs for more life-affirming ones.

Fischl counts Steve Martin and John McEnroe among his closest friends. After McEnroe opened a gallery in New York on his retirement, Fischl tutored him in art history in return for tennis lessons. He plays most days, sometimes with McEnroe himself, and likes to make connections between his game and his work (“both are performed in a rectangle, and are about gesture and reach and executing an intention, resistance”). He and Gornik bought some land and built their beautiful, brutal 10,000 sq ft minimalist home on the edge of a salt marsh, complete with matching studios. They moved in on millennium eve and Fischl entered what he calls, with a laugh, “his long mid-career period”.

From this vantage, Fischl believes himself to be an outsider to the kind of world he describes in his art-show paintings. His work has continued to sell – his record for a single picture was the $1.9m paid for his painting Daddy’s Girl in 2006 – and he has moved on from adolescent angst to document and interpret the worlds he now inhabits. He has cast, for example, his unnerving eye over the plutocrats at play in St Tropez as well as the Hamptons.

He is surprised at the way his career has gone. “I had this idea that I was making work that would be shown in museums but that nobody would really want to live with,” he says. “I mean who the fuck wants to wake up and have breakfast with somebody jerking off in a pool? I overestimated museums, though. They were the ones that wanted to put up warning signs in front of the work, whereas the private sector bought it. I would have liked it to be more a public art.”

That particular frustration has crystallised recently around two projects, which were the real cause of his decision to turn his painter’s eye to the art world itself. Both projects were made in response to what he saw as the fracture in US culture after 9/11, and the inability of the art world to address it.

In 2002 Fischl, who has been working more and more in sculpture since he moved to Long Island, made a public statue, Tumbling Woman, which was to be a permanent fixture at the Rockefeller centre in New York. The life-size bronze sculpture – he has a smaller version outside his studio – shows a human figure apparently in free fall, just above the ground, as if in suspended animation.

“9/11 was so profoundly shocking – that we could be that vulnerable, that powerless,” Fischl says. “And it was combined with something really freaky: 3,000 people died and there were no bodies. How do you process the mourning? It was like a surreal disappearance. The only way we knew how horrific it had been was in the images of the people who jumped out the windows, that they would choose to die that way. Right away though, the media self-censored and got rid of those images. I thought that was wrong.”

When Fischl’s simple human sculpture was unveiled, there was an outcry. A New York Post columnist suggested it was a cruel and self-serving image and accused him of “riding on the backs of those who had suffered grief and loss in an effort to revive a moribund career”. After that he became public enemy number one.

Who fought his corner?

“Nobody. My dealer tried to protect me a bit from the hysteria. Friends in the press said I should let it drop. The guy who owned Rockefeller Centre, a big art patron in the city, removed the sculpture. He told me he was getting bomb threats and he couldn’t take the risk.” Fischl laughs bleakly. “I told him: ‘No one is going to bomb you over a statue.’ But that is the world we live in.”

Nearly a decade later, in another effort to use art to help communities come together around an idea of America, he laid plans for a touring art show, a basis for a national conversation called “Now and Here”. The idea was to have the nation’s leading artists and poets and musicians make a travelling event that would offer an alternative to the tribal and polarised nature of political debate. “We have been screaming and yelling at each other for years. Still are. I believed art could provide images as a starting point for dialogue. I thought the hard part would be getting the artists with these huge international reputations to get together and think about the same thing at the same moment for once,” Fischl says. “But of course it turned out to be the opposite. The artists were easily persuaded but the money – we tried for funding from corporations and billionaires – never was.”

Fischl was told again that his idea was just a careerist strategy, as if that was the only reason any artist might do anything. “Instead of any grown-up conversation, what we have instead, what America apparently wants, is artists who are doing very expensive toys,” he says. “Jeff Koons is a good example. What kind of culture expresses itself only in childlike behaviour? Shit jokes and childish humour – and is greeted with huge popularity.”

Fischl’s art-show paintings, for all their cool comic appeal, were made to portray the emptiness of that compact. “That world has just become a celebration of money-making,” Fischl says. “I went to a fair a few weeks ago and in the middle of this thing was a De Kooning painting. I thought ‘Wow!’ It turned out it was in a booth for a real estate company. They had this De Kooning for sale as well as the $40m homes. You could buy the house and get the painting for an extra $5m or whatever. The barriers have collapsed between the commercial and the art world. It is not irony – it is just cynicism. The work is not intended to have you look and think twice, which is what irony does. It’s cynical in that they couldn’t give a shit whether you get it or you don’t get it.”

Some of the people in his paintings are clearly recognisable, though he is not interested in putting names to faces. Has he had any response?

“I did have one experience where a girl in one of the paintings saw it at the New York Frieze show and called me the next day to say she believed she was in my painting. She was really thrilled of course. The thing is we don’t see ourselves as characters – so I think people will look and not always see themselves. And anyway, 10 years from now no one will know any people in it.”

Does he believe that all those who recognise themselves as faces in the art crowd see it as a form of flattery?

“I don’t really care, to be honest,” he says. “For me it is more like an admission that this is my world and this is what it looks like.”

Eric Fischl: Art Fair Paintings is at Victoria Miro, London, from Tuesday until 19 December at the Victoria Miro gallery, 16 Wharf Road, London N1

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion