Fronted by a dramatic gated arch, its roads fringed with neatly trimmed hedges, palm trees and lush grass, Bahria Town bears little resemblance to the urban chaos of nearby Karachi.

The economic heart of Pakistan is an overcrowded and often violent megacity with an official population of 15 million (closer to 20 million if the urban sprawl beyond the city perimeter is included). Infrastructure has not kept pace with its rapid expansion, and basic amenities such as water have become a commodity for criminal gangs. The city is also an organisational centre for the Pakistani Taliban, who attacked the airport in 2014.

Bahria Town expands over Karachi’s eastern periphery, and offers residents a way to buy their way out of proximity to criminal gangs and terrorists, hectic traffic and power cuts. The wildly ambitious housing development is the brainchild of the property mogul Malik Riaz, one of the 10 wealthiest people in Pakistan and a close associate of the country’s former president Asif Ali Zardari.

The new city promises to “turn the vision of modern Pakistan into a reality”, with private and secure supplies of water, gas and electricity, as well as privately maintained roads. The developer, also called Bahria Town, says it is Asia’s largest private real estate company, employing 25,000 people. It has already built smaller planned communities outside Lahore and Islamabad, but the 45,000-acre Karachi project is on a different scale.

Q&AWhat is the Cities from Scratch series?

Show

Scores of new cities are rising across the world from previously untouched desert and jungle, or on land “reclaimed” from the sea. While the history of cities built from scratch is long, the scale of the current epidemic is beyond anything seen before.

Another 2.5 billion people are predicted to move to cities over the next 30 years and the trend shows no signs of stopping. New research has identified more than 100 examples, nearly all in Asia and Africa.

This week Guardian Cities meets the 90-year-olds who built the Bulgarian city of Dimitrovgrad after the second world war (many still live there) and visits the bizarre Bahria Town development promising Karachi residents protection from terror attacks and violent crime. We look at Hong Kong’s plan to build artificial islands for 1.1 million people and examine Egypt’s dream to conquer the Sahara. We remember past visions of future cities and ask, is there ever a good reason to start a city from scratch?

Once complete it will accommodate 1 million people, and is already home to a zoo, an 18-hole golf course and a theme park featuring fairground rides. The site is dotted with scaled-down imitations of world attractions such as the Parthenon and the Eiffel Tower. Smooth tarmac streets lined with palm trees and uniform villas eventually peter out into rocky construction sites, and unfinished properties dot the sides of the road. Construction has begun on a mosque complex that will be the third largest in the world.

Bahria Town’s website offers Karachiites who can afford it the chance to live “amidst soft grass and pure class”, advertising its luxury villas as “Pakistan’s first lifestyle community developed around a huge green area inspired by Central Park, New York, with a replica of Taj Mahal”. The residences on offer range from apartments to standalone villas to luxury farmhouses, at a range of prices targeted not just at Pakistan’s elite but at the middle classes too.

Although the vast development is only part-built, more than half of the plots are reportedly sold. Some sections are already inhabited, and facilities including a large modern hospital, the theme park and Pizza Hut and Burger King restaurants are already open.

For many Pakistanis, the modern convenience offered by Bahria Town is an attractive proposition. “Since before my son was born, I have been saving to one day buy him a residence for his own family – and now it makes sense to buy here because it looks like the future,” says Asif Munir, a small-business owner from Karachi who is considering purchasing a plot. “The cost of the apartment includes not just reliable water and light but safety because it is far away from criminal gangs.”

But the development has been mired in controversy since its inception in 2014, most notably over allegations of illegal land appropriation. In May last year the supreme court ruled that much of the land had been illegally procured. In December, it ordered a halt on all construction. As the case works its way through court alongside a simultaneous case in the National Accountability Bureau anti-corruption court, villagers who have lived in this area for centuries are feeling the impact.

‘We broke purdah to defend our homes’

The village of Usman Allah Raki Goth has been here since the 1800s. From its small cluster of houses, school and mosque, you can see the silhouette of Bahria Town’s theme park and neat rows of apartments. Despite the village’s proximity to Karachi, the country’s economic capital, life here is basic. Many residents do not have access to running water, gas or electricity, and rely on agriculture for their livelihood and sustenance.

In 2014, the village elders were approached by the developers. They struck a deal, agreeing to sell off a portion of their land used for cattle grazing, in exchange for a sum of money and a promise that the village would be connected to Bahria Town’s water, gas and electricity.

According to Ali Gabol, nephew of a village elder, after two years of construction only a quarter of the money had been paid and the promised connections had not appeared. “The deal was off,” he says. Then bulldozers arrived at the village and started to tear down the mosque, graveyard and homes. In a scene of resistance that has been echoed in villages across the district, the women came out of their homes and pelted the bulldozers with stones until they left. “We knew they would arrest the men if they fought back, so we broke purdah [the practice of women staying inside] to defend our homes,” says Saba, Gabol’s wife.

Today, the graveyard in Usman Allah Raki Goth remains partially destroyed. Half of it is still visible in the dust, but on top of the other half an extravagant archway and a half-built water fountain featuring sculptures of metal birds have appeared. They will form the opening to a farmhouse, one of the more expensive types of property on offer in Bahria Town. Before the court-ordered halt in construction, bulldozers returned frequently, with construction workers seeking to demolish other parts of the village to construct a road. Bahria Town did not respond to requests for comment.

Bahria Town already expands over more than 12,000 acres. According to Hafeez Baloch, a land activist who lives in the nearby settlement of Kathore, 48 villages have been affected. The majority of losses have been of agricultural or pasture land, rather than houses, but if a family are unable to take their cattle or goats to pasture, their source of food and income is removed. “An attack on your land is an attack on your sustenance,” says Baloch.

In March, construction resumed. In the aftermath of the court verdicts, there have been reports that Bahria Town has struggled to pay salaries, and people already resident there have faced the very power cuts and water shortages they had sought to escape. For many villagers who live in the vicinity, though, the damage has already been done. “Buildings and roads can’t come down,” says Baloch, “but they mustn’t expand. This is our land. We just want to stay here.”

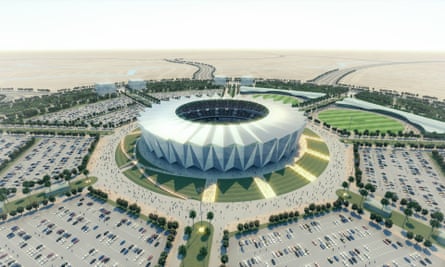

Bakhtawar Kachehlo lives in Shafi Mohammed Goth, another village on the periphery of Bahria Town. The construction site of Sports City, which will ultimately host Pakistan’s largest cricket stadium, a running track, and a five-star hotel, looms nearby. Last summer, Bahria Town bulldozers destroyed several poultry farms owned by villagers to make way for a road. Residents do not have the money to rebuild the farms and have lost a vital income stream. They are concerned about what will happen now the supreme court limitations have been lifted.

“When they first came and started to build their own setup, we were happy that a city is being built around us, we thought we’d get health and education facilities,” says Kachehlo. “But now that they’ve attacked us, we know we will not reap any benefits from all this construction. They’re building mansions for themselves and even trying to ruin the little shacks that we have.”

Reporting for this article was supported by a media fellowship through the Center for the Study of Social Difference at Columbia University

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter