The one new piece in the latest exhibition from the photographer and film-maker Larry Clark is a typically ripe collage entitled I Want a Baby Before U Die. An extreme close-up of a woman's pubic hair, beneath which is visible the tattooed name "Larry", competes for our attention with images of guileless teenagers having sex. Elsewhere, newspaper reports of violent adolescent deaths jostle for space with pictures of buttocks caked in a substance one hopes is Nutella.

Oddly, there's also a cinema ticket for Harry Brown, 2009's British vigilante thriller. Its title character, like Clark, is a pensioner preoccupied with teenage delinquents. But, whereas Brown guns down thugs, Clark would be more likely to take them skateboarding and then snap them with their junk hanging out.

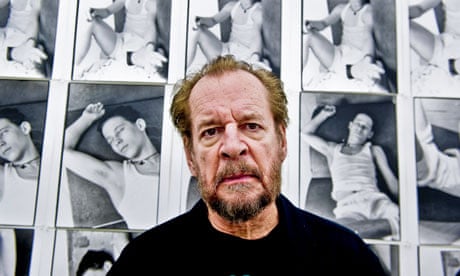

This exhibition, entitled What Do You Do for Fun?, is culled from a retrospective that opened in Paris last year to the sort of controversy without which nothing bearing Clark's name would feel authentic. The city's mayor banned under-18s from attending. "They tried to censor me – and in France!" splutters the 68-year-old, who is tall and stringy, with warm brown eyes, salt-and-pepper bristles, and hair swept back from his long, boney face.

The outcry helped him through a minor crisis of confidence, a feeling that his work was becoming obsolete now that any teen at any party could capture by phone the kind of scalding images that are his bread and butter. "No one knows anything about photography," he grumbles. "It should be about light and shadow and feeling. Look at porn: it's so ugly these days, people filming themselves doing it with their girlfriends." He sounds like a purist complaining about the inept hanging of an Old Master. "But then I do Paris and it's crazy time. So it gives me pleasure to know my work is still dangerous after all."

The intent, he says, was never to shock, but to be honest about what it means to be young. "All my work has been about small groups of people you wouldn't know about otherwise," he says, proudly. His influence on popular culture began 40 years ago with the publication of Tulsa, a photographic record of junkies in the Oklahoma town of his youth. The book opens with Clark's own declaration of addiction ("Once the needle goes in, it never comes out") and captures with chilling starkness the aimless smackhead existence: shooting up, goofing around with guns, having sex and shooting up again.

"Some people liked Tulsa because it was anti-drugs. Art scholars liked it. And girls in black motorcycle jackets wanted to fuck me. It was a complete sweep." But it wasn't until his 1995 debut film, Kids, about the drug-fuelled, sexed-up, cruelly violent lives of New York City teenagers, that Clark became a cause celebre beyond the art world. People tend now to think of him either as a sympathetic champion of marginalised youth, or as an old pervert whose brand of research – spending months gaining the trust of his street-punk subjects – might easily be confused with grooming.

How does he answer the criticism that it's unseemly for a man in his 50s, as he was when he shot Kids, to be filming teenagers in exposed states? "Someone in their teens should have made that film," he replies. "But someone that age couldn't have made it. They wouldn't have the perspective or clarity. They'd clean it up in certain ways."

'Most everyone's dead now'

What about the process of soliciting teenagers to participate in his work? The act of approaching young people with an invitation to take their picture would be a comical cliche if not for its overtones of paedophilia. But Clark, who has two adult children of his own, insists his approach is painstakingly responsible. "It usually takes a while for them to accept me. I'll meet their parents, talk things over."

Before making Wassup Rockers, his film about 14-year-old Latinos from LA, he spent many weekends hanging out with his subjects. "I took them skating. I'd listen to them, write down their stories." If Clark's work leaves some adults queasy, it's largely embraced by the young: he says the best compliment he ever received was from a boy who said of Kids: "That wasn't like a movie at all. That was like life."

This dogged pursuit of candour underpins some of the collages in the new show. Magazine pin-ups of teen idols are placed alongside brazen pornographic snapshots: it's the former – the industry-sanctioned posters of young boys showing off porcelain midriffs, or coquettishly exposing a nipple – that come off worse. Clark challenges what he now calls "the Hollywood lie about teenagers" by juxtaposing screen grabs of the young Matt Dillon from Little Darlings with newspaper articles about adolescent deaths from auto-erotic asphyxiation.

This feeds into the exhibition's most arresting piece: an entire wall of 200 black-and-white prints, each showing the same rodent-like teenage model, genitals visible through his shorts as he strikes suicidal poses with a noose or a gun. This 1992 project heralded Clark's move away from the reportage of Tulsa and 1983's Teenage Lust, and towards fully staged photographs with a heightened narrative – what he now admits was a preamble to the second stage of his career, film.

He had wanted to be a director all along. Indeed, the exhibition includes previously unseen 16mm footage of the Tulsa crowd. Clark's voice cracks slightly when we pause before the flickering images. "Most everyone's dead now," he sighs. "Watching it again, my friends come to life for me."

In 1990, he saw Drugstore Cowboy, Gus Van Sant's tale of itinerant addicts. "I said to myself, 'This motherfucker's on my turf! I gotta make a film.' I'd been a drug addict alcoholic for so long, but Gus doing that picture made me get clean and rehabilitate my image so I could get the money to make my own film." Clark started hanging out in New York's Washington Square Park, befriending the teenagers and using their stories in the outline that 19-year-old Harmony Korine turned into a script. "The kids would wear these free condoms on a string round their necks," Clark recalls, "and they all gave me the safe-sex talk. But as they got to trust me, they started telling me the truth: 'I wouldn't use a fuckin' condom on a bet. Fuck that shit!'"

The "virgin surgeon", a predatory character in Kids who tries to avoid Aids by preying solely on virgins, was based on a boy Clark met. "Over a few months, I saw him seduce three different virgins. I said to him, 'What if one of 'em gets knocked up?' He said, 'It's not in the cards.'" As Clark talks, his belief in the moral purpose behind his work becomes apparent: it's all about casting off the comforting facade about teenagers, just as his earlier photographs tried to alert America to the drugs crisis brewing under its white-powdered nose. Clark's images are rarely pretty, even when his actors and models are. But he has no current equals in capturing the artless, distracted poetry of unselfconscious youth.

How Kids gave birth to Skins

"People were outraged by Kids. They said it was the fantasy of a dirty old man. But all you had to do was read the newspapers and you'd see it. I just got in there early. Same with Tulsa. I'd been taking drugs since the 1950s, so I saw drugs were bad, and when the hippy thing came around I already knew it was bullshit. Drugs were a shameful secret when I was a kid. Whatever happened to shame?"

If he didn't glamorise the junkie lifestyle, his aesthetic was appropriated by those who did. "They took my influence and used it to sell shit. Art is always co-opted by commerce." Even as he saw echoes of his photographs in the rise of "heroin chic" fashion journalism, he never capitalised on it himself. "I'm an artist," he shrugs. "I can't do commercial work. If I could, I'd be a zillionaire. I've been offered so much but it means nothing to me."

He's well aware of the impact his films have had, too. Skins, the British TV drama about hedonistic Bristol teens, is essentially Kids UK. Young film-makers still talk about Kids in reverential tones. "I love how frank and non-judgmental Clark is," Olly Blackburn, the director of Donkey Punch, once told me.

Clark's subsequent films have enjoyed mixed fortunes: 2002's sexually explicit Ken Park was consigned to the shelf in Britain, after Clark punched the distributor during an argument about 9/11.

He has several scripts ready, but can't raise the money. "I could make a Hollywood film if I gave up control." Liar, his script about the youth scene spawned by Kids, was rejected by a cable channel. It features a film director called Larry Clark who is killed by one of his young actors. "He gets pushed off a roof," Clark grins. "And the last thing he does before he hits the ground is to take a photograph."

Larry Clark: What Do You Do For Fun? is at the Simon Lee Gallery, London W1, until 2 April. Details: 020-7491 0100