To reach Walter Bonatti by car is a nightmare. You head north-east out of Milan towards the lakes until you reach the town of Dubino. There are no signposts and you have to negotiate a series of ever narrower lanes that zig-zag their way up the steep hillside on the sunny side of town until you realise you've come to a dead end. You've made it to Casa Bonatti. To reach Bonatti by mail, all you have to do is write to Walter Bonatti, Dubino. Walter Bonatti, Italy, would probably do.

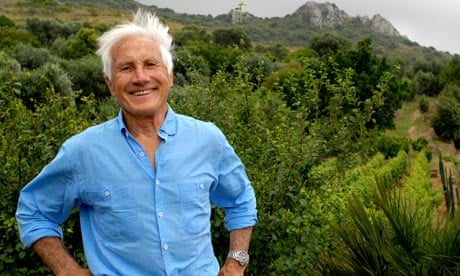

Bonatti, the greatest alpine mountain climber of his generation – or any other, many would say – and one of the finest writers on climbing (his classic The Mountains of My Life has just been republished in the UK to mark his 80th birthday ) is a national hero in Italy. All over the country, young people who weren't even born when he gave up climbing in 1965 at the age of 35, stop him in the street to shake his hand. It's a recognition not just of the climbs he made – in particular, the south-west pillar of the Aiguilles de Dru, Le Grand Capucin and the north face of the Matterhorn – but of the spirit in which they were made; the mismatch of human frailty against the immensity of nature that Bonatti kept on overcoming.

But it wasn't always like this. After assisting in the first successful ascent of the Himalayan peak of K2 in 1954, Bonatti's name was anything but heroic in many parts of Italy after he was accused by the lead climbers in his expedition, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, of trying to compromise their summit bid by using the oxygen that was intended for them. It was a very Italian feud, with Bonatti's reputation sacrificed for the greater good of restoring national morale in the aftermath of the second world war – and it would be more than 30 years before the truth came out.

After K2, Bonatti chose his friends and climbing partners ever more carefully and acquired the tag of the chippiest, most difficult character on the ice block. But time heals many wounds and these days he's chilled, charming and charismatic.

Climbing is more than just an exercise in strength and skill for Bonatti; it's a philosophy, a way of life, one that he believes has now come to an end. "The old traditions of alpinism are dead," he says. "Modern equipment is so technically advanced you can climb anything if you put your mind to it. The impossible has been removed from the equation."

It's not the lament of a grumpy old man who can't bear progress. Climbing has undergone such a profound category change that it bears little resemblance to its past. "I used to head off with just a few wooden pitons, some old hemp ropes and a bivouac," Bonatti says. "It was often just me and the wilderness for days on end; complete solitude with no one knowing quite where I was or what I was doing until I returned. With mobile phones and GPS, the dimension of being utterly alone has utterly disappeared; even when you're halfway up a mountain you're still connected to the outside world. It's not good or bad; it's just different."

As a child Bonatti dreamed of the wilderness. "I had read Jack London, Melville and Hemingway," he says, "and I would sit by the banks of the Po near my parents' home and plan adventures. When the river was in flood whole branches of trees that had been ripped off upstream would race by and I would fantasise about one day following them out to sea and to wherever they washed up."

The war switched the course of those dreams upriver. Bonatti spent much of the period out of harm's way on his uncle's farm, yet even from some miles away it was impossible to escape the din of the attritional Battle of the Po in the spring of 1945. "Ten days after the fighting, I walked to the battlefield," he says. "It was carnage. There were burned-out vehicles and bits of bodies strewn everywhere, in the river and on land. I knew then that the river offered no escape, so I looked to its source and saw the mountains. In that moment, I decided that climbing was to be my life."

Within a few years Bonatti went from complete unknown to one of the most celebrated climbers in Italy. At 18 he made only the fourth ascent of the north face of the Grandes Jurasses and two years later the first solo ascent of the Grand Capucin, a red granite pinnacle in the Mont Blanc massif. "It was such a strange time," he says. "My home town of Monza laid on a civic reception for me and my mother was so proud, as she had lost everything in the war. Yet just as I was being honoured, she collapsed with a heart attack and died. For many years I couldn't stop myself from thinking it was my success that killed her."

Military service offered some relief. Bonatti was assigned to the Alpine regiment and for four days each week he trained men to climb; for the other three he was allowed to head off into the mountains on his own. By 1954 he had become an unavoidable selection for the Italian assault on K2, the one that would cause him all that trouble.

"It was the era when European countries picked off the 8,000m peaks in the same way they had colonies 100 years previously," he says. "There was a lot riding on the expedition's success. At 24 I was the baby of the team, but my achievements in the Alps had made it impossible for me to be left behind."

The expedition was riven with tensions from the off as Bonatti had proved himself to be easily the most capable of surviving high altitudes, and yet the more experienced Lacedelli and Compagnoni were chosen as the climbers to reach the summit. Bonatti's job was to ferry oxygen to them. It was on the climb with Mahdi, their Pakistani mountain guide, to the final camp before the summit that the difficulty started.

"Lacedelli had placed their camp out of sight more than 250 metres away from where we had agreed," says Bonatti, "so Mahdi and I were forced to bivouac out in the open at 8,100 metres. Throughout the night we had to keep digging out our snow hole and by morning Mahdi had severe frostbite."

Why had the summit pair moved camp? "To kill us," Bonatti says bluntly. "It may sound farfetched, but they were terrified we were in such good shape that we would be able to accompany them to the summit without using oxygen." Which would have detracted, of course, from their own oxygen-assisted summit.

In fact, Bonatti did deliver the oxygen, but Compagnoni and Lacedelli accused him of forcing them to make the summit unaided. "And that's the version of events that survived for many years," says Bonatti, "until photographs were found proving that both climbers had used oxygen at the summit. But old habits die hard . . . the Italian Alpine Club still insist the K2 ascent was done without oxygen."

Understandably, Bonatti came back from the Himalayas feeling somewhat bruised. He tried to organise a solo ascent of K2 without oxygen the following year to put the record straight but couldn't get the backing, so he retreated to Courmayeur, where he became a mountain guide in between planning spectacular climbs.

"I chose the ones that interested me," he says, "and when there was nothing left for me to do save repeat myself, I stopped. Every climb I did was about challenging myself, about not knowing if I had what it took to survive. I seldom felt a feeling of great triumph when I made it to the top; that feeling came when I was on the mountain itself and I knew there was nothing that could stop me. I survived because I understood the mountains. It came to the point where I could sense danger. On one climb I looked up at an overhang and instinctively moved away from underneath it. Within seconds it had collapsed, cascading rocks on the spot where I had been."

Here, Bonatti's wife, the actress Rossana Podesta, interrupts. "This mountain sense has never left him," she says. "A few years ago we were out walking in the mountains with a group of people. It was sunny and the terrain was quite flat, and there was no sense of danger. Suddenly Walter shouts at me and a young man to stop where we are. Moments later a crevasse opened up that would have killed us had we carried on walking."

Bonatti's sudden retirement was not greeted with universal sadness. While the French government awarded him the Legion d'Honneur, some Mont Blanc guides chose to puncture the tyres of his Volkswagen and burn down his house. "They never really accepted me, as an outsider," he says. "Luckily for me, they also didn't realise I had already sold the house . . ."

His second career saw him travel the world as photojournalist, and his books are read in every Italian school. Yet it is as a climber that his legend was made. So are their regrets? "Not really," he says. "I would have liked to have climbed the Eiger. I once got about a third of the way up in a couple of hours when the rockfalls began, so I came back down. You see, the real essence of mountain climbing – of really knowing and loving the mountains – is not getting to the top. It's having the humility and self-awareness when necessary to be able to stop 100 metres from the summit and make it down alive."