This profile first appeared in the May 1973 issue of Town & Country.

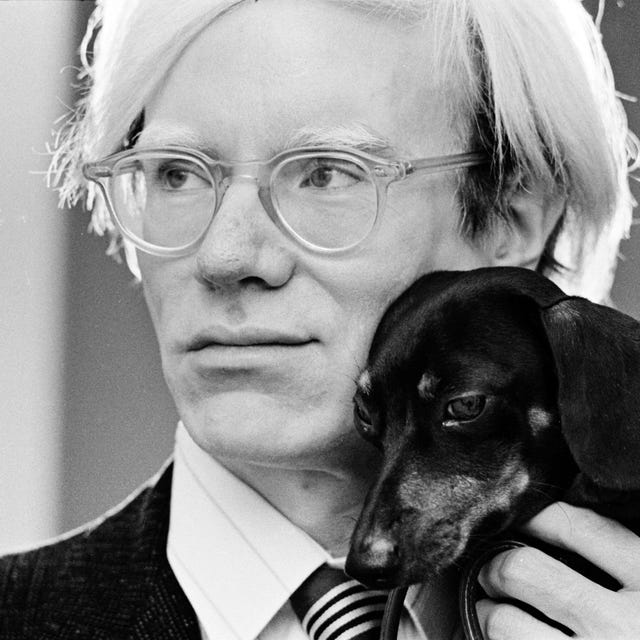

It is hard to believe that he was once chubby, even roly-poly, cute enough to get away with signing one of his pictures, “Andy-Pie.” Today, at 42 going on 43, Andy Warhol is skin and bones, all knobby knees through the soiled and rumpled jeans, and long bony arms. The cords of his neck stand out around the prominent Adam’s apple. The ugly-handsome face is thin and pale and pockmarked, the expression pensive and a little frightened, topped off by the celebrated Warhol trademark, the shaggy silver-white toupee. But most arresting are the hands—non only thin, long-fingered, and delicate but also gnarled and calloused and strong looking, the hands of a fragile steelworker.

What has happened? Has he been sick? To be sure, when he was shot and very nearly killed by one of his would-be superstars named Valerie Solanas—who claimed he was trying to consume her life—the ensuing fight for his own life was a physically draining experience. (Valerie was recommended to him by the Women’s Liberation Front, and he has been distrustful of the Movement ever since.) But once one knows Andy Warhol, one suspects that his present appearance is not accidental, but calculated. Whereas he used to have no corners, he has now reshaped himself along the lines of the Hard Edge school of painting, which he himself did so much to help create.

People meeting Andy Warhol for the first time often emerge from the experience feeling as though their brains had been systematically stuffed with a mixture of cotton wool and Brillo. Not long ago a reporter arrived to interview Warhol at the appointed hour of three o’clock, only to be advised that Warhol had just gone out and was due back in about an hour. Laying this to artistic absent-mindedness, the reporter waited. At four o’clock a second journalist arrived, also to interview Warhol by appointment. At that point the interviewee materialized, as if by magic, and said, “Look, why don’t you two just interview each other?” The first journalist wanted to talk about Andy Warhol. The second wanted to talk about his late friend and superstar, Edie Sedgwick. And so, while the two talked at and around Andy Warhol and to each other, Warhol sat with his tiny dachshund, Archie Bunker, in his lap and snapped the reporters’ pictures with his new Polaroid camera, answering direct questions with shrugs or vague monosyllables. Warhol also had two tape recorders going. Why two? “So one can record the other,” he explained. What had happened, of course, was that the journalists had been trapped in the web of a Warhol artistic scheme rather like one of his split-screen movies, in which jarring and unrelated events take place simultaneously before the audience. They, not he, had become the performers.

“Andy is a kind of oracle,” says one of the various young assistants, onhangers, and admirers who compose the worshipful Warhol retinue, all of whom regard the master as a genius and a prophet. “He has the most fantastic mind and the most fantastic memory for everything. He can run into someone he hasn’t seen for years, and immediately he’ll start asking them about problems they were having years before—that sort of thing. He retains everything—it’s just fantastic!” And yet, when asked direct questions, the oracle often sounds more like Dopey the Dwarf than the Oracle at Delphi: “Gosh, I don’t know … Maybe … Gee, I don’t know … I don’t remember who that was … I’ve forgotten her name, but she had yellow hair, or maybe black,” speaking in a soft, hesitant voice with an occasional shy stammer. In the middle of the conversation, the telephone rings and it is the Daily Express calling from London, wanting to know details of his upcoming lecture at Oxford. “Gee, am I giving a lecture at Oxford?” he says to one of his acolytes, who is relaying the message. “Look, you talk to them. Tell them you’re me.” Then, trying to be at least vaguely explicit, Warhol says: “Don’t ask me about anything, because I don’t know anything about anything. If you want to know about me, just look at my paintings and films and me—and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

What is behind it, however, is both method and mischief, and a perpetual Mad magazine sense of put-on. “Everything Andy says is a put-on,” says his friend Ethel Scull. “I’m not talking about what he does, but what he says.” Another friends says, “Andy never says anything; he just says a lot,” which is another way of putting it.

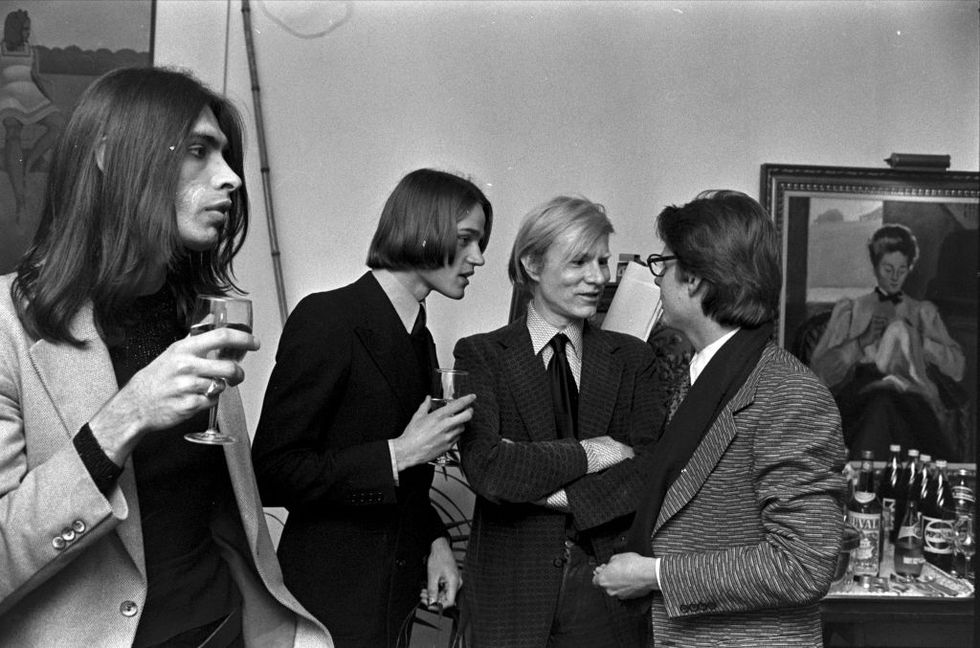

Another way to understand what Andy Warhol is getting at is to remember that whenever he says anything he means more or less the opposite. I say “more or less,” because there are no such things as true opposites in the Warhol world of pop. A Campbell’s soup can painted blue, green, orange, and purple is not the opposite of the conventional can in red and white and black. A silver wig is not the opposite of Andy’s natural mouse-brown hair. It is all, on the other hand, a gesture in roughly the opposite direction, all carefully calculated by an extremely shrewd and ambitious mind to attract attention (the silver hair makes him a stand-out in any group), curiosity (what does he mean by that?), mystery, and, in the end, fascination. In the years since 1962, when he became an overnight star with his show of soup cans and soap pads at New York’s Stable Gallery, Andy Warhol has gone from painting to film making to authoring and lecturing to the point where, today, he is the darling of New York and international society, coveted by hostesses ranging from Manhattan’s grand dame Mrs. William Woodward to the Paris Rothschilds, who tossed a fancy-dress ball for him. He has become a huge celebrity in Europe, particularly in Germany, where one of his paintings was recently bought for $60,000. Both famous and rich, his most extraordinary accomplishment has been his ability to turn himself into his own most successful example of pop art. He is, as one critic has pointed out, the artist as artifact.

Of course, he insists that he doesn’t care about money, doesn’t like publicity—despite all those photographers from Women’s Wear Daily snapping his picture when he emerges from lunch at La Grenouille with Diana Vreeland or appears with Marion Javits at Norman Mailer’s much-publicized birthday party. And yet, pasted in heavy scrapbooks stacked high in his studio are all the clippings from Time and Vogue and Eugenia Sheppard’s column, all pasted and labeled and dated. He has managed his own promotion campaign, so skillfully that when, in 1970, two books about him were published at about the same time—both titled, imaginatively, Andy Warhol—Hilton Kramer, the distinguished art critic of The New York Times, reviewed both books lengthily to say that neither book was worth his attention (but they got his attention). Andy Warhol says that he “can’t remember” the name of the girl who shot him in 1968. And yet nearly one whole scrapbook is filled with clippings about the episode—the front-page stories and pictures, the follow-up stories collected from newspapers all over the country—leading one to speculate wildly: Could he possibly (but he couldn’t!) have staged the whole thing himself?

Even his name is an artifice. Originally it was Warhola, a Czech name, but he decided that Warhol had a stronger, harder (War-Hall), and more memorable edge. For a while he was Andrew Warhol, but Andy sounded better. He was the first person to show up at the Metropolitan Opera House wearing jeans and a leather jacket, when everyone else was dressed up. It caused a sensation. He papered the wall of his original “Factory,” as he still calls his studio, with silver foil. It drew comment. At a Paris exhibition of his famous “Flowers” paintings, he announced that he was retiring from painting. That made headlines, but he didn’t retire. He placed an advertisement in The Village Voice, saying: “I’ll endorse with my name any of the following: clothing, cigarettes, tapes, sound equipment, rock ’n’ roll records, anything, film and film equipment, food, helium, whips, money—Love and kisses, Andy Warhol. EL 5-9941.”

In 1967, he sent out a friend, Allen Midgette, to impersonate him at a series of lectures at the Universities of Oregon, Utah, and Montana and at Linfield College, Oregon. The officials at the University of Utah got suspicious and refused to pay the $1,000 fee. Warhol admitted the hoax, and the whole thing was widely written about. At a lecture at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey, Warhol did show up—with five uninvited friends—marched onstage and declared, “ I really wasn’t prepared to speak this evening, you know,” and with that, sat down, and said no more. The friends answered questions for him. “Oh well,” wrote a reporter for the local paper, “at least he was wearing a purple shirt.”

In 1968 he did a television commercial for Schrafft’s: “The Chocolate Sunday Photographed for Schrafft’s by Andy Warhol.” In 1968 an associate named Brigid Polk was quoted as saying that she did all of Warhol’s painting for him. “Andy? I’ve been doing it all for the last year and a half, two years. Andy doesn’t do art anymore. He’s bored wit it. I did all his new soup cans.” Warhol neither confirmed nor denied Miss Polk’s statement, which caused more comment. In 1971 he accounted a new system of painting. “One of my friends usually accompanies me around New York where we take ink-pad impressions of the male or female breast. You can make a book about it. The impressions are like a person’s signature. We are hardly ever rejected, because you can slip the ink pad under a shirt or blouse.”

And so it goes—all a little whacky, but designed with the calculator-quick mind of a master showman. Other pop artists have tended to avoid high society, but Warhol has plunged into party going with gusto; confusing, mystifying, and enthralling everybody. After talking with him at a dinner party not long ago—a conversation in which she chatted on and one and he said almost nothing—Mrs. William Woodward was overwhelmed. “He’s so deep!” she exclaimed, “so deep!” And crazy like a fox.

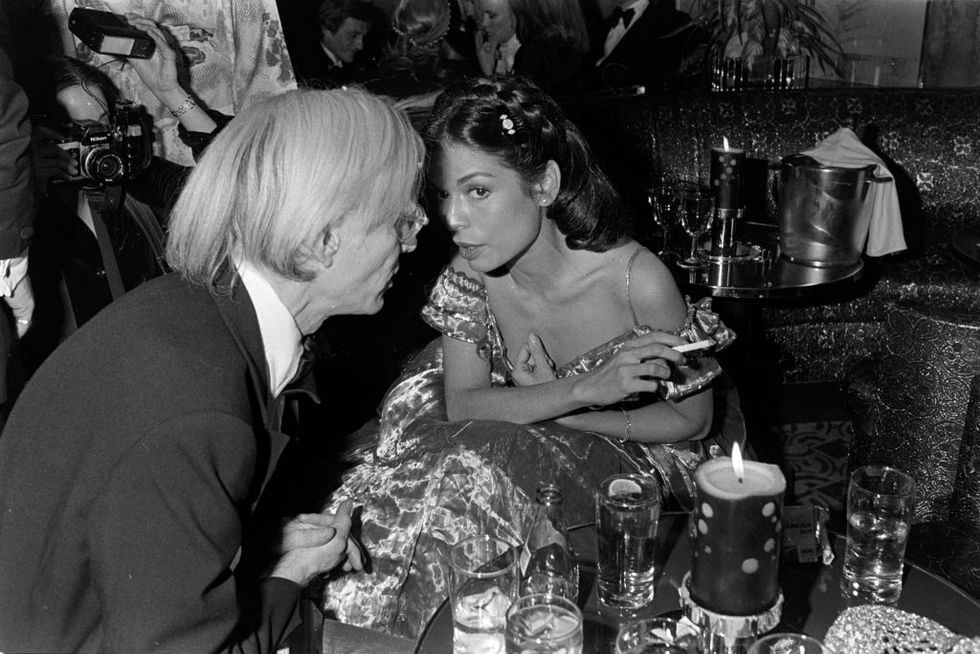

Typically, Warhol says he doesn’t care for social life, hardly ever goes out. “He goes out all the time,” says a friend. “He loves parties. He’s fascinated by rich people, by celebrities, anybody famous. He has an absolute thing about movie stars. When he comes to a party, the firs thing he says is ‘Are there any movie stars here?’” On a recent trip to Mexico he was asked whom he would most like to meet. His list was simple: “Just two—Dolores Del Rio, and the President.” He was disappointed. Miss Del Rio was in California, and the President wouldn’t receive him because of his reputation for dealing, in his films, with drugs and kinky sex. The President pronounced Andy and his friends “trash.” In Mexico City, he was met by a chauffeur-driven limousine (“Andy loves all that sort of thing,” says a friend) and driven to the famous Aztec pyramids outside the city. When the group got to the pyramids, Andy said that he was staying in the car. “Don’t you want to see the pyramids?” a friend asked. “They’re just a pile of rocks,” he said, implying that with enough rocks he could make the same thing.

Though Andy Warhol goes out a lot, he almost never entertains. He keeps an apartment on Lexington Avenue in the Eighties, which he describes as “just a dump” and which he says he likes because something called “The Fertility Institute” is next door. (No such institute is listed in the telephone book.) (Few of the friends and retinue who surround him have ever been inside. Because his films have dealt with homosexuality, lesbianism, rape, violence, nudity, and drugs, it is often supposed that the private life of Andy Warhol, a bachelor, is one of prolonged orgiastic license. Actually, it isn’t.

“Andy’s never tried drugs of any kind,” says a close friend. “He’s never even smoked grass, though on occasion I’ve seen him with other people who were smoking grass. If he has more than a half an ounce of vodka a month, that’s a lot for him.” His personal sex life he has deliberately kept a mystery—part of the smoke screen, part of the mask; because, of course, everybody speculates about it. This same close friend insists that it is quietly chaste and celibate. He is a devout Catholic, as, interestingly enough, are most of his entourage. He is known to be devoted to his mother, but she, too, is carefully protected. This is supposedly because, a couple of years ago, a writer from Esquire got to his mother and wrote about piece about her which was mocking, and which hurt her.

The present headquarters of the Andy Warhol Factory are, despite the raffish image, surprisingly elegant and ordered: typewriters click, business machines whir, telephones ring and are answered by trim and efficient secretaries. The only ominous note—a reminder of the shooting incident—is a sign on the locked front door which reads: KNOCK LOUDLY AND IDENTIFY YOURSELF. Inside, the offices are spacious, high ceilinged, and sunny; furnished with Art Deco display cases which Warhol purchased in Paris, French tapestry chairs and sofas, and a vast desk and sideboard acquired from the first-class salon of the Normandie. Walls are mirrored, desktops are clean and polished. These might be the offices of a rather spiffy stockbroker. They are, of course, a few recherche touches, such as the large stuffed German shepherd (“I was told it used to be Cecil B. DeMille’s dog,” Andy explains) by the front entrance, the framed baby-faced portrait of Shirley Temple, and the visitors who stream in and out.

Andy Warhol’s friends and superstars are always popping by, many of them in bizarre outfits and several of them frank transvestites, including Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn. Joe Dallesandro and his pretty wife are often at The Factory, along with their baby, Joe Jr.—“Our newest superstar.” (Joe Jr. was used in two Warhol feature films, Flesh and Trash.) But otherwise, as a Warhol associate puts it, “It’s all work here.” The Factory opens punctually at nine, breaks for lunch, closes at five. Warhol, his friends say, is an absolute nut on orderliness, so paints, films, and videotapes are all carefully boxed, labeled, cross-indexed, and filed in what The Factor rather grandly calls “Our archives.”

Andy Warhol received another barrage of publicity recently through the controversial television series An American Family, in which the real-life campy son of the family, Lance Loud, goes to New York to join the world of his idol, Mr. Warhol. An American Family is supposed to be straight television reportage, but Andy Warhol claims never to have met, or laid eyes on, anyone named Lance Loud; nor has anyone else in the Warhol set. In one episode of the series, Lance Loud tells his mother that he’s going to Europe under the sponsorship of Robert Scull, the wealthy pop-art collector and one of the first people to buy Warhol oeuvres. Mr. Scull, however, also insists that he has never met Lance Loud and has never sponsored anyone on trips to Europe, indicating that at least part of An American Family may be sheer fiction. Warhol, meanwhile, has no objection to his name being aired frequently on network television.

“The secret of Andy,” says Ethel Scull, “in addition to his fantastic public-relations sense, is that he’s the most incredible voyeur. He loves to sit back and watch people do insidious, dreadful, horrible things.”

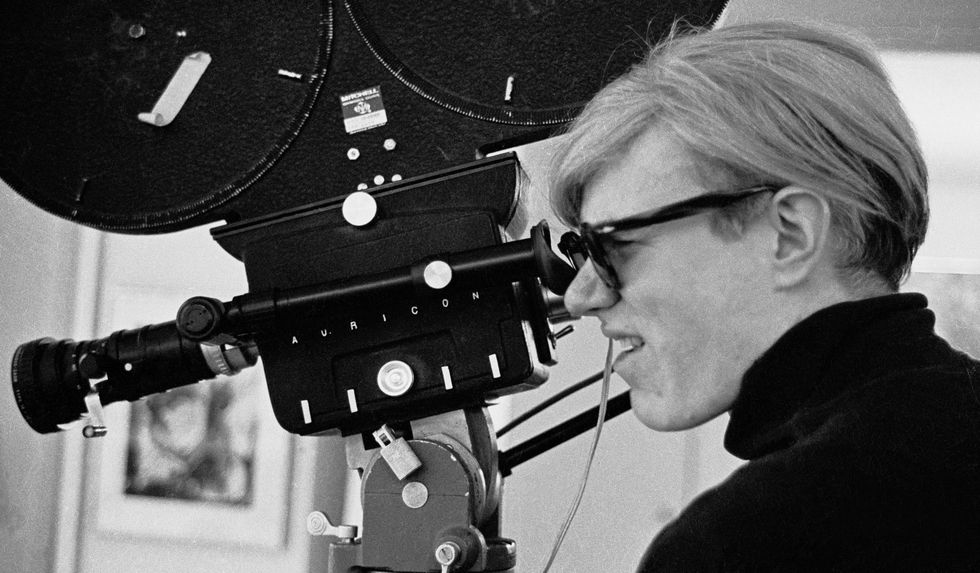

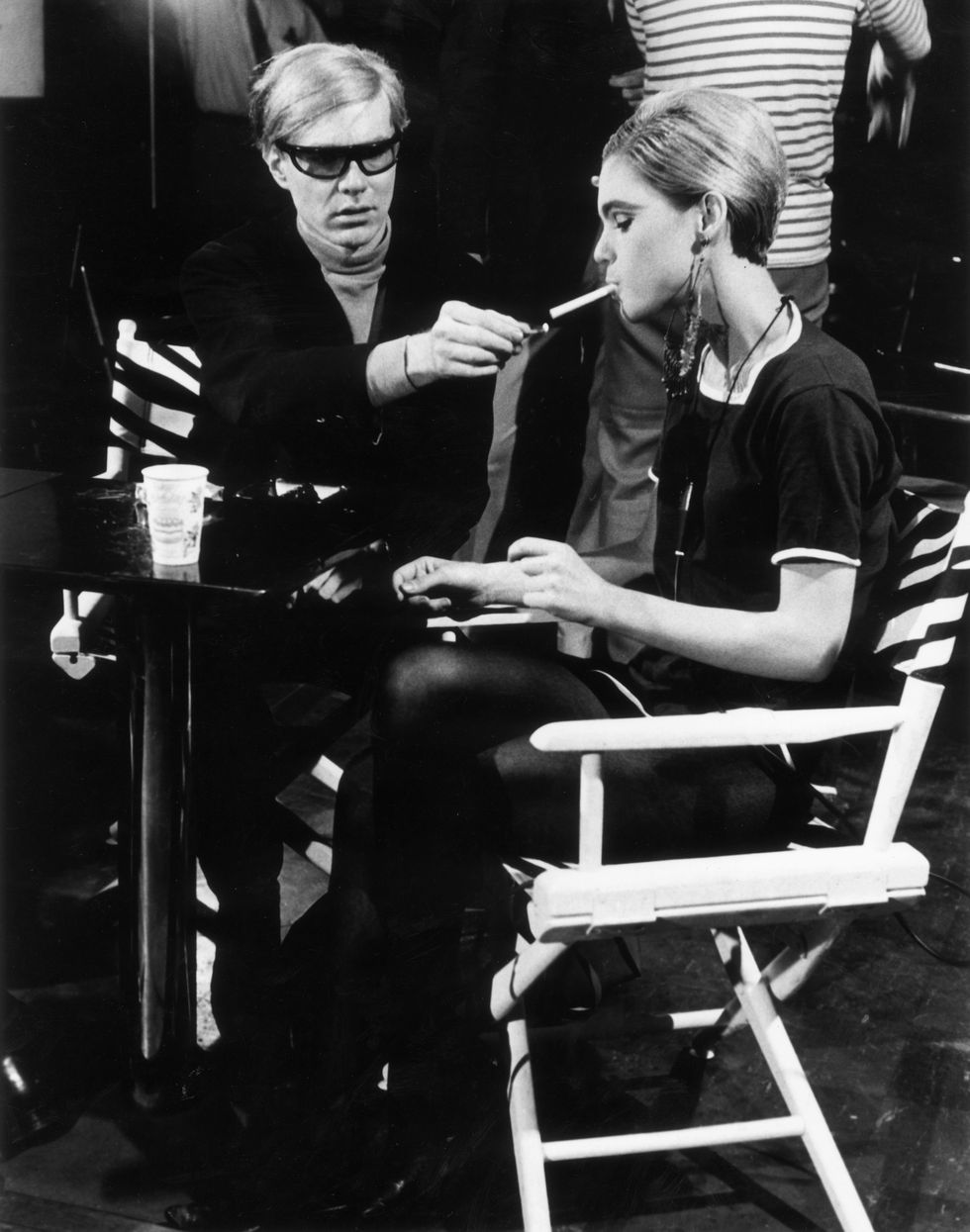

The voyeuristic approach is apparent in his films, which never start out with scripts or even any sort of plan but merely evolve from having his actors get in front of a camera and do or say whatever comes into their heads. He made a film of Mrs. Scull in just this manner. “He sat me down in front of a camera, started it rolling, and walked away,” she says. “It was the most fantastic experience. At first I didn’t know what to do. I smiled, poked at my hair, touched my face. Then I began to relax. Suddenly it was exhilarating, knowing that I could just relax in front of the camera, be myself, express myself in any way I wanted.” Some people become so relaxed in front of the camera that they take off all their clothes. Scull, when she saw the footage of herself, pronounced it “brilliant.” “When my husband saw it, he said there were aspects of my face and personality in the film that he’d never been aware of before,” she says.

The Sculls are credited with discovering Andy Warhol, but actually he was brought to their attention by Henry Geldzahier, the plump panjandrum of the New York art scene. The Sculls visited Warhol’s studio, where he told them he needed $1,400. For $1,400, he told them, they could have whatever they wanted. They took a Campbell’s soup can, a painting of a dollar bill, and three or four other small things.

Because the Sculls are rich and social, entertain a lot, and already had a reputation for buying the most avant of the avant-garde in painting and sculpture, Warhol’s name quickly achieved a certain local celebrity. Ethel Scull then asked Warhol to do her portrait. His approach to this assignment was, on the surface, equally casual and haphazard, but with a designing shrewdness, showing underneath. He would, he told her, have her photographed and then have the photographs reproduced in silk screen process on canvas. To do this, he took her to a Times Square penny arcade (“I’d been hoping for maybe Richard Avedon,” she says) and, armed with lots of quarters, took more than a hundred shots of her in different poses before a do-it-yourself camera.

Months went by and she heard nothing more about the portrait, though a friend told her, “Your pictures are scattered all over Andy Warhol’s floor.” Then one day Mrs. Scull telephoned Warhol and mentioned that her apartment was about to be photographed by Vogue. The next day, Warhol was at her doorstep with the portrait—actually, 32 different portraits which, Warhol said, could be put together and framed “any way you want to.” The result (which was on the Sculls’ wall in plenty of time for Vogue) was called by none other than the late James Rorimer, of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, “the greatest portrait I’ve seen in a hundred years.” It will soon hang in the Met itself.

Andy Warhol himself says that he got the basic idea for his films and portraits from watching late-night television talk shows. As usual, he is sort of telling the truth and sort of not. When his actors romp around happily in front of a motion-picture of still camera, in or out of the nude, using four-letter words, there is an element of Johnny Carson and his reasonably celebrated guests, all furiously winging their way through an unrehearsed hour and a half, each trying to upstate the other, showing off for the camera, and sometimes making fools of themselves.

Right now, one of Warhol’s projects is a series he hopes to sell to television, which will be “sort of a combination soap opera and talk show,” whatever that means exactly. He is also currently making his first 35-millimeter movie with Carlo Ponti, to be called either Flesh for Frankenstein or Frankenstein’s Blood, he hasn’t decided which. “It will be sort of an updated Frankenstein story,” he explains, “with some Dracula thrown in, I think.” The film will be in 3-D (“You have to wear funny glasses to see it, I guess.”) and will star Joe Dallesandro, Monique Van Vooren, “and some young Yugoslavian actor—I forget his name.” Warhol says, “Yeah, I guess we’re going to have to do some sort of script to satisfy Ponti. Somebody can knock something out. But when we start shooting, we’ll probably just ignore the whole thing. To me, acting is just people getting up in front of a camera, doing their own thing, letting whatever hangs out hang out.” The somebody-can-knock-it-out technique was apparent in a recent Vogue article that was published under Andy Warhol’s signature and purported to tell what was on Warhol’s mind. Actually, his various friends and assistants wrote the article in scraps and pieces, pasted it together, and Warhol went over the whole things, scratching out a deletion or adding a sentence here and there.

The voyeuristic approach to his subject matter is, of course, a basically hostile and contemptuous one. But Warhol as a voyeur is not ordinarily our friendly neighborhood voyeur. In real life we can have him arrested. In art, he jars and shocks us but gets away with it. The Warhol contempt for his subjects is visible in his portraits—Marilyn Monroe made to look garishly vapid and tragically worn by life, Jacqueline Kennedy, silk-screened from the photograph of her blank and dumb-struck face at the swearing-in ceremony in Dallas after the assassination. His recent series of pictures of electric chairs, silkscreened in ghastly colors, comprises a devastating and disturbing attack on the American Establishment. “The man is clearly an enemy of the people,” wrote a London critic after his 1971 exhibition at the Tate Gallery. “The static camera recording his zany actors, the silkscreen processing from which he finally divorced himself, leaving the process of production to assistants, remind us that he is the archetypical exploiter, whose work drip with the surplus value of the hired labor he has employed. Warhol is not just a reflection of the system; he is a functional microcosm of it.” Several of Warhol’s friends agree that he is, indeed, contemptuous of the system, and they attribute this to his early frustrations as an artist.

Warhol dislikes talking about his early years. And typical of his fondness for confusing and clouding issues, he lists his birthplace in Who’s Who as Cleveland. Actually he was born and raised in Pittsburgh, where he attended Carnegie Tech. He came to New York via Philadelphia, where he started out as a commercial artist and managed to get to know the millionaire art patron Henry McIlhenny. He was first noticed in the commercial art world for a series of ads her produced for I. Miller shoes. I. Miller, his friends feel, used and exploited Warhol, kept him underpaid and under-recognized despite the fact that his I. Miller work succeeded in imparting a grace and elegance and beauty to the shoes. Since the I. Miller days, his work has represented a nose-thumbing at American art, commerce, and society.

But Warhol’s friend Bob Colaciello, who helps, along with such Warhol regulars as Paul Morrissey and Fred Hughes, to put out Warhol’s new venture, a monthly newspaper-magazine, called Interview (very Talk-Show-y in format, already with a circulation of nearly 60,000) says “Andy is a kind of mirror—a kind of prophetic mirror. He’s always years ahead of everybody else. Audiences were shocked by Chelsea Girls when it was released in 19665. But by 1968, when I was in college, every college in the country was like Chelsea Girls—the drugs, the sex, everything Andy prophesized. Also, he’s a genius because he refuses to discriminate. Everything that’s going on to him, is worth watching, photographing recording, taking down.”

Andy Warhol’s voyeurism is also the clear key to his current social success which he so obviously relishes. Because in social situations he says almost nothing, contributes nothing but his physical presence. He is the perpetual listener, observer, cameraman, and audience. His friends in New York and European society thereby become performers in a Warhol movie, superstars themselves—a heady feeling. They strip themselves bare in front of him and he merely nods and smiles encouragingly. It’s all a little like unburdening yourself before a soft-spoken shrink who somehow manages to reassure you that the nasty things you’re done all week are the natural expression of wonderful you.

But the trouble with all this is that his friends in society all develop actorish artistic temperaments, like talk-show panelists all vying for more than equal time, for more than their share of space on the screen.

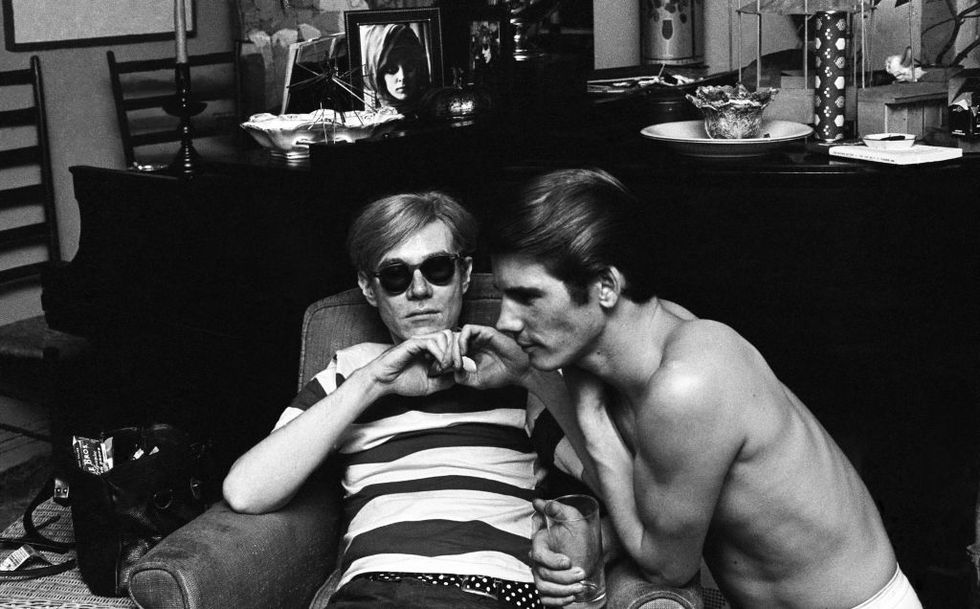

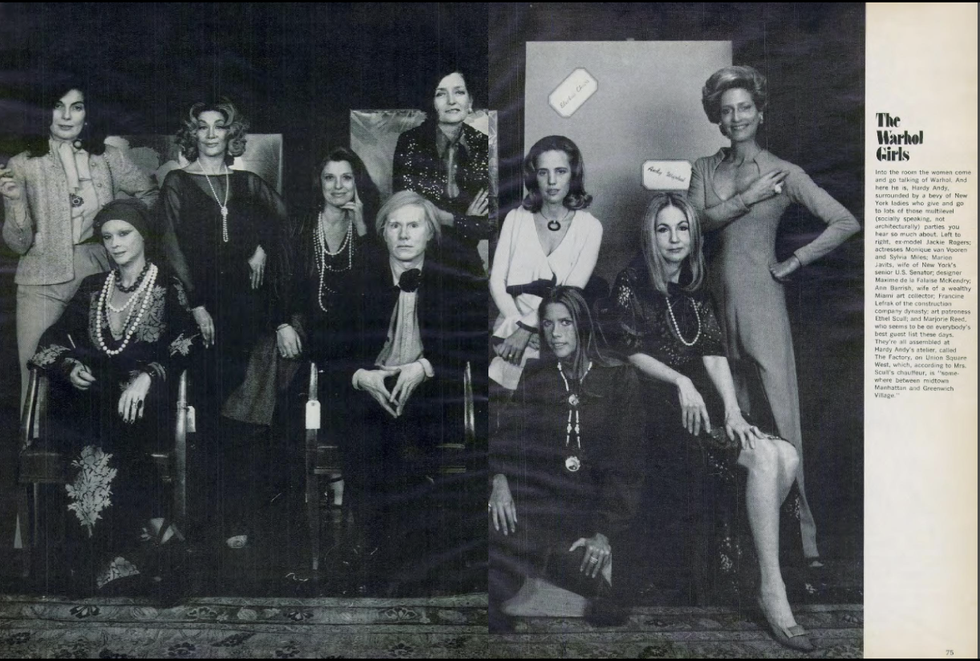

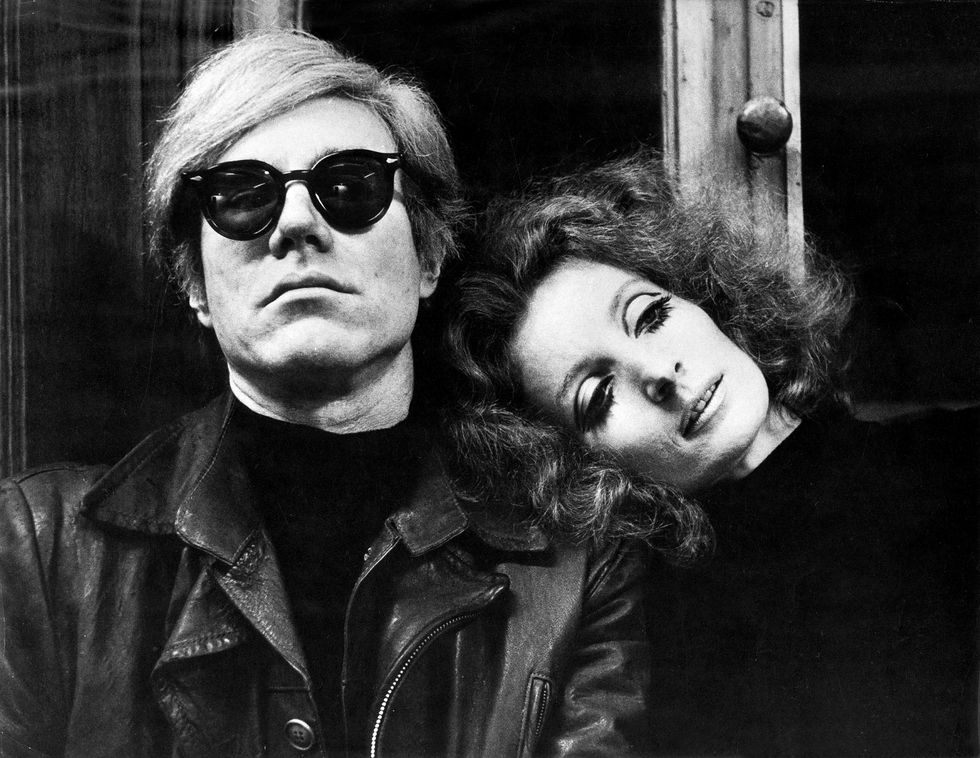

Turn back to the two-page photograph that accompanies this article, in which nine of Andy Warhol’s social friends are posed with their hero, and study it. It was not an easy photograph to take, or an easy group to assemble. A number of his friends refused to pose with others of his friends. Good friend Baby Jane Holzer refused to be in the picture because Marjorie Reed was in it. Marion Javits agreed at first, then changed her mind, then finally agreed with strongly expressed misgivings to join the group. A number of Warhol’s friends refused to be in the same picture with his friend Mrs. Scull, Mrs. Diana Vreeland, former editor of Vogue and a good friend of Warhol’s, first said yes, then said no, because of the others with whom she would have to share the limelight. Gloria Vanderbilt Cooper refused to be in the photograph saying, “He’s been trying for years to do something with me, but I want nothing to do with him. There’s a necrophiliac quality in his work that goes completely against the grain of everything I do and believe in. I don’t want to be associated with him.” And so it went.

The photograph of Andy Warhol and his friends who finally agreed to be photographed with him—and, most important, with each other—have you ever seen such a collective look of unrestrained hostility? Women’s Wear Daily, covering the posing session, described the atmosphere as “like a neighborhood cat fight.” In the middle of it, ever the observer and relisher and recorder of “people doing insidious, dreadful, horrible things,” sits Andy Warhol, serene and poised and attentive. He may be the enemy of the people. But, in the meantime, a great many people are trying—jealously, ferociously, with claw curled and fang bared—to be his Friend.

![Liza Minnelli;Andy Warhol;Halston;Jack Jr. Haley [& Wife];Mrs. Mick Jagger liza minnelliandy warholhalstonjack jr haley mrs mick jagger](https://hips.hearstapps.com/hmg-prod/images/celebrities-during-new-years-eve-party-at-studio-54-halston-news-photo-1690909691.jpg?resize=980:*)