This past weekend, we spent some time among the computer enthusiasts at the Vintage Computer Fest East, hosted by the Mid-Atlantic Retro Computing Hobbyists. The event was a mix of things: part history lesson, part nostalgia trip, and a bit of swap meet thrown in. All in all, it was fascinating to see some of the hardware that had been preserved in working order. In a lot of cases, I was completely unaware that the hardware maker ever existed. In others, there was a certain nostalgia for long-deceased platforms. But the big surprise was probably how people had merged some of the old hardware with modern tech to create some things that were very modern.

The old big iron

One of the first stops was with Ian Primus, who just happened to be maintaining a bit of hardware called the Prime 4450. Although he could have easily fit inside the case, he described it as "one of the small ones." It came with six boards that constituted the 32-bit CPU, and another eight to handle I/O; the case held both a disk and tape drive. It ran (surprise!) the PrimeOS, which was a multi-user operating system that supported virtual memory.

Prime apparently died in part due to a failed merger with a CAD company called Computervision in 1992, but according to Primus, there are a few of the systems still in use. Ian came equipped with terminals to connect in to the Prime, but power issues were keeping him from starting things up on Saturday.

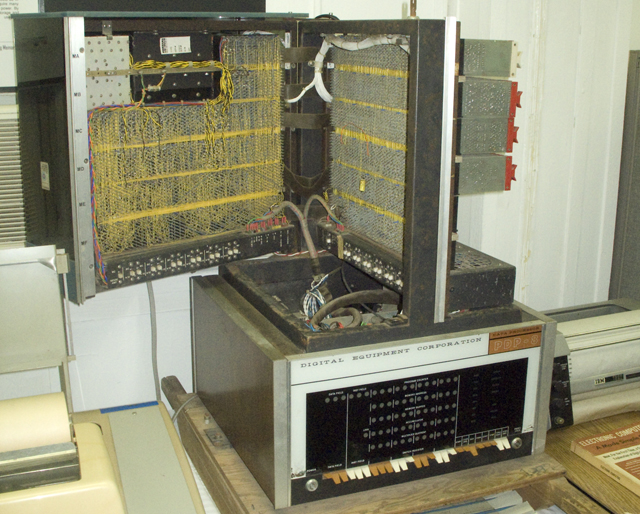

Digital Equipment, which eventually went on to produce the high-performance Alpha chip, was represented at the expo by one of its PDP-series machines, complete with tape drive and a sign warning of high voltage hazards.

A PDP-series machine (a PDP-8, in this case) also made an appearance when we got a tour of some of the hardware on display in the permanent Vintage Computer Museum housed at Info Age, led by March's Christian Liendo. In this case, it's a work in progress; the machine was found in a barn, and Liendo pointed out that you could still see a spot where a mouse had built a bit of a nest in the hardware.

MARCH doesn't really have much in the way of a budget to buy the hardware it puts on display, but every now and again someone gets in touch because they've heard about the group and would like to offer some unused equipment to them. (MARCH received at least two computers on Saturday, as well.) Once on hand, the group can usually find someone willing to try to get it working again—usually someone who had used the same hardware during their working years.

Also on display was this beast from a company that I'd forgotten once made computers, Perkin-Elmer.

Perkin-Elmer had a significant position in scientific instrumentation, and purchased a computer manufacturer, in keeping with scientists' increasing reliance on big, multiuser systems back in the 1970s and 80s. As the scientific computing shifted to desktops, the company dropped out. By the time I was in graduate school in the early 1990s, Perkin-Elmer's claim to fame was the hardware needed to run DNA amplification reactions, but it had been a significant force less than a decade earlier.

Old dogs, new tricks

A lot of the attendees did their best to keep old hardware relevant, but Ralph Dodd might have had the most impressive collection of repurposed equipment. Pictured below is his hacked Kaypro, an early "portable" computer. He got the case in great condition, but couldn't resuscitate the internals. So he replaced them. The Kaypro case is now home to an Atari motherboard and a monochrome display that sat unused for years.

The boot system for the hardware is pretty unusual, as well. With the help of a special adaptor cable, the Atari's disk interface plugs into a laptop; on the laptop end, software allows Dodd to select the specific software it boots with. That wasn't the only thing he was doing with Atari hardware. He had a classic gaming console, and had hacked one of its cartridges to hold an excessively large ROM. As a result, each cartridge could hold 64 games—flicking a few toggle switches at the end of the cartridge determined which of the games launched when the console started up.

But the star of the show may have been the Commodore 64, the one bit of hardware there I have actually personally owned. There were a couple of C64s on display, but the most impressive was one run by an individual whose name I missed. Feeling constrained by his dual-floppy drives, he'd hooked up an adaptor that had it reading from compact flash cards. Amazingly, the file system could apparently handle at least 4GB of storage (he hadn't tried to go higher yet).

But his C64 was also sporting a hardware/software combination that he'd picked called Shredz64. The hardware hooks the C64 up to a guitar controller, while the software turns it into an eight-bit guitar hero. It consistently drew a crowd.

reader comments

56