By Steve Miller

The term "Landscape Photography" isn't used much in the underwater photography jargon. This comes as a surprise considering how popular it is topside, but there are good reasons for this.

Most scuba divers begin by shooting images of fish - portraits if you prefer. Whether shooting the smallest nudibranch or a whale shark, the technique typically starts with trying to get close enough to fill the frame with your subject. Then you work on composing the scene with your camera angle, lighting, and background (to the extent that you are able, which is often not much due to uncooperative subjects). These variables can be combined and tweaked in endless iterations.

Visibility underwater never approaches what we see in air, even on misty mornings. © 2022 Steve Miller

But what about the vistas? The huge, sweeping panoramic views of the reef? Images that carry the viewer into the frame as their eye wanders the scene with elements that are close and also very far away? These perspectives that are ubiquitous topside seem to have most underwater photographers seeing blue.

The Problem

The landscape photographer should have an advantage underwater. We can fly for one thing, so camera angles are flexible. We don’t have to wait and hope for cooperative marine life. And unless you want to color up something in the foreground, there is no need for lighting. So why do most of my underwater landscapes look flat, grainy, and blue when I'm using similar lens lengths to my topside work?

A lush coral reef, with amazing visibility can be like walking through a meadow of wildflowers; lots of colors, textures, and detail. But one big difference: the clearest reef you may ever swim has very limited visibility. It's like a thick fog has come in and reduced the visibility to 100 feet (30 meters) or less. The detail goes away, as does the color and the contrast.

The reduced visibility from this controlled burn is better than many dive sites. © 2022 Steve Miller

Solutions!

To shoot a good landscape image underwater we need to force the perspective of the lens to capture a relatively small area in a way that makes it look larger and encompasses the basic rules of composition. On the surface you may be located miles away from the feature you're shooting. Underwater you're limited to features 100 foot away - at the very most if you’re lucky enough to have that kind of visibility - and closer.

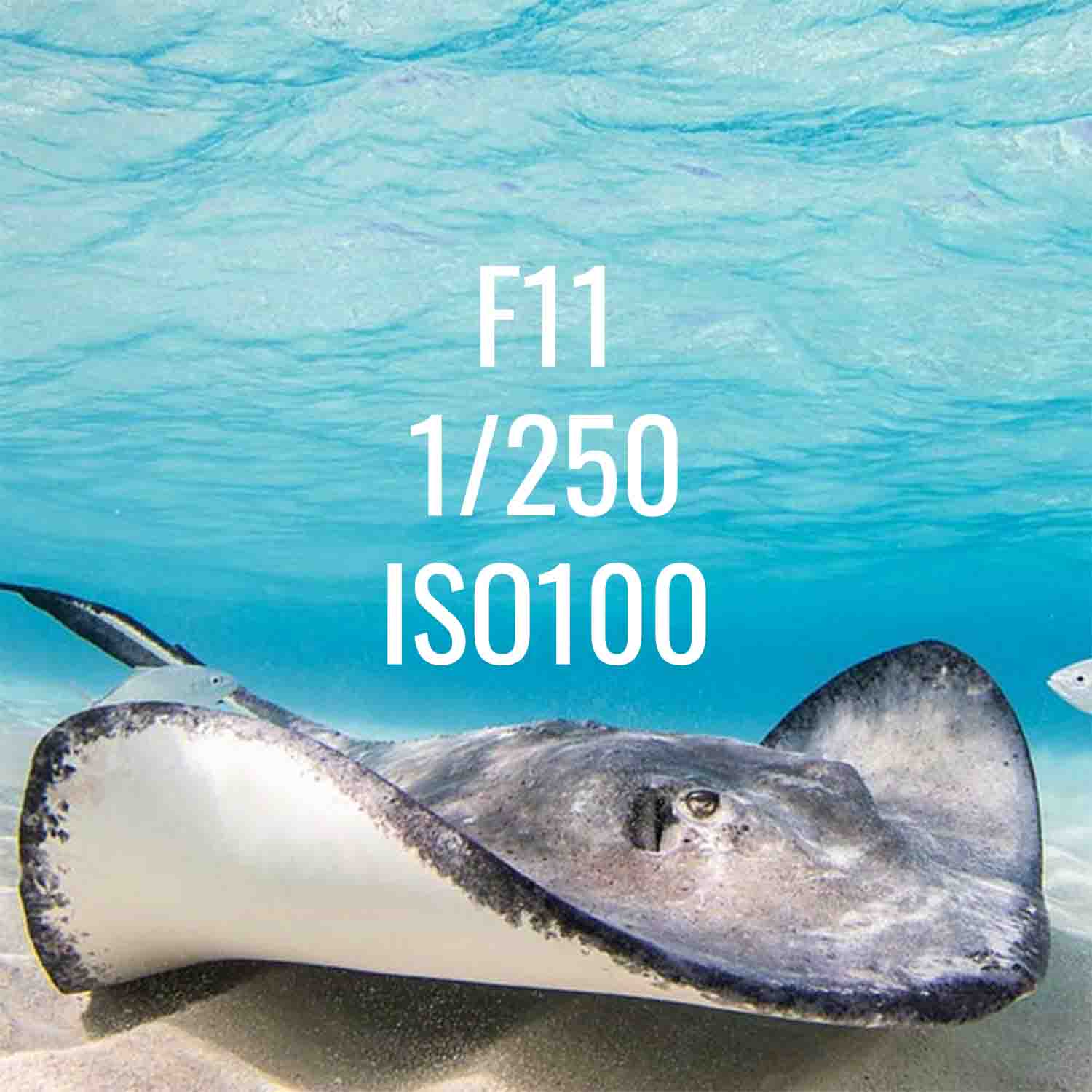

The shallowest reef with 100ft. of visibility is as good as it gets for color in natural light. © 2022 Steve Miller

Your first thought may be to shoot what you are looking at straight on, but this won’t work for the lens. Optics are quite a bit different underwater, and the lens doesn’t perceive the way your eye does. With a super wide angle or fisheye lens, the smallest tilt of the camera will warp the shapes and shift spacial relationships between the objects that make up your image.

There are actually formulae that landscape painters have used for a balanced, pleasing outdoor scene. Still photographers can borrow some of these “rules of composition” to great advantage. It is always smart to look for repeating patterns, leading lines, curves, and circles that are vaguely in your vista. These shapes exist on the reef, but you have to coax them sometimes. Instead of trying to capture the entire expanse of the scene, try to find a small section of reef that will fit into your field of view with elements close and far that relate to each other in an artistic way.

When we flash something close like this sponge it is close-focus wide-angle, probably the most popular wide angle technique. Treat your background like a Landscape image with an upward camera angle. © 2022 Steve Miller

There's Still Work to be Done...

Ok so you've chosen a section of the dive site to focus on. Before you start looking for flattering camera angles, ask yourself what made you choose this particular section. The answer should be lighting. And more specifically contrast. The enemy of underwater landscapes is actually the water, and the softness created by shooting through it at some distance. You need broken light, hard landscape frames, and solid objects interrupting the light rays to create contrast. Don't be afraid of having the sun ball in the frame, though the sun may light the landscape in a more pleasing way when it's behind you.

Without flash we have no color and rely on light and shadow and shape for interest. © 2022 Steve Miller

We generally accept that strobe light only travels a few feet underwater. This is true, but only to the extent that the light you are capturing has been filtered (and colored) by the water. Two strong strobes can create highlights and fill shadows from great distances, depending on the visibility.

How far can a flash go? If you use long strobe arms and stretch them out to the sides as far as they reach, you can light a large section of reef. Boosting saturation in the edit can find colors at surprising distances. © 2022 Steve Miller

Post-Production

Underwater landscape images my take a bit more work in the edit. Expect to increase contrast, clarity, and sharpness. Use brushes in Lightroom or Photoshop to accentuate the tonal range.

If you tire of all the blue, try converting the image to black and white, adjusting the tint with the white balance slider, or even desaturating the whole scene.

The strobes are too far away in this scene to create true colors, but they create highlights. © 2022 Steve Miller

Conclusion

So why aren't landscape images more popular with underwater shooters? Probably because most of us prefer the close focus wide angle (CFWA) technique, and treat the composition like a landscape with an exception. Something is placed very close to the lens and usually colored up with flash. In a properly composed image, the combination of a landscape background with a brightly colored foreground subject blends both techniques nicely for us.

Freshwater springs and cenotes offer visibility and contrast. © 2022 Steve Miller

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Additional Reading

Close Focus Wide Angle In Depth

Why You Need a Fisheye Lens Underwater

How to Shoot Split Shots (Half-In, Half-Out of the Water)

Black and White Conversion for Underwater Photography

When to Change Aperture Undewater

Streaming Light Rays Underwater Camera Settings

Tiny Scenes | Building an Underwater Still Life in Miniature

![What I Wish I Knew When I Started in Underwater Photography [VIDEO]](http://www.ikelite.com/cdn/shop/articles/what-i-wish-i-knew_10872ac2-9104-4942-a4cf-eda88d0fcb39.jpg?v=1643998370&width=2001)