Campus Martius Antiquae Urbis.

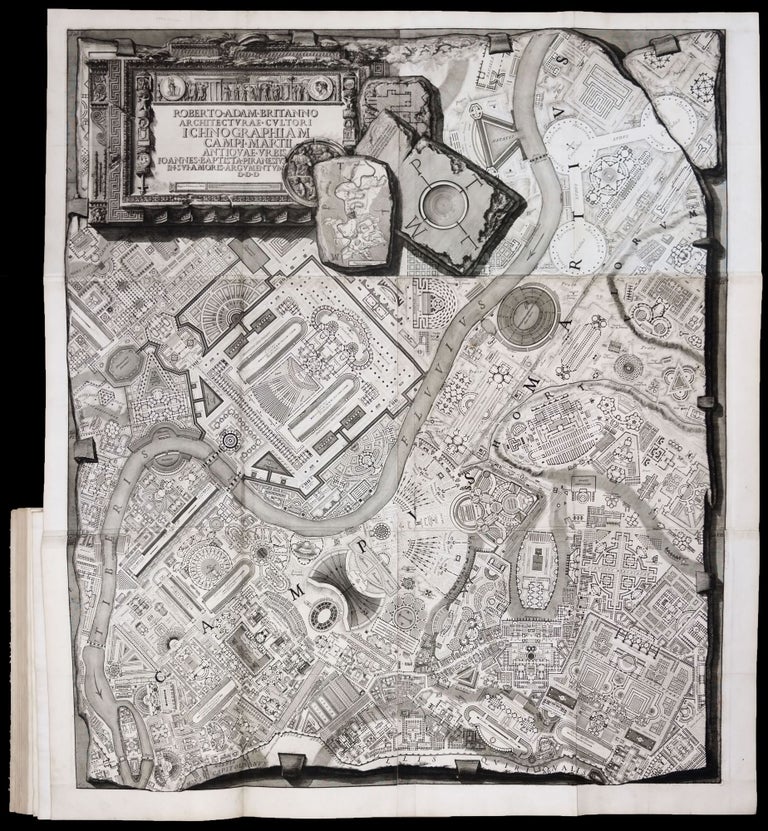

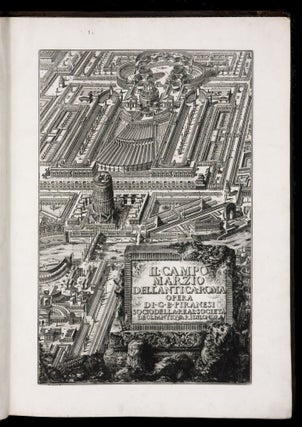

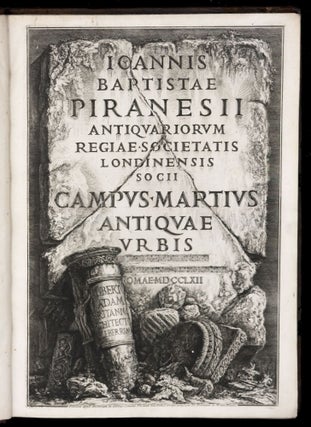

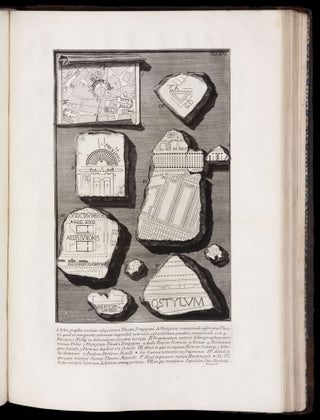

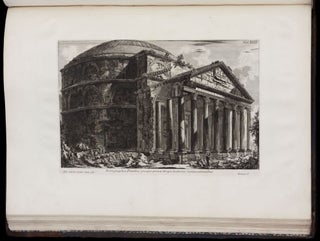

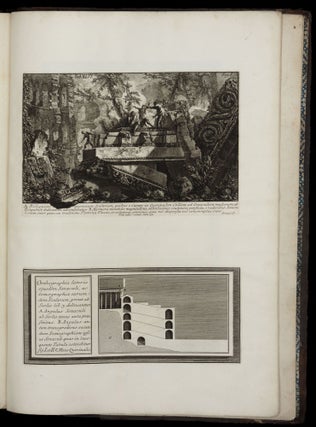

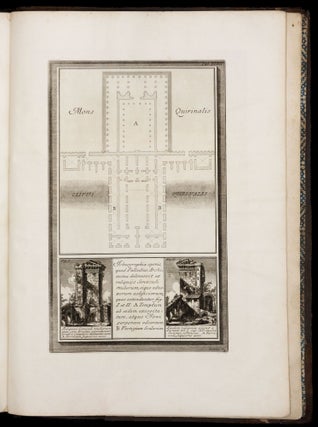

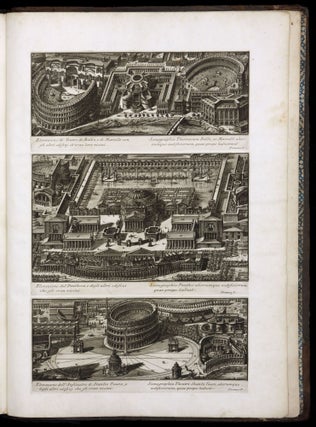

Large folio [55.0 x 39.2 cm]. (1) f. etched/engraved Latin title page, (1) f. etched Italian title page, (4) ff. letterpress dedication with (2) large etched headpieces, 69 pp. letterpress text with (2) large etched initials and (2) large etched tailpieces, (1) p. blank verso, XII pp. letterpress Latin and Italian ‘indexes’ (keys) to plates III and IV, xvii pp. letterpress Latin and Italian ‘catalogues’ to the folding plan, and with (52) etched/engraved coppers on XLVIII consecutively numbered plates (2 folding, 1 double page), mainly by Piranesi, including the 6 sheet map (joined) comprising plates numbered V-X. Bound in contemporary calf, spine elaborately gilt, morocco lettering piece laid to spine, gold-tooled borders and edges to upper and lower covers, block-printed endpapers. Minor rubbing and edge wear to spine and boards, head- and tail-bands renewed. Occasional minor toning, the occasional minor stain, a few short separations at the folds of the large plan. First edition – and fine copy – of Piranesi’s incomparable reconstruction of Rome’s Campus Martius, a work famed for its archaeological ambition, its graphic inventiveness, and as a sourcebook for the architectural imagination which continues to influence architectural theorists and practitioners today. “An exceptional personality, Piranesi transfigured his personal failure as an architect by re-creating ancient Roman architecture and urbanism through a richly complex representation” (Millard, Italian, p. 297). In the Campus Martius Piranesi illustrates the region’s topography, discusses its archeology, and provides theatrical views of surviving monuments (e.g., Tiber Island, Porticus Octaviae, Mausoleum of Augustus, the Pantheon, Theater of Marcellus, Mausoleum of Hadrian, etc.), but the most arresting feature of the work is Piranesi’s most ambitious cartographic effort, the Ichnographia, a 6-sheet fantastic reconstruction of the Campus Martius in plan, measuring 1.35 x 1.17 meters. In the Ichnographia and in the work’s other ideal imaginings of Rome’s ancient urban environment (e.g., plate LXVIII and the Italian title page), Piranesi overcomes the limitations of practical architecture, building his visions on paper instead of in stone: “The map is the quintessential product of an architect, and it privileges buildings above all else” (J. Maier, p. 13). The Campus Martius, in fact, marked the culmination of the friendship between Piranesi and the great Scottish architect Robert Adam (1754-98), the work’s dedicatee (see below), making it of Grand Tour and British interest and an important source for the active architectural interpretation of ancient Rome far from the Eternal City itself. The contents of the work are well described by M. Pollak (in Millard, Italian), from which we may excerpt as follows: “The publication borrows from the two main interests of the author, the archaeological research and the polemical battles of the early 1760s. His historical inquiry is here committed to supporting his view of the primacy of Roman builders … [The] plan is one of Piranesi’s most feverish fantasies, marshalling a huge range of imaginary constructs for the celebration of ancient Rome. Within this plan he proposes an urban and architectural landscape of the utmost complexity. Piranesi achieves this tour de force through a great variety of illustrations and employs every means of representation at his disposal. “In this work, Piranesi refined his method of graphic juxtaposition. The Campo Marzio opens with a great plan of Rome with stone fragments illusionistically ‘placed’ on it; subsequently sheets of details are ‘pinned’ onto larger plans and views. Thus Piranesi uses trompe l’oeil to juxtapose differently scaled drawings … He practices, throughout, an X-ray vision that enables him to locate the extant fragments of ancient ruins within existing buildings, such as the church of Santa Maria in Via Lata. He is no longer merely illustrating but re-creating a lost world … His innovation, then, as Wilton-Ely has summarized, is to show the ruins as a view rather than merely offering a dry archaeological reconstruction” (Pollak, Millard Italian, pp. 312-13). Piranesi’s earlier works on the antiquities of ancient Rome (Antichita romane, 1756-7) ran into difficulties with its dedicatee, Lord Charlemont. For his new volume, Piranesi required a new patron. “The Campus Martius owes its existence as a separate volume of the Antichita romane to the vanity of the young Scots architect Robert Adam,” notes Joseph Connors in his recent monograph on the work (p. 36). Adam had come to admire Piranesi during his stay in Rome (1755-57) and accepted the latter’s offer knowing it would entail the purchase of some 100 copies for resale in England and Scotland. However, in exchange Adam insisted that Piranesi publish the Campus Martius as a stand-alone study, divorced from the Antichita romane which had borne the name of Charlemont. Adam’s name thus features prominently on the title page of the present work, where Piranesi also proudly flaunts his own membership in the Royal Society of London. A medallion on the right of the large folding plate also shows the two friends in profile, in the fashion of duumviri. (Adam’s name also appears in the dedication of the 6-sheet map.) Piranesi never abandoned his architectural ambitions, and in 1764-66 the Chiesa di Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine in Rome was remodeled according to his designs. He also designed the fanciful square in front of the church, the Piazza dei Cavaliere di Malta. These constituted Piranesi’s only built works. Piranesi broke the boundaries of etching and engraving through his acts of improvisation during the printing process, especially in the variable applications of ink in different areas of the copperplate. This results in a perhaps unprecedented amount of creative variation among copies, in which the exigencies of the printing process enter into the creative act as never before in the graphic arts. The present example of the Campus Martius is distinguished by its excellent preservation and fine strikes throughout. * Millard, Italian, no. 91; J. Connors, Piranesi and the Campus Martius: The Missing Corso: Topography and Archaeology in Eighteenth-Century Rome; M. Bevilacqua, Roma nel secolo dei lumi. Architettura, erudizione, scienza nella pianta di G. B. Nolli ‘celebre geometra’; M. Bevilacqua, ed., Nolli, Vasi, Piranesi: immagine di Roma antica e moderna Rappresentare e conoscere la metropoli dei lumi; M. Tafuri, The Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant-Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s; J. Wilton-Ely, “Utopia or Megalopolis? The ‘Ichnographia’ of Piranesi’s Campus Martius Reconsidered,” in A. Bettagno, ed., Piranesi tra Venezia e l’Europa, pp. 293-304; J. Maier, “Rome Lost and Found: A Review of Piranesi and the Campus Martius: The Missing Corso – Topography and Archaeology in Eighteenth-Century Rome,” Architectural Histories, 1(1) (2013), p. 13.

Price: $0.00